Did the construction of the Templum Pacis suggest a restitution of Rome’s treasures to the citizens of Rome?

By Dr. Eric Moormann

Professor of Greek and Latin Language and Culture

Radboud University Nijmegen

Abstract

The past is not destroyed by the present but survives in it as a latent force. No phase of history should be treated as irrevocably finished.

E. Wind, Art and Anarchy, 16

Atque et omnibus quae rettuli clarissima quaeque in urbe iam sunt dicata a Vespasiano principe in templo Pacis aliisque operibus uiolentia Neronis in urbem conuecta et in sellariis domus aureae disposita.1

In this contribution I want to assess the specific cultural and propagandistic functions of the Templum Pacis on the basis of its composition, such as architecture, use of material, and art treasures. We will put to the test whether the Templum Pacis can be considered a Flavian reaction to both Nero and his politics and Augustan art and architecture, and consider how the temple’s symbolism relates to wider Flavian politics and imperial ideology. Can we interpret this temple as a symbol of eternal peace bestowed by an archetypal ‘wise emperor’? And does the construction of the Templum Pacis indeed suggest a restitution of Rome’s treasures to the citizens of Rome, as formulated by Pliny (HN 34.84)?

Introduction

When the emperor Tiberius had Lysippos’ Apoxyomenos or Scraper brought from the Baths of Agrippa to his private bedroom in his residence, probably situated on the Palatine, there rose such a fervid protest among the citizens of Rome that the emperor decided to return it to the baths. Apparently, he was deeply impressed by the people’s indignation about the stealing of a public work of art for private pleasure and was forced to remedy his inappropriate deed immediately.2 No such detailed stories about theft from and restitution to the public domain have been transmitted about subsequent emperors in written sources, but the huge art collection of Nero, displayed in the pavilions belonging to his Golden House, can also be considered a set of treasures stolen from public property, regardless of whether this is true or not.3 Pliny tells us that Nero possessed numerous statues, many of which came to the Templum Pacis and other public spaces like the arcades of the Colosseum after the emperor’s death, thus becoming public property in the process.4 Clearly, the accusation is closely connected to Nero’s bad reputation. And, although Pliny does not explicitly say so, this action made the objects some sort of justified spolia taken away from a despised and justly removed emperor, and rightly given back to the citizens and displayed in public spaces. Many of these spolia were housed in the Templum Pacis, making this one of the principal functions of the large monument erected on the Velia by Vespasian after he took power in 69 CE.5 Another metaphoric use of spolia was the opening of Nero’s Golden House properties to the public by installing the Amphitheatrum Flavium in its centre.

If we can believe the written sources, Vespasian was a rustic and military man, acting according to old Roman traditions, and portrayed as a late Republican elderly and experienced citizen rather than as the eternal youth as which the, admittedly younger, Nero had himself represented.6 He could not be accused of having possessed a fine sense or a great zeal for collecting works of arts. For him, assembling precious bronze and marble figures from past and present in a public location with a strong Flavian connotation was a triumphal action, as if they were manubiae or spolia, conquered at the expense of Nero. As a matter of fact, the construction of the complex was financed ex manubiis as was the Colosseum, but we do not have an inscription to substantiate this.7 All these actions can be seen as actions of imperial ideology, creating an abyssal distance from Nero.

Begun by Vespasian in 71 CE as a triumphal remembrance of the reach of power and the ‘pacification’ of Judaea, the Templum Pacis or, as Procopius called it, Ἀγορὰ or Φόρος Εἰρήνης was completed as soon as 75.8 It would be embellished and enlarged during the reign of his second son, Domitian, from 81 onwards: Domitian installed a library as one of the main additions realized by him, so the complex in its final state can be considered a Domitianic project as well. Vespasian wanted to underline that the pax venerated here was a military peace, which had found its culmination in the victory over Judaea and other liminal areas of the empire. In this way he created a peace monument similar to Augustus’ Ara Pacis Augustae, be it on a much grander scale.9 The inventory of the Templum Pacis included real war spoils, viz. the treasures from the Temple of Jerusalem that were put on display in this complex (see below). These exhibits evidently fitted the emperor’s down-to-earth reputation and were self-explanatory. Although there are certainly strong correspondences between the Templum Pacis and the Forum Augustum,10 the complexes differ in concept, for although the Forum also commemorated victories against internal enemies without exhibiting spoils, it served to display the ancestry of the Julii and the con-nection with the uiri illustres of Rome’s glorious past. In the Templum Pacis, the exposition of Neronian treasures met with the urgency to demonstrate internal peace and the restitution of (Augustan) peace and order, whereas ancestry did not play a role.11 The Flavians had to find other ways to justify their imperium and must have sought the means to place themselves at a great distance from Nero.

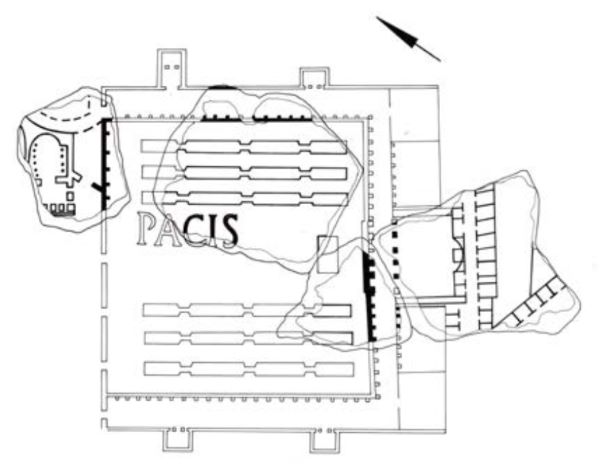

Many new archaeological data on the Templum Pacis have come to light thanks to excavations in the south-eastern part of the complex in 1998–2000, more or less under the modern Via dei Fori Imperiali, in front of the SS. Cosmas and Damian, and at the backsides of the Basilica Aemilia in the Forum Romanum and the Basilica of Constantine on the Velia (figs. 4–5). In the following sections the main elements of this complex will be discussed and interpreted in the light of the main question of this paper, that is, how the temple’s symbolism related to wider Flavian politics and imperial ideology. As a result, one can see parts of the original pavement, the cella, the flight of steps of the south-western portico, and columns belonging to both construction phases (fig. 4).12 The archaeologists of the municipal superintendency have done a good job in visualizing the remains in situ and providing the scholarly world with a rapid stream of publications. This does not exclude critical assessments of the results presented. Recently, the discussion has been given new input by the extensive and extremely detailed publication by Pier Luigi Tucci, who approaches the reconstructions proposed by the Roman archaeologists as a professional architect, in an often harshly critical and caustic as well as verbose treatment, providing lengthy comments on earlier suggestions next to his alternative solutions. It is by no means the purpose of my contribution to provide thorough technical assessments of the data and the interpretations of the Roman archaeologists, let alone a new reconstruction, matters of which I am not capable.13 Yet, we will discuss some of the possibilities offered by various scholars, with a focus on the connections with the existing Augustan and Neronian topography and architecture.

The Topography of the Templum Pacis

The Templum Pacis is situated in the old city centre, amidst crowded living quarters and venerable public spaces (figs.1–2 on p. 133). It covers the northern slope of the Velia, formerly occupied by the Republican Macellum, which was destroyed in the large Neronian fire of 64. It is unlikely that this ruined complex would have remained completely empty until the 70s, unless we take into account the turmoil of 68–69. If we are allowed to assume the presence of still usable remains when the Templum Pacis was built, this would imply that restorations (at least partial ones) had been made to secure a continued use until the Macellum’s demolition in 71.14 The structure of the Macellum, a square peristyle with large open spaces in the middle, might even have influenced the shape of the Templum Pacis. At the north-eastern side, the Templum Pacis was flanked by the Argiletum, the main passage from the Forum Romanum to the Subura, a large and busy space which would become Domitian’s lavishly adorned Forum Transitorium (fig. 2a on p. 133). At the south-western side it was flanked by the Basilica Aemilia in the Forum Romanum and at the north-eastern side by the Subura. In the north-western and south-eastern porticoes there were exedras, one of which is nowadays under the Torre dei Conti.15 Concerning the south-eastern side, it is not clear if the Templum’s back wall stood on the terrain of Nero’s Golden House, the western border of which ran on top of the Velia.16 Large sections of this huge Neronian rus in urbe were now occupied by the Amphitheatrum Flavium and the Baths of Titus.17 All these interventions testify to the erasure of the Neronian urban landscape by the new Flavian urban space. Huge interventions in other areas of the town, especially in the Campus Martius, have obliterated previous buildings, among which Neronian ones, to create a new Flavian Rome.

