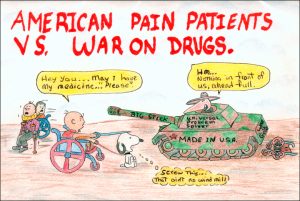

No one can deny that overprescribing and resulting addiction is an enormous problem, but let’s not allow eyebrows to raise at patients in legitimate need of pain relief and treatment. They are easy targets in a lost ‘war’.

By Matthew A. McIntosh / 05.11.2016

Brewminate Editor-in-Chief

Where does it hurt? This question has been asked by doctors or other types of medical practitioners for millennia, and the treatment has been surprisingly similar. Studies of Egyptian scrolls reveal opium being used for the treatment of pain as far back as 1500 BCE. Morphine was introduced in the early 1800s, later followed by the more “non-addictive” (as it was then called) heroin. Opium in its purest form was banned from manufacture or sale in the United States in 1900, after which pharmaceutical companies began creating synthetic “opioid” medications that retained opiate derivatives as a base compounded with other substances. Decades of use for the treatment of chronic pain have provided innumerable patients with much-needed relief, but the creation of these medications has not come without problems.

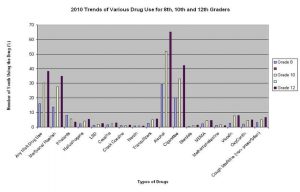

Prescription Drugs Among Teenagers Still Rank Lowest Compared to Illicit Drugs, Alcohol, and Tobacco / National Institute on Drug Abuse, High School and Youth Trends (Click image to enlarge)

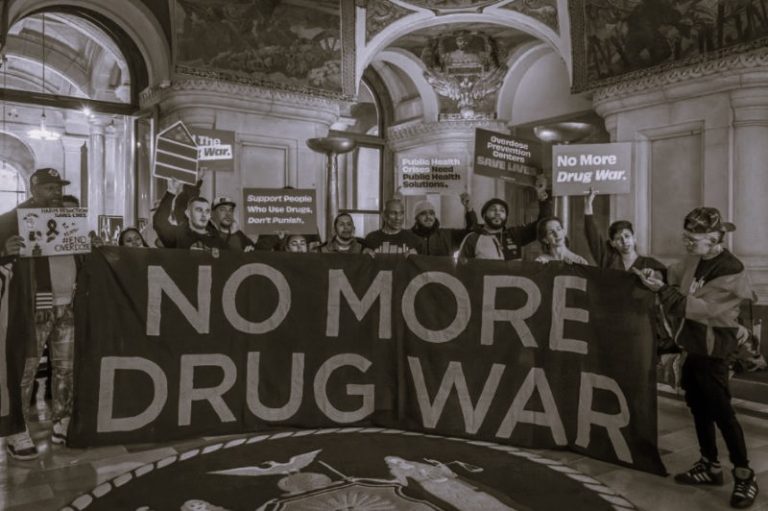

According the National Institute on Drug Abuse, about seven million people were recreational users of psychotherapeutic drugs in 2010, a class of medications including pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants and sedatives (NIH). Because of the abuse of prescription medications, patients and their caregivers find themselves caught between law enforcement authorities and the criminal element they seek to shut down. They say the drug war has both intentionally and unintentionally spread to doctors’ offices and hospitals, leaving in its wake accusations of indiscriminate targeting and a seemingly determined effort to combat drug abuse while attempting to avoid harming the innocent.

Prescription drug abuse has steadily risen in recent years. One of the reasons given for this has been the historical ease of access to them. The NIH reports that prescriptions for opioid pain medications rose from 45 million in 1991 to 209.5 million in 2010 and that overdose deaths from the use of opioids has quadrupled since 1999, now exceeding those attributed to heroin and cocaine combined (NIH). As abuse of opioid pain medications has increased, so too have the associated risks.

