Emperor Xuan of Han decreed the ritual of worshipping the Five Sacred Mountains and Four Waterways.

By Aihua Jiang and Longxiang Ma

Minzu University of China

Abstract

The River God cult held a significant place in state rituals in imperial China. While scholars have primarily focused on the evolution of the River God sacrificial system, with its interplay of the official granting of noble titles and popular beliefs, this paper offers a further examination of the River God cult. By reading the “Stele of the (Shrine) Temple for the River God honored as the Duke of Numinous Source” (hedushen lingyuangong cimiao bei 河瀆神靈源公祠廟碑), created in the Tang Dynasty, this study explores the interactive relationship between the River God cult and state power in the Hezhong 河中area during that time period. We contend that the traditional River God cult and the participation of both officials and civilians in common rituals throughout past dynasties not only created a concentration of historical memories and reverent emotions but also established a strong social foundation for belief in the River God within the Hezhong region. This cult attracted both state endorsement and popular support. Thus, Guo Ziyi 郭子儀 (697–781), a famous military general in the Tang Dynasty, sought to renovate a temple and erect a monument for the River God. This monument was to serve as a cultural symbol that would strengthen the connection between the state and the local community, and hence ease the social tensions in the Hezhong area after the An Lushan Rebellion. In sum, such a construction would enhance the psychological and cultural identity of the people with both the mandate of heaven and the Tang imperial authority.

Introduction

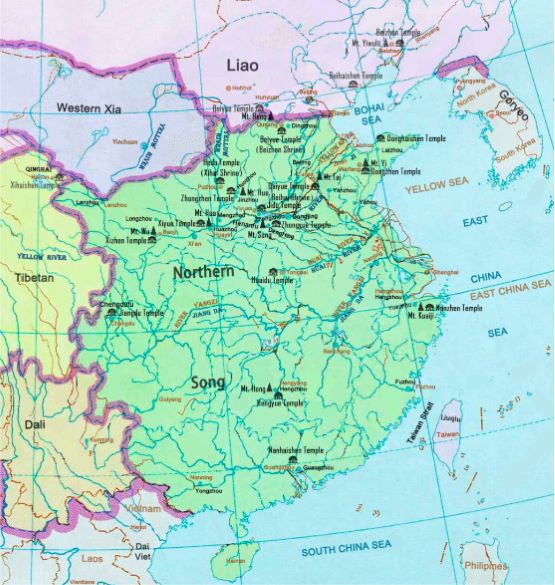

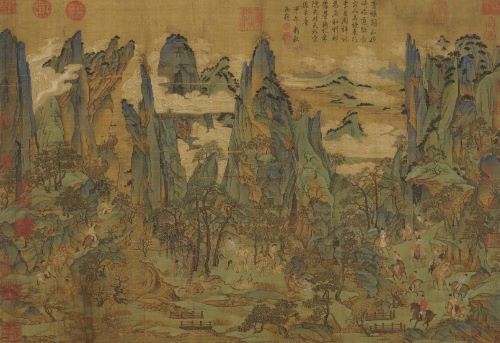

Under the influence of Confucianism, Emperor Xuan of Han 漢宣帝 decreed the ritual of worshipping the Five Sacred Mountains and Four Waterways (wuyuesidu 五岳四瀆), making them the highest-ranked natural entities of the state. For the following centuries, the Five Sacred Mountains and Four Waterways continued to be observed as subjects of state-level worship. The Four Waterways consisted of the Jiangdu 江瀆 (Yangtse River), the Hedu 河瀆 (Yellow River), the Huaidu 淮瀆 (Huai River), and the Jidu 濟瀆 (Ji River). In ancient literature, the “Hedu” refers to the Yellow River. As the ancestor of the Four Waterways, the Hedu held a prominent position in the tradition of national sacrifice. As time passed and rituals evolved, the Hedu gradually transcended its geographical identity, transforming from a mere natural entity into a deified figurehead in the minds of the people. Wang Wei 王瑋 and Wang Lachun 王腊春 explain the human–water relationship in ancient China from the perspective of witchcraft and ghost culture. In their opinion, the worship of the Yellow River stemmed from the ancient people’s limited self-awareness and geographical knowledge. They regarded the river as supernatural, prayed for its peace, feared its wrath, and directly worshipped and sacrificed to it (Wang and Wang 2020, pp. 93–103). With the advancement of understanding and the establishment and evolution of a national ideology, people’s initial reverence for rivers gradually transformed into a rationalized belief system. The natural attributes associated with the River God were progressively stripped away, giving rise to an increased emphasis on its social functions, with these functions gradually becoming multiplied. Simultaneously, the simple sacrificial rituals devoted to the River God evolved into a more complex maturity.

On the practice of sacrificing to the River God, Gan Mingfeng’s analysis of the ancient River God worship system systematically traces the traditional cultural elements of such worship from the perspectives of ritual status, temple relics, and the relationship between ritual and gods (Gan 2005, pp. 291–94). Then, in “The Sacrifice of the Yellow River and the Changes of River Temples”, Wang Yuanlin 王元林 and Ren Huizi 任慧子 explain the reasons behind the emergence of the River God and the gradual development of the Yellow River sacrificial ritual system over time. A multitude of Hedu Temples 河瀆廟 were constructed at both national and local levels, thereby demonstrating the significance of the Yellow River within the national ritual system and in the production and lives of the people (Wang and Ren 2008, pp. 20–23). Jia Jinhua 賈晉華 comprehensively studies the formation of the ancient Chinese landscape deity worship system and the religious and political concepts reflected therein, using a combination of religious, historical, geographical, and political research methods. She demonstrates how these geographical landmarks gradually combined with religious beliefs and ritual political institutions to become symbols of territorial, sacred, and political legitimacy that helped maintain the unity and governance of the traditional Chinese imperium for 2000 years (Jia 2021, p. 319). These studies summarized above provide us with a clear framework for understanding the evolution of the River God sacrificial system in ancient China.