Functionally and topographically, the Templum Pacis stands apart, since its high-rising enclosure wall fenced the complex off from its surroundings and created a closed character and isolated position, while at the same time forming a huge border area within the densely packed urban space. This might be explained as a means to mark the distinction between the former Neronian private properties and the civic public areas in an act of monumentalization similar to the construction of the Amphitheatrum Flavium, which enabled a damnatio memoriae of Nero through the destruction of his Golden House. Due to this block-like and closed nature, the Templum Pacis did not constitute an enlargement of the Forum Romanum. This is also true functionally, since there are no commodities for commerce and administration integrated into the complex. Neither could the Templum Pacis be seen as an expansion of the Forum Iulium and the Forum Augustum, which commemorated the triumph over old internal enemies of the state and where the grandeur of the two military chiefs in question was at stake. Nevertheless, the religious element is present in all three forums, with temples rising against the back wall of each portico. In this particular instance, its principal function evinces from its name, Templum Pacis; indeed, much more than in the parallel cases and in the imperial fora, its form covers its name in that the complex was an enclosed religious area – (templum; in Greek: τέμενος18), in which an aedes was the focus.

The orientation of the monument, with the main sections at the south-eastern side, has nothing to do with the demands posed by the terrain. The setting might be a mirror image of the Forum Iulium, with the Temple of Venus at the rear end of the north-western side, whereas the Templum Pacis has the actual Temple of Pax also at the rear end, in this case the south-eastern side. Both stood more or less at a square angle with the Temple of Mars Ultor, standing against the rear northern wall of the Forum Augustum. The south-eastern side of the Templum Pacis might have been chosen for this purpose of temple rotation as well, but, more importantly, the south-east was the direction from which Vespasian came to Rome as an emperor. Yet, being within the precinct, many visitors would no longer bother about the orientation. What might be more relevant for them to appreciate the monument is that the best light would fall on this principal side in the afternoon, at the time when most people would have had occasion to stroll through the Templum’s gardens after finishing their duties.

In 192 CE the Templum Pacis burnt down, and under Septimius Severus a reconstruction was created, which was probably completed in 203 CE.19 This included the instalment of the Forma Urbis Romae on the outer wall of the south-eastern hall (nowadays the church of SS. Cosmas and Damian), which might have substituted a predecessor. This wall was the interior, south-western wall of the hall flanking the cella of the shrine of Pax, is now in view from the Via dei Fori Imperiali. We will not discuss this reconstruction, of which the complex of the monastery and church of SS. Cosmas and Damian are the principal remains.20 Yet the Templum Pacis and plan as known from four fragments of the Forma Urbis Romae will form the basis of our reflections, as it must have remained more or less the same (figs. 1–2).

The Templum’s shape (fig. 3) was that of a traditional porticus, a type introduced on the Campus Martius in the third century BCE as the circumference of temples built after military victories; and it became popular over the centuries in variants, another being the Theatre of Pompey on the Campus Martius, which was also full of green spaces, water basins, and works of art.21 Other clear predecessors for this traditional and widely spread form are the ‘Nordmarkt’ in Miletus, the Temple of Zeus Soter in Megalopolis, and the Porticus Vipsania and the Porticus Liviae in Rome.22 All these monuments fulfilled important functions in their environment, but also had an isolated and marked position thanks to their blind, exterior walls. Tucci has worked out the possible connections of the Templum Pacis with antecedents in a much more extensive way and, apart from recalling some of these examples, he deservedly stresses the connection with the Forum Augustum.23 The Templum Pacis itself was a possible source of inspiration for the Library of Hadrian in Athens.24

Let’s cast a glance at the Templum’s shape and building elements. The enclosure measured 135 x 145 m, with the main openings at the north-western side, towards the Argiletum, and subsidiary openings at the north-eastern and south-western sides (figs. 1–3).25 The four-aisled hall circumscribed a large piazza at whose south-eastern side the shrine dedicated to Pax dominated the centre (figs. 2c on p. 133, 4 on p. 137). Its front was the central higher section of the portico, with columns of 50 feet (14.78 m), and at the back of this shrine was the acrolithic statue of Pax, probably a figure of 5 to 7 m, of which a hand seems to have been found, who sat on a 4 m high podium.26 A large altar was erected in front of the shrine.27 At the north and south sides of the aedes double halls were added under Domitian, of which only a part of the south-eastern section has been more or less preserved within the complex of SS. Cosmas and Damian.

A bone of contention is the interpretation of the two sets of three rows of longish rectangular shapes on the Forma Urbis Romae, running from east to west along an open central stretch and the side porticoes (figs. 2b, 5). Most often, it has been argued that these would represent beds of flowers or shrubs, which have also been regarded as representations of ‘botanical imperialism’.28 An alternative would be that they were euripi, channel-shaped water basins like the ones in some large residences in the Vesuvian area.29 Eugenio La Rocca suggested a mix of the two, that is six euripi and a series of ‘rose galliche’ (‘Gallic roses’), of which numerous flower pots were found.30 On the basis of the find of vestiges of the three south-eastern rectangular spaces corresponding with the figures on the Forma Urbis Romae, the excavator Roberto Meneghini argued that they would not have been real basins but marble plateaus with raised borders covered by a permanent layer of water. Like La Rocca, Meneghini and his team reject the idea of gardens, but point at a botanical element in the shape of the ollae foratae or plant pots with holes for drainage. According to them, the remainder of the open area was partly paved with marble plaques and partly covered with gravel or hardened earth (terra battuta).31 Tucci excludes the above-mentioned water installations since according to him they could not be combined with an earth-covered square. The water pipes found seem to have only served to water the plants and/or as drainages. Tucci is so cautious as not to give another proposal and returns to the flower bed option.32 Although it cannot be demonstrated on the basis of the available data, it seems most unlikely that a lavish courtyard like the Templum Pacis would have had parts of the area only ‘covered’ by a mass of sand. I think that we simply have no evidence for this idea, as the area was stripped in later ages, and that the entire space was covered with marble veneer. Stone constructions clad with marble and surrounded by lines of flower pots (with or without ingenious waterworks) would have given a fancier aspect to the otherwise empty space (cf. note 37).

Many statues and other objects (to which I will return shortly) would have stood in the porticoes and on two series of at least five bases flanking the middle stretch leading towards the shrine of Pax.33 If the number of these sculptures was as high as suggested by Pliny, this space seems rather limited. For that reason, one may ask whether the euripi could not have accommodated statues next to the plants,34 in which case the idea of a garden or ‘domesticated’ rural space filled with mythical figures could be suggested. To give a comparable case, the Porticus of Pompey had been a garden filled with many statues.35 What is more, the statues would get more attention standing in a free space, so that they could be admired from all sides.

Architecture and the Impact of Building Materials

There was a certain tradition of material display in public architecture from the late first century BCE onwards. One of the ways in which Augustus’ building politics were characterized was as a metamorphosis of Rome from a town in brick (or maybe tuff as well) into a marble city.36 His Forum Augustum was, much more than that of Julius Caesar, a sea of different types of marble, and in that way a collection of spolia from all parts of the empire, while the Forum Romanum was marmorized as well in an extensive way during his reign.37 Therefore, the fact that Vespasian created a new collection of marble, enlivened by works of art in all kinds of materials (bronze and marble statues, wooden panel paintings, fabric historiae pictae) and greenery, was nothing new. The materials used represented the spheres of the world dominated by Rome, as had been the case with the flooring of the Forum Augustum, but the programme of Templum Pacis was more pointed thanks to the greater stress laid on the materials as expressions of the concept of triumphal geography and display of dominion (see also below). To begin with, red granite columns from Egypt supported porticoes on three sides; some of them would be replaced by higher cipollino columns in its Severan restoration.38 For the construction of the halls lapis Albanus or peperino was used on a large scale,39 comparable to the high back wall of the Forum Augustum, which was meant to protect the structure from the danger of fire in the Subura. The tuff walls of the porticoes and other standing wall structures must have been cladded at the inner sides with marble veneer. The porticoes as well as the cella of the aedes of Pax contained floors in opus sectile in various marbles, which were taken away in late antiquity.40 The excavators could reconstruct circles of 2.54 m in various kinds of marble: pavonazzetto, red porphyry, and granite (fig. 4 on p. 137). As we have seen, the f loor of the courtyard was probably covered with more humble materials, that is nearby local marble, dug in Luni. All these choices may have been made on ideological grounds. The grey tuff material, although largely invisible and adapted on practical grounds as well, referred to ancient building traditions. As to the open square, the visitors were meant to walk on ‘international’ marbles, from foreign, now conquered, areas, as in the Forum Augustum, instead of in the luxurious gardens of Nero’s Golden House.41

To avoid the notion of luxuria in the allegedly sober Flavian programme, it must have been clear from the outset that the marble elements used as a decoration of walls and floors were spolia, probably stemming from Neronian buildings torn down or stripped. The fact that the Templum Pacis was constructed only within four years indeed strongly suggests a large reuse of material as well. The nearest source of large quantities of precious marble was the pavilion of Nero’s Golden House on the adjacent Oppian Hill, still partly in use and partly decorated with fresh and simple white-ground paintings, but for the greater part empty.42 Of course, we cannot prove that the marble here was stripped from floors and walls for this reason, since another occasion to spoil the building would have been the construction of the Baths of Trajan on top of it after 104 CE. But the fact that a number of rooms received a plaster cover in lieu of the marble plaques makes it likely that the spoliation of Neronian marble started as early as 71–72 CE in certain parts of the edif ice and was at least not entirely carried out as late as 104 for the construction of the Baths of Trajan.

