Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Political Thought in the American Colonies

American political ideas regarding liberty and self-government did not suddenly emerge full-blown at the moment the colonists declared their independence from Britain. The varied strands of what became the American republic had many roots, reaching far back in time and across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe. Indeed, it was not new ideas but old ones that led the colonists to revolt and form a new nation.

The beliefs and attitudes that led to the call for independence had long been an important part of colonial life. Of all the political thinkers who influenced American beliefs about government, the most important is surely John Locke (Figure 2.2). The most significant contributions of Locke, a seventeenth-century English philosopher, were his ideas regarding the relationship between government and natural rights, which were believed to be God-given rights to life, liberty, and property.

Locke was not the first Englishman to suggest that people had rights. The British government had recognized its duty to protect the lives, liberties, and property of English citizens long before the settling of its North American colonies. In 1215, King John signed Magna Carta—a promise to his subjects that he and future monarchs would refrain from certain actions that harmed, or had the potential to harm, the people of England. Prominent in Magna Carta’s many provisions are protections for life, liberty, and property. For example, one of the document’s most famous clauses promises, “No freemen shall be taken, imprisoned . . . or in any way destroyed . . . except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” Although it took a long time for modern ideas regarding due process to form, this clause lays the foundation for the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. While Magna Carta was intended to grant protections only to the English barons who were in revolt against King John in 1215, by the time of the American Revolution, English subjects, both in England and in North America, had come to regard the document as a cornerstone of liberty for men of all stations—a right that had been recognized by King John I in 1215, but the people had actually possessed long before then.

The rights protected by Magna Carta had been granted by the king, and, in theory, a future king or queen could take them away. The natural rights Locke described, however, had been granted by God and thus could never be abolished by human beings, even royal ones, or by the institutions they created.

So committed were the British to the protection of these natural rights that when the royal Stuart dynasty began to intrude upon them in the seventeenth century, Parliament removed King James II, already disliked because he was Roman Catholic, in the Glorious Revolution and invited his Protestant daughter and her husband to rule the nation. Before offering the throne to William and Mary, however, Parliament passed the English Bill of Rights in 1689. A bill of rights is a list of the liberties and protections possessed by a nation’s citizens. The English Bill of Rights, heavily influenced by Locke’s ideas, enumerated the rights of English citizens and explicitly guaranteed rights to life, liberty, and property. This document would profoundly influence the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.

American colonists also shared Locke’s concept of property rights. According to Locke, anyone who invested labor in the commons—the land, forests, water, animals, and other parts of nature that were free for the taking—might take as much of these as needed, by cutting trees, for example, or building a fence around a field. The only restriction was that no one could take so much that others were deprived of their right to take from the commons as well. In the colonists’ eyes, all free white males should have the right to acquire property, and once it had been acquired, government had the duty to protect it. (The rights of women remained greatly limited for many more years.)

Perhaps the most important of Locke’s ideas that influenced the British settlers of North America were those regarding the origins and purpose of government. Most Europeans of the time believed the institution of monarchy had been created by God, and kings and queens had been divinely appointed to rule. Locke, however, theorized that human beings, not God, had created government. People sacrificed a small portion of their freedom and consented to be ruled in exchange for the government’s protection of their lives, liberty, and property. Locke called this implicit agreement between a people and their government the social contract. Should government deprive people of their rights by abusing the power given to it, the contract was broken and the people were no longer bound by its terms. The people could thus withdraw their consent to obey and form another government for their protection.

The belief that government should not deprive people of their liberties and should be restricted in its power over citizens’ lives was an important factor in the controversial decision by the American colonies to declare independence from England in 1776. For Locke, withdrawing consent to be ruled by an established government and forming a new one meant replacing one monarch with another. For those colonists intent on rebelling, however, it meant establishing a new nation and creating a new government, one that would be greatly limited in the power it could exercise over the people.

The desire to limit the power of government is closely related to the belief that people should govern themselves. This core tenet of American political thought was rooted in a variety of traditions. First, the British government did allow for a degree of self-government. Laws were made by Parliament, and property-owning males were allowed to vote for representatives to Parliament. Thus, Americans were accustomed to the idea of representative government from the beginning. For instance, Virginia established its House of Burgesses in 1619. Upon their arrival in North America a year later, the English Separatists who settled the Plymouth Colony, commonly known as the Pilgrims, promptly authored the Mayflower Compact, an agreement to govern themselves according to the laws created by the male voters of the colony.1 By the eighteenth century, all the colonies had established legislatures to which men were elected to make the laws for their fellow colonists. When American colonists felt that this longstanding tradition of representative self-government was threatened by the actions of Parliament and the King, the American Revolution began.

The American Revolution

The American Revolution began when a small and vocal group of colonists became convinced the king and Parliament were abusing them and depriving them of their rights. By 1776, they had been living under the rule of the British government for more than a century, and England had long treated the thirteen colonies with a degree of benign neglect. Each colony had established its own legislature. Taxes imposed by England were low, and property ownership was more widespread than in England. People readily proclaimed their loyalty to the king. For the most part, American colonists were proud to be British citizens and had no desire to form an independent nation.

All this began to change in 1763 when the Seven Years War between Great Britain and France came to an end, and Great Britain gained control of most of the French territory in North America. The colonists had fought on behalf of Britain, and many colonists expected that after the war they would be allowed to settle on land west of the Appalachian Mountains that had been taken from France. However, their hopes were not realized. Hoping to prevent conflict with Indian tribes in the Ohio Valley, Parliament passed the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade the colonists to purchase land or settle west of the Appalachian Mountains.2

To pay its debts from the war and maintain the troops it left behind to protect the colonies, the British government had to take new measures to raise revenue. Among the acts passed by Parliament were laws requiring American colonists to pay British merchants with gold and silver instead of paper currency and a mandate that suspected smugglers be tried in vice-admiralty courts, without jury trials. What angered the colonists most of all, however, was the imposition of direct taxes: taxes imposed on individuals instead of on transactions.

Because the colonists had not consented to direct taxation, their primary objection was that it reduced their status as free men. The right of the people or their representatives to consent to taxation was enshrined in both Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights. Taxes were imposed by the House of Commons, one of the two houses of the British Parliament. The North American colonists, however, were not allowed to elect representatives to that body. In their eyes, taxation by representatives they had not voted for was a denial of their rights. Members of the House of Commons and people living in England had difficulty understanding this argument. All British subjects had to obey the laws passed by Parliament, including the requirement to pay taxes. Those who were not allowed to vote, such as women and blacks, were considered to have virtual representation in the British legislature; representatives elected by those who could vote made laws on behalf of those who could not. Many colonists, however, maintained that anything except direct representation was a violation of their rights as English subjects.