Medieval Chinese customs refer more to folk activities than the classics; they can also be religious, although they may not be ritual activities led by monks or priests/sacrifices. Nevertheless, as sacrifices to the River God continued to be performed over the course of centuries, the concept of the River God itself also gradually gained secular reverence; that is, it was ingrained within the popular culture in the area regardless of the religion it originated from.

In January of the sixth year of the Tianbao 天寶 era (747), Emperor Xuanzong 玄宗 (r. 712–756) decided that “since the Five Sacred Mountains had already been crowned as kings, the Four Waterways should be elevated to the position of Duke 五嶽既已封王, 四瀆當升公位” (Liu 1975, p. 221). Therefore, he issued an edict to confer titles on the Four Waterways and nominated Hedu as the “Lingyuan Duke” (lingyuan gong 靈源公). In an article entitled “On the Granting of Festivals and Titles to Ancestral Temples during the Tang and Song Dynasties,” Japanese scholar Sue Takashi suggests the practice of granting quotas and titles during the Tang Dynasty was limited to major, medium, and minor ceremonies, and was neither institutionalized nor systematic. It was not until the late Tang and Five Dynasties period that local deities were granted titles, though there were not many (Sue 1994, pp. 96–119). In his article about changes to Tang dynasty temple policies, focusing on the numbers of titles granted, Korean scholar Kim Sang fan proposes that after Wu Zetian 武則天 (r. 690–705) began to bestow titles on some deities during the Tang Dynasty, this trend continued to expand. By the end of the Tang and the Five Dynasties periods, the scope of the awards went beyond national and quasi-national sacrificial temples, and even extended to general folk temples, thereby gradually forming another mechanism for regulating folk temple beliefs (Kim 2006, p. 2).

Behind the worship of deities in a certain period there is often an intricate relationship between state and society, and different modes of operation. In “Beyond Suburban Temples: Sui and Tang State Sacrifice and Religion”, Lei Wen points out that the sacrificial activities of local governments themselves reflect the lower limit of national ideology; that is, the degree of intervention in grassroots society (Lei 2009, p. 3). Pi Qingsheng explores the differences in strategies between central and local governments, as reflected in the matter of praying for rain, and observes the relationship between the Song court elites and folk gentry through the views and behaviors of the intellectual class regarding belief in temple gods (Pi 2008). As a part of such belief in temple gods, the River God has also received attention from scholars. For example, Niu Jianqiang’s article on river management and River God faith during the Ming Dynasty discusses the way frequent disasters on the Yellow River led to an increased demand from the people that blessings from the River God be sought in the river control project, thus giving belief in the River God a distinctly utilitarian feature (Niu 2011, pp. 51–68).

Academic research on the River God focuses primarily on the evolution of sacrificial systems and the correlation between state titles and beliefs about temple deities. However, these studies are broad and do not sufficiently explore the interactions between River God belief, state power, and local society. Furthermore, existing studies predominantly concentrate on the Song and Ming dynasties, leaving a dearth of research on River God belief during the Tang Dynasty.

During the reign of Emperor Daizong 代宗 (r. 762–779), Guo Ziyi built the “Lingyuan Temple Stele of the River God” in the Hezhong area,1 which provides an example of the interaction between belief in the River God, state power, and local society during the Tang Dynasty. As a text documenting the temple construction, this stele has the common features of praising the God and publicizing the achievements of the officials but also reflects a certain historical particularity. The present article focuses on this temple monument and explores the background and process of its construction from temporal and spatial perspectives. The article also examines the promotion of Guo Ziyi’s achievements and war history as described on the monument, as well as the insights the inscription offers into official worship of the River God and public beliefs. Additionally, it will reveal how the government utilized faith in the River God to control and integrate local society in the Hezhong area after the An Lushan Rebellion, in order to reshape the authority of the dynasty.

Time and Space: Background to the Establishment of the Temple Stele

Guo Ziyi guarded the Hezhong area in the reign of Emperor Daizong of Tang. He considered it to go against Confucian etiquette for the River God and the God’s relatives to be worshiped in the same room of the original temple. He therefore built a special residence, named Qin2 寢, to accommodate the wife of the River God. According to the Puzhou Fu Zhi 蒲州府志, ”The beginning of the Hedu Temple was built by Guo Ziyi” (Engraved in the 19th year of Qianlong, p. 216). However, it is speculated that before the Tang Dynasty, the Hedu Temple was simply a place of worship with a small scale. According to the legend, the River God and his relatives lived in the same room, so Guo Ziyi renovated the temple for the River God and set up a private quarters for the relatives of the River God. The inspector (Jiedu Xunguan 節度巡官) Wang Yanchang 王延昌 wrote and carved the “Stele of the Lingyuan Gong Temple of the River God” to commemorate this event. Zhao Mingcheng 趙明誠 from the Song Dynasty (960–1279) recorded this monument in his “Jinshi Lu 金石錄” (Zhao 2009, p. 68), and Zhu Changwen 朱長文 did so in his “Gujin Beitie Kao 古今碑帖考” (Zhu 1982, p. 13180). Unfortunately, the temple stele no longer exists. However, the full text of this monument, consisting of approximately 1400 words, is recorded in the “Wenyuan Yinghua 文苑英華” (Li 1966, pp. 4638–639). The inscription reviews the history of river worship, describes the story of the River God assisting Guo Ziyi in suppressing the An Lushan Rebellion, and outlines the process and results of Guo Ziyi’s construction of Qin Miao 寢廟. It incorporates many historical facts and is thus worth paying attention to.