Even if the (re-)conquest of Judaea was one of the deeds to be commemorated, the building did not display materials that were specific to that region, such as wood from Lebanon. Yet, most of the golden objects from the Temple in Jerusalem on view may have had their impact as precious curiosities thanks to their religious peculiarities and preciousness, and added a negative value to Nero’s collections. In sum, I would suggest that the material conveyed a clear message of appropriate Flavian soberness in combination with the display of the luxurious Neronian and Judaean material, which now served a higher goal: peace. People entered contrasting realms, on the one hand the pure, old, agricultural Italy and on the other the former extravagance of Nero as well as exoticism from the border areas of the empire.

Art as Monuments of Victory…

Art works or, here, true opera nobilia,43 play a major role in the Templum Pacis. As we can glean from the motto of this paper, Pliny refers to the complex with respect, as an ideal place for the exhibition of statues, in contrast with Nero’s sellaria or private quarters. This need not to be a surprise, since the public servant, military man, and dilettante writer Pliny had a clear Flavian agenda as their public and military servant: he dedicated his magnum opus to Titus, and made special mention of works of art visible in Roman complexes, especially those connected with Vespasian and Titus.44 The same is true for Flavius Josephus, who had taken a reputable intermediary position between his kinsmen and the Roman invaders. For him, the Templum Pacis offered the entire spectrum of world art so that the visitor did not need to go elsewhere to learn more about art history next to appreciating its imperial ideology: πάντα γὰρ εἰς ἐκεῖνον τὸν νεὼ συνήχθη καὶ κατετέθη, δι’ ὦν τὴν θέαν ἄνθρωποι πρότερον περὶ πᾶσαν ἐπλανῶντο τὴν οἰκουμένην, ἕως ἄλλο παρ’ ἄλλοις ἦν κείμενον ἴδεῖν ποθοντες (‘for all objects were brought together and exposed in the temple and to see them people once wandered all over the world [oikoumene], longing to see them while they were lying in various places’).45 Eric Varner def ines the Templum Pacis as ‘a monumental response to integral aspects of the Domus Aurea, intended to instantiate an architectural dialectic between Templum and Domus’.46 He is right to point at the replacement of art works from Nero’s to Vespasian’s construction, and to refer to architectonic similarities.

Neither Pliny nor other sources provide a full catalogue of the works of art on display. As a matter of fact, Pliny’s rare specific references only refer to great artists. In situ, little has been found to fill this lacuna of information. In the area of the library a small bronze bust of Chrysippus, used as segnalibri (bookmarkers), and ivory statuettes of Septimius Severus and Julianus Apostata have come to light, the Severus in the guise of a teacher or philosopher.47 More informative are some statue bases with inscriptions containing the names of famous Athenian sculptors. According to La Rocca these bases belong to the Flavian phase of the Templum Pacis.48 The famous classical artists Naukydes, Myron, Polykleitos, Kephisodotos, Praxiteles, and Leochares were praised by Pliny in his Natural History, but only Leochares appears in both the inscriptions and Pliny. Parthenokles and Boethos as well as the makers of the Gaul statues (Antigonos, Epikouros, Phyromachos, Stratonikos) date from the decades negatively evaluated by Pliny between 296–293; the 121st Olympiad (cessauit ars) and 156–153, the 156th Olympiad (reuixit ars).49 La Rocca argues that this artistic lacuna detected by Pliny referred to bronze work and that the marbles made by Parthenokles – and, I would add, the other ones as well – would probably have met with Pliny’s approval.50

The selection exposed in the Templum Pacis apparently concentrates on remarkable works of art, and most of them are classical or Hellenistic Greek sculptures and paintings; new works51 are rare. We cannot establish a conclusive iconographic programme and the selection criteria employed by Vespasian and his advisors, but will try to determine the connection between the works of arts and their presence in the Templum Pacis as expressions of (military) peace and further imperial ideology. We must assume that many more works were on display, and those we know from these testimonies must have been conspicuous pieces as well. As to Pliny, we observe objects of artists he praises elsewhere, whereas Procopius was especially struck by the lifelike animals by Myron and Pheidias, which Pliny does not even mention. The other literary references (Statius on Pax, Photios on Helena’s Alexander, Pausanias on Naukydes’ wrestler) can be connected with the text’s contexts and barely provide clues to the artistic value of these works. We have an extremely narrow overview of what was exposed in the Templum Pacis. As a consequence, we should remain very circumspect in further interpreting these objects.

But even these disiecta membra are making a statement: it is not very likely that the collection was assembled according to specific ‘art historical’ rules. As a rule, in the Roman tradition of exposing booties the value of a statue as a work of art and, what is more, its provenance from Nero’s Golden House was much more relevant than its artistic quality and value within the history of sculpture. The paintings in the collection belong to the highest achievements of art and formed a category of Greek works that were collected by members of the Roman elite for centuries52: Protogenes, Timantes, and Nikomachos especially receive extensive attention in Pliny’s work. Helena is hailed for the quality of her work, but since female artists are rarely mentioned in Pliny’s and other overviews of artists, Helena’s gender may have played a role in this appreciation as well.

Due to the amazingly wide spectrum of objects collected, there are scholars who ignore specific iconographic programmes. As Paul Zanker has observed: ‘This clearly non-programmatic approach permitted a more open response in contrast to the fora of Augustus and of Trajan and even the Forum Iulium.’53 Tucci has made the same suggestion.54 On the other hand, Steven Rutledge has focused attention on the political impact of public art collections; according to him, the Templum’s artworks were the result of ‘[t]he Restoration of Cultural Property’, regardless of whether they had been stolen previously.55 In her extensive research concerning the ensemble of art works on display in the Templum Pacis, Alessandra Bravi distinguishes three large semantic domains covered by the statuary programme: (1) uirtus and the Roman world, (2) the world beyond the empire as a world without civilization, and (3) the religious realm.56

Although all these suggestions may have hit the mark in some way, I think that we cannot arrive at sound conclusions, mainly because of the scarcity of works listed. Apparently, this was not a systematically formed collection of art works, arranged according to style and artists, but a wild array of diverse objects. The random display of monuments offers the opportunity for the visitor to make their own associations, without being forced to cope with one and the same more or less prescribed Bildprogramm. That vagueness does not mean that some objects could not be connected with a Flavian agenda. This mainly concerned peace, in a Roman context interpreted as the end of physical warfare and the return to flourishing agriculture and economics. A bucolic theme like the Heifer of Myron might have been a good example of that return to the countryside,57 and the same goes for the plants in or around the euripi on the square.

The Jewish spolia have received much scholarly attention, although nothing more specific is known about the components listed by Flavius Josephus, and we have very few depictions of the sacred objects, aside from well-known depictions on the Arch of Titus and some coins.58 The description in Josephus’ Bellum Judaicum included garments of the high priest, vessels, and jewellery, as well as furniture and utensils. Furthermore, there were (a copy of?) the Law and the ‘veil of the Temple’. With Trevor Murphy we may see them as expressions of ‘Triumphal Geography’, known from Pliny’s Natural History’s books on geography; Rutledge aptly speaks of specimens of ‘Displaying Domination’.59

The fact that the historiae pictae shown during the triumph were displayed next to the works of art underlines why these objects were in Rome and, hence, were shown in the Templum Pacis. And what is more, the spoils were a tangible and visible record of the great triumph of 71 CE, which was an ephemeral event that would fade away fairly soon, even if it was fresh in the memory at the time of construction of the Templum Pacis.60 In an excellent study, Taraporewalla has stressed this memory aspect as a means of establishing Vespasian’s auctoritas and maiestas, which he lacked due to his modest ancestry and his military rather than political career.61 In a way, he had to rival the Julio-Claudian consequent appeal to ancient roots, regardless of whether the emperor was good (Augustus) or bad (Nero). As I hope to make clear in this paper, the Templum Pacis formed an ideal instrument to strengthen the first Flavian emperor’s authority and is sound proof of Tarapoweralla’s thesis.