The first such tax to draw the ire of colonists was the Stamp Act, passed in 1765, which required that almost all paper goods, such as diplomas, land deeds, contracts, and newspapers, have revenue stamps placed on them. The outcry was so great that the new tax was quickly withdrawn, but its repeal was soon followed by a series of other tax acts, such as the Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed taxes on many everyday objects such as glass, tea, and paint.

The taxes imposed by the Townshend Acts were as poorly received by the colonists as the Stamp Act had been. The Massachusetts legislature sent a petition to the king asking for relief from the taxes and requested that other colonies join in a boycott of British manufactured goods. British officials threatened to suspend the legislatures of colonies that engaged in a boycott and, in response to a request for help from Boston’s customs collector, sent a warship to the city in 1768. A few months later, British troops arrived, and on the evening of March 5, 1770, an altercation erupted outside the customs house. Shots rang out as the soldiers fired into the crowd (Figure 2.3). Several people were hit; three died immediately. Britain had taxed the colonists without their consent. Now, British soldiers had taken colonists’ lives.

Following this event, later known as the Boston Massacre, resistance to British rule grew, especially in the colony of Massachusetts. In December 1773, a group of Boston men boarded a ship in Boston harbor and threw its cargo of tea, owned by the British East India Company, into the water to protest British policies, including the granting of a monopoly on tea to the British East India Company, which many colonial merchants resented.3 This act of defiance became known as the Boston Tea Party. Today, many who do not agree with the positions of the Democratic or the Republican Party have organized themselves into an oppositional group dubbed the Tea Party (Figure 2.4).

In the early months of 1774, Parliament responded to this latest act of colonial defiance by passing a series of laws called the Coercive Acts, intended to punish Boston for leading resistance to British rule and to restore order in the colonies. These acts virtually abolished town meetings in Massachusetts and otherwise interfered with the colony’s ability to govern itself. This assault on Massachusetts and its economy enraged people throughout the colonies, and delegates from all the colonies except Georgia formed the First Continental Congress to create a unified opposition to Great Britain. Among other things, members of the institution developed a declaration of rights and grievances.

In May 1775, delegates met again in the Second Continental Congress. By this time, war with Great Britain had already begun, following skirmishes between colonial militiamen and British troops at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. Congress drafted a Declaration of Causes explaining the colonies’ reasons for rebellion. On July 2, 1776, Congress declared American independence from Britain and two days later signed the Declaration of Independence.

Drafted by Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration of Independence officially proclaimed the colonies’ separation from Britain. In it, Jefferson eloquently laid out the reasons for rebellion. God, he wrote, had given everyone the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. People had created governments to protect these rights and consented to be governed by them so long as government functioned as intended. However, “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.” Britain had deprived the colonists of their rights. The king had “establish[ed] . . . an absolute Tyranny over these States.” Just as their English forebears had removed King James II from the throne in 1689, the colonists now wished to establish a new rule.

Jefferson then proceeded to list the many ways in which the British monarch had abused his power and failed in his duties to his subjects. The king, Jefferson charged, had taxed the colonists without the consent of their elected representatives, interfered with their trade, denied them the right to trial by jury, and deprived them of their right to self-government. Such intrusions on their rights could not be tolerated. With their signing of the Declaration of Independence (Figure 2.5), the founders of the United States committed themselves to the creation of a new kind of government.

The Articles of Confederation

Overview

Waging a successful war against Great Britain required that the individual colonies, now sovereign states that often distrusted one another, form a unified nation with a central government capable of directing the country’s defense. Gaining recognition and aid from foreign nations would also be easier if the new United States had a national government able to borrow money and negotiate treaties. Accordingly, the Second Continental Congress called upon its delegates to create a new government strong enough to win the country’s independence but not so powerful that it would deprive people of the very liberties for which they were fighting.

Putting a New Government in Place

The final draft of the Articles of Confederation, which formed the basis of the new nation’s government, was accepted by Congress in November 1777 and submitted to the states for ratification. It would not become the law of the land until all thirteen states had approved it. Within two years, all except Maryland had done so. Maryland argued that all territory west of the Appalachians, to which some states had laid claim, should instead be held by the national government as public land for the benefit of all the states. When the last of these states, Virginia, relinquished its land claims in early 1781, Maryland approved the Articles.4 A few months later, the British surrendered.

Americans wished their new government to be a republic, a regime in which the people, not a monarch, held power and elected representatives to govern according to the rule of law. Many, however, feared that a nation as large as the United States could not be ruled effectively as a republic. Many also worried that even a government of representatives elected by the people might become too powerful and overbearing. Thus, a confederation was created—an entity in which independent, self-governing states form a union for the purpose of acting together in areas such as defense. Fearful of replacing one oppressive national government with another, however, the framers of the Articles of Confederation created an alliance of sovereign states held together by a weak central government.

Following the Declaration of Independence, each of the thirteen states had drafted and ratified a constitution providing for a republican form of government in which political power rested in the hands of the people, although the right to vote was limited to free (white) men, and the property requirements for voting differed among the states. Each state had a governor and an elected legislature. In the new nation, the states remained free to govern their residents as they wished. The central government had authority to act in only a few areas, such as national defense, in which the states were assumed to have a common interest (and would, indeed, have to supply militias). This arrangement was meant to prevent the national government from becoming too powerful or abusing the rights of individual citizens. In the careful balance between power for the national government and liberty for the states, the Articles of Confederation favored the states.

Thus, powers given to the central government were severely limited. The Confederation Congress, formerly the Continental Congress, had the authority to exchange ambassadors and make treaties with foreign governments and Indian tribes, declare war, coin currency and borrow money, and settle disputes between states. Each state legislature appointed delegates to the Congress; these men could be recalled at any time. Regardless of its size or the number of delegates it chose to send, each state would have only one vote. Delegates could serve for no more than three consecutive years, lest a class of elite professional politicians develop. The nation would have no independent chief executive or judiciary. Nine votes were required before the central government could act, and the Articles of Confederation could be changed only by unanimous approval of all thirteen states.

What Went Wrong with the Articles?

The Articles of Confederation satisfied the desire of those in the new nation who wanted a weak central government with limited power. Ironically, however, their very success led to their undoing. It soon became apparent that, while they protected the sovereignty of the states, the Articles had created a central government too weak to function effectively.