The inscription on the temple stele does not explicitly indicate the specific time of its creation. The “Jinshi Lu” dates back to September of the third year of the Dali 大曆 era (768 AD) (Zhao 2009, p. 68), and information such as “After the death of Li Guozhen, Gong (郭子儀) took command of Jiangzhou for the second time. After Fugu Huaien’s rebellion, Gong defended Hedong for the second time 李国桢之遇祸,公复总戎故绛;仆固怀恩之逆命,公又出镇河东” and “Since taking over the army, Gong guarded our hometown three times 自公杖钺,三至我里”, which also indicate the time of the inscription. The Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 (Old Tang History) biography of Guo Ziyi states that the third time Guo Ziyi guarded Hezhong 河中 was in March of the third year of the Dali era (768 AD) (Liu 1975, p. 3463). The Tubo 吐蕃 attacked Lingwu 靈武 in August of that year. The first day of the next month, Emperor Daizong issued an edict ordering Guo Ziyi to move 50,000 soldiers from Hezhong to Fengtian 奉天 for defensive purposes (Sima 1956, p. 7204). The inscription mentions “having completed the mission in less than a month 曾不踰月,克復于成”. Taking into consideration the time constraints from construction to completion of the temple and monument, it is evident that Guo Ziyi had already agreed to this project before September, and the temple stele was completed after he left.

Regarding the location of the stele, the inscription states that it was “in Hexi County of Hezhong Fu 河中府河西縣”. However, the original site of the River God Temple is not there but in Linjin 臨晉 of Tongzhou 同州 (also named Chaoyi 朝邑), which was also the place where sacrifices occurred in Hedu before the Tang Dynasty. In the fifteenth year of the Kaiyuan 開元reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (727 AD), the River God Temple underwent a migration. According to an entry “Hexi County, Hezhong Fu” in the Geographical Records of Xin Tangshu 新唐書 (New Tang History), “In the fifteenth year of the Kaiyuan, the temple of the River God was relocated from Chaoyi County to Hexi County” (Ouyang 1975, p. 1000). The reason relates to a flood of the Luo River. According to the “Five Elements Annals” in the New Tang History, in July of that year “the Luo River overflowed and entered the city, with a depth of several meters. The dead were not counted, damage was caused to the city of Tongzhou and Pingyi County 馮翊縣, and there were more than two thousand households of floating residents 洛水溢,入鄜城,平地丈余,死者无算,坏同州城市及冯翊县,漂居民二千余家” (Ouyang 1975, p. 931). Given the fierce flood submerged the city of Tongzhou, the fate of the River God’s Temple, which was located downstream, can be imagined. Thus, the temple was relocated to a new site. The entry for “Hexi County” in the “Taiping Huanyu Ji 太平寰宇記” records that the “Temple of [the] river god is located one mile northwest of the Hexi county 河渎庙,在县正西北城外一里” (Yue 2007, p. 956). This information aligns with the account in the Xin Tangshu, which confirms the relocation of the River God’s temple to Hexi County.

Investigation of the temporal and spatial aspects surrounding the establishment of the monument reveals that the temple is situated one li 里 northwest of Hexi County, adjacent to Pujin Guan 蒲津關. In September of the third year of the Dali reign, Guo Ziyi renovated the temple and erected a monument here, which not only made it convenient to worship the Yellow River, but also attracted the attention of passersby, for it was located “in Yongzhou district, near the capital 在雍州之域,通天子之都”. Unlike buried epitaphs, which form a relatively private personal expression and remain unseen by people for a long time, large-scale inscriptions are often placed along main roads. They have a strong visual impact on pedestrians and serve as significant features of the landscape. Additionally, the inscriptions on these tablets function as public political declarations (Qiu 2012, p. 37). Coincidentally, after the completion of the temple stele, Guo Ziyi met the Emperor in October of that year, and shortly after returning to the river, relocated the Shuofang Jun 朔方軍 to Binzhou 邠州. Thereafter, this army guarded Pu 蒲(河中府) and Bin 邠, respectively (Sima 1956, p. 7204). Therefore, we have reason to believe that establishing such a monument at the time when Guo Ziyi was preparing to depart from Hezhong was not a whim, but rather possessed deeper political implications.

Praising the Gods and Recording Merit: Textual Expression in the Temple Stele

Ye Changchi 葉昌熾, a Qing Dynasty scholar, notes that “there are four purposes to erecting a monument 立碑之例,厥有四端”, i.e., describing virtue, inscribing achievements, recording events, and compiling speeches (Ye 2009, p. 665). Generally speaking, temple steles are erected beside temples, ancestral halls, and other buildings, thereby enabling passers-by to gain insights into the nature of these temples and ancestral buildings, as well as the achievements, morals, and behaviors of the worshippers (Xu and Wu 2002, p. 101). Zhao Chao 趙超 classifies temple steles as “merit steles (Gongde Bei 功德碑)”. He believes that the purpose of the temple monument—as inferred from its object and the content of the eulogy—is to exalt the divine spirit and benevolence while seeking divine protection (Zhao 2019, p. 139). Wang Qisun 王芑孫, another Qing Dynasty scholar, points out during a discussion of the “Yuedu Temple Stele Example” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, that most of the inscriptions in the Han Dynasty were the words of subordinates praising superiors. Although the stele of Yuedu 岳瀆 Temple was not specially created for this purpose, it also praises sacrifices and prayers in the middle or at the end of the inscription, which was also the origin of Changli 昌黎(韓愈) “Nanhai Shenmiao 南海神廟” and Dongpo 東坡(蘇軾) “Baozhong Guan 表忠觀” (Wang 1986, pp. 237–38). Wang Qisun suggests that the mode of temple inscriptions in the Tang and Song dynasties was inherited from the Eastern Han Dynasty. Indeed, since the Eastern Han Dynasty, the textual narrative tradition of temples and steles, which not only extols the efficacy of deities but also accentuates the accomplishments and virtues of local officials, has exerted a profound influence (Xia 2021, p. 21).

Specifically, Wang Yanchang also followed this tradition in the creation of his inscription. The inscription first describes the River God’s contribution to the protection of the Hezhong area, emphasizing that it is precisely because of the River God’s blessing that “the people are free from suffering and worry about floods 息昏墊之苦,絕羨溢之憂,濱河之人,闊無大害”. The River God also bestows favorable weather and, moreover, the people in this region remain healthy.