Whereas most spoils from Jerusalem were accommodated in the Templum Pacis, it is an enigma why the Law and Curtains of the Shrine were singled out as private possessions, to be brought to Vespasian’s residence62: was it their more modest appearance, as they were not studded with jewels or made out of gold like the other sacred objects?63

To see the world as settled by the Flavians, the visitor needed some more references to specific loci which had played a role in Flavian taking of power. Rutledge distinguishes three realms as markers of the various ‘worlds’, one more concrete than the other: ‘defeated Judaea, conquering Rome, and Hellenistic culture’.64 He connects a statue of Venus with the oracle of Paphos that had announced bounty to Vespasian during his visit to the sanctuary. Yet, the ancient sources mentioning the visit and used to endorse his theory do not give thought to this association.65 Maybe the traditional, Roman view of Venus or the link with the nearby Forum of Augustus is more likely to explain her presence.66 The Gaul statues by Antigonos, Epigonos (or Isigonos), Phyromachos, and Stratonikos have been interpreted as the original Galates from Pergamon erected within the Pergamene sanctuary of Athena, which date from the early second century BCE, or the Small Gauls from the Acropolis in Athens.67 If so, they would have been transported to Rome at an unknown moment. Here, in the Templum’s context, they would not have functioned as a reference to Pergamon and Asia Minor, but to the submission of the German tribes at the Rhine borders.68 In this way, the Gaul statues in the Templum Pacis (not taken into account by Versluys) complement the mapping of the Flavian empire within the city of Rome. In this case Domitian’s activities could be at stake, since according to Flavius Josephus and Suetonius he served as a young officer in the Rhineland during this period, although it is doubtful whether he really was in this area at all.69

The Alexander painted by Helena from Alexandria would have played a role in this geopolitical aspect as well due to the relation of the topic – Alexander’s defeat of Darius – with the Near East and Egypt, presenting Vespasian as the great military genius who defeated the East, not unlike the Macedonian ruler.70 But because Vespasian was proclaimed the new emperor in Egypt, I think that, indeed, the topographical connection with the Near East and Egypt is extremely relevant to the Templum Pacis, since the area made Vespasian’s ascension to the throne possible and gave a justification to Vespasian to become emperor. The same goes for the large statue of the Nile, with the 16 putti who represent the cubiti of the river. We must recall Pliny’s remark that this statue of the Nile was made of the largest known piece of basanite.71 Taraporewalla observes that, among all works of art in the Templum Pacis, this statue was the only new one, commissioned by the emperor, which gives it extra importance within the set of sculptures.72 Materially, it forms a direct hint at the geographical environment of both Nile and stone, as do the building materials we have briefly analysed before. Versluys has suggested that the Nile statue was important indeed, but that the references made to Egypt in the contemporary Iseum Campense were much more relevant for the Flavians, and that the two complexes might have served as pendants, by means of which power over two complementary parts of the Roman Empire was claimed.73 This is an attractive proposal, which also makes sense when we contemplate the building policy of the Flavian emperors as a whole, as they transformed the town into a Flavian ‘edition’ of Augustan Rome and cancelled that of the hated predecessor Nero.74

… and Encyclopaedia of the World

The encompassing of the whole cosmos within one tangible monument can be seen as one of the major aspects of Vespasian’s and Domitian’s political agenda, which created an encyclopaedic concept that was similar to the written ‘world’ conceived by Pliny in his contemporary Naturalis Historia.75 This universality, which was stressed by Flavius Josephus as well as Pliny, would have been the strongest quality of the Templum Pacis collection.76 The advantage of this project, in contrast to that of Nero’s Golden House, where the (happy few) visitors would have found a similar artistic and mythical encyclopaedia, is that it concerned public mirabilia rather than private luxuria. Thanks to the new Flavian dynasty, all objects together were transformed into a huge anathema for Pax. The broad range of topographical references in the materials used and the provenance of the exposed works ref lect Pliny’s appropriation of the world as subjected to Roman rule.77

Like other scholars, Bravi stresses the all-encompassing qualities that these paintings and sculptures convey as symbols for cultural concepts of Roman society, representing widespread Roman conceptualizations of peace, nature, and human influence in the cultural sphere.78 Art has an edifying quality, not serving as a form of mere divertissement or ornamentation, bringing congruens and aptum back to the people thanks to the established peace.79 For this reason it might be somewhat forced to see in every work of art a reference to Flavian policy. To give some examples, Bravi has proposed that Leochares’ Ganymede personified the favour given by Jupiter to the Flavians, whereas the athletes sculpted by Naukydes and Polykleitos would have symbolized them as victors and shown a touch of uirtus or arête.80 In the first case we may observe that ‘ideal’ nude representations of athletes had come to Rome as originals and were copied by the thousands, becoming emblems of good taste and popular references to Greek culture. Ganymede and Jupiter are solely a mythical couple without political implications; here the opus nobile notion is much more attractive than Bravi’s suggestion presented before. In sum, the quality of the art works as such seems to be what matters, rather than the specific interpretations that have been put forth.81 Meneghini suggests that the choice of artworks indicates that there existed a connection with Athens.82 Yet the sculptures and paintings known from the sources stem from various places and do not betray a specific relationship with the ‘classical’ culture fostered in Athens, which moreover should be avoided in an anti-Neronian way, since Nero had fostered a particular relation with all things Greek.

A peculiar case is Protogenes’ painting of Ialysos: the work was extremely highly praised by Pliny and Plutarch as well as other authors, but we do not know how the man was represented exactly. Apparently, he was the founder of Rhodes and, therefore, of a new dynasty. For Rutledge, this quality would create a link with Vespasian, a view we find back in Tucci’s work.83 By contrast, Bravi connected the pairing of Ialysos and Skylla with victories on land and sea, respectively; in this interpretation Ialysos serves as a mythic huntsman.84 Rutledge’s association is far-fetched and not substantiated by sources, Bravi’s consideration is so generic that it also does not seem very strong as a specification of Flavian qualities. So, it seems better not to speculate too much about a possible specific meaning apart from being an extremely precious work of art. A point unfortunately unsolved as well is the remark made by Plutarch that the painting was destroyed by fire. Since we have no further information about a disaster before the 191 CE fire, we cannot substantiate it, whilst there are post-Plutarch references still full of admiration.85

Library

Domitian added literature as a new element to this polymorph setting. This commodity is known from references in the works of Aulus Gellius, Galenus, and Trebellius Pollio in the Historia Augusta.86 The Templum Pacis’ library became the first public library in Rome after that of Asinius Pollio.87

Some authors argued that its original position cannot be reconstructed.88 As suggested by Colini, and as followed by Meneghini, a candidate might be the hall adjacent to the shrine of Pax, that is, the eastern hall of the two rooms at the south-eastern corner of the Templum Pacis (cf. figs. 2c, 3).89 After the reconstruction in the Severan age, its rear wall was clad with the famous marble Forma Urbis Romae, for which reason this room might have housed the cadastre in combination with the office of the praefectus urbi. If there was a Flavian predecessor of the Forma, as has been assumed in a series of studies on the basis of analogy and even some fragments of older city maps, the Severans continued to use the hall as an administrative building. In the Flavian context, the encyclopaedic character of the library area would have been strengthened by the focus on Rome’s urbanism and on the many interventions made by the Flavians in the urban space, but also by the use of worldwide building materials.90

It has often been thought that this south-western hall (which would be transformed into the Church of SS. Cosmas and Damian) was a Severan addition after the fire of 192,91 but Tucci’s reconstruction, which is complex but sustained by many technical observations, seems very likely (fig. 3). In a lengthy argumentation, he has posited that the first, Vespasianic phase of the Templum Pacis included a large rectangular hall on this spot, accessible from the south-eastern portico.92 During restructuring under Domitian, the wall facing and closing off the Forum Romanum was opened up, and an apsidal hall was added to serve as a library.

The contents of the library are not known, but we may infer the presence of works from Nero’s library or libraries, of which we do not know the contents either, which were transferred for the same reasons as the art works. Elsewhere in Rome, there were large collections of Greek and Roman literature, including scientific literature, especially on medicine. In the case of the Templum Pacis, the inclusion of medical literature has – perhaps unnecessarily – been connected with the existence of a schola medicorum. As told by himself, Galen would teach in this area and lose his library in the fire of 192.93

With the instalment of the library, Domitian followed illustrious predecessors: the library in Asinius Pollio’s Atrium Libertatis and that next to the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine as part of Augustus’ residence.94 Tucci suggests that the library gave shelter to books from other, partly dilapidated commodities, which makes Domitian’s addition to the Templum Pacis a purely practical matter.95 But there might be personal involvement as well, that is, Domitian’s own keen interest in literature. As we know, he organized literary competitions and wrote some works before he became an emperor.96 Domitian’s interest in Greek theatre was expressed by plays given in the new Greekish odeion next to the (also Greek-style) Agon that is now Piazza Navona. In these things he might have imitated and emulated Nero, who was also known for his personal literary ambitions and his interest in Greek culture, but we must not forget that Greek matters had always played a great role in Roman elite culture and that, therefore, the reference to Nero is not so specific at all.

Conclusion

Overall, despite the presence of a conspicuous shrine dedicated to Pax, the Templum Pacis cannot be considered as a purely religious space uniquely focusing on the cult of this abstract goddess. As the other sanctuaries cum foro constructed by Vespasian’s admired predecessors Caesar and Augustus, the Templum Pacis combined the religious aspect with that of a museum dedicated to the all-encompassing Roman fostering of the world, as made possible by Vespasian and his sons. In this way it displayed aspects of otium rather than negotium.97 If we would assume that there was a mix of administration (that of the praefectus urbi), library, and public museum, the latter aspect undoubtedly achieved the greatest impact.98 This stress laid on the public realm constituted a clear contrast with Nero’s former private seclusion. As Meneghini puts it99:

[I]l complesso vespasianeo era infatti un santuario e insieme un luogo di studio e di meditazione oltre che un museo pubblico, secondo un ideale di diffusione della cultura caratteristica dell’epoca e del quale si ritrovano le tracce anche nell’opera di Plinio là dove tesse le lodi di Asinio Pollione, in quanto fondatore della prima biblioteca pubblica nell’Atrium Libertatis, o di Marco Agrippa, come autore di una orazione sulla necessità di rendere i dipinti e le statue di pubblica proprietà.