Unintentional overdoses have increased because people often do not consider that consuming alcohol increases the respiratory sedative effects of opiates. Users who crush extended released pills to manipulate the formula for an immediate release expose themselves to transmission of HIV and other diseases when sharing needles to inject the medication. But the most obvious and highest incident is that of addiction. Opiates act on the same receptors in the brain as heroin and are equally as highly addictive (NIH). Law enforcement agencies and medical authorities have struggled to determine the cause of these astronomical increases, and opinions have coalesced around two primary contributing factors.

First, the general public has developed a false sense of safety about these medications. If they are prescribed by a physician, the assumption has been that concerns about their safety should be minimal to nonexistent. However, the decision to take these medications does not come without consequences. Anna D. Drakontides, Professor Emeritus of Cell Biology and Anatomy at New York Medical College, wrote, “Additional untoward side effects from drugs should not be imposed on a person for whom the original intent was the alleviation of discomfort” (Drakontides 513). All medications have side effects that must be taken into consideration by a patient when deciding upon the best course of treatment. Opiates will unavoidably create physical dependence if taken for extended periods of time, and attempting to abruptly discontinue their use will result in extremely uncomfortable and possibly dangerous withdrawals. This necessitates a tapering schedule for patients who no longer need them. However, many patients have either not been made aware that this dependence that will develop or have been falsely told either that it won’t or that withdrawal will be effortless.

Information over-exposure can be equally as dangerous. Patients may be ill-informed by exposure to news reports and general rumor about the use of opioids to treat pain. They may fear becoming addicted to the medication and instead allow their pain to go untreated. According to Dr. Robert Arnold of the Medical College of Wisconsin, patients who are uneducated about opiate-based pain relievers may fear addiction, fear becoming tolerant to the medication to the point that it will no longer effectively manage their pain, fear toxic side effects, or simply feel that they are presenting too much difficulty for their physician (Arnold). Dr. Howard M. Marmell, a retired Houston-based neurologist, said, “It is vital that patients understand the difference between addiction and dependence. The body’s developing tolerance to narcotics does not mean they are ‘hooked.’ It’s a consequence of taking the medication, but one that can’t be avoided in cases of continued use in treatment of moderate to severe pain” (Marmell). Important for patients to remember is that the vast majority of those treated for chronic pain with opioid pain relievers, while certainly becoming physically dependent, do not become addicted. In fact, the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry reported only three to five percent of those treated for pain with opioids, taking them as prescribed, later had addiction problems (Prater 129).

Second, an environment has developed in which opioid medications have been easily accessed. Before the crackdown by law enforcement in recent years, “pill mills” – clinics with only basic and sometimes substandard amenities that were known to prescribe opioid pain medications to anyone on a cash-only basis – had appeared in every state. Doctors who operated these fronts were viewed by law enforcement as drug dealers with licenses and prescription pads. The Houston Chronicle reported that the DEA was assisted by 14 other local and state agencies in “Operation King of the Pill” in Houston, executing 50 search warrants on establishments believed to be operating in violation of state mandates for pain management clinics effectively running pill mills (Horswell). Those with money and the right connections have had no trouble finding doctors to prescribe what they want.

Law enforcement access to CT drug monitoring data raises privacy concern | The CT Mirror

Those who have become addicted to opioid pain medication often engage in what has become widely known as “doctor-shopping,” or going to several different doctors to obtain multiple prescriptions that they then have filled at different pharmacies. Different pharmacies would not know if a person was receiving similar prescriptions from others, and doctors would not know if a patient was seeing others. Drug dealers recruit a number of people, often homeless, to falsely complain of pain to physicians who will prescribe various opiates. The dealer pays these people and sells the drugs on the street for astronomical profits. In an effort to stem this type of fraud and to give doctors, pharmacists, and law enforcement agencies a monitoring tool to more effectively address and divert prescription drug abuse, many state legislatures began passing laws mandating the creation of databases, known as PMPs (prescription monitoring programs), in which pharmacists must enter prescriptions filled for all controlled substances. All physicians and pharmacists are given access to the database to keep a real-time check on patients who receive opioid pain medications and to check the prescription history of patients seeing a doctor for the first time. According to the Alliance of States with Prescription Monitoring Programs, all fifty states and one territory have passed legislation to create databases with most being currently fully operational (ASPMP).