Secondly, the inscription attributes all of Guo Ziyi’s achievements in suppressing rebellions in the Hezhong region during the An Lushan Rebellion to the River God’s blessings. As indicated in the inscriptions on the stele, in February of the second year of Zhide 至德 (757 AD), Guo Ziyi sought the divine guidance of the River God prior to his departure from the Luo River. He then embarked upon his military campaign against Pingyi County. The rebel general, Cui Qianyou 崔乾祐, hastily retreated, thereby facilitating Guo Ziyi’s reconquest of Hedong. Subsequently, Guo Ziyi delegated his son, along with commanders (bingmashi 兵馬使) Li Shaoguang 李韶光 and General Wang Zuo 王祚, to traverse the Yellow River and penetrate through the strategic Tongguan 潼關. This strategic move led to the recapture of the pivotal Yongfeng granary 永豐倉. As Guo Ziyi’s forces lingered around the Yongfeng granary, the rebel forces surreptitiously encircled them. At this critical juncture, Guo Ziyi had a visionary dream, wherein the River God alerted him about the impending threat and advised him to execute a strategic withdrawal before the situation escalated. Indeed, without the protective guidance of the River God, the Tang army might have potentially faced complete annihilation. However, this battle was still a significant loss for the Tang army, with over ten thousand dead. The generals Li Shaoguang and Wang Zuo were killed in action, and Pugu Huai’en held a horse’s head to cross the Wei River, retreating to defend Hedong. Shortly after this incident, the Tang army bounced back and once again claimed victory.

The stele also narrates how the River God protected Guo Ziyi several times, stabilizing the situation in Hezhong, including resolving the confusion in Hezhong after Li Guozhen was killed and the rebellion of Pugu Huaien. The stele attributes Guo Ziyi’s undefeated record in Hezhong to the protection of the river god. In fact, when establishing the temple stele, Guo Ziyi also said, “The River God should be praised, not me 頌祗則可, 無推美於予”. The purpose behind Guo Ziyi’s construction of the temple stele extends beyond mere self-promotion, as is evident from the aforementioned statement. The relevant evidence dates back as early as the second year of Yongtai 永泰 (766 AD), when Huazhou Jiedushi 華州節度使, Zhou Zhiguang 周智光, the County Magistrate of Fengtian 奉天縣令, Cheng Xian 程暹, the common person Qiu Tingzhen 仇廷珍, and the monk Shan Hai 山海 submitted a petition requesting the establishment of an ancestral temple and monument for Guo Ziyi in Huazhou where he was born. This request was approved by the Emperor Daizong. However, considering that the state had not yet been pacified, Guo Ziyi instructed his staff member, Shao Yue 邵說, to submit four articles rejecting this proposal. He wrote that the Hebei military governorship had not been pacified, and we were occasionally raided and plundered by the northwest Tubo and Huihe 北有亡命之虜,西有無厭之戎. As a loyal minister of the Tang Dynasty, Guo Ziyi hoped to emulate the ancients and only after “pacifying the world” could he inscribe and erect stones.

As mentioned previously, in the third year of Dali, Guo Ziyi renovated the temple and erected a monument for the River God. His intention was not to commemorate his achievements, but rather to praise the River God and express gratitude for the blessings bestowed upon him during suppression of the rebellion. The River God held a revered position in the Hezhong region, not only safeguarding the Tang Dynasty, Guo Ziyi, and devout people, but also overseeing any transgressions and meting out punishment to rebels. Therefore, the inscription reads: “The River God dispels the country’s bad luck and opens up its land. The loyal ministers rely on the River God for protection, while treacherous officials are punished by the River God 國之氛霾,惟河公蕩滌;國之土宇,惟河公廓開;國之忠良,惟河公保祐;國之奸慝,惟河公殄摧”. The sanctity and authority of the River God were considered both admirable and terrifying. Officials would usually use the public attitude towards the gods to establish authority and maintain rule. Thus, belief in the River God could bring about the public’s submission and fear, which would function as external behavioral constraints, and regulate public activities and deter deviant behavior. At the same time, the River God served as a bridge and link between the government and the people. In this way it united people’s hearts at a psychological level, strengthened their cohesion and sense of identity, eased local social conflicts and contradictions, effectively maintained the political pattern, and integrated the social order in the Hezhong region.

The temple stele was inscribed in the third year of the Dali era, shortly after the suppression of the An Lushan Rebellion. The feudal lords in Hebei and the Tubo regime frequently posed a threat to the central government of Tang. The stele was also located adjacent to the Pujin Pass 蒲津關, a strategic location that connected Hebei in the north and Tubo to the west. This location demonstrates that the political intention behind the stele was not only to praise the achievements of the River God and Guo Ziyi, but also to highlight the glorious history of the Tang army, emphasizing the favor and protection of the River God towards the Tang Dynasty, Guo Ziyi, and the people in the Hezhong region, creating a political atmosphere in which fate was on the side of the Tang Dynasty. The widespread belief in deities among ancient people, along with this type of propaganda, would have effectively deterred potential threats such as those from the Hebei feudal lords and the Northwest Tubo, thereby maintaining social stability in the area.

Ritual and Faith: The Hedu Sacrifice in the Temple Stele

National sacrifice refers to all the sacrificial activities presided over by the emperor and all levels of government. In terms of the purpose of sacrifice, this activity is not for seeking personal blessings, but a way for the government to perform its social functions, which inherently possess a “public” nature. Local rituals and traditions are integrated into national sacrifice, permeating national power into the locality through fixed procedures and grand ceremonies, thereby strengthening the connection between the nation and the people. With the development of the national sacrifice system, the local deities were sacrificed by the local governor while still nominally showing the emperor’s dominance in the system.

Yuedu 岳瀆 was almost the highest ranking official sacrificial object in the local area, and it was also the limit and standard for local mountains, rivers, and other deities to be incorporated into the national sacrificial system. In the Tang Dynasty, the River God sacrificial ritual was a national ceremony with a fixed time, location, and specifications set by local officials. The “Liyuezhi” 禮樂志 (Records of Rites) in the Xin Tangshu record the following:

The Five Peaks, Four Strongholds, Four Seas and Four Waterways are a ritual held once a year… The West Sea西海 and the West Du 西瀆 (Hedu or River God), located in Tongzhou… They need to use Tai Lao太牢 four Bian 籩 and four Dou 豆 each for sacrificial offerings. The sacrificial officials were the local governors.

