They had a keen interest in commemorating the Persian wars.

By K.W. Arafat

Author and Historian

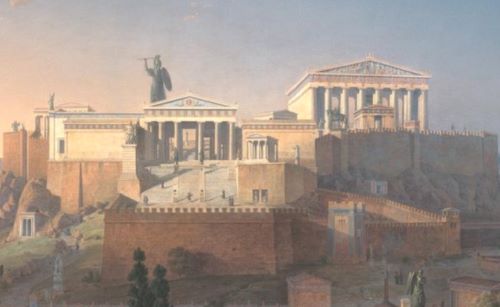

To the ancient visitor approaching the Acropolis,1 a message of victory was sent loud and clear by the parapet on three sides of the temple of Athena Nike. Dated c. 425-20, it consisted of metre-high sculpted panels of the highest quality, featuring figures of winged victories enhanced by paint and bronze attachments shining in the sun.2 The meaning was clear: Victory, Victory, Victory. Here the message is generic, but it has long been advocated that specific battles are shown on the slightly earlier frieze: the south was identified as Marathon by Evelyn Harrison, who also saw the north as representing Plataea.3 I shall not discuss these identifications further here, but I note a comment of Olga Palagia’s, that if a frieze shows Greeks against Persians, it must be a historic event.4 However, apart from problems arising from its state of preservation, I wonder if, so long after the events, the Nike frieze is generic, standing for the Persian wars as a whole, rather than one or more specific battles.

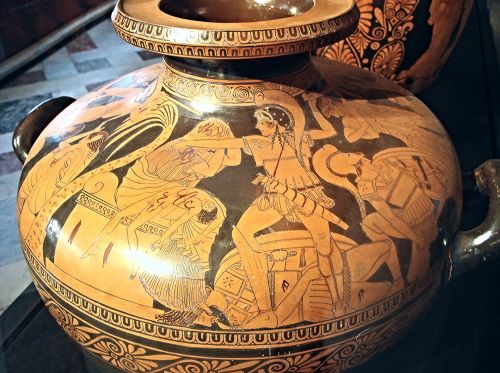

Mythological scenes in sculpture and on vases are commonly interpreted as referring allegorically to real conflict, usually the Persian wars. The locus classicus is the Parthenon metopes, showing Troy, the Amazonomachy, gigantomachy, and centauromachy, which are commonly seen not only as representations of civilization triumphing over barbarity, but also as metaphors for Greeks triumphing over Persians. But there are problems: for example, the Amazons of the west metopes are not certainly Amazons as none is provably female, although this is probably just an accident of survival. Secondly, all these scenes had been used previously without any apparent Persian overtones; and thirdly, if these scenes are relevant to the Persian wars, are they relevant wherever they appear? What of Olympia, for example, where Lapiths and centaurs are the theme of the west pediment? Olympia has no particular link to the Persian wars, and the use of the Elean version of the centauromachy shows that the story reflects local interest if not local pride.5 Interpreting the centaurs as metaphors for the Persians on one building but not another would seem to be unjustifiably selective, a means of reaching a foregone conclusion. Similarly, the gigantomachy had been common since the second quarter of the sixth century and continued to be so throughout the archaic and classical periods.6 By what logic do we pick out a few selected gigantomachy scenes – for example, the east metopes of the Parthenon or the interior of the Parthenos shield – and link them to contemporary military or political events?

I shall return to iconographic trends on pottery later, but still on the Parthenon, the genius behind it, and the whole building programme, was, we are told, Pericles (Plut. Pericles 12-13). But he was associated not with Marathon, but with Salamis – he was the choregos, or sponsor, of Aeschylus’ Persians after all – and with Mycale, the battle at which his father, Xanthippus, fought; indeed Xanthippus’ participation at Mycale was commemorated by a statue of him on the Acropolis (Paus. 1.25.1).