The monitoring database in Texas is known as PAT – Prescription Access in Texas. An expansion of the Texas Prescription Program was launched in 1982 that provided patient reports in 30 to 45 days, but today authorized users can access the PAT database any day of the year at any time. Pharmacies that dispense Schedules II-V narcotics must enter a prescription into the database with seven days of filling it identifying the specific drug as well as the prescribing physician and the patient to whom it was dispensed (DPS). The database can be accessed by physicians, pharmacists, law enforcement agencies with open investigations, licensing and regulatory boards, and state medical examiners who need to establish cause of death (ASPMP). While pharmacists are required to enter the information when dispensing medication, they and physicians are under no obligation to check the database prior to prescribing and pharmacies are not required to check it prior to dispensing. CVS, for example, provides access to state databases for its pharmacists to enter information, but unless otherwise mandated they strictly prohibit checking the database before filling prescriptions (The News).

How well can such databases be expected to work? A study conducted by the Canadian Drug Safety and Effectiveness Research Network in British Columbia saw a dramatic reduction in prescriptions for opiates and benzodiazepines that were filled inappropriately after the implementation of the PharmNet database. The study noted a 32.8% reduction in inappropriate prescriptions for opiate pain medications, describing “inappropriate” as a prescription filled within seven days of another similar medication for 30 pills or more (Dormuth 1). The study was conducted when the Canadian database was set up for real-time access while those in the United States were not. The database program in Florida, long considered the state with the largest number of pill mills in operation, has been credited with saving numerous lives. In 2009, Florida’s Department of Health recovered an average number of monthly deaths related to prescription drugs to be 147.3. CapitalSoup.com reporter Greg Giordano reported, “In 2011, that number was cut by 19% due to the implementation of the database as well as more stringent prescribing policies implemented by prescribers” (Giordano). Attempts to contact Mr. Giordano to determine the connection between the implementation of the database and the decrease in overdose deaths was unsuccessful.

Creative Commons

Though this technological approach to fight prescription opioid drug abuse has provided beneficial results, advocates for legitimate chronic pain patients claim it has produced unintended consequences. Allegations have been made that such programs intrude on the private patient-doctor relationship and lead to more suffering by those treated for legitimate chronic pain who suddenly find themselves unable to access the medications they legitimately need. Some doctors view such databases as an obstacle to their ability to practice medicine in a manner that allows them to treat chronic pain without undue intrusion (Schierhorn). Patients have historically grown accustomed to HIPAA privacy statutes that protect their information from unauthorized eyes. Their records contain personal information that has only been accessible to those providing continuing treatment or to insurance companies for the purposes of payment, as well as pharmacists who dispense prescribed medications. However, in a landmark case (Whalen v. Roe) upholding the right of even non-health care providers or those directly associated with the patient to access patient prescription records, the United States Supreme Court has ruled that the pervasive manner in which pharmacies are regulated reduces the expectation of privacy (NAMSDL 18). Different states allow different persons and entities to be authorized to access database information. Some argue that law enforcement agencies accessing patient records is not only an invasion of privacy but ineffective. Scott Gottlieb, former deputy commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, said that it is difficult for law enforcement agencies to discriminate legitimate versus illicit use. (Gottlieb).

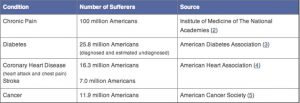

An environment of fear has grown among doctors and pharmacists, leading many to claim under-treatment for moderate to severe pain or no treatment at all in cases in which opioid pain relievers provide the only relief such patients receive. Chronic pain patients are finding themselves either unable to find a new doctor if necessary or being released from current providers who are afraid of popping up on overseers’ radar (Ostrom). Patients may be unjustly accused of doctor-shopping through no fault of their own when required to go to a different pharmacy because their usual one is out of stock or when going to an emergency room or another doctor when their regular doctor is for some reason unavailable. They may be automatically viewed with suspicion, especially new patients, when filling new prescriptions or when being referred to new physicians. This is often the case as many doctors are discharging chronic patients and referring them elsewhere. Stewart B. Leavitt, founding Editor of Pain Treatment Topics at http://pain-topics.org, wrote, “Clearly, the bellwether victims in this ‘war’ are patients with chronic pain whose ongoing access to essential pain relievers has disintegrated or is increasingly threatened” (Leavitt 3).