五嶽、四鎮、四海、四瀆,年別一祭,各以五郊迎氣日祭之……西海、西瀆大河,於同州……其牲皆用太牢,籩、豆各四,祀官以當界都督刺史充。

(Liu 1975, p. 910)

The sacrifice of Hedu in the early Tang Dynasty would have been held on the day marking the beginning of autumn in Tongzhou. In terms of ritual standards, in addition to the use of Tai Lao 太牢 (sacrifices consisting of an ox, a sheep, and a pig), there were also “Bian and Dou each four”, which were later added to “Bian Dou ten, Gui 簋 two, Fu 簠 two, and Zu 俎 three” (Ouyang 1975, p. 331), all of which were held by local governors as sacrificial officials. In the 25th year of the Kaiyuan reign of Emperor Xuanzong (737), envoys were sent to offer sacrifices to the Five Sacred Mountains and Four Waterways. In the first year of the Tianbao reign, envoys were sent to the Five Sacred Mountains, while the Four Waterways were still worshipped on a day chosen by local officials. Emperor Xuanzong continuously issued edicts conferring titles on Yuezhen Haidu 岳鎮海瀆 and local temples and sent envoys to offer sacrifices. At a time when national power was strong, he sought to declare this strong control over local society. In the second year of Yongtai 永泰, and due to the prolonged drought in spring and summer, more than ten officials, including Pei Mian, were ordered to offer sacrifices to Chuandu 川瀆 to pray for rain (Liu 1975, p. 916). Although sending envoys to worship the Five Sacred Mountains and the Four Sacrifices had become a norm, this was not an official ritual 舊禮,皆因郊祀望而祭之,天寶中,始有遣使祈福之祠,非禮之正也 (Ma 2011, p. 2552). In addition to the envoys, local officials still played the main role in many cases. We have not found a specific description in the historical records regarding local officials worshipping Hedu, but an article by Zhang Xian about the Jidu Temple 濟瀆廟 in the 13th year of Zhenyuan 貞元 (797) provides a point of reference:

On the day of welcoming winter, the Emperor ordered the Chengzhou Neishi to offer blessings, including a Cui crown, seven tassels, five emblems, sword, shoes, and jade pendants as the initial offerings. The county magistrate prepared a crown, six tassels, three emblems, sword, shoes, and jade pendants, as the second offerings. The Xiancheng (assistant of county magistrate) prepared a crown with five tassels, swords, shoes, and jade pendants as the final offerings. Sacrifices consisting of an ox, a sheep and a pig were used. The major affairs of the state must first be worshipped.

天子以迎冬之日,命成周內史奉祝文宿齊,毳冕、七旒、五章、劍履、玉佩,為之初獻;縣尹加繡冕、六旒、三章、劍履、玉佩,為之亞獻;邑丞元冕,加五旒,無章,亦劍履、玉佩,為之終獻。用三牲之享。邦之大事,先在祀乎!

(Dong 1983, p. 6396)

The Jidu Sacrifice mentioned in the article was held on the day marking the beginning of winter in Jiyuan County 濟源縣 of Luozhou 洛州. The “Chengzhou Neishi” refers to the governor of Henan Prefecture 河南府尹. The ceremony and specifications were in accordance with the system regulations (Xiao 2000, pp. 201–2). In addition, the Sidu 四瀆 sacrifice rites also included local officials’ prayers with specific formats. Li Jingrang李景讓 “Record of Guangyuan Temple in Nandu River 南瀆大江廣源公廟記” from the Dazhong 大中 period of Tang Dynasty provides us with an example:

The ancient ritual of Emperor Kaiyuan is in the form of an edict which reads: “In the fourth month of summer, when the morning falls. The prefect led his subordinates to sacrifice Nandu in Yizhou, and prepare jade baskets and wash Zun, Lei, Fu and Gui. I offer my blessings to the gods at the beginning of my reign, and kneel on my left and right to recite my words. The text reads: ‘A certain day, the emperor sent a certain official to announce to the Southern Du River. Only the Jiang God can gathers the river into the sea. Merit is shining and embellished, and virtue is manifested in longevity. Today, due to the beginning of summer, follow a set ceremony. these jade, silk, food as sacrifices offer to you Shang Xiang!’ The rule is still in use until the twelfth year of Dazhong; it has already been 112 years.

開元皇帝古禮是式,詔曰:惟夏四月,肇辰迎氣。太守其率祭官祀南瀆於益州,設玉筐及洗樽罍簠簋。既舉冪初獻,祝進神,左右跪揚我詞,其文曰:維某年歲次月朔(闕)子嗣天子遣某官某昭告於南瀆大江。惟神包總大川,朝宗於海。功昭潤化,德表靈長。今因夏首,用率常典。敬以玉帛犧牲粢盛庶品,明薦於神。尚饗!至於今不衰,詔之歲歲直丁亥,迨及戊寅當大中十二年,合一百一十有二歲。

(Dong 1983, p. 7925)

The specifications for Hedu 河瀆, Jidu 濟瀆, and Jiangdu 江瀆 are the same. From the above example, it can be seen that even in the late Tang Dynasty, the specifications and procedures of the Sidu sacrifices were generally in accordance with the regulations of the ritual system. Guo Ziyi sacrificed to the River God in Hezhong following the same specifications as the other three deities, with differences only in time, place, and title. The inscription describes Guo Ziyi as also choosing to bathe and fast on auspicious days, constantly worshipping and praying for rain, and praying for the blessings of the River God 奉牲玉不敢愛也,致精意未嘗怠也,每蠲吉曆選,自郊徂宮.