One of the biggest problems was that the national government had no power to impose taxes. To avoid any perception of “taxation without representation,” the Articles of Confederation allowed only state governments to levy taxes. To pay for its expenses, the national government had to request money from the states, which were required to provide funds in proportion to the value of the land within their borders. The states, however, were often negligent in this duty, and the national government was underfunded. Without money, it could not pay debts owed from the Revolution and had trouble conducting foreign affairs. For example, the inability of the U.S. government to raise sufficient funds to compensate colonists who had remained loyal to Great Britain for their property losses during and after the American Revolution was one of the reasons the British refused to evacuate the land west of the Appalachians. The new nation was also unable to protect American ships from attacks by the Barbary pirates.5 Foreign governments were also, understandably, reluctant to loan money to a nation that might never repay it because it lacked the ability to tax its citizens.

The fiscal problems of the central government meant that the currency it issued, called the Continental, was largely worthless and people were reluctant to use it. Furthermore, while the Articles of Confederation had given the national government the power to coin money, they had not prohibited the states from doing so as well. As a result, numerous state banks issued their own banknotes, which had the same problems as the Continental. People who were unfamiliar with the reputation of the banks that had issued the banknotes often refused to accept them as currency. This reluctance, together with the overwhelming debts of the states, crippled the young nation’s economy.

The country’s economic woes were made worse by the fact that the central government also lacked the power to impose tariffs on foreign imports or regulate interstate commerce. Thus, it was unable to prevent British merchants from flooding the U.S. market with low-priced goods after the Revolution, and American producers suffered from the competition. Compounding the problem, states often imposed tariffs on items produced by other states and otherwise interfered with their neighbors’ trade.

The national government also lacked the power to raise an army or navy. Fears of a standing army in the employ of a tyrannical government had led the writers of the Articles of Confederation to leave defense largely to the states. Although the central government could declare war and agree to peace, it had to depend upon the states to provide soldiers. If state governors chose not to honor the national government’s request, the country would lack an adequate defense. This was quite dangerous at a time when England and Spain still controlled large portions of North America (Table 2.1).

The weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, already recognized by many, became apparent to all as a result of an uprising of Massachusetts farmers, led by Daniel Shays. Known as Shays’ Rebellion, the incident panicked the governor of Massachusetts, who called upon the national government for assistance. However, with no power to raise an army, the government had no troops at its disposal. After several months, Massachusetts crushed the uprising with the help of local militias and privately funded armies, but wealthy people were frightened by this display of unrest on the part of poor men and by similar incidents taking place in other states.6 To find a solution and resolve problems related to commerce, members of Congress called for a revision of the Articles of Confederation.

Shays’ Rebellion: Symbol of Disorder and Impetus to Act

In the summer of 1786, farmers in western Massachusetts were heavily in debt, facing imprisonment and the loss of their lands. They owed taxes that had gone unpaid while they were away fighting the British during the Revolution. The Continental Congress had promised to pay them for their service, but the national government did not have sufficient money. Moreover, the farmers were unable to meet the onerous new tax burden Massachusetts imposed in order to pay its own debts from the Revolution.

Led by Daniel Shays (Figure 2.6), the heavily indebted farmers marched to a local courthouse demanding relief. Faced with the refusal of many Massachusetts militiamen to arrest the rebels, with whom they sympathized, Governor James Bowdoin called upon the national government for aid, but none was available. The uprising was finally brought to an end the following year by a privately funded militia after the protestors’ unsuccessful attempt to raid the Springfield Armory.

The Development of the Constitution

Overview

In 1786, Virginia and Maryland invited delegates from the other eleven states to meet in Annapolis, Maryland, for the purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation. However, only five states sent representatives. Because all thirteen states had to agree to any alteration of the Articles, the convention in Annapolis could not accomplish its goal. Two of the delegates, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, requested that all states send delegates to a convention in Philadelphia the following year to attempt once again to revise the Articles of Confederation. All the states except Rhode Island chose delegates to send to the meeting, a total of seventy men in all, but many did not attend. Among those not in attendance were John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both of whom were overseas representing the country as diplomats. Because the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation proved impossible to overcome, the convention that met in Philadelphia in 1787 decided to create an entirely new government.

Points of Contention

Fifty-five delegates arrived in Philadelphia in May 1787 for the meeting that became known as the Constitutional Convention. Many wanted to strengthen the role and authority of the national government but feared creating a central government that was too powerful. They wished to preserve state autonomy, although not to a degree that prevented the states from working together collectively or made them entirely independent of the will of the national government. While seeking to protect the rights of individuals from government abuse, they nevertheless wished to create a society in which concerns for law and order did not give way in the face of demands for individual liberty. They wished to give political rights to all free men but also feared mob rule, which many felt would have been the result of Shays’ Rebellion had it succeeded. Delegates from small states did not want their interests pushed aside by delegations from more populous states like Virginia. And everyone was concerned about slavery. Representatives from southern states worried that delegates from states where it had been or was being abolished might try to outlaw the institution. Those who favored a nation free of the influence of slavery feared that southerners might attempt to make it a permanent part of American society. The only decision that all could agree on was the election of George Washington, the former commander of the Continental Army and hero of the American Revolution, as the president of the convention.