The clearest physical manifestation of Pericles’ interest in commemorating the Persian wars was his Odeion,7 a uniquely striking monument on the south slope of the Acropolis, linked by Pausanias (1.20.4) and other sources (Plut. Pericles 13.6; Vitr. 5.9.1) to the Persian wars. Plutarch and Pausanias say it imitated Xerxes’ tent, or σκηνή, a word which also brings to mind the backdrop used for staging plays in the theatre, appropriately for the choregos of the Persians. One recurrent theme in Persians is hybris, exemplified by the one monument which Pausanias cites as resulting from hybris, in this case that of the Persians. The setting is Rhamnous, a coastal site about ten kilometres from Marathon, where there was a sanctuary of Nemesis ‘who of all deities is most inexorable to the proud. It appears that the barbarians who landed at Marathon incurred the wrath of this goddess; for, lightly deeming it an easy task to capture Athens, they brought with them Parian marble wherewith to make a trophy, as if the victory were already won. Of this very marble Pheidias wrought an image of Nemesis’ (1.33.2-3). Of the thirteen ancient sources for this statue, only three, all epigrams from the Greek Anthology, refer to the Persians and the same story of hybris as Pausanias; the rest are more concerned with the sculptor, named as either Pheidias or Agoracritus of Paros.8 The story not only illustrates the hybris of the Persians and its consequences, but also that it was memorialized conspicuously by a, and perhaps the, leading sculptor of the day. Most significantly, it was a permanent reminder of the victory at Marathon.

This is true also of a far larger, and more conspicuously placed, statue: ‘a bronze image of Athena made from the spoils of the Medes who landed at Marathon. It is a work of Pheidias. The battle of the Lapiths with the centaurs [is depicted] on her shield…. The head of the spear and the crest of the helmet of this Athena are visible to mariners sailing from Sunium to Athens’ (1.28.2, also referred to at 9.4.1). That Sunium is over 40 miles from Athens suggests the size that Pausanias is trying to convey. Of the eleven ancient sources for this statue, referred to by some as the Athena Promachus, only four mention the Persian wars, and only one, apart from Pausanias, refers to Marathon specifically.9 If Pausanias’ sources were ambivalent, he may well have favoured a link with Marathon as appropriate for a colossal statue of Athena.

Salamis does not feature anywhere near as prominently as Marathon in Classical art, but there is one particularly intriguing reference in Pausanias’ account of the temple of Zeus at Olympia, where he saw in the cella a painting of ‘Greece and Salamis holding in her hand the figurehead of a ship’ (5.11.5). The painting was one of several he details on the barriers which kept visitors at a distance from the colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus by Pheidias. He says the paintings are by Panainus, ‘a brother of Pheidias, and the painting of the battle of Marathon in the Painted Stoa at Athens is by him’ (5.11.6). I will return to the Painted Stoa later. It is striking that Salamis should be chosen for depiction at Olympia: maybe it was intended as a complement to the painting of Marathon in Athens, or because the statue of Zeus was created by an Athenian artist, Pheidias, and the personification of Salamis was painted by his brother. Perhaps the linking of these two victories by an Athenian artist suggests they were seen as the two most Athenian victories. Whatever the thinking behind it, the painting takes the unusual form of a personification of Salamis, rather than a depiction of the battle itself as is the case with the Marathon painting. Furthermore, Salamis is depicted next to a personification of Greece, and placed in front of a uniquely large and elaborate statue of Zeus inside the finest temple of its day within a sanctuary of particular resonance to all Greece. In contrast, the Marathon painting is narrative within a secular building in a market-place.

Returning to Athens, I make two further points on the Parthenon: first, on the pre-Periclean Parthenon, which was started after Marathon and destroyed by the Persians in 479. We have no evidence of what it celebrated, if indeed it celebrated anything beyond the city goddess which is, after all, sufficient. It is probable that it was built from the spoils of Marathon, but that does not mean that it celebrated Marathon, that it bore imagery related to Marathon, directly or allegorically. Nonetheless, let us suppose that the pre-Periclean Parthenon celebrated Marathon and was intended to bear architectural sculpture making this clear in some way. How would the Athenians feel when they returned to the Acropolis after the destruction of 479 to find the temple celebrating Marathon destroyed? What would that have said to them about Marathon? That it was a failure? Surely not. But that, if a success, it was a temporary success. And I wonder how perceptions of Marathon changed between the time of the pre-Periclean Parthenon and the Periclean Parthenon. I think of the First World War, seen at the time as ‘the Great War’, ‘the war to end all wars’, until 20 years later there was a second one, and the first was seen more clearly as a failure. The lack of direct representation on the Parthenon of Marathon, or of any battle of Greeks and Persians, contrasts strikingly with the contemporary paintings in the Painted Stoa. That may be due to one being sacred and one secular, but it owes more, I think, to one being inspired by Pericles and the other by Cimon. I do not, though, think that the lack of reference on the Parthenon to Marathon specifically – unless one adheres to John Boardman’s theory that the frieze depicts the heroized dead of Marathon10 – is surprising: permanent success was achieved at Salamis and Plataea, Mycale and Eurymedon. Is that why Aeschylus celebrates Salamis in the Persians and, to a lesser extent, Plataea, rather than Marathon, even though his tombstone singles out his participation at Marathon? Is that why Salamis is personified on Pheidias’ Zeus rather than Marathon?