Through participation in the official worship ceremony, belief in the River God was continuously reinforced among the people in the Hezhong region. Not only did they set up shrines for worship where the River God resided, they also sculpted statues of the God’s relatives. As the inscription goes: “If it is enshrined between the halls, the brother and wife of the River God are present 奠於堂戶之間,則神之昆弟具在;酧於屋漏之內,則神之伉儷攸居”. This worship method reflects the anthropomorphism of the River God, thereby substantiating the prevailing fervor for the River God faith in the Hezhong region. This kind of ritual was not uncommon. In the Sui Dynasty there were statues of Yue Du 岳瀆 that were protected by law. In December of the 20th year of the Kaihuang 開皇 reign (600 AD), Emperor Wendi of Sui 隋文帝 issued an edict:

The Five Sacred Mountains and Four Towns celebrate the rain and clouds, and the Yangtse River, Yellow River, Huai River, and Ji River nourish the area and people. Therefore, temples are built and worshipped to show respect at all times. Those who dare to destroy or steal Buddha, taoism and Yuezhenhaidu statues will be considered as immoral.

其五嶽四鎮,節宣雲雨,江、河、淮、海,浸潤區域,並生養萬物,利益兆人,故建廟立祀,以時恭敬。敢有毀壞偷盜佛及天尊像、嶽鎮海瀆神形者,以不道論。

(Wei 1973, pp. 45–46)

This sacrificial method continued to be used in the Tang Dynasty, but Guo Ziyi believed that worshipping the River God and his relatives together in the same room was against Confucian etiquette. There was therefore a requirement to “build a hall in the back 筑館于後”, which allowed the River God’s wife to live in a separate room. Thanks to the tradition of national River God sacrifices and the grand scale of ritual display, belief in the River God was quite popular in the Hezhong region. Belief in the River God was not only reflected in the official ceremonial worship process, but as a representative deity of the Hezhong region; it was also reflected in the worship of the people. As this worship became localized and gradually institutionalized, it became an important component of the belief system of the people in the Hezhong region.3

Government and the People: Social Participation in the Temple Stele

When the local social order is disrupted or disordered to a certain extent due to internal or external pressures, local authorities often focus on strengthening social control and enhancing cohesion among various societal strata by tapping into local folk beliefs. The government strengthens local cultural traditions to promote the integration of different groups within the governed region and to maintain local social stability. After the An Lushan Rebellion, the Hezhong region emerged as the primary battleground between the Tang Dynasty and rebel forces, significantly impeding local socio-economic progress. Additionally, following the suppression of the An Lushan Rebellion, the Shuofangjun 朔方軍 engaged in multiple confrontations with local forces upon entering the Hezhong region, resulting in significant distress for the local populace, who then urgently relied on the power of the gods for spiritual comfort. As a representative deity in the local area, the River God naturally came into the purview of Guo Ziyi, the highest official in the Hezhong region. This development also relates to the extensive official and civilian foundation of the local River God faith. Guo Ziyi hoped to renovate the temples and erect monuments for the River God with the aim of enhancing official–civilian connections and stabilizing social order in the region.

After the temple stele was erected, several representative figures appeared in the inscription: In a certain sense, Cui Yu 崔寓, the magistrate of Hezhong Prefecture, represented the government and Li Kai 李開, who was the county magistrate of Hexi County, was also the specific executor of this project. In addition, there were also representatives of the common people, such as Wang Duan 王端, an old man who was toothless and bald (typically, an elder with a certain prestige represented the mainly public opinion in the Hezhong area). The participation of the literati and writers further helped this event to be disseminated more widely through their writing. The establishment of the temple stele can be regarded as a ceremonial and collaborative endeavor, involving diverse social strata within the local community under official guidance. The River God was jointly revered by various social classes in the Hezhong region, serving as a sacred symbol of the local community. Followers from different social strata shared the same psychological needs, and their collective worship of the River God became a medium for achieving psychological unity among these groups.

From the government’s perspective, the historical tradition of River God worship has led rulers to place great emphasis on the sacrificial ritual and its high degree of unity. This is closely intertwined with endeavors to uphold the hierarchical structure of the feudal system. After the ceremony, there would also be the presentation of some official texts and ideological propaganda, including the erecting of monuments and the writing of eulogies for (for example) Jin Chenggong’s 晉成公 “Da He Fu 大河賦”, Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei’s 北魏孝文帝 “Ji He Wen 祭河文”. Then, in the second year of Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou’s 北周武帝 Tianhe 天和 (567 AD), the powerful minister Yuwen Hu 宇文護 built a monument at the Si Du Temple known as the “Hou Zhou He Du Stele 后周河瀆碑”. There is a record and postscript in Zhao Mingcheng’s 趙明誠 “Jin Shi Lu”金石錄 (Zhao 2009, p. 182), but unfortunately the monument no longer exists. In the first year of the Xiantian 先天 reign of Emperor Xuanzong, and after the sacrifice of Hedu, Cui Yuxi 崔禹錫 was ordered to write “The Rui Song of Hedu in Tongzhou, Tang Dynasty 大唐同州河瀆紀瑞頌” to commemorate the grand scene of this River God sacrifice (Zhao 2009, p. 39). The River God represented the country and only the state could conduct sacrificial ceremonies. The overall and unified Yellow River God was particularly important, for this deity corresponded to the feudal hierarchical system. The official, solemn, and serious sacrifice to the River God reflected the dignity of feudal rulers and the legitimacy of their ruling regime.

From the public perspective, the gradual emergence of worship and faith in river gods can be attributed to the engagement with, and observation of, the historical process of official River God worship. The River God, along with other natural deities, underwent a gradual process of personification, and eventually evolved into a revered deity in folk belief. Through participation in the official river worship ceremony, the belief in the River God was continuously strengthened in the hearts of the people in Hezhong. They not only often paid homage to the place where the River God lived, but even made statues for the relatives of the River God. This method of worship reflects an aspect of the personification of the River God and also proves the strong atmosphere of the River God belief in Hezhong. People aspired to fulfill all the River God’s demands, firmly convinced that any of its unmet desires would precipitate calamity. Consequently, the historical literature frequently documents the sacrifice of the River God and his marriage. Guo Ziyi thus successfully proposed the renovation of a temple and the erection of a monument dedicated to the River God within the area. Naturally, the implementation of this project also signifies Guo Ziyi’s deliberate endeavor to assimilate local belief in the River God into the official belief system. As a representative deity of the national ritual and the Hezhong region, the conducting of the River God ritual required a high degree of consistency and unity, which is closely related to the rulers’ endeavors to uphold the hierarchical order of the feudal system. The renovation of a temple and the erection of a monument or the performance of a series of River God sacrificial ceremonies in the name of national or local officials was aimed at eliminating the complexity and diversity of folk beliefs in River God worship through the exertion of political power. The purpose of this practice was to unify belief in the River God among both governmental authorities and the general populace, thereby reinforcing the hierarchical political structure centered around the emperor. Additionally, it served as an institutionalized framework for venerating river gods within a patriarchal order, with the underlying intention of exerting control over individuals and society.