The Question of Representation: Small States vs. Large States

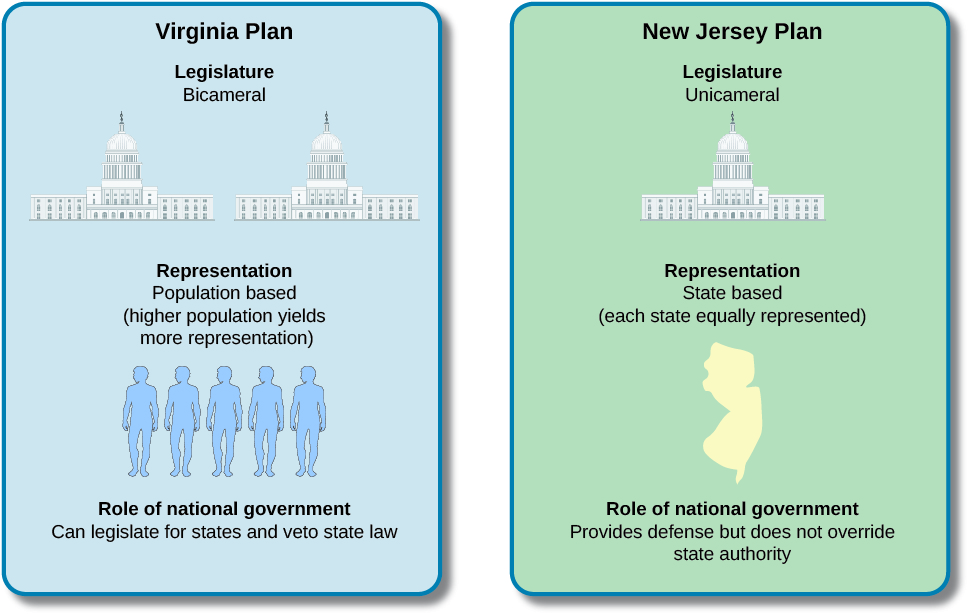

One of the first differences among the delegates to become clear was between those from large states, such as New York and Virginia, and those who represented small states, like Delaware. When discussing the structure of the government under the new constitution, the delegates from Virginia called for a bicameral legislature consisting of two houses. The number of a state’s representatives in each house was to be based on the state’s population. In each state, representatives in the lower house would be elected by popular vote. These representatives would then select their state’s representatives in the upper house from among candidates proposed by the state’s legislature. Once a representative’s term in the legislature had ended, the representative could not be reelected until an unspecified amount of time had passed.

Delegates from small states objected to this Virginia Plan. Another proposal, the New Jersey Plan, called for a unicameral legislature with one house, in which each state would have one vote. Thus, smaller states would have the same power in the national legislature as larger states. However, the larger states argued that because they had more residents, they should be allotted more legislators to represent their interests (Figure 2.7).

Slavery and Freedom

Another fundamental division separated the states. Following the Revolution, some of the northern states had either abolished slavery or instituted plans by which slaves would gradually be emancipated. Pennsylvania, for example, had passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. All people born in the state to enslaved mothers after the law’s passage would become indentured servants to be set free at age twenty-eight. In 1783, Massachusetts had freed all enslaved people within the state. Many Americans believed slavery was opposed to the ideals stated in the Declaration of Independence. Others felt it was inconsistent with the teachings of Christianity. Some feared for the safety of the country’s white population if the number of slaves and white Americans’ reliance on them increased. Although some southerners shared similar sentiments, none of the southern states had abolished slavery and none wanted the Constitution to interfere with the institution. In addition to supporting the agriculture of the South, slaves could be taxed as property and counted as population for purposes of a state’s representation in the government.

Federal Supremacy vs. State Sovereignty

Perhaps the greatest division among the states split those who favored a strong national government and those who favored limiting its powers and allowing states to govern themselves in most matters. Supporters of a strong central government argued that it was necessary for the survival and efficient functioning of the new nation. Without the authority to maintain and command an army and navy, the nation could not defend itself at a time when European powers still maintained formidable empires in North America. Without the power to tax and regulate trade, the government would not have enough money to maintain the nation’s defense, protect American farmers and manufacturers from foreign competition, create the infrastructure necessary for interstate commerce and communications, maintain foreign embassies, or pay federal judges and other government officials. Furthermore, other countries would be reluctant to loan money to the United States if the federal government lacked the ability to impose taxes in order to repay its debts. Besides giving more power to populous states, the Virginia Plan also favored a strong national government that would legislate for the states in many areas and would have the power to veto laws passed by state legislatures.

Others, however, feared that a strong national government might become too powerful and use its authority to oppress citizens and deprive them of their rights. They advocated a central government with sufficient authority to defend the nation but insisted that other powers be left to the states, which were believed to be better able to understand and protect the needs and interests of their residents. Such delegates approved the approach of the New Jersey Plan, which retained the unicameral Congress that had existed under the Articles of Confederation. It gave additional power to the national government, such as the power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce and to compel states to comply with laws passed by Congress. However, states still retained a lot of power, including power over the national government. Congress, for example, could not impose taxes without the consent of the states. Furthermore, the nation’s chief executive, appointed by the Congress, could be removed by Congress if state governors demanded it.

Individual Liberty vs. Social Stability

The belief that the king and Parliament had deprived colonists of their liberties had led to the Revolution, and many feared the government of the United States might one day attempt to do the same. They wanted and expected their new government to guarantee the rights of life, liberty, and property. Others believed it was more important for the national government to maintain order, and this might require it to limit personal liberty at times. All Americans, however, desired that the government not intrude upon people’s rights to life, liberty, and property without reason.

Compromise and the Constitutional Design of American Government

Overview

Beginning in May 1787 and throughout the long, hot Philadelphia summer, the delegations from twelve states discussed, debated, and finally—after compromising many times—by September had worked out a new blueprint for the nation. The document they created, the U.S. Constitution, was an ingenious instrument that allayed fears of a too-powerful central government and solved the problems that had beleaguered the national government under the Articles of Confederation. For the most part, it also resolved the conflicts between small and large states, northern and southern states, and those who favored a strong federal government and those who argued for state sovereignty.

The Great Compromise

The Constitution consists of a preamble and seven articles. The first three articles divide the national government into three branches—Congress, the executive branch, and the federal judiciary—and describe the powers and responsibilities of each. In Article I, ten sections describe the structure of Congress, the basis for representation and the requirements for serving in Congress, the length of Congressional terms, and the powers of Congress. The national legislature created by the article reflects the compromises reached by the delegates regarding such issues as representation, slavery, and national power.

After debating at length over whether the Virginia Plan or the New Jersey Plan provided the best model for the nation’s legislature, the framers of the Constitution had ultimately arrived at what is called the Great Compromise, suggested by Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Congress, it was decided, would consist of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Each state, regardless of size, would have two senators, making for equal representation as in the New Jersey Plan. Representation in the House would be based on population. Senators were to be appointed by state legislatures, a variation on the Virginia Plan. Members of the House of Representatives would be popularly elected by the voters in each state. Elected members of the House would be limited to two years in office before having to seek reelection, and those appointed to the Senate by each state’s political elite would serve a term of six years.

Congress was given great power, including the power to tax, maintain an army and a navy, and regulate trade and commerce. Congress had authority that the national government lacked under the Articles of Confederation. It could also coin and borrow money, grant patents and copyrights, declare war, and establish laws regulating naturalization and bankruptcy. While legislation could be proposed by either chamber of Congress, it had to pass both chambers by a majority vote before being sent to the president to be signed into law, and all bills to raise revenue had to begin in the House of Representatives. Only those men elected by the voters to represent them could impose taxes upon them. There would be no more taxation without representation.