I have mentioned Pericles several times, and the suggestion that he shied away from celebrating Marathon, preferring instead to emphasize Salamis. It may well be that the main reason for this was the association of Marathon with Cimon, son of Miltiades, the victor of Marathon, and arch-opponent of Pericles who succeeded in having Cimon ostracized in 461. Here two works of Pheidias are relevant: first, the so-called Athena Promachus, mentioned earlier, which was built from the spoils of Marathon, at least according to Pausanias (1.28.2; cf. 9.4.1) and one other of the eleven sources.11 That does not mean, though, that it celebrated Marathon. I make this point because it is often overlooked: for example, Claire Davison says ‘According to Pausanias, [the Athena Promachus] was set up by the Athenians to commemorate Marathon’.12 I re-iterate that Pausanias does not say this, but simply that it was funded by spoils from Marathon.

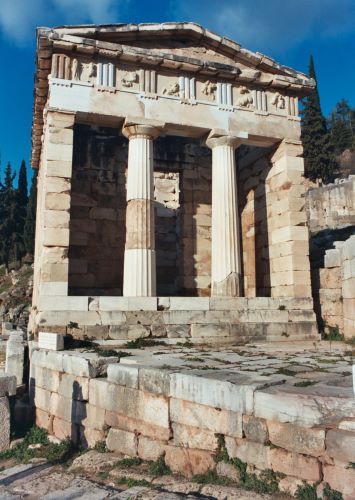

In contrast, Pheidias’ group of bronze statues at Delphi is the only monument we know of which clearly celebrated Marathon as well as being funded by spoils from it. It showed Athena, Apollo, Miltiades, seven Athenian eponymous heroes (appropriately, as the Delphic oracle had chosen them), and three other figures, including Theseus (Paus. 10.10.1-2). I wonder if Pheidias, architect and sculptor to Pericles, was consciously promoting the supreme achievement of Cimon’s father on neutral territory at a safe distance from Athens. The depiction of Miltiades in this statue-group is discussed below. Still at Delphi, Pausanias tells us that the Athenian treasury was funded from the spoils of Marathon. This has been debated at length, mainly on the grounds of the compatibility, or otherwise, of the style of the architectural sculptures.13 Claire Davison has recently revived the suggestion that the freestanding base now placed in front of the Athenian treasury, which refers to a dedication from the first-fruits of Marathon, in fact originally belonged to the eponymous heroes group and was subsequently moved to its current location by the Athenian treasury.14 It is relevant that all Pausanias’ references to treasuries at Delphi are to the reason for their construction: military victory in the cases of those of Athens, Thebes, Syracuse, and possibly Cnidus, the latter three from civil rather than Persian wars; a divine request for a tithe from the gold mines in the case of Siphnus; devotion to the god for Potidaea; no reason is given for the Corinthian. In no case is there a suggestion that anything other than an inscription, or the simple fact of their construction, indicated celebration of a military victory. None of them, as far as we know, has iconography directly reflecting the war that led to its creation.

