Across millennia, the mask has been a tool of power, devotion, fear, and play. From stone visages in Neolithic deserts to carnival silks in Venice.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Mask as Threshold

Masks, as artifacts both material and symbolic, occupy one of the most enduring spaces in human history. From carved stone relics in Neolithic deserts to surgical masks in contemporary cities, they serve as mediators between the visible and invisible, the personal and collective, the sacred and profane. The mask is never neutral; it reveals by concealing, transforming identity while exposing the cultural forces that shape its meaning. To trace the history of masks is not merely to follow their changing forms but to confront the recurrent human impulse to make the face both more than itself and other than itself.

Prehistoric and Neolithic Beginnings

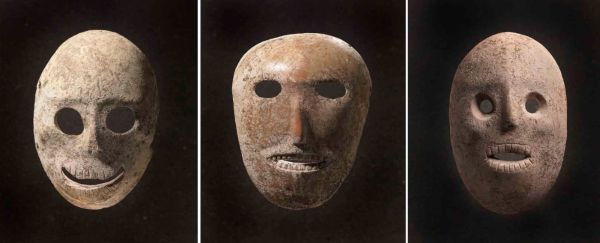

The earliest known masks emerge in the Judean Desert during the 8th to 7th millennia BCE. Carved from stone, these faces with hollow eyes and grim visages suggest an origin in ritual rather than utility.1 They may have served in ancestor worship, materializing the presence of the dead within communal rites, or as intermediaries through which shamans engaged the spiritual world. The mask in this early form was both a tool and a mystery: it demanded performance yet withheld the performer, locating meaning in absence as much as presence.

Simultaneously, across the prehistoric Sahara during the so-called Green Sahara period (c. 6000–4000 BCE), rock engravings depict figures whose heads are exaggerated or concealed beneath animal-like shapes.2 Archaeologists have speculated these were depictions of ritual dancers wearing masks fashioned from organic materials now lost. Here, the mask functioned as a transformative device: the human became animal, the individual became ancestral, the community confronted the otherworldly through embodied performance. Such prehistoric evidence suggests that the mask was not invented but discovered, an extension of a universal impulse to mediate between worlds.

Masks in the Ancient World

Egypt and Nubia

In pharaonic Egypt, the funerary mask emerged as one of the most recognizable artifacts of death. Tutankhamun’s golden mask, fashioned with lapis and glass, exemplifies the belief that preserving the facial identity of the deceased ensured recognition in the afterlife.3 Such masks were not portraits in the modern sense but idealized visages of divinity. By donning them in death, the mortal was transfigured into something eternal.

Neighboring Nubia produced fewer monumental masks but shared with Egypt a concern for death and divine mediation. Archaeological finds suggest the presence of ritual coverings, particularly in elite burials, that linked the deceased with ancestral continuity. These practices echo the prehistoric Saharan use of masking as a channel between living and dead.

Greece and Rome

In Greece, masks became inseparable from the theater. Worn by actors in tragedies and comedies, they exaggerated features and amplified voice, transforming one performer into many characters. Yet their roots lay in Dionysian cult practices, where masks blurred the line between human and god.4 The mask was performance, but performance was worship.

Rome adapted the mask into civic ritual. Patrician households preserved wax imagines, funerary masks of ancestors, which were paraded in processions, ensuring that lineage itself walked with the living.5 In this sense, masks reinforced political authority by binding the present to the weight of ancestral legitimacy.

Mesopotamia and the Levant

Across Mesopotamia, ritual masks represented deities, demons, and protective spirits. Clay and bronze examples suggest their use in temple ceremonies intended to summon or repel divine forces. In the Levant, masks may have played roles in fertility rituals, aligning human reproduction with cosmic cycles. In both settings, the mask’s role was mediatory: to make the invisible visible, or the dangerous containable.

Africa Beyond the Nile

Outside Egypt and Nubia, early African societies nurtured traditions of mask-making that prefigure the elaborate systems of later centuries. Archaeological evidence from early West African cultures reveals ritual use of carved faces, sometimes in wood, sometimes in terracotta, linking participants to ancestral authority and spiritual power.6 The continuity from prehistoric Sahara to ancient Nile to early West African communities marks Africa as a deep cradle of masking traditions, extending across millennia.

Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Death Masks and the Memory of Power

By the Middle Ages, the mask assumed new forms in Europe. Death masks, cast directly from the faces of rulers or thinkers, preserved likeness as political and cultural memory. The mask no longer mediated only with gods or spirits but with posterity. To behold the face of a dead king was to confront the weight of legitimacy, even in absence.

Carnival, Carnival, and Inversion

In Venice and across Europe, the mask became central to carnival. The bauta and moretta masked reveler and courtesan alike, erasing boundaries of class and gender, if only for a season. In carnival the mask inverted society, mocking hierarchies by allowing the powerless to impersonate the powerful. In Commedia dell’Arte, masks fixed archetypes (Harlequin, Pantalone, Columbina) yet gave actors freedom to improvise within them. The mask here both constrained and liberated, binding performer to type while releasing creativity.

Plague and Grotesque Protection

The most infamous mask of this period was the beaked visage of the plague doctor. Designed to hold herbs thought to purify air, its long form became a symbol of dread. Over time it left medicine behind and entered culture as a grotesque reminder of fear itself. Here, function gave way to symbolism; the mask’s original medical purpose became secondary to its cultural afterlife.

Masks in Africa and the Americas

In Africa, traditions such as those of the Dogon and Yoruba developed rich mask cultures that embodied ancestral spirits and cosmic principles. A Yoruba egungun mask did not represent an ancestor but became that ancestor in performance, collapsing representation into embodiment.7 Dogon ritual masks, carved with geometric abstraction, mediated between earth and sky, human and divine. These were not aesthetic artifacts but ontological instruments.

In the Americas, Mesoamerican civilizations produced masks for war, death, and ritual. Aztec turquoise masks combined artistry with religious significance, worn by priests or placed upon the dead. The Maya used masks in funerary rites to secure the journey of rulers into the afterlife. Along the Northwest Coast, transformation masks opened to reveal new faces, dramatizing mythic narratives of shape-shifting and metamorphosis. Across both continents, masks marked the boundary between human and other, history and myth, life and death.

Masks in the Modern World

Modernity did not diminish masks; it multiplied their meanings. In political life, the Guy Fawkes mask, popularized by V for Vendetta, became an emblem of protest, anonymity, and digital-age resistance. The mask here protects but also unites, providing both invisibility and collective identity.

In art, surrealist and avant-garde movements turned to masks to disrupt perception and question identity. Theater in the 20th century, from Brecht to Grotowski, reimagined masks not as concealment but revelation, stripping performance to its elemental form.

Public health reintroduced masks as symbols of fear and solidarity. From the plague doctor to the N95, from SARS to COVID-19, the mask has mediated between protection and politics. During the pandemic, masks became contested objects, signaling trust in science to some, resistance to authority for others. The meaning of the mask, once religious or theatrical, entered the arena of political identity.

In digital culture, masks persist as avatars and filters, shaping how individuals present themselves in a mediated world. The mask here is no longer physical but algorithmic, yet it continues the same ancient work of revealing by concealing.

Conclusion: The Eternal Face of Humanity

Across millennia, the mask has been a tool of power, devotion, fear, and play. From stone visages in Neolithic deserts to carnival silks in Venice, from African ancestors embodied in dance to protestors clad in Guy Fawkes visages, the mask endures as one of the most protean of human artifacts. It conceals only to reveal, reminding us that identity itself is never fixed but always performed.

The history of the mask is thus not a story of hiding but of transformation. It is the history of humanity confronting itself (in death, in ritual, in theater, in protest) through the eternal art of veiling the face to show the soul.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ilan Ben Zion, “Israel Reveals Eerie Collection of Neolithic ‘Spirit’ Masks,” The Times of Israel (2014).

- Augustin F. C. Holl, Saharan Rock Art: Archaeology of Prehistoric Africa (London: Routledge, 2004).

- Nicholas Reeves, The Complete Tutankhamun (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990).

- Richard Seaford, Dionysos (London: Routledge, 2006).

- Harriet I. Flower, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Suzanne Preston Blier, African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

- Henry John Drewal, Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).

Bibliography

- Ben Zion, Ilan. “Israel Reveals Eerie Collection of Neolithic ‘Spirit’ Masks.” The Times of Israel (March 4, 2014).

- Blier, Suzanne Preston. African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Drewal, Henry John. Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

- Flower, Harriet I. Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. Saharan Rock Art: Archaeology of Prehistoric Africa. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Reeves, Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun. London: Thames and Hudson, 2023.

- Seaford, Richard. Dionysos. London: Routledge, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.