The Three-Fifths Compromise and the Debates over Slavery

The Great Compromise that determined the structure of Congress soon led to another debate, however. When states took a census of their population for the purpose of allotting House representatives, should slaves be counted? Southern states were adamant that they should be, while delegates from northern states were vehemently opposed, arguing that representatives from southern states could not represent the interests of enslaved people. If slaves were not counted, however, southern states would have far fewer representatives in the House than northern states did. For example, if South Carolina were allotted representatives based solely on its free population, it would receive only half the number it would have received if slaves, who made up approximately 43 percent of the population, were included.7

The Three-Fifths Compromise, illustrated in Figure 2.8, resolved the impasse, although not in a manner that truly satisfied anyone. For purposes of Congressional apportionment, slaveholding states were allowed to count all their free population, including free African Americans and 60 percent (three-fifths) of their enslaved population. To mollify the north, the compromise also allowed counting 60 percent of a state’s slave population for federal taxation, although no such taxes were ever collected. Another compromise regarding the institution of slavery granted Congress the right to impose taxes on imports in exchange for a twenty-year prohibition on laws attempting to ban the importation of slaves to the United States, which would hurt the economy of southern states more than that of northern states. Because the southern states, especially South Carolina, had made it clear they would leave the convention if abolition were attempted, no serious effort was made by the framers to abolish slavery in the new nation, even though many delegates disapproved of the institution.

Indeed, the Constitution contained two protections for slavery. Article I postponed the abolition of the foreign slave trade until 1808, and in the interim, those in slaveholding states were allowed to import as many slaves as they wished.8 Furthermore, the Constitution placed no restrictions on the domestic slave trade, so residents of one state could still sell enslaved people to other states. Article IV of the Constitution—which, among other things, required states to return fugitives to the states where they had been charged with crimes—also prevented slaves from gaining their freedom by escaping to states where slavery had been abolished. Clause 3 of Article IV (known as the fugitive slave clause) allowed slave owners to reclaim their human property in the states where slaves had fled.9

Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances

Although debates over slavery and representation in Congress occupied many at the convention, the chief concern was the challenge of increasing the authority of the national government while ensuring that it did not become too powerful. The framers resolved this problem through a separation of powers, dividing the national government into three separate branches and assigning different responsibilities to each one, as shown in Figure 2.9. They also created a system of checks and balances by giving each of three branches of government the power to restrict the actions of the others, thus requiring them to work together.

Congress was given the power to make laws, but the executive branch, consisting of the president and the vice president, and the federal judiciary, notably the Supreme Court, were created to, respectively, enforce laws and try cases arising under federal law. Neither of these branches had existed under the Articles of Confederation. Thus, Congress can pass laws, but its power to do so can be checked by the president, who can veto potential legislation so that it cannot become a law. Later, in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison, the U.S. Supreme Court established its own authority to rule on the constitutionality of laws, a process called judicial review.

Other examples of checks and balances include the ability of Congress to limit the president’s veto. Should the president veto a bill passed by both houses of Congress, the bill is returned to Congress to be voted on again. If the bill passes both the House of Representatives and the Senate with a two-thirds vote in its favor, it becomes law even though the president has refused to sign it.

Congress is also able to limit the president’s power as commander-in-chief of the armed forces by refusing to declare war or provide funds for the military. To date, the Congress has never refused a president’s request for a declaration of war. The president must also seek the advice and consent of the Senate before appointing members of the Supreme Court and ambassadors, and the Senate must approve the ratification of all treaties signed by the president. Congress may even remove the president from office. To do this, both chambers of Congress must work together. The House of Representatives impeaches the president by bringing formal charges against him or her, and the Senate tries the case in a proceeding overseen by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The president is removed from office if found guilty.

According to political scientist Richard Neustadt, the system of separation of powers and checks and balances does not so much allow one part of government to control another as it encourages the branches to cooperate. Instead of a true separation of powers, the Constitutional Convention “created a government of separated institutions sharing powers.”10 For example, knowing the president can veto a law he or she disapproves, Congress will attempt to draft a bill that addresses the president’s concerns before sending it to the White House for signing. Similarly, knowing that Congress can override a veto, the president will use this power sparingly.

Federal Power vs. State Power

The strongest guarantee that the power of the national government would be restricted and the states would retain a degree of sovereignty was the framers’ creation of a federal system of government. In a federal system, power is divided between the federal (or national) government and the state governments. Great or explicit powers, called enumerated powers, were granted to the federal government to declare war, impose taxes, coin and regulate currency, regulate foreign and interstate commerce, raise and maintain an army and a navy, maintain a post office, make treaties with foreign nations and with Native American tribes, and make laws regulating the naturalization of immigrants.

All powers not expressly given to the national government, however, were intended to be exercised by the states. These powers are known as reserved powers (Figure 2.10). Thus, states remained free to pass laws regarding such things as intrastate commerce (commerce within the borders of a state) and marriage. Some powers, such as the right to levy taxes, were given to both the state and federal governments. Both the states and the federal government have a chief executive to enforce the laws (a governor and the president, respectively) and a system of courts.

Although the states retained a considerable degree of sovereignty, the supremacy clause in Article VI of the Constitution proclaimed that the Constitution, laws passed by Congress, and treaties made by the federal government were “the supreme Law of the Land.” In the event of a conflict between the states and the national government, the national government would triumph. Furthermore, although the federal government was to be limited to those powers enumerated in the Constitution, Article I provided for the expansion of Congressional powers if needed. The “necessary and proper” clause of Article I provides that Congress may “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing [enumerated] Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”

The Constitution also gave the federal government control over all “Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.” This would prove problematic when, as the United States expanded westward and population growth led to an increase in the power of the northern states in Congress, the federal government sought to restrict the expansion of slavery into newly acquired territories.

The Ratification of the Constitution

Overview

On September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia voted to approve the document they had drafted over the course of many months. Some did not support it, but the majority did. Before it could become the law of the land, however, the Constitution faced another hurdle. It had to be ratified by the states.

The Ratification Process

Article VII, the final article of the Constitution, required that before the Constitution could become law and a new government could form, the document had to be ratified by nine of the thirteen states. Eleven days after the delegates at the Philadelphia convention approved it, copies of the Constitution were sent to each of the states, which were to hold ratifying conventions to either accept or reject it.