The November Coalition (november.org)

Whatever one’s opinion, the fact is that prescription drug abuse has become a very real problem resulting in addictions and overdose deaths. Legislatures have attempted through statute to provide law enforcement with tools to combat the problem on the ground and to assist physicians and pharmacists with the means to prevent and divert addiction and fraud when they see it. Though drug dealers and abusers have been the intended target, legitimate patients have been caught in the crossfire and needlessly suffer. But these drugs aren’t going anywhere because their effectiveness in treating moderate to severe pain is the same today as it was in ancient Egypt. Where does it hurt? This age-old question is today followed not necessarily with immediate attempts to alleviate the pain but instead to do so within the confines of new governmental statutes and requirements, efforts that have stemmed the tide of abuse and turned the war on drugs into the war on the easiest target of all – legitimate pain patients and their doctors. They provide easy “winning” statistics for the DEA in a ‘drug war’ that was lost when it began. As patients who can no longer receive the legitimate pain relief they need turn to heroin on the streets, they will be dealt with then as criminals. They are, quite literally, caught between a rock and a hard place in society’s zeal to eliminate a problem without regard to the detriment upon the innocent.

REFERENCES

- Arnold, Dr. Robert. “Why Patients Do Not Take Their Opioids, 2nd Ed.” End of Life/Palliative

Education Resource Center, October 2007, Last Updated April 2009.

< http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_083.htm>.

- ASPMP. Alliance of States with Prescription Monitoring Programs Program Status Map.

<http://www.pmpalliance.org/pdf/pmpstatusmap2012.pdf>. June 13, 2012.

- Dormuth, Colin R. et al. “Effect of a Centralized Prescription Network on Inappropriate

Prescriptions for Opioid Analgesics and Benzodiazepines.” Canadian Medical

Association Journal (September 4, 2012), 1-5.

- DPS. Texas Department of Public Safety Prescription Program Overview.

<http://www.txdps.state.tx.us/RegulatoryServices/prescription_program/index.htm>.

- Drakontides, Anna B. “Drugs to Treat Pain.” The American Journal of Nursing 74:3 (March

1974), 508-513.

- Giordano, Greg. “How the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program is Working Today.”

CapitalSoup.com, October 25, 2012.

- Gottlieb, Scott. “The DEAs War on Pharmacies – and Pain Patients.” Wall Street Journal,

March 22, 2012.

- Horswell, Cindy. “Dozens of health licenses surrendered in pill mill raids.” Houston Chronicle,

November 4, 2012.

- Leavitt, Stewart B. “How the War on Rx-Drugs Victimizes Pain Patients.” Pain-Topics.org.

June 20, 2012.

- NAMSDL. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. “Prescription Monitoring Programs,

Pharmacy Records and the Right to Privacy.” PMP Research (October, 28, 2011), 1-34.

- NIH National Health Institute on Drug Abuse. “Prescription Drug Abuse.” Revised December 2011.

< http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/topics-in-brief/prescription-drug-abuse>.

- Ostrom, Carol M. “New pain-management rules leave patients hurting.” The Seattle Times,

< http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2016035307_pain28m.html>, August 29, 2011.

- Prater, Christopher D. “Successful Pain Management for the Recovering Addicted Patient.”

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 4:4 (2002), 125-131.

- Schierhorn, Carolyn. “Washington State’s new drug monitoring program pits safety against

privacy.” TheDO. < http://www.do-online.org/TheDO/?p=84621>. January 30, 2012.

- The News and Observer. “State Prescription Drug Databases Going Underused.”

< http://www.governing.com/news/state/mct-state-prescription-drug-database-

unused.htm>. November 26, 2012.