As a matter of fact, Vespasian’s complex was both a sanctuary and a centre of study and contemplation, next to being a public museum, following an ideal of spreading the culture characteristic of the period, of which we also find traces in Pliny’s work when he hails Asinius Pollio as the founder of the first public library in the Atrium Libertatis, or Marcus Agrippa as the author of a speech on the necessity to make paintings and statues public property.

The Templum’s connection with Augustus is clear from its architectural shape, its architectural ‘quotations’, and artistic furnishings, whereas the link with Nero is defined by the artistic spolia from the Golden House brought to the edifice itself. Vespasian could give a positive twist to the project by the restitution of ‘Nero’s’ treasures to the public. Domitian gave a new turn towards literary activities by adding the large library at the south-eastern corner, and like his father he imitated and emulated the above-mentioned predecessors.

The Templum Pacis, in sum, shows a shift of focus towards the display of artistic treasures. Whereas Nero had collected works of art on account of his luxuria, Vespasian did the same while moved by liberalitas and functioning as a new Agrippa by regaling alleged imperial property to the people100: the objects were taken out from their hiding places within Nero’s private properties and exposed to daylight in the public space of the Templum’s precinct. One may ask whether the visitor was aware of this significant shift; they may have been instructed and ‘helped’ by inscriptions as sources of information. The objects as such are a Sammelsurium, a hotchpotch, not the result of a programmatic collecting activity. Therefore, it is better to refrain from reading too deeply into the specif ic pieces of which we are aware, not only because of their small number, but also due to the way that they were exhibited in the Templum’s grounds. Versluys’ suggestion to see the Templum Pacis and the Iseum Campense as counterparts, displaying Flavian (cultural) policy by covering different areas of the empire, may have played a role as well in the selection of the art works exhibited in these monuments, although not on a systematic and programmatic level as he suggests.

The new data on the Templum Pacis yielded by recent excavations as well as by recent studies have made clear that the complex was no simple old-fashioned porticus like those on the Campus Martius. It combined the traditional elements of these early constructions, including a shrine and collection of spoils, with the notion of political messages on display in the imperial fora next to the Templum’s area. Clearly, Vespasian wanted to build a traditional world of soberness and simplicity, while adopting the increasingly popular display of luxury by using different sorts of marble and exhibiting works of art. The precious spoils from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem were on view next to classical Greek bronze and marble statues. The size of the complex was not modest at all and its position next to venerable loci in town was paramount. The seclusion created by a virtually completely blind outer wall enhanced the suggestive impact of the unique statues. Even if the area was open to the public, the visitor was obliged to cross a marked border before entering this realm of Flavian power and luxuria, which provided illustrations of the superbia of Nero and the liminal inhabitants of the empire like the Jews and the Germans. On the one hand, Augustus is present, most importantly as a source of inspiration for the building, and less through the reference to Pax, which Vespasian could have adopted from the Ara Pacis Augustae.

On the other hand, Nero was unavoidable. Despite attempts to annihilate his memory, he played a much greater role under Vespasian than the emperor probably would have liked, being present in a clear way by virtue of the exposition of his former possessions. The same is true for Domitian, who may have turned things deemed bad into something deemed good by adding a literary dimension, which was as dear to him as it was to Nero.101 In this way he opts for an expansion à la Nero in a complex founded by his father and brother. While the older phase tried to create a certain distance between Flavians and Nero, he recreates a bond with the last Julio-Claudian. In sum, the Templum Pacis is full of this type of tensions and will remain a discussion topic in Flavian studies for a long time to follow.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Plin. HN 34.84: ‘Of all things I have told about, some of the most famous ones in town have already been dedicated by the Emperor Vespasian in the Temple of Peace and in other of his buildings. Nero had violently brought them to Rome and exposed them in the rooms of his Golden House.’

- See Plin. HN 34.62. Briefly mentioned by Miles (2008) 259 and Wellington Gahtan and Pegazzano (2015) 12; Liverani (2015) 73. Liverani (2015) gives a good overview of public collections.

- Miles (2008) 252 shares Nero under the ‘Verrine emperors’ and discusses his thefts (pp. 255–259), criticized precisely because of the exportation of works of art from the public domain. At Delphi alone, he would have stolen 500 statues (Paus. 10.6). Cf. Wellington Gahtan and Pegazzano (2015) 9–15, esp. 14.

- Pliny also mentions two works of which the whereabouts after Nero’s death are not recorded by the encyclopaedist: a bronze Amazon by Strongylion (HN 34.82) and a bronze Alexander the Great that he wanted to be gilded (HN 34 .63).

- Darwall-Smith (1996) 20, 254; Miles (2008) 259–265.

- Our image of Vespasianus in this respect mainly relies on Suet. Vesp. See ultimately various contributions in Coarelli (2009) and Zissos (2016).

- Darwall-Smith (1996) 32.

- Joseph. BJ 158–162, Cass. Dio 66.5.1, Procop. Goth. 8.21.12. See Miles (2008) 263–265.

- See Goldman-Petri (2021) 45–46 for this comparison worked out more extensively.

- Ideologically, see Naas (2002) 438–440; conceptually and architectonically, see, most recently, Tucci (2017) 76–101.

- The recent excavations of parts of the monument hidden under the Via dei Fori Imperiali and immediate surroundings have generated a vast bibliography. I have made use of the following studies (and those mentioned in subsequent notes): Darwall-Smith (1996) 55–68; Coarelli (1999); Köb (2000) 305–324; La Rocca (2001) 195–207; Naas (2002) 440–443; Meneghini and Santangeli Valenzani (2006); Meneghini and Santangeli Valenzani (2007) 61–70; Coarelli (2009) 71–75; various contributions in Coarelli (2009) 158–201; Taraporewalla (2010); Bravi (2009, 2010, 2012, 2014); Rea et al. (2014); Leithoff (2014) 197–205; Meneghini (2015) 49–67; La Rocca, Meneghini, and Parisi Presicce (2015); Tucci (2017).

- In modern cinema, this newly excavated and reconstructed area has achieved a Fellini-like momentum through a brief passage in Paolo Sorrentino’s 2018 f ilm Loro on Silvio Berlusconi’s policy: a huge dustcart tries to avoid killing a passing rat and falls into the hole created by the excavation at the end of the last millennium. It loses its trash, which expands all over Rome and changes into ecstasy pills in a luxurious swimming pool.

- For reviews, see Packer (2018); Moormann (2019); Laurence (2020). In his review, Santangeli Valenzani (2018) is more sceptical, which is understandable due to his involvement in the excavations of the complex and its further investigations. Tucci replied to Packer (2018) (Journal of Roman Archaeology 31 [2018] 722–729) and Santangeli Valenzani (2018) (Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2018.12.39).

- Taraporewalla (2010) 153–154; Scaroina (2015). On the Macellum itself, see LTUR III s.v. Macellum (pp. 201–203); Tucci (2017) 15 (it might have been part of Nero’s Golden House), 19.

- Diebner (2001). On earlier work here, see Colini (1937), who refers to an excavation in 1890 and quotes an old report; also in Tucci (2017) passim. One of the main finds was a marble statue base with a Greek inscription referring to a work by Polykleitos (see Table 5.1 no. 19 on p. 159).

- See Moormann (2018) and Varner (2017).

- Millar (2005); Varner (2017); Moormann (2018).

- See ThesCRA IV, 1–4 (on the Greek temenos); 340–344 (on the Roman templum).

- Cass. Dio 72.24.1–2. On the date of 191 or 192 CE, see Dix and Houston (2006) 692 n. 151 with bibliography. On 203 CE, see Tucci (2017) 349.

- The bibliography on the Forma is vast. I refer to Meneghini and Santangeli Valenzani (2006); Meneghini (2014); De Caprariis (2016) and Tucci (2017) for recent updates.

- On the type, see Gros (1996) 95–120; 38 porticus in Rome are discussed in LTUR I V s.v. Porticus (pp. 116–153). On the porticus of Pompey, see inter alia LTUR IV s.v. Porticus Pompei (pp. 148–150); Miles (2008) 231–237. Ancient evocations of the garden are in Prop. 2.32.12–13; on the works of art, see inter alia Plin. HN 36.41.

- La Rocca (2001) 203–204 f igs. 22–24.

- Tucci (2017) 76–101. The comparison with the Forum Augustum was briefly made earlier by Millar (2005) 110.

- Colini (1937) 36; La Rocca (2001) 203.

- Most recently Tucci (2017) 14. Other dimensions are given as well (e.g. Naas [2002] 441: 110 x 135 m; Millar [2005] 110: 140 x 150 m). Whereas the openings in the Argiletum wall can more or less precisely be reconstructed on the basis of the still partially standing north-eastern wall of the Forum Transitorium, the other sides lack evidence concerning entrances.

- Meneghini (2009) 83–84. As to the cult statue, Meneghini follows Packer (2003) 171–172. For more detail, see Pinna Carboni (2014).

- Tucci (2017) 240–241 suggests that the Cancelleria Reliefs, found near the Cancelleria palace on the Campus Martius, formed the altar’s revetment. They would have been removed, when the recarving of Domitian’s head into that of Nerva after 96 did not have a satisfactory result. This interesting suggestion, however, cannot be substantiated.