The renovation of the temple and the erection of a monument also allowed people from all social classes to participate and collaborate in activities, making it a means of regional social integration. Through the collaborative efforts of all parties, a belief space exemplified by the Hedu Temple was established in the Hezhong region. Venerating the River God strengthened the bond between government and civilians, while mitigating local societal conflicts. As the inscription goes, “Eliminating the threat to our nation has strengthened the confidence of our people 安天步於臲卼,定人心於驛騷”. Guo Ziyi utilized this belief system to reinforce the public’s psychological and cultural identification with the Tang Dynasty’s mandate and orthodoxy, while seeking the control and integration of local society in Hezhong. This process helped reestablish the region’s important position and deter potential threats from Hebei vassals and the Tubo, thereby creating crucial barriers with which to defend the two capitals.

Conclusions

At the end of the third year of the Dali era, as he prepared to relocate from Hezhong to Binzhou, Guo Ziyi chose to renovated the temple and erect a monument for the River God at the side of the Pujin Pass in Hexi County. This action can be regarded as predicated on the political stance of the ruling class and held not only profound commemorative significance but was also imbued with potent political propaganda. The temple stele serves as a documentary text of the construction and praises the efficacy of the River God and the achievements of Guo Ziyi, thereby exemplifying the common practice of praising deities and extolling officials’ virtues found in temple stele texts in general. However, it also implies a certain historical particularity.

The An Lushan Rebellion dealt a severe blow to the Tang Dynasty, and, following its suppression, the Tang Dynasty actively implemented a series of political, economic, and societal measures to restore its ruling authority, including the construction of ritual systems. The central government aimed to enhance the communication between humans and deities through ceremonial activities, with the objective of acquiring divine blessings and conveying a notion of authority to the subjects of the realm, thereby reinstating the emperor’s firm governance over the country and his own position in the world of heaven and man. The Tang Dynasty was thus eager to restore suburban sacrificial rituals, demonstrating to the world the orthodoxy and legitimacy of the Li Tang 李唐 royal family (Wu 2006, pp. 112–19) and reshaping the authority of the dynasty. This practice was also implemented in the loyal military governorships of the Tang Dynasty and was ultimately the intention behind Guo Ziyi’s construction of the River God temple stele project in Hezhong.

The reason for Guo Ziyi’s choice of the River God lies in the profound influence exerted by the historical worship of the River God, as well as in the historical memory and reverent emotions evoked by the participation of officials and civilians in common rituals, with their significant impact on the ancient people who worshipped gods and ghosts. As a result, River God worship has the dual attribute of official and folk beliefs.4 It is precisely for this reason that Guo Ziyi strategically erected a monument, employing the cultural symbol of the River God to construct a homogeneous culture between the officials and the public. This endeavor aimed to enhance their collective solidarity and sense of identity, alleviate local social conflicts and contradictions, effectively uphold the prevailing political structure, and produce social order within the region. At a deeper level, Guo Ziyi’s ultimate goal was to reshape and integrate the Hezhong region into a barrier for the Tang Dynasty. The temple stele was situated adjacent to the primary thoroughfare, and through political landscape effects and word-of-mouth transmission among pedestrians, would have created an impression of the Tang army under the protection of the River God. It would thus have had had a deterrent effect on potential rebels, for it created a political atmosphere of “the mandate of heaven standing with the Tang Dynasty 天命在唐”. In this way, it would have strengthened public psychological and cultural identity towards the continuity of the Tang Dynasty’s mandate of heaven and of orthodoxy.

Appendix

Endnotes

- The Hezhong military governorship was instituted in 756, and included seven prefectures. Significantly, there have been many changes in the name and jurisdiction of the Hezhong military governor, so the scope of rule only includes Pu 蒲,Jin 晉,Jiang 绛,Xi 隰,and Ci 慈in 768. See (Ouyang 1975, p. 1838).

- In traditional Chinese culture, the main hall of the ancestral temple is called “temple (Miao 廟)”, and the back hall is called “chamber (Qin 寢)” They are collectively called “Qin miao.” Qin refers to a place in the temple where the gods or ancestral tablets are enshrined, and it is therefore usually regarded as the dwelling of these gods or ancestors.

- Most folk beliefs are based on specific shrines and are inextricably linked to the region. The official concern is about which deities people choose to worship, rather than what they believe about these deities. See (Watson 1993, pp. 80–113).

- Stephan Feuchtwang believes that one of the differences between official religion and folk religion lies in the former’s emphasis on administrative hierarchy, while the latter places more importance on the efficacy of deities. See (Stephan 1977, pp. 581–608). However, the discussion in this article about river god worship reveals a potential combination of both.

