Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

A plague doctor was a medical physician who treated victims of the bubonic plague.[1] In times of epidemics, such physicians were specifically hired by towns where the plague had taken hold. Since the city was paying their salary, they treated everyone: both the wealthy and the poor.[2] However, some of the plague doctors were known to charge patients and their families additional fees for special treatments or false cures.[3] Typically they were not professionally trained nor experienced physicians or surgeons; rather they were often either second-rate doctors unable to otherwise run a successful medical practice or young physicians seeking to establish themselves in the industry.[1] These doctors rarely cured their patients; rather, they served to record a count of the number of people contaminated for demographic purposes.

Plague doctors by their covenant treated plague patients and were known as municipal or “community plague doctors”, whereas “general practitioners” were separate doctors and both might be in the same European city or town at the same time.[1][4][5][6] In France and the Netherlands, plague doctors often lacked medical training and were referred to as “empirics”. In one case, a plague doctor had been a fruit salesman before his employment as a physician.[7]

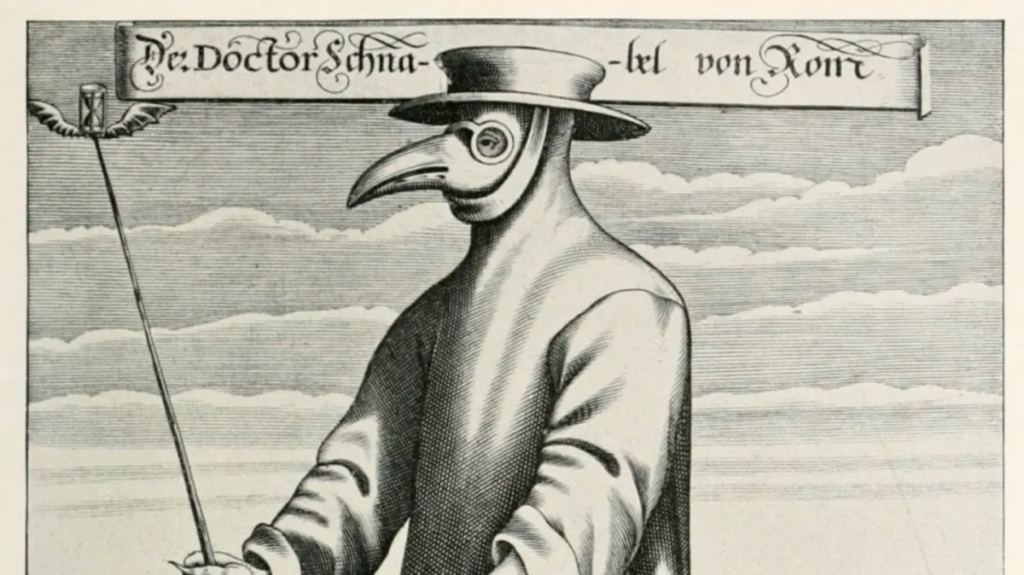

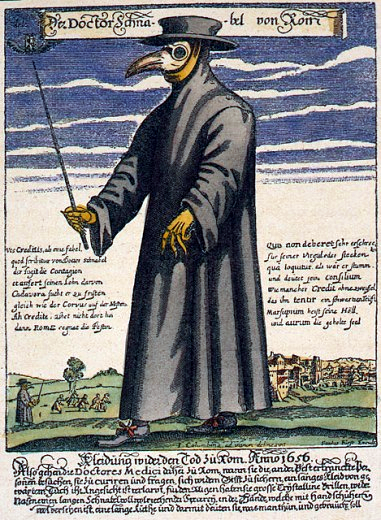

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, some doctors wore a beak-like mask which was filled with aromatic items. The masks were designed to protect them from putrid air, which (according to the miasmatic theory of disease) was seen as the cause of infection. The design of these clothes has been attributed to Charles de Lorme, the chief physician to Louis XIII.[8]

