Homoerotic literature in the medieval world reveals a striking dissonance between moral prescription and artistic expression.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Desire in a World of Boundaries

Medieval literature, far from being monolithic or prudish, contains rich and layered expressions of desire that sometimes slip past the moral boundaries articulated by religious and legal authorities. Among these expressions, homoerotic themes emerge in ways both overt and subtle. From monastic letters and troubadour poetry to Persian ghazals and Arabic love manuals, homoerotic literature in the medieval world occupied a liminal space between the sanctioned and the forbidden.1 Its language was often allegorical, coded, or intertwined with religious devotion, reflecting the constraints of societies in which same-sex acts were frequently condemned, yet same-sex love could be celebrated in art, mysticism, and metaphor.

Understanding this body of literature requires navigating a paradox: the medieval period was one in which theological orthodoxy often stigmatized homoerotic desire, yet literary and artistic production found ways to encode, aestheticize, and even sanctify such impulses. These texts illuminate not only the persistence of same-sex affection but also the inventive strategies of authors and poets who shaped their works to endure within, or just beyond, the limits of orthodoxy.

Christian Europe: Between Allegory and Intimacy

Monastic Affections and the Language of Brotherhood

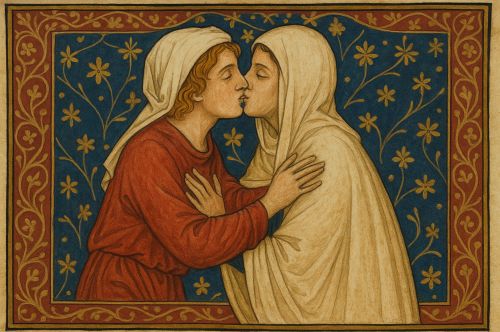

bibles). / Courtesy Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Vienna), Wikimedia Commons

In Christian monastic culture, letters and spiritual treatises frequently used language of intimacy that modern readers might interpret as homoerotic. The writings of Aelred of Rievaulx, for example, extolled spiritual friendship in terms of profound emotional and physical closeness.2 While Aelred rooted his reflections in Augustine’s theology, the affective intensity of his language blurs the line between spiritual kinship and romantic attachment.

Homoerotic subtexts also appear in Latin poetry produced within cathedral schools and monastic scriptoria. The Carmina Burana collection contains love poems addressed explicitly to young men, some playful, others yearning.3 In these works, the eroticism is often overt, even if framed in the learned idiom of classical imitation. The medieval Latin revival of Ovidian verse provided a convenient model for expressing sensuality under the guise of literary tradition.

Courtly Love and Gender Ambiguity

Courtly love literature in the vernacular sometimes entertained same-sex attraction through gender disguise or narrative indirection. In troubadour and trouvère traditions, the persona of the poet could be male or female, and certain songs, especially those of trobairitz, speak with longing toward women in ways that challenge heteronormative assumptions.4 Whether these were expressions of personal desire or literary performance remains a matter of scholarly debate, but their language often operates with a frankness unusual for depictions of same-sex love in Christian Europe.

The Islamic World: Poetics of Beauty and the Beloved

Arabic and Persian Traditions

In medieval Arabic and Persian literature, homoeroticism was often expressed in poetry that idealized the beauty of adolescent boys. This aesthetic, rooted in classical Arabic ghazal tradition, permeated the works of poets such as Abu Nuwas (d. ca. 814), whose verses celebrated wine, youth, and physical desire with an openness that scandalized later commentators.5 While jurists condemned sodomy as a major sin, poets carved out a literary space where homoerotic desire could be acknowledged, stylized, and admired.

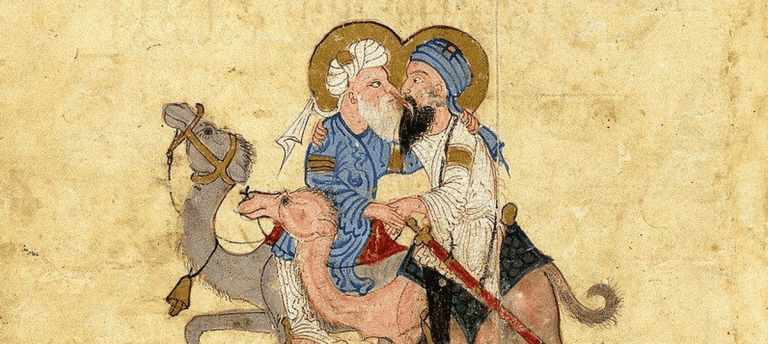

Persian Sufi poetry often transformed homoerotic longing into a metaphor for divine love. Jalal al-Din Rumi’s verses, for instance, describe the beloved, often a male figure, in imagery that oscillates between the spiritual and the sensual.6 This ambiguity allowed such poetry to circulate widely without necessarily being read as erotic in a narrow sense, though contemporaries could appreciate the multiple layers of meaning.