- Tellingly expressed in the title of Pollard’s 2009 article: ‘Pliny’s Natural History and the Flavian Templum Pacis: Botanical Imperialism in First Century C.E. Rome’.

- E.g. the longish basin in the grand peristyle of the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, with the many statues exposed, and the similar channel in the garden of the House of Octavius Quartio in Pompeii, referred to in some of the Templum Pacis publications, e.g. Meneghini (2009) 94–95.

- Coarelli (1999); La Rocca (2001) 175–176; cf. Neudecker in Wellington Gahtan and Pegazzano (2015) 130. On the various options, see also Taraporewalla (2010) 151, with bibliography in n. 30.

- Meneghini (2009) 79–81 figs. 83–85; Meneghini and Santangeli Valenzani (2006) fig. 54, reproduced in Tucci (2017) 55 fig. 21.

- Tucci (2017) 58–61.

- Meneghini (2009) 92–93 suggests that the single figures might have stood in the porticoes and the groups – for instance, the defeated Gauls – on the bases along the euripi in the middle of the piazza.

- So Tucci (2017) 60. The suggestion of statues exposed here was already made by Millar (2005) 110 and Corsaro (2014) 325, quoted by Packer (2018) 727 n. 13.

- See the bibliography quoted in n. 20; Rutledge (2012) 154, 222.

- Suet. Aug. 29.

- See most recently the overview of studies in Goldbeck (2015) 17–47.

- For an extensive and critical treatment of this topic, see Tucci (2017) 45–50.

- Tucci (2017) 270–274.

- Meneghini (2009) 83. For Tucci (2017) 37–38 f igs. 13–14 this is not yet proved, since a cocciopest of loor was what the excavators found. See the subsequent suggestions made in the run of the superintendency’s research quoted in Tucci (2017) 420 n. 95. But it is a safe guess to assume the presence of floors in plaques of variously coloured species of marble.

- See how Pliny (HN 36.111) compares farming and utility gardens with luxurious palace and villa gardens. On this passage, see Carey (2003) 103.

- Varner (2017) sees the remains of the Golden House as a ‘dilapidated ruin’, which I think cannot be substantiated, since we know that a couple of interventions in the building were carried out under the Flavians: Meyboom and Moormann (2013) I, 96: rooms 7–16 (almost nothing preserved), 19 (lararium painting), 24, 26, 38, 42, 48, 49, 50, 62, 71, and 116. On the simple paintings, see Esposito and Moormann (2021).

- Hallett (2018) 275, 277–278.

- See Isager (1998) 103 on this passage in the context of the discussion of bronzes (pp. 80–108). See also Naas (2002) 443–446; Neudecker (2018) 150, 157.

- Joseph. BJ 7.160. See inter alia Neudecker (2018) 152. On Flavius Josephus and the Flavian emperors, see Mason (2003); Den Hollander (2014); and Mason (2016), who also mentions briefly the Templum Pacis (pp. 38–39).

- Varner (2017) 252. A similar comparison between Nero and Domitian is made by Isager (1998) 224–229 and Neudecker (2018) 150–152.

- Meneghini (2009) 89–91 figs. 104 (Chrysippos), 105 (Severus); Bravi (2012) 169; Spinola (2014) 165–172 (the first to mention the ivory portrait of Julian Apostata); Tucci (2017) 188 fig. 61 (Chrysippos), 238 fig. 64 (Severus). Spinola mentions a marble bust of Sophokles with the name [Σοφ]όκλης, found in the area of the Villa Rivaldi which might have belonged to the Templum Pacis as well (p. 165).

- La Rocca (2001) 196–200. See in contrast DNO IV no. 1848: on the basis of the letter shapes, the inscriptions might belong to bases erected after the fire of 192 for the statues already there.

- Plin. HN 34.52. See also the following note.

- La Rocca (2001) 196–200. Cf. Isager (1998) 97–98 for a similar explanation and Naas (2002) 99–101 for a critique of snobbism. On the composition of the collection, see Kellum in Friedland, Sobocinski, and Gazda (2015) 426: Shaya (2015) 630–632.

- See above, n. 23.

- See the many cases described in Plin. HN 35, analysed by Isager (1998) 115–122, 135–136.

- Zanker (1997) 187. Also observed by Rutledge (2012) 272 n. 121.

- Tucci (2017) 217–218. He notes that Pliny mentions 150 ancient works of art in diverse locations in Rome, not singling out specifically the Templum Pacis.

- Rutledge (2012) 52. At p. 55 he recalls Vespasian, but he does not refer to the Templum Pacis itself.

- Bravi (2010) 537–546. In particular (1) 537–541, (2) 541–543, (3) 544–546. See also Bravi (2009), (2012) 167–181, (2014) 203–226. The 2012 and 2014 monographs are almost identical apart from the language; in the later Italian version no reference is made to the earlier one, which was presented as a Habilitationsschrift in Heidelberg under the aegis of Tonio Hölscher (see his preface in the 2012 version). Her reconstruction of the position of the objects differs slightly, but this is not explained: cf. Bravi (2012) 168 f ig. 30 with Bravi (2014) 206 f ig. 17.

- Zanker (1997) 188 fig. 18 (marble cinerary urn in the Capitoline Museums showing a cow on a base adorned with garlands as a possible rendering of Myron’s work of art). Cf. Bravi (2012) 179–180; (2014) 219–220: heifer as a symbol of pietas (in virtue of being offered) and rural prosperity. For sources referring to the heifer, see DNO II nos. 751–816, with comment on the statue itself at pp. 84–92.

- Millar (2005); Miles (2008); Rutledge (2012) 123–157 figs. 4.8–9 (Arch of Titus); 275–280.

- Murphy (2004) 128–164, esp. 154–156; Rutledge (2012) 123 (title of Chapter 4). Cf. Östenberg (2009) on the many components of conquest and power on view during the triumphi.

- On the triumph and Josephus’ description, see Beard (2003). Naas (2002) 460–469 analyses Josephus’ description in tandem with Pliny’s passages on art in the Naturalis Historia.

- Tarapoweralla (2010) 146–149. For his career, see Vervaet in Zissos (2016) 43–59.

- Joseph. BJ 7.161–162: ἀνέθηκε δὲ ἐνταῦθα καὶ τὰ ἐκ τοῦ ἱεροῦ τῶν Ἰουδαίων χρυσᾶ κατασκευάσματα σεμνυνόμενος ἐπ’ αὐτοῖς. τὸν δὲ νόμον αὐτῶν καὶ τὰ πορφυρᾶ τοῦ σηκοῦ καταπετάσματα προσέταξεν ἐν τοῖς βασιλείοις ἀποθεμένους φυλάττειν (‘Here he also dedicated the golden vessels from the temple of the Jews, while priding himself on that, but he ordered that their law and the purple curtains of the shrine should be systemized in the palace’). See inter alia Meneghini (2009) 92; Tucci (2017) 225–231. For the realia judaeica, see Yarden (1991). Millar (2005) 169 suggests the palace on the Palatine as the new accommodation of these objects. He rightly asks whether these items were visible for the public as well.63The materiality of the other objects made them precious spoils. Cf. Östenberg (2009) 115.

- Rutledge (2012) 281. For what follows, see pp. 281–283. This leads to what is aptly formulated in Bravi (2010) 537: the Templum Pacis is the oikoumene in a nutshell.

- Rutledge (2012) 281, with reference to Tac. Hist. 2.2–3 (visit of Titus to a Temple of Venus Paphia in Syria). Plin. HN 36.27, also used as a testimony for this suggestion by Rutledge, does not refer to Paphos. On the portents fostered by Vespasian, see Tarapoweralla (2010) 148.

- Bravi (2012) 172: she connects Venus with Pax, as was a practice from Augustus onwards.

- See also Bravi (2014) 224–226 on this statue.

- For the connections of these sculptors with the unknown makers of the lost originals, see the discussions resumed in the various DNO entries quoted in the following. Epigonos’ horn player (tubicen) has been identified as The Dying Gaul in the Capitoline Museums (DNO IV no. 3443), while the Gaulish woman has been associated with the dying Amazon with child in the Archaeological Museum in Naples, originally part of the Athenian Acropolis monument (DNO IV no. 3444).

- A similar change of meaning by a change of context had happened in the 50s BCE, when Caesar erected a monument for his conquest of Gaul by making copies of the same statues in Pergamon (cf. previous note), probably The Dying Gaul in the Capitoline Museums, and the Ludovisi Gaul (depicting a Gaul and his wife committing suicide) in Palazzo Altemps. On these statues as Roman creations (but not connected with Gaul specifically), see, most recently, Ridgway (2018).