References

- Dong, Gao 董誥 (1740–1818). 1983. Quan Tangwen 全唐文 [Complete Prose Works of the Tang Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Mingfeng 干鳴豐. 2005. Gudai hedu chongsizhidu jiexi 古代河瀆崇祀制度解析 [Analysis of the Ancient river god Worship System]. Journal of Southwest University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Science) 西南民族大學學報 (人文社科版) 11: 291–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Jinhua 賈晉華. 2021. Formation of the Traditional Chinese State Ritual System of Sacrifice to Mountain and Water Spirits. Religions 12: 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sangfan 金相范. 2006. Tangdai cimiao zhengce de bianhua—yi cihao cie de yunyong wei zhongxin 唐代祠廟政策的變化——以賜號賜額的運用為中心 [Changes in Tang Dynasty Temple Policies—Centered on the Application of Number and Amount Granting]. In Songshi Yanjiu Luncong 宋史研究論叢 [Collection of Studies on the History of Song Dynasty]. Edited by Jiang Xidong 姜锡东 and Li Huarui 李华瑞. Baoding: Hebei University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Wen 雷聞. 2009. Jiaomiao zhiwai: SuiTang guojia jisi yu zongjiao 郊廟之外: 隋唐國家祭祀與宗教 [Out of the Suburban and Ancestral Temple Rites: State Sacrifices and Religions in the Sui and Tang Dynasties]. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fang 李昉 (925–996). 1966. Wenyuan yinghua 文苑英華 [Finest Blossoms in the Garden of Literature]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xu 劉昫 (888–947). 1975. Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 [Old Tang History]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Duanlin 馬端臨 (1254–1340). 2011. Wenxian Tongkao 文獻通考 [General Literature Examination]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Jianqiang 牛建強. 2011. Mingdai huanghe xiayou de hedao zhili yu heshen xinyang 明代黃河下游的河道治理與河神信仰 [River Management and River God Belief in the Lower Yellow River during the Ming Dynasty]. Journal of Historical Science 史學月刊 9: 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072). 1975. Xin Tangshu 新唐書 [New Tang History]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, Qingsheng 皮慶生. 2008. Songdai Minzhong Cishen Xinyang Yanjiu 宋代民眾祠神信仰研究 [Research on the Belief in Ancestral Gods among the People of the Song Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Luming 仇鹿鳴. 2012. Cong LuoRangbei kan Tangmo weibo de zhengzhi yu shehui 從<羅讓碑>看唐末魏博的政治與社會 [The Political and Social Conditions of the Weibo Region in the Late Tang Dynasty as Reflected in the Inscription on the Luorang Stele]. Journal of Historical Research 曆史研究 2: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Guang 司馬光 (1019–1086). 1956. Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鑒 [Historical Research]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Feuchtwang. 1977. School Temple and City God. In The City in Late Imperial China. Edited by G. W. Skinner. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sue, Takashi 須江隆. 1994. Tousouki ni okeru shibyo no byogaku·fuugao no kashi ni tsuite 唐宋期における祠庙の庙额·封号の下赐について [On the Granting of Festivals and Titles to Ancestral Temples during the Tang and Song Dynasties]. China Society and Culture 9: 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qisun 王芑孫 (1755–1817). 1986. Beibanwen guangli 碑版文廣例 [Examples of tablet inscriptions]. In Shike shiliao xinbian 石刻史料新編 [Historical Materials from Stone Inscriptions, A New Compilation]. Taibei: Xinwenfeng Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Wei 王瑋, and Lachun Wang 王腊春. 2020. The influence of witchcraft culture on ancient Chinese water relations—A case study of the Yellow River Basin. European Journal of Remote Sensing 53: 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuanlin 王元林, and Huizi Ren 任慧子. 2008. Hanghe zhisi yu heci de yanbian 黃河之祀與河祠的演變 [The Sacrifice of the Yellow River and the Changes of River Temples]. Lishi jiaoxue (gaoxiao ban) 歷史教學 (高校版) Journal of History Teaching 4: 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, James L. 1993. Rites or Beliefs? The Construction of A Unified Culture in Late Imperial China. China’s Quest for National Identity. Edited by Lowell Dittmer and Samuel S. Kim. Ithaca: Cornell Univercity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Zheng 魏徵 (580–643). 1973. Suishu 隋書 [Sui History]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Liyu 吳麗娛. 2006. Lizhi Biange Yu Zhongwantang Zhengzhi 禮制變革與中晚唐政治 [Reform of State Rituals and Politics of the Mid and Late Tang]. In Zhongwantang Shehui Yu Zhengzhi Yanjiu 中晚唐社會與政治研究 [Studies on the Society and Politics of the Mid and Late Tang]. Edited by Zhengjian Huang 黃正建. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Yan 夏炎. 2021. Tangdai difang guangfu shuihan qidao yu shuiliziyuan kongzhi—yi quanshen cimiao beike wei zhongxin 唐代地方官府水旱祈禱與水利資源控制——以泉神祠廟碑刻為中心 [Praying for Rain or Sunny Day and Water Resources Control by Local Government in the Tang Dynasty: Focusing on the Stone Inscription at Temple of Spring God]. Shixue jikan 史學集刊 [Journal of Collected Papers of History Studies] 6: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Song 蕭嵩 (?–749). 2000. Datang kaiyuanli 大唐開元禮 [Kaiyuan Ritual of the Great Tang]. Beijing: The Ethnic Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhiqiang 徐自強, and Menglin Wu 吳夢麟. 2002. Gudai shike tonglun 古代石刻通論 [General Theory of Ancient Stone Inscriptions]. Beijing: Forbidden City Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Changchi 葉昌熾 (1849–1917). 2009. Yu Shi 語石 [A Monograph on Inscriptions on Stones]. Shenyang: Liaohai Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Shi 樂史 (930–1007). 2007. Taiping Huanyu Ji 太平寰宇記 [Taiping Universe Record]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Chao 趙超. 2019. Zhongguo gudai shike gailun 中國古代石刻概論 [Introduction to Ancient Chinese Stone Inscription]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Mingcheng 趙明誠 (1081–1129). 2009. Jinshilu 金石錄 [Catalogue of Bronze and Stone Inscriptions]. Jinan: Qilu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Changwen 朱長文 (1039–1098). 1982. Gujin beitie kao 古今碑帖考 [Textual research tablet inscription and rubbing on ancient and modern]. In Shike shiliao Xinbian 石刻史料新編 [Historical Materials from Stone Inscriptions, A New Compilation]. Taibei: Xinwenfeng Press. [Google Scholar]

Originally published by Religions 15:2 (2024, 229), under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.