What began as religious settlements and agrarian protests evolved into a systematic ideology and, eventually, into governments that claimed the name of socialism.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Long Arc of a New Idea

Socialism did not emerge fully formed in the nineteenth century. While the word itself was coined only in the 1820s, the impulse to reorder society around collective ownership, egalitarian principles, and shared labor has deep roots. Early modern Europe witnessed religious and radical experiments in communal life, from the Jesuit Reductions in Paraguay to the Diggers of the English Civil War. These movements were short-lived, but they reflected a restless search for justice in an age of inequality and upheaval.

By the nineteenth century, industrialization produced both new wealth and unprecedented exploitation. Thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels crystallized socialism into a systematic critique of capitalism, transforming scattered utopias into an ideology of historical struggle. Their ideas inspired movements across Europe, culminating in the Paris Commune of 1871, a fleeting but iconic attempt to put theory into practice. Half a century later, the Russian Revolution produced the first enduring socialist government, embedding the language of Marxism into state power. The journey from early modern experiments to the Soviet state reveals both the continuity of communal ideals and the transformation of socialism into a force that reshaped global politics.

Early Modern Experiments: Jesuits and Diggers

The Jesuit Reductions in Paraguay

In the seventeenth century, Jesuit missionaries in South America established settlements known as reducciones, designed to convert and organize the Guaraní people under Christian communal life. Property was held in common, land distributed collectively, and labor managed for the benefit of the entire community.1 Goods were stored in central warehouses and redistributed, creating a system that resembled both a monastery and a proto-socialist commune.

Although the Reductions were authoritarian in structure, overseen by priests, they impressed later European observers. Enlightenment writers like Montesquieu and Voltaire, though critical of Jesuit influence, recognized in them a functioning alternative to feudal or mercantile exploitation.2 The Jesuit experiment foreshadowed socialist themes of collective ownership and resistance to inequality, though framed in religious rather than secular ideology.

The Diggers of the English Civil War

In 1649, amid the upheavals of the English Civil War, a radical group known as the Diggers (or “True Levellers”) attempted to cultivate common land and abolish private property. Led by Gerrard Winstanley, they argued that “the Earth was made a common treasury for all”.3 For a brief moment, they tilled land in Surrey and other sites, proclaiming that property and hierarchy were artificial constraints on Christian liberty.

The Diggers were swiftly suppressed by landowners and state authorities. Yet their vision of agrarian equality, grounded in both scripture and political radicalism, echoed centuries later in socialist rhetoric. They represent one of the first consciously ideological attempts to challenge private property as the foundation of inequality.

Industrialization and the Birth of Socialist Ideology

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, industrial capitalism created new conditions. Factories transformed labor into mechanized exploitation, and urban poverty revealed the human cost of industrial progress. Early socialist thinkers, often labeled “utopian socialists,” proposed schemes for cooperative living. Charles Fourier imagined phalansteries, self-sustaining communities of cooperative labor. Robert Owen experimented with factory reforms in New Lanark and established New Harmony in America. Henri de Saint-Simon envisioned technocratic elites guiding society for the common good.4

These early experiments were noble but often impractical, criticized by later radicals as well-meaning fantasies. Yet they introduced themes that would become central: the critique of private property, the search for economic equality, and the belief in social planning as an alternative to capitalist chaos.

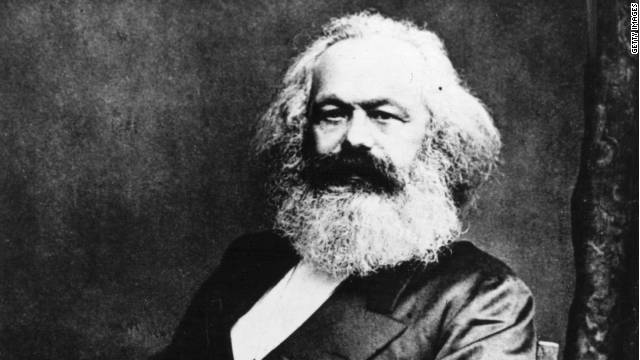

Karl Marx and the Scientific Turn

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels transformed socialism from utopia into what they called “scientific socialism.” In The Communist Manifesto (1848), they declared that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”.5 For Marx, socialism was not merely a dream of equality but the necessary outcome of capitalism’s internal contradictions.