- Joseph. BJ 7.76–88; Suet. Dom. 2.1: action undertaken to be not less a good officer than his brother Titus. According to Tac. Hist. 4.86, however, he did not come farther than Lyon (cf. Southern [1997] 20–21). In various contributions in the recent Flavian companion edited by Zissos, this revolt is always ‘settled’ by Petillius Cerialis and Domitian is not recorded at all (Zissos [2016] 66, 151, 212, 213, 219, 264, 284–285). Yet there may have been another occasion in 88, when Domitian’s general L. Antonius pacified Germania superior (Suet. Dom. 6.2). On his overall successful military activities, see Galimberti in Zissos (2016) 97–99; Dart (2016) 212–214. For these statues, see Coarelli (2009) 19 fig. 30; Bravi (2012) 175–178; Bravi (2014) 209–211 (Galates as furor barbaricus). In Bravi ([2012] 168 fig. 30) the Gauls stand in the middle of the area, whereas in her later version of the same study ([2014] 206 fig. 17), they occupy another place.

- Bravi (2012) 173; Bravi (2014) 213–214.

- Plin. HN 36.58. Βασανίτης λίθος is a type of grey wacke. See also Bravi (2012) 171–172; Bravi (2014) 211–213.

- Taraporewalla (2010) 156–157. However, we do not know whether the cult statue of Pax was a new creation or an old work reused in a new context.

- Versluys (2017) 284–285.

- On the Flavian urbanization, see most recently Moormann (2018), with references to further literature. Among the older important studies, see Darwall-Smith (1996); Coarelli (2009).

- Joseph. BJ 7.158–162; Plin. HN 36.101–102. As is common knowledge, the references to the Flavians in the Naturalis History are manifold. See inter alia Isager (1998) 18–23 and Naas (2002) 86–94 on the ‘encyclopédie partisane’. On Pliny’s listing works of art in Rome, see Carey (2003) 79–101; Bounia in Wellington Gahtan and Pegazzano (2015) 81–82.

- Rutledge (2012) 272–284 .

- On Pliny’s ‘Empire in the Encyclopedia’, see Murphy (2004), who uses this expression as his book’s subtitle, as well as Naas (2002) and Carey (2003) 17–40. Murphy’s work does not discuss Pliny’s chapters on art which also have an encyclopaedic flavour, for which see Isager (1998) and Naas (2002), who at pp. 371–393 discusses Rome as the ideal and imperial locus to show the wonders of the world.

- Bravi (2010) 535.

- Bravi (2010) 537. Cf. Joseph. BJ 7 (see above) and Plin. HN 34.84 (quoted at the beginning of this chapter).

- Bravi (2012) 173; Bravi (2014) 220–224.

- There was a high degree of connoisseurship in the Flavian elite. Miles (2008) 265–270 and Wellington Gahtan and Pegazzano (2015) 14–15 discuss some collectors, esp. Nonius Vindex.

- Meneghini (2009) 94. Cf. La Rocca (2001) and Bravi (2009).

- Rutledge (2012); Tucci (2017) 219.

- Bravi (2012) 193–195; Bravi (2014) 216–219. Neither she nor other authors take into account the ship elements carried through Rome in the Triumph of 71, which refer to maritime and other watery victories, which might have got a place in the Templum Pacis as well (see Östenberg [2009] 32).

- See the thorough discussion in Falaschi (2018).

- See extensively Tucci (2017) 174–192.

- Expressively praised for its public status by Plin. HN 35.9–10. On libraries, see Palombi (2014).

- See most recently Dix and Houston (2006) 691–693.

- Colini (1937); Meneghini (2009) 85–90 fig. 102. He suggests the presence of the cadastre here, but we should take for granted that a huge marble plan could not have practical purposes, not giving space for updates due to property changes and building activities. Another function might be the office of the praefectus urbi, all in combination with the library. Here the fragment of large statua loricata came to light (Meneghini [2009] 80–81 fig. 86), compared with the famous Mars in the Capitoline Museums (his f ig. 70), which also might stem from here.

- Darwall-Smith (1996) 64–65: a previous Forma Urbis Romae thanks to fragment 1a, which does not fit well into the Severan plan. It might show the Flavian enlargement of the pomerium. And, we may add, the many projects realized by Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. On the presence of a predecessor, see Miles (2008) 262; Meneghini (2009) 87–88; Tucci (2017) 130–131; Versluys (2017) 284.

- Tucci (2017) 154–153, 374–413. The rotunda, known as Temple of Romulus, would be added as a monumental entrance in the age of Constantine (see pp. 406–407 figs. 159–160). Tucci’s second volume focuses on the complex of the monastery and the church.

- Tucci (2017) 116–125.

- Gell. NA 5.21.9; 16.9.2; SHA Tyr. Trig. 31.10. Cf. Millar (2005) 110–111; Meneghini (2009) 85, esp. n. 21; Tucci (2017) 193–209.

- See the brief discussion of these monuments in Tucci (2017) 176–182.

- Tucci (2017) 191–192.

- See, for example, Coleman (1986); Nauta (2002) 328. I thank Olivier Hekster and Claire Stocks for these references.

- Darwall-Smith (1996) 66–67.

- Meneghini (2009) 94–95.

- Meneghini (2009) 94. It is a matter of debate, however, if the Golden House properties were accessible or not. See Panella (2011) 162–163 and the contribution by Raimondi Cominesi in this volume.

- See Isager (1998) 224–229 and Varner (2017).

- This paper has been written from the focus of the OIKOS research programme ‘Anchoring Innovation’ (see Sluiter [2017]). Anchoring Innovation is the Gravitation Grant research agenda of the Dutch National Research School in Classical Studies, OIKOS. It is financially supported by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (N WO project number 024.003.012; http://www.anchoringinnovation.nl). I thank the following friends for critically reading and improving my text: Nathalie de Haan, Olivier J. Hekster and Stephan T. A. M. Mols (Radboud University), Claire Stocks (University of Newcastle), Miguel John Versluys (Leiden University). Some long discussions with the editors also provoked a number of improvements and clarifications for which I am extremely grateful. Finally, I would like to thank Roberto Meneghini for providing me with his reconstruction drawing of the Templum Pacis (here reworked in fig. 2).

Bibliography

- Beard, M. (2003). The Triumph of Flavius Josephus. In Boyle, A. J. & Dominik, W. J. (Eds.) Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text (pp. 543–558). Brill.

- Boyle, A. J. & Dominik, W. J. (Eds.) (2003). Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text. Brill.

- Bravi, A. (2009). Immagini adeguate: opera d’arte greca nel Templum Pacis. In Coarelli, F. (Ed.) Divus Vespasianus. Il bimillennario dei Flavi (pp. 176–183). Electa.

- Bravi, A. (2010). Angemessene Bilder und praktischer Sinn der Kunst: Griechische Bildwerke im Templum Pacis. In Kramer, N. & Reitz, C. (Eds.) Tradition und Erneuerung. Mediale Strategien in der Zeit der Flavier (pp. 535–551). De Gruyter.

- Bravi, A. (2012). Ornamenta Urbis. Opere d’arte greche negli spazi Romani. Edipuglia.

- Bravi, A. (2014). Griechische Kunst werke im politischen Leben Roms und Konstantinopels. De Gruyter.

- Carey, S. (2003). Pliny’s Catalogue of Culture: Art and Empire in the Natural History. Oxford University Press.

- Coarelli, F. (1999). Pax, Templum. Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, 4, 67–70.

- Coarelli, F. (Ed.) (2009). Divus Vespasianus. Il bimillennario dei Flavi. Electa.

- Coleman, K. M. (1986). The Emperor Domitian and Literature. Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt, 2.32.5, 3087–3115.

- Colini, A. M. (1937). Forum Pacis. Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 65, 7–40.

- Corsaro, A. (2014). La decorazione scultorea e pittorica del templum Pacis. In Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) La biblioteca infinita. i luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico (pp. 317–326). Electa.

- Darwall-Smith, R. H. (1996). Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome. Latomus.

- Dart, C.J. (2016) Frontiers, Security, and Military Policy. In Zissos, A. (E d .) A Companion to the Flavian Age of Imperial Rome (pp. 207-222). Wiley Blackwell.

- De Caprariis, F. (2016). Forma Urbis severiana. Novità e prospettive. Bullettino della Commisione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 117, 77–228.

- Den Hollander, W. (2014). Josephus, the Emperors, and the City of Rome. Brill.

- Diebner, S. (2001). Die nördliche Exedra des Templum pacis und ihre Nutzung während des Faschismus. Bulletin Antieke Beschaving, 76, 193–208.

- Dix, T. K. & Houston, G. W. (2006). Public Libraries in the City of Rome: From the Augustan Age to the Time of Diocletian. Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Antiquité, 118, 671–717.

- DNO. (2014). Der neue Overbeck I-V (S. Kansteiner et al., Eds.). De Gruyter.

- Esposito, D. & Moormann, E. M. (2021). Roman Wall Painting under the Flavians: Continuation or New Developments? In Thomas, R. (Ed.) Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Volume 22: Local Styles or Common Pattern Books in Roman Wall Painting and Mosaics (pp. 33–47). Propylaeum.

- Falaschi, E. (2018). ‘More than Words’: Restaging Protogenes’ Ialysus. In Adornato, G., Bald Romano, I., Cirucci, G. & Poggio, A. (Eds.) Restaging Greek Art works in Roman Times (pp. 173–190). Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto.

- Friedland, E. A., Sobocinski, M. G. & Gazda, E. K. (Eds.) (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Roman Sculpture. Oxford University Press.