This approach to ratification was an unusual one. Since the authority inherent in the Articles of Confederation and the Confederation Congress had rested on the consent of the states, changes to the nation’s government should also have been ratified by the state legislatures. Instead, by calling upon state legislatures to hold ratification conventions to approve the Constitution, the framers avoided asking the legislators to approve a document that would require them to give up a degree of their own power. The men attending the ratification conventions would be delegates elected by their neighbors to represent their interests. They were not being asked to relinquish their power; in fact, they were being asked to place limits upon the power of their state legislators, whom they may not have elected in the first place. Finally, because the new nation was to be a republic in which power was held by the people through their elected representatives, it was considered appropriate to leave the ultimate acceptance or rejection of the Constitution to the nation’s citizens. If convention delegates, who were chosen by popular vote, approved it, then the new government could rightly claim that it ruled with the consent of the people.

The greatest sticking point when it came to ratification, as it had been at the Constitutional Convention itself, was the relative power of the state and federal governments. The framers of the Constitution believed that without the ability to maintain and command an army and navy, impose taxes, and force the states to comply with laws passed by Congress, the young nation would not survive for very long. But many people resisted increasing the powers of the national government at the expense of the states. Virginia’s Patrick Henry, for example, feared that the newly created office of president would place excessive power in the hands of one man. He also disapproved of the federal government’s new ability to tax its citizens. This right, Henry believed, should remain with the states.

Other delegates, such as Edmund Randolph of Virginia, disapproved of the Constitution because it created a new federal judicial system. Their fear was that the federal courts would be too far away from where those who were tried lived. State courts were located closer to the homes of both plaintiffs and defendants, and it was believed that judges and juries in state courts could better understand the actions of those who appeared before them. In response to these fears, the federal government created federal courts in each of the states as well as in Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, and Kentucky, which was part of Virginia.11

Perhaps the greatest source of dissatisfaction with the Constitution was that it did not guarantee protection of individual liberties. State governments had given jury trials to residents charged with violating the law and allowed their residents to possess weapons for their protection. Some had practiced religious tolerance as well. The Constitution, however, did not contain reassurances that the federal government would do so. Although it provided for habeas corpus and prohibited both a religious test for holding office and granting noble titles, some citizens feared the loss of their traditional rights and the violation of their liberties. This led many of the Constitution’s opponents to call for a bill of rights and the refusal to ratify the document without one. The lack of a bill of rights was especially problematic in Virginia, as the Virginia Declaration of Rights was the most extensive rights-granting document among the states. The promise that a bill of rights would be drafted for the Constitution persuaded delegates in many states to support ratification.12

It was clear how some states would vote. Smaller states, like Delaware, favored the Constitution. Equal representation in the Senate would give them a degree of equality with the larger states, and a strong national government with an army at its command would be better able to defend them than their state militias could. Larger states, however, had significant power to lose. They did not believe they needed the federal government to defend them and disliked the prospect of having to provide tax money to support the new government. Thus, from the very beginning, the supporters of the Constitution feared that New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would refuse to ratify it. That would mean all nine of the remaining states would have to, and Rhode Island, the smallest state, was unlikely to do so. It had not even sent delegates to the convention in Philadelphia. And even if it joined the other states in ratifying the document and the requisite nine votes were cast, the new nation would not be secure without its largest, wealthiest, and most populous states as members of the union.

The Ratification Campaign

On the question of ratification, citizens quickly separated into two groups: Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The Federalists supported it. They tended to be among the elite members of society—wealthy and well-educated landowners, businessmen, and former military commanders who believed a strong government would be better for both national defense and economic growth. A national currency, which the federal government had the power to create, would ease business transactions. The ability of the federal government to regulate trade and place tariffs on imports would protect merchants from foreign competition. Furthermore, the power to collect taxes would allow the national government to fund internal improvements like roads, which would also help businessmen. Support for the Federalists was especially strong in New England.

Opponents of ratification were called Anti-Federalists. Anti-Federalists feared the power of the national government and believed state legislatures, with which they had more contact, could better protect their freedoms. Although some Anti-Federalists, like Patrick Henry, were wealthy, most distrusted the elite and believed a strong federal government would favor the rich over those of “the middling sort.” This was certainly the fear of Melancton Smith, a New York merchant and landowner, who believed that power should rest in the hands of small, landowning farmers of average wealth who “are more temperate, of better morals and less ambitious than the great.”14 Even members of the social elite, like Henry, feared that the centralization of power would lead to the creation of a political aristocracy, to the detriment of state sovereignty and individual liberty.

Related to these concerns were fears that the strong central government Federalists advocated for would levy taxes on farmers and planters, who lacked the hard currency needed to pay them. Many also believed Congress would impose tariffs on foreign imports that would make American agricultural products less welcome in Europe and in European colonies in the western hemisphere. For these reasons, Anti-Federalist sentiment was especially strong in the South.

Some Anti-Federalists also believed that the large federal republic that the Constitution would create could not work as intended. Americans had long believed that virtue was necessary in a nation where people governed themselves (i.e., the ability to put self-interest and petty concerns aside for the good of the larger community). In small republics, similarities among members of the community would naturally lead them to the same positions and make it easier for those in power to understand the needs of their neighbors. In a larger republic, one that encompassed nearly the entire Eastern Seaboard and ran west to the Appalachian Mountains, people would lack such a strong commonality of interests.15

Likewise, Anti-Federalists argued, the diversity of religion tolerated by the Constitution would prevent the formation of a political community with shared values and interests. The Constitution contained no provisions for government support of churches or of religious education, and Article VI explicitly forbade the use of religious tests to determine eligibility for public office. This caused many, like Henry Abbot of North Carolina, to fear that government would be placed in the hands of “pagans . . . and Mahometans [Muslims].”16

It is difficult to determine how many people were Federalists and how many were Anti-Federalists in 1787. The Federalists won the day, but they may not have been in the majority. First, the Federalist position tended to win support among businessmen, large farmers, and, in the South, plantation owners. These people tended to live along the Eastern Seaboard. In 1787, most of the states were divided into voting districts in a manner that gave more votes to the eastern part of the state than to the western part.17 Thus, in some states, like Virginia and South Carolina, small farmers who may have favored the Anti-Federalist position were unable to elect as many delegates to state ratification conventions as those who lived in the east. Small settlements may also have lacked the funds to send delegates to the convention.18