History

The first European epidemic of the bubonic plague dates back to the mid 11th century and is called the Plague of Justinian.[9] The largest plague epidemic was the Black Death in Europe in the 14th century. In times, the large loss of people (due to the bubonic plague) in a town created an economic disaster. Community plague doctors were quite valuable and were given special privileges; for example, plague doctors were freely allowed to perform autopsies, which were otherwise generally forbidden in Medieval Europe, to research a cure for the plague.[10]

In some cases, plague doctors were so valuable that when Barcelona dispatched two to Tortosa in 1650, outlaws captured them en route and demanded a ransom. The city of Barcelona paid for their release.[5] The city of Orvieto hired Matteo fu Angelo in 1348 for four times the normal rate of a doctor of 50-florin per year.[5] Pope Clement VI hired several extra plague doctors during the Black Death plague. They were to attend to the sick people of Avignon. Of 18 doctors in Venice, only one was left by 1348: five had died of the plague, and 12 were missing and may have fled.[11]

Costume

Some plague doctors wore a special costume. The garments were invented by Charles de L’Orme in 1630 and were first used in Naples, but later spread to be used throughout Europe.[12] The protective suit consisted of a light, waxed fabric overcoat, a mask with glass eye openings and a beak shaped nose, typically stuffed with herbs, straw, and spices. Plague doctors would also commonly carry a cane to examine and direct patients without the need to make direct contact with the patient.[13]

The scented materials included juniper berry, ambergris, roses (Rosa), mint (Mentha spicata L.) leaves, camphor, cloves, laudanum, myrrh, and storax.[7] Due to the primitive understanding of disease at the time, it was believed this suit would sufficiently protect the doctor from miasma while tending to patients.[14]

Public Servants

Their principal task, besides taking care of people with the plague, was to record in public records the deaths due to the plague.[7]

In certain European cities like Florence and Perugia, plague doctors were requested to do autopsies to help determine the cause of death and how the plague played a role.[15] Plague doctors became witnesses to numerous wills during times of plague epidemics.[16] Plague doctors also gave advice to their patients about their conduct before death.[17] This advice varied depending on the patient, and after the Middle Ages, the nature of the relationship between doctor and patient was governed by an increasingly complex ethical code.[18][19]

Methods

Plague doctors practiced bloodletting and other remedies such as putting frogs or leeches on the buboes to “rebalance the humors” as a normal routine.[20] Plague doctors could not generally interact with the general public because of the nature of their business and the possibility of spreading the disease; they could also be subject to quarantine.[18]

Notable Renaissance Plague Doctors

A famous plague doctor who gave medical advice about preventive measures which could be used against the plague was Nostradamus.[21][22] Nostradamus’ advice was the removal of infected corpses, getting fresh air, drinking clean water, and drinking a juice preparation of rose hips.[23][24] In Traité des fardemens it shows in Part A Chapter VIII that Nostradamus also recommended not to bleed the patient.[24]

The Italian city of Pavia, in 1479, contracted Giovanni de Ventura as a community plague doctor.[5][25] The Irish physician, Niall Ó Glacáin (c.1563?–1653) earned deep respect in Spain, France and Italy for his bravery in treating numerous people with the plague.[26][27] The French anatomist Ambroise Paré and Swiss iatrochemist Paracelsus were also famous Renaissance plague doctors.[28]

Appendix

Notes

- Cipolla 1977, p. 65.

- Cipolla 1977, p. 68.

- Rosenhek, Jackie (October 2011). “Doctors of the Black Death”. Doctor’s Review. Archived from the original on 2014-05-06. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- Ellis, Oliver C., A History of Fire and Flame 1932 , Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 202.

- Byrne (Daily), p. 169

- Simon, Matthew, Emergent Computation: emphasizing bioinformatics, Publisher シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社, 2005, p. 3.

- Byrne, 170

- “The “Science” Behind Today’s Plague Doctor Clothes”. Gizmodo. June 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- Gordon, Benjamin Lemer, Medieval and Renaissance medicine, Philosophical Library, 1959. p. 471

- Wray, Shona Kelly (2009). Communities and Crisis: Bologna During the Black Death. BRILL.