The Adab Tradition and Prose Depictions

Prose literature in the Islamic adab tradition, which combined entertainment with moral instruction, sometimes treated homoerotic themes directly. Collections like al-Jahiz’s Book of Misers or al-Tifashi’s Nuzhat al-Albab include anecdotes, jokes, and erotic tales involving male-male encounters.7 These works demonstrate that homoeroticism was not confined to elite poetic circles but also inhabited the broader landscape of medieval storytelling.

Jewish Contexts: Between Scriptural Prohibition and Cultural Exchange

Medieval Jewish literature engaged homoerotic themes more cautiously, given the prohibitions in Levitical law and rabbinic commentary. Yet Jewish poets in al-Andalus, such as Samuel ibn Naghrillah and Judah Halevi, adopted the Andalusi Arabic poetic forms that frequently featured male beloveds.8 These Hebrew poems sometimes reproduced the aesthetic conventions of Arabic homoerotic verse, even as they situated their imagery within a monotheistic moral framework.

In some cases, homoeroticism entered Jewish texts through translation and adaptation. The transmission of Greco-Arabic medical and philosophical works into Hebrew occasionally preserved anecdotes or metaphors with homoerotic overtones. This literary borrowing underscores the permeability of cultural boundaries in the medieval Mediterranean.

Codes, Metaphors, and Survival: Allegory as Protection

The survival of homoerotic literature in the medieval world often depended on the strategic use of allegory and metaphor. Christian poets could encode same-sex desire in the language of spiritual friendship or Marian devotion. Muslim poets might couch erotic praise in mystical allegory, while Jewish poets in Islamic lands could adopt the courtly forms of their neighbors while avoiding explicit reference to prohibited acts.

Such strategies were not merely evasive; they enriched the texture of the works. By layering meanings, authors invited multiple readings, allowing their texts to resonate differently with diverse audiences. This multiplicity makes medieval homoerotic literature a rich field for historical and literary analysis, as it reflects both the constraints and the creative possibilities of its time.

Conclusion: Desire Across the Boundaries of Time

Homoerotic literature in the medieval world reveals a striking dissonance between moral prescription and artistic expression. Across Christian, Islamic, and Jewish contexts, writers found ways to articulate same-sex desire within, alongside, or in defiance of religious norms. These works are not simply historical curiosities; they testify to the enduring human capacity to express intimacy and attraction even under conditions of prohibition.

To read them with sensitivity is to encounter a medieval world that was more emotionally complex, more culturally interconnected, and more imaginatively daring than the caricature of a uniformly repressive age. Such literature continues to challenge modern assumptions about the past, reminding us that desire, like literature itself, often refuses to be contained.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 25–27.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Spiritual Friendship, trans. Mary Eugenia Laker (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1974), 55–58.

- Peter Dronke, Medieval Latin and the Rise of European Love-Lyric (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 146–148.

- Simon Gaunt, Gender and Genre in Medieval French Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 91–94.

- Everett K. Rowson, “The Effeminates of Early Medina,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 111, no. 4 (1991): 671–693.

- Franklin D. Lewis, Rumi: Past and Present, East and West (Oxford: Oneworld, 2007), 188–192.

- Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500–1800 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 44–46.

- Raymond P. Scheindlin, Wine, Women, and Death: Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1986), 67–70.

Bibliography

- Aelred of Rievaulx. Spiritual Friendship. Translated by Mary Eugenia Laker. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1974.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Dronke, Peter. Medieval Latin and the Rise of European Love-Lyric. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965.

- El-Rouayheb, Khaled. Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500–1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Gaunt, Simon. Gender and Genre in Medieval French Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West. Oxford: Oneworld, 2007.

- Rowson, Everett K. “The Effeminates of Early Medina.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 111, no. 4 (1991): 671–693.

- Scheindlin, Raymond P. Wine, Women, and Death: Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1986.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.