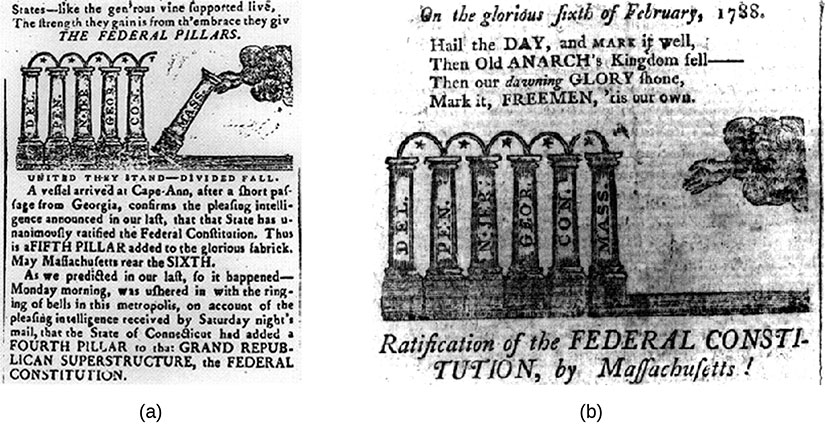

In all the states, educated men authored pamphlets and published essays and cartoons arguing either for or against ratification (Figure 2.11). Although many writers supported each position, it is the Federalist essays that are now best known. The arguments these authors put forth, along with explicit guarantees that amendments would be added to protect individual liberties, helped to sway delegates to ratification conventions in many states.

For obvious reasons, smaller, less populous states favored the Constitution and the protection of a strong federal government. As shown in Figure 2.12, Delaware and New Jersey ratified the document within a few months after it was sent to them for approval in 1787. Connecticut ratified it early in 1788. Some of the larger states, such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, also voted in favor of the new government. New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution in the summer of 1788.

Although the Constitution went into effect following ratification by New Hampshire, four states still remained outside the newly formed union. Two were the wealthy, populous states of Virginia and New York. In Virginia, James Madison’s active support and the intercession of George Washington, who wrote letters to the convention, changed the minds of many. Some who had initially opposed the Constitution, such as Edmund Randolph, were persuaded that the creation of a strong union was necessary for the country’s survival and changed their position. Other Virginia delegates were swayed by the promise that a bill of rights similar to the Virginia Declaration of Rights would be added after the Constitution was ratified. On June 25, 1788, Virginia became the tenth state to grant its approval.

The approval of New York was the last major hurdle. Facing considerable opposition to the Constitution in that state, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote a series of essays, beginning in 1787, arguing for a strong federal government and support of the Constitution (Figure 2.13). Later compiled as The Federalist and now known as The Federalist Papers, these eighty-five essays were originally published in newspapers in New York and other states under the name of Publius, a supporter of the Roman Republic.

The essays addressed a variety of issues that troubled citizens. For example, in Federalist No. 51, attributed to James Madison (Figure 2.14), the author assured readers they did not need to fear that the national government would grow too powerful. The federal system, in which power was divided between the national and state governments, and the division of authority within the federal government into separate branches would prevent any one part of the government from becoming too strong. Furthermore, tyranny could not arise in a government in which “the legislature necessarily predominates.” Finally, the desire of office holders in each branch of government to exercise the powers given to them, described as “personal motives,” would encourage them to limit any attempt by the other branches to overstep their authority. According to Madison, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Other essays countered different criticisms made of the Constitution and echoed the argument in favor of a strong national government. In Federalist No. 35, for example, Hamilton (Figure 2.14) argued that people’s interests could in fact be represented by men who were not their neighbors. Indeed, Hamilton asked rhetorically, would American citizens best be served by a representative “whose observation does not travel beyond the circle of his neighbors and his acquaintances” or by someone with more extensive knowledge of the world? To those who argued that a merchant and land-owning elite would come to dominate Congress, Hamilton countered that the majority of men currently sitting in New York’s state senate and assembly were landowners of moderate wealth and that artisans usually chose merchants, “their natural patron[s] and friend[s],” to represent them. An aristocracy would not arise, and if it did, its members would have been chosen by lesser men. Similarly, Jay reminded New Yorkers in Federalist No. 2 that union had been the goal of Americans since the time of the Revolution. A desire for union was natural among people of such “similar sentiments” who “were united to each other by the strongest ties,” and the government proposed by the Constitution was the best means of achieving that union.

Objections that an elite group of wealthy and educated bankers, businessmen, and large landowners would come to dominate the nation’s politics were also addressed by Madison in Federalist No. 10. Americans need not fear the power of factions or special interests, he argued, for the republic was too big and the interests of its people too diverse to allow the development of large, powerful political parties. Likewise, elected representatives, who were expected to “possess the most attractive merit,” would protect the government from being controlled by “an unjust and interested [biased in favor of their own interests] majority.”

For those who worried that the president might indeed grow too ambitious or king-like, Hamilton, in Federalist No. 68, provided assurance that placing the leadership of the country in the hands of one person was not dangerous. Electors from each state would select the president. Because these men would be members of a “transient” body called together only for the purpose of choosing the president and would meet in separate deliberations in each state, they would be free of corruption and beyond the influence of the “heats and ferments” of the voters. Indeed, Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 70, instead of being afraid that the president would become a tyrant, Americans should realize that it was easier to control one person than it was to control many. Furthermore, one person could also act with an “energy” that Congress did not possess. Making decisions alone, the president could decide what actions should be taken faster than could Congress, whose deliberations, because of its size, were necessarily slow. At times, the “decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch” of the chief executive might be necessary.

The arguments of the Federalists were persuasive, but whether they actually succeeded in changing the minds of New Yorkers is unclear. Once Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788, New York realized that it had little choice but to do so as well. If it did not ratify the Constitution, it would be the last large state that had not joined the union. Thus, on July 26, 1788, the majority of delegates to New York’s ratification convention voted to accept the Constitution. A year later, North Carolina became the twelfth state to approve. Alone and realizing it could not hope to survive on its own, Rhode Island became the last state to ratify, nearly two years after New York had done so.

Term Limits

One of the objections raised to the Constitution’s new government was that it did not set term limits for members of Congress or the president. Those who opposed a strong central government argued that this failure could allow a handful of powerful men to gain control of the nation and rule it for as long as they wished. Although the framers did not anticipate the idea of career politicians, those who supported the Constitution argued that reelecting the president and reappointing senators by state legislatures would create a body of experienced men who could better guide the country through crises. A president who did not prove to be a good leader would be voted out of office instead of being reelected. In fact, presidents long followed George Washington’s example and limited themselves to two terms. Only in 1951, after Franklin Roosevelt had been elected four times, was the Twenty-Second Amendment passed to restrict the presidency to two terms.