- Goldbeck, V. (2015). Fora augusta: das Augustusforums und seine Rezeption im Westen des Imperium Romanum. Schnell & Steiner.

- Goldman-Petri, M. (2021). Domitian and the Augustan Altars. In Marks, R. & Mogetta, M. (Eds.) Domitian’s Rome and the Augustan Legacy (pp. 32–56). University of Michigan Press.

- Gros, P. (1996). L’architecture romaine du début du IIIe siècle av. J.-C. àlaf in du Haut-Empire I. Les monuments publics. Picard Éditeur.

- Hallett, C. (2018). Afterword: The Function of Greek Artworks within Roman Visual Culture. In Adornato, G., Bald Romano, I., Cirucci, G. & Poggio, A. (Eds.) Restaging Greek Art works in Roman Times (pp. 275–287). Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto.

- Isager, J. (1998). Pliny on Art and Society: The Elder Pliny’s Chapters on the History of Art. Routledge.

- Jones, B. W. (1992). The Emperor Domitian. Routledge.

- Keesling, C. E. (2016). Epigraphy of Appropriation: Retrospective Signatures of Greek Sculptors in the Roman World. In Ng, D. Y. & Swetland-Burland, M. (Eds.) Reuse and Renovation in Roman Material Culture: Functions, Aesthetics, Interpretation (pp. 84–111). Cambridge University Press.

- Köb, I. (2000). Rom – ein Stadtzentrum im Wandel: Untersuchungen zur Funktion und Nutzung des Forum Romanum und der Kaiserfora in der Kaiserzeit. Kovac.

- La Rocca, E. (2001). La nuova immagine dei Fori Imperiali. Appunti in margine agli scavi. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung, 108, 171–213.

- La Rocca, E., Meneghini, R. & Parisi Presicce, C. (Eds.) (2015). Il foro di Nerva. Nuovi dati dagli scavi recenti, Scienze dell’Antichità, 21.3.

- Laurence, R. (2020). Review of: Tucci (2017). American Journal of Archaeology, 124.3.

- Leithoff, J. (2014). Macht der Vergangenheit. Zur Erringung, Verstetigung und Ausgestaltung des Principats unter Vespasian, Titus und Domitian. V & R unipress.

- Liverani, P. (2015). The Culture of Collecting in Rome: Between Politics and Administration. In Wellington Gahtan, M. & Pegazzano, D. (Eds.) Museum Archetypes and Collecting in the Ancient World (pp. 72-77). Brill.

- Mason, S. (2003). Flavius Josephus in Flavian Rome: Reading on and between the Lines. In Boyle, A. J. & Dominik, W. J. (Eds.) Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text (pp. 559–589). Brill.

- Mason, S. (2016). A History of the Jewish War, A.D. 66–74. Cambridge University Press.

- Meneghini, R. (2009). I Fori Imperiali e i Mercati di Traiano. Libreria dello Stato, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

- Meneghini, R. (2014). La Forma Urbis severiana. Storia e nuove scoperte. In Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) La biblioteca infinita. i luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico (pp. 327–336). Electa.

- Meneghini, R. (2015). Die Kaiserforen Roms. Philipp von Zabern.

- Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) (2014). La biblioteca infinita. I luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico. Electa.

- Meneghini, R. & Santangeli Valenzani, R. (2006). Formae Urbis Romae. Nuovi frammenti di piante marmoree dallo scavo dei Fori Imperiali. ‘L’Erma’ di Bretschneider.

- Meneghini, R. & Santangeli Valenzani, R. (2007). I fori imperiali. Gli scavi del Comune di Rome (1991–2007). Viviani.

- Meyboom, P. G. P. & Moormann, E. M. (2013). Le decorazioni dipinte e marmoree della Domus Aurea di Nerone a Roma I-II. Peeters.

- Miles, M. M. (2008). Art as Plunder: The Ancient Origins of Debate about Cultural Property. Cambridge University Press.

- Millar, F. (2005). Last Year in Jerusalem: Monuments of the Jewish War in Rome. In Edmondson, J., Mason, S. & Rives, J. (Eds.) Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome (pp. 101–128). Oxford University Press.

- Moormann, E. M. (2018). Domitian’s Remake of Augustan Rome and the Iseum Campense. In Versluys, M. J. (Ed.) The Iseum Campense from the Roman Empire to the Modern Age: Temple – Monument – Lieu de mémoire (pp. 161–177). Edizioni Quasar.

- Moormann, E. M. (2019). Review of: Tucci (2017). Bulletin Antieke Beschaving, 94, 268–269.

- Murphy, T. (2004). Pliny the Elder’s Natural History: The Empire in the Encyclopedia. Oxford University Press.

- Naas, V. (2002). Le projet encyclopédique de Pline l’Ancien. École française de Rome.

- Nauta, R. R. (2002). Poetry for Patrons: Literary Communication in the Age of Domitian. Brill.

- Neudecker, R. (2018). Greek Sanctuaries in Roman Times: Rearranging, Transporting, and Renaming Artworks. In Adornato, G., Bald Romano, I., Cirucci, G. & Poggio, A. (Eds.) Restaging Greek Art works in Roman Times (pp. 147–171). Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto.

- Noreña, C. (2003). Medium and Message in Vespasian’s Templum Pacis. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 48, 25–43.

- Östenberg, I. (2009). Staging the World: Spolia, Captives, and Representations in the Roman Triumphant Procession. Oxford University Press.

- Packer, J. E. (2003). Plurima et Amplissima Opera: Parsing Flavian Rome. In Boyle, A. J. & Dominik, W. J. (Eds.) Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text (pp. 167–198). Brill.

- Packer, J. E. (2018). Review of: Tucci (2017). Journal of Roman Archaeology, 31, 722–729.

- Palombi, D. (2014). Le biblioteche pubbliche a Roma: luoghi, libri, fruitori, pratiche. In Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) La biblioteca infinita. i luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico (pp. 98–118). Electa.

- Panella, C. (2011). La Domus Aurea nella valle del Colosseo e sulle pendici della Velia e del Palatino. In Tomei, M. A. & Rea, R. (Eds.) Nerone. Catalogo della mostra (Roma, 13 aprile–18 settembre 2011) (pp. 160–169). Electa.

- Pinna Caboni, B. (2014). La statua di culto. In Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) La biblioteca infinita. i luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico (pp. 313–316). Electa.

- Pollard, E. A. (2009). Pliny’s Natural History and the Flavian Templum Pacis: Botanical Imperialism in First Century C.E. Rome. Journal of World History, 20.3, 309–338.

- Rea, R. (2014). Il templum Pacis. Un centro di cultura nella Roma imperiale. In Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) La biblioteca infinita. I luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico (pp. 241–342). Electa.

- Ridgway, B. S. (2018). The Ludivisi ‘Suicidal Gaul’ and His Wife: Bronze or Marble Original, Hellenistic or Roman? Journal of Roman Archaeology, 38, 248–258.

- Rutledge, S. H. (2012). Ancient Rome as a Museum: Power, Identity, and the Culture of Collecting. Oxford University Press.

- Santangeli Valenzani, R. (2018). Review of: Tucci (2017). Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 2018.11.05.

- Scaroina, L. (2015). Archeologia e progetto nell’Area del Tempio della Pace. Lo scavo del settore nord-occidentale del Templum Pacis. In La Rocca, E., Meneghini, R. & Parisi Presicce, C. (Eds.) Il foro di Nerva. Nuovi dati dagli scavi recenti, Scienze dell’Antichità, 21.3, 195–217.

- Shaya, J. (2015) Greek Temple Treasures and the Invention of Collecting. In Wellington Gahtan, M. & Pegazzano, D. (Eds.) Museum Archetypes and Collecting in the Ancient World (pp. 24-32). Brill.

- Sluiter, I. (2017). Anchoring Innovation: A Classical Research Agenda. European Review, 25, 20–38.

- Spinola, G. (2014). I ritratti dei poeti, ilosoi, letterati e uomini illustri nelle biblioteche romane. In Meneghini, R. & Rea, R. (Eds.) La biblioteca infinita. i luoghi del sapere nel mondo antico (pp. 155–175). Electa.

- Southern, P. (1997). Domitian: Tragic Tyrant. Routledge.

- Tarapoweralla, R. (2010). The Templum Pacis: Construction of Memory under Vespasian. Acta Classica, 53, 145–163.

- Tucci, P. L. (2017). The Temple of Peace in Rome I-II. Cambridge University Press.

- Varner, E. (2017). Nero’s Memory in Flavian Rome. In Bartsch, S., Freudenburg, K. & Littlewood, C. (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Nero (pp. 237–257). Cambridge University Press.

- Versluys, M. J. (2017). Egypt as Part of the Roman koine: Mnemohistory and the Iseum Campense in Rome. In Nagel, S., Quack, J. F. & Witschel, C. (Eds.) Entangled Worlds: Religious Confluences between East and West in the Roman Empire (pp. 274–293). Mohr Siebeck.

- Wellington Gahtan, M. & Pegazzano, D. (Eds.) (2015). Museum Archetypes and Collecting in the Ancient World. Brill.