- Byrne, 168

- Christine M. Boeckl, Images of plague and pestilence: iconography and iconology (Truman State University Press, 2000), pp. 15, 27.

- Byrne (Encyclopedia), p. 505

- Irvine Loudon, Western Medicine: An Illustrated History (Oxford, 2001), p. 189.

- Wray 2009, p. 172.

- Wray 2009, p. 173.

- “The Plague Doctor”. Jhmas.oxfordjournals.org. 2012-04-02. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- Gottfried 1983, p. 126.

- Gottfried 1983, p. 127-128.

- Byfield, Ted, Renaissance: God in Man, A.D. 1300 to 1500: But Amid Its Splendors, Night Falls on Medieval Christianity, Christian History Project, 2010, p. 37

- Hogue, John,Nostradamus: the new revelations, Barnes & Noble Books, 1995, p. 1884

- Smoley, Richard (2006-01-19). The essential Nostradamus: literal translation, historical commentary, and … By Richard Smoley.

- Pickover, Clifford A., Dreaming the Future: the fantastic story of prediction, Prometheus Books, 2001, p. 279.

- “Excellent et moult utile opuscule à tous/ nécessaire qui désirent avoir connoissan/ ce de plusieurs exquises receptes divisé/ en deux parties./ La première traicte de diverses façons/ de fardemens et senteurs pour illustrer et/ embelir la face./ La seconde nous montre la façon et/ manière de faire confitures de plusieurs/ sortes… Nouvellement composé par Maistre/ Michel de NOSTREDAME docteur/ en medecine… by Nostradamus”. Propheties.it. Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- King, Margaret L., Western Civilization: a social and cultural history, Prentice-Hall, 2002, p. 339.

- Stephen, p. 927

- Woods JO (1982). “THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN IRELAND; by J. OLIVER WOODS, MD, FRCGP, Page 40” (PDF). Ulster Med J. 51 (1): 35–45.

- Körner, Christian, Mountain Biodiversity: a global assessment, CRC Press, 2002, p. 13.

References

- Bauer, S. Wise, The Story of the World Activity Book Two: The Middle Ages : From the Fall of Rome to the Rise of the Renaissance, Peace Hill Press, 2003

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick, Daily Life during the Black Death, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick, Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues, ABC-Clio, 2008

- Cipolla, Carlo M. (1977). “The Medieval City”. In Miskimin, Harry A. (ed.). A Plague Doctor. Yale University Press. pp. 65–72

- Fee, Elizabeth, AIDS: the burdens of history, University of California Press, 1988

- Haggard, Howard W., From Medicine Man to Doctor: The Story of the Science of Healing, Courier Dover Publications, 2004

- Gottfried, Robert S. (1983). The Black Death: natural and human disaster in medieval Europe. Simon & Schuster. pp. 126–28.

- Heymann, David L., The World Health Report 2007: a safer future : global public health security in the 21st century, World Health Organization, 2007

- Kenda, Barbara, Aeolian winds and the spirit in Renaissance architecture: Academia Eolia revisited, Taylor & Francis, 2006

- O’Donnell, Terence, History of Life Insurance in its Formative Years, American Conservation Company, 1936

- Pommerville, Jeffrey, Alcamo’s Fundamentals of Microbiology, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2010

- Reading, Mario, The Complete Prophecies of Nostradamus, Sterling Publishing (2009)

- Stuart, David C., Dangerous Garden: the quest for plants to change our lives, Frances Lincoln ltd, 2004

- Wray, Shona Kelly (2 June 2009). Communities and Crisis: Bologna during the Black Death. Brill. p. 312.

- Fitzharris, Lindsey. “Behind the Mask: The Plague Doctor.” The Chirurgeons Apprentice. Web. 6 May 2014.

- Rosenhek, Jackie. “Doctor’s Review: Medicine on the Move.” Doctor’s Review. Web. May 2011.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 03.28.2004, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.