Constitutional Change

Overview

A major problem with the Articles of Confederation had been the nation’s inability to change them without the unanimous consent of all the states. The framers learned this lesson well. One of the strengths they built into the Constitution was the ability to amend it to meet the nation’s needs, reflect the changing times, and address concerns or structural elements they had not anticipated.

The Amendment Process

Since ratification in 1789, the Constitution has been amended only twenty-seven times. The first ten amendments were added in 1791. Responding to charges by Anti-Federalists that the Constitution made the national government too powerful and provided no protections for the rights of individuals, the newly elected federal government tackled the issue of guaranteeing liberties for American citizens. James Madison, a member of Congress from Virginia, took the lead in drafting nineteen potential changes to the Constitution.

Madison followed the procedure outlined in Article V that says amendments can originate from one of two sources. First, they can be proposed by Congress. Then, they must be approved by a two-thirds majority in both the House and the Senate before being sent to the states for potential ratification. States have two ways to ratify or defeat a proposed amendment. First, if three-quarters of state legislatures vote to approve an amendment, it becomes part of the Constitution. Second, if three-quarters of state-ratifying conventions support the amendment, it is ratified. A second method of proposal of an amendment allows for the petitioning of Congress by the states: Upon receiving such petitions from two-thirds of the states, Congress must call a convention for the purpose of proposing amendments, which would then be forwarded to the states for ratification by the required three-quarters. All the current constitutional amendments were created using the first method of proposal (via Congress).

Having drafted nineteen proposed amendments, Madison submitted them to Congress. Only twelve were approved by two-thirds of both the Senate and the House of Representatives and sent to the states for ratification. Of these, only ten were accepted by three-quarters of the state legislatures. In 1791, these first ten amendments were added to the Constitution and became known as the Bill of Rights.

The ability to change the Constitution has made it a flexible, living document that can respond to the nation’s changing needs and has helped it remain in effect for more than 225 years. At the same time, the framers made amending the document sufficiently difficult that it has not been changed repeatedly; only seventeen amendments have been added since the ratification of the first ten (one of these, the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, was among Madison’s rejected nine proposals).

Key Constitutional Changes

The Bill of Rights was intended to quiet the fears of Anti-Federalists that the Constitution did not adequately protect individual liberties and thus encourage their support of the new national government. Many of these first ten amendments were based on provisions of the English Bill of Rights and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. For example, the right to bear arms for protection (Second Amendment), the right not to have to provide shelter and provision for soldiers in peacetime (Third Amendment), the right to a trial by jury (Sixth and Seventh Amendments), and protection from excessive fines and from cruel and unusual punishment (Eighth Amendment) are taken from the English Bill of Rights. The Fifth Amendment, which requires among other things that people cannot be deprived of their life, liberty, or property except by a legal proceeding, was also greatly influenced by English law as well as the protections granted to Virginians in the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

Other liberties, however, do not derive from British precedents. The protections for religion, speech, the press, and assembly that are granted by the First Amendment did not exist under English law. (The right to petition the government did, however.) The prohibition in the First Amendment against the establishment of an official church by the federal government differed significantly from both English precedent and the practice of several states that had official churches. The Fourth Amendment, which protects Americans from unwarranted search and seizure of their property, was also new.

The Ninth and Tenth Amendments were intended to provide yet another assurance that people’s rights would be protected and that the federal government would not become too powerful. The Ninth Amendment guarantees that liberties extend beyond those described in the preceding documents. This was an important acknowledgment that the protected rights were extensive, and the government should not attempt to interfere with them. The Supreme Court, for example, has held that the Ninth Amendment protects the right to privacy even though none of the preceding amendments explicitly mentions this right. The Tenth Amendment, one of the first submitted to the states for ratification, ensures that states possess all powers not explicitly assigned to the federal government by the Constitution. This guarantee protects states’ reserved powers to regulate such things as marriage, divorce, and intrastate transportation and commerce, and to pass laws affecting education and public health and safety.

Of the later amendments only one, the Twenty-First, repealed another amendment, the Eighteenth, which had prohibited the manufacture, import, export, distribution, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. Other amendments rectify problems that have arisen over the years or that reflect changing times. For example, the Seventeenth Amendment, ratified in 1913, gave voters the right to directly elect U.S. senators. The Twentieth Amendment, which was ratified in 1933 during the Great Depression, moved the date of the presidential inauguration from March to January. In a time of crisis, like a severe economic depression, the president needed to take office almost immediately after being elected, and modern transportation allowed the new president to travel to the nation’s capital quicker than before. The Twenty-Second Amendment, added in 1955, limits the president to two terms in office, and the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, first submitted for ratification in 1789, regulates the implementation of laws regarding salary increases or decreases for members of Congress.

Of the remaining amendments, four are of especially great significance. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, ratified at the end of the Civil War, changed the lives of African Americans who had been held in slavery. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to African Americans and equal protection under the law regardless of race or color. It also prohibited states from depriving their residents of life, liberty, or property without a legal proceeding. Over the years, the Fourteenth Amendment has been used to require states to protect most of the same federal freedoms granted by the Bill of Rights.

The Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments extended the right to vote. The Constitution had given states the power to set voting requirements, but the states had used this authority to deny women the right to vote. Most states before the 1830s had also used this authority to deny suffrage to property-less men and often to African American men as well. When states began to change property requirements for voters in the 1830s, many that had allowed free, property-owning African American men to vote restricted the suffrage to white men. The Fifteenth Amendment gave men the right to vote regardless of race or color, but women were still prohibited from voting in most states. After many years of campaigns for suffrage, as shown in Figure 2.15, the Nineteenth Amendment finally gave women the right to vote in 1920.

Subsequent amendments further extended the suffrage. The Twenty-Third Amendment (1961) allowed residents of Washington, DC to vote for the president. The Twenty-Fourth Amendment (1964) abolished the use of poll taxes. Many southern states had used a poll tax, a tax placed on voting, to prevent poor African Americans from voting. Thus, the states could circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment; they argued that they were denying African American men and women the right to vote not because of their race but because of their inability to pay the tax. The last great extension of the suffrage occurred in 1971 in the midst of the Vietnam War. The Twenty-Sixth Amendment reduced the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen. Many people had complained that the young men who were fighting in Vietnam should have the right to vote for or against those making decisions that might literally mean life or death for them. Many other amendments have been proposed over the years, including an amendment to guarantee equal rights to women, but all have failed.

Originally published by Rice University, OpenStax CNX, Jan. 6, 2016, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/5bcc0e59-7345-421d-8507-a1e4608685e8@15.21