In Das Kapital, Marx analyzed capitalism as a system that extracted surplus value from labor, producing both immense wealth and systemic crises. Engels, in works like Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, drew a sharp distinction between earlier reformist schemes and Marxism’s historical materialism. The working class, organized as a proletariat, was destined to overthrow bourgeois rule and establish collective ownership of the means of production.

What Marx offered was not only a critique of capitalism but also a theory of history. His socialism was both analysis and prophecy, a framework that transformed scattered discontent into revolutionary doctrine.

The Paris Commune of 1871: First Socialist Government

In March 1871, amid the chaos following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, Paris erupted in revolution. Workers, artisans, and radicals seized control of the city and declared the Commune. For seventy-two days, they attempted to create a socialist government: rents were suspended, conscription abolished, factories placed under workers’ control, and officials elected with mandates subject to recall.6

The Commune’s experiments were improvised and inconsistent, but they electrified Europe. Karl Marx hailed it as “the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economic emancipation of labor.”7 Though brutally suppressed by French troops in May 1871, the Commune became a martyrdom in socialist memory, its “red flag” enduring as a symbol of workers’ revolution.

The Russian Revolution and the Soviet State

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 transformed socialism from movement to state power. Led by Lenin, the Bolsheviks seized control in the name of the soviets, workers’ councils, and proclaimed a socialist republic. Land was nationalized, industry placed under state control, and banks absorbed by the government.

While the early Soviet state faced civil war, famine, and foreign intervention, it marked the first enduring attempt to build a society on socialist principles. Marx’s theories were adapted into Leninist practice: a vanguard party would lead the proletariat, and socialism would serve as a transitional stage toward communism.8

The Soviet experiment was both inspiration and warning. To admirers, it proved that socialism could be more than utopia. To critics, it revealed the dangers of centralization and authoritarianism. Yet its significance is undeniable: socialism had moved from religious communes and agrarian radicals to the global stage of modern statecraft.

Conclusion: From Seeds to Systems

The history of socialism from the early modern world to the Soviet state reveals an extraordinary transformation. What began as religious settlements and agrarian protests evolved into a systematic ideology and, eventually, into governments that claimed the name of socialism. The Jesuit Reductions and the Diggers sought to abolish inequality through community. Marx and Engels transformed discontent into doctrine. The Paris Commune tested theory in the crucible of revolution, and the Soviet Union institutionalized socialism as state policy.

The journey underscores the persistence of the human desire for equality, community, and justice. Whether in the fields of seventeenth-century Surrey or the barricades of Paris, the socialist impulse has repeatedly emerged wherever inequality seemed intolerable. By the twentieth century, it had ceased to be an impulse alone. It had become, for better and worse, a governing reality.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ernest J. Burrus, The Jesuit Reductions of Paraguay (St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1986), 45–48.

- Anthony Pagden, The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 215–220.

- Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom in a Platform (London, 1652), 5.

- Gareth Stedman Jones, An End to Poverty? A Historical Debate (London: Profile, 2004), 134–140.

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (London, 1848), 14.

- Robert Tombs, The Paris Commune, 1871 (London: Longman, 1999), 63–69.

- Karl Marx, The Civil War in France (London, 1871), 42.

- Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924 (London: Jonathan Cape, 1996), 475–482.

Bibliography

- Burrus, Ernest J. The Jesuit Reductions of Paraguay. St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1986.

- Figes, Orlando. A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. London: Jonathan Cape, 1996.

- Jones, Gareth Stedman. An End to Poverty? A Historical Debate. London: Profile, 2004.

- Marx, Karl. The Civil War in France. London, 1871.

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. London, 1848.

- Pagden, Anthony. The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Tombs, Robert. The Paris Commune, 1871. London: Longman, 1999.

- Winstanley, Gerrard. The Law of Freedom in a Platform. London, 1652.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.