Since I have referred to the Athenian treasury inscription, I mention what Pausanias (10.13.5) calls the Corinthian treasury and Herodotus (1.14) the treasury of Cypselus: Plutarch (Mor. 400D-E) tells us that the dedicatory inscription on the treasury was changed after the tyranny, at the request of the people, to name the Corinthians rather than the tyrant. We should, therefore, bear in mind that inscriptions on, or in front of, treasuries could change. So, too, could those on freestanding statues: a very relevant example of that is found in Pausanias (1.18.3), who refers to a statue of Miltiades in the Prytaneum at Athens, saying that his name had been changed into that of ‘a Roman’. This is readily paralleled: the statue next to it, of Themistocles, had become ‘a Thracian’, while at the Argive Heraeum, Pausanias says ‘they say that the statue which the inscription declares to be the emperor Augustus is really Orestes’ (2.17.3). What is intriguing here is how Pausanias recognized Miltiades despite his inscription having been erased. This suggests that the image of Miltiades was still very familiar in the second century AD, and constituted an integral part of his prominence for Pausanias.15 This image may have been derived from his appearance on Pheidias’ Marathon monument at Delphi, or conceivably even his depiction on the Painted Stoa.

To return to the Athenian treasury, as noted, even if it were funded from Marathon, that does not mean that it celebrated Marathon, that the metopes with Heracles, Theseus, and the Amazons had a particular reference to Marathon – true, we are told that Theseus had appeared at the battle in support of the Athenians, and Heracles was first recognized as a god by the people of Marathon; and, as Herodotus observes, the Athenian army encamped in the sanctuary of Heracles at Marathon before the battle and subsequently, on returning to Athens to forestall a Persian landing, encamped in another sanctuary of Heracles, at Cynosarges (Hdt. 6.108, 116). But these do not seem to me reasons to interpret the specific Theseus and Heracles depictions on the Athenian treasury differently from the very great number of Theseus and Heracles depictions in Greek art of the time, both sculptural and ceramic.16

The Athenian treasury was prominently placed in the sanctuary, on the sacred way just below the temple of Apollo, and, if the treasury sends out a message of Athenian victory over the Persians, that message was, according to Pausanias, reinforced by the attachment to the architrave of the temple of Apollo of golden shields, some of which he says were dedicated from Marathon (10.19.4), placed at the front of the temple for maximum visibility. These must be votive shields commemorating the battle. Herbert Parke showed that the original shields were replaced after the fire of 373, removed in 340, and replaced again long afterwards with a dedication which simply read ‘the Athenians from the Medes’.17

While such displays of shields on architraves are readily paralleled – for example, Mummius put gilded shields on the temple of Zeus at Olympia (Paus. 5.10.5) – they changed over time as old shields were taken down and new ones put up, as is clear from the east architrave of the Parthenon, where the round weathering from shields is clearly incompatible with the figure of eight Persian shields Alexander captured at the battle of the Granicus in 334 and displayed there (Arrian, Anab. 1.17). What chance, then, that Pausanias actually saw, or could tell if he saw, shields from Marathon? More likely he, or his exegetes, was attracted by the lustre of the name of Marathon and embellished the simple dedicatory inscription ‘the Athenians from the Medes’, and took it to refer to Marathon. That in itself, though, says much about the significance of Marathon even in Pausanias’ time.

We may, therefore, be able to detach both the Athenian treasury and the shields on the Apollo temple from the list of monuments celebrating Marathon.

What of the Athenian stoa built against the retaining wall of the temple of Apollo which Pausanias says commemorates an Athenian victory over the Peloponnesians and their allies in 429 (10.11.6)? Traditionally, it has been believed that Pausanias is mistaken and that the stoa was built to display spoils taken from the Persians in the 470s at Mycale and Sestus, when the Athenians captured the cables of Xerxes’ bridge across the Hellespont.18 But it has also been cogently argued that it in fact was built in the 450s and housed spoils taken from Greek opponents.19 I do not think this issue will be definitively resolved any more than the date of the Athenian treasury will be, but I mention that if the treasury were indeed a Marathon celebration, and if the shields above the stoa on the temple architrave also commemorated Marathon, then we should at least leave open the possibility that the stoa also celebrated Marathon, perhaps in conjunction with other victories over the Persians.

One further piece of evidence from Delphi is relevant, namely Pheidias’ Marathon group of bronze statues mentioned above. It was made from a tithe of the spoils of the battle, as Pausanias tells us twice, giving as his source an inscription (10.10.1-2).What is perhaps most striking is the juxtaposition of the mortal and the immortal, of Miltiades, commander at Marathon, with gods and heroes, within half a century of the battle of Marathon, when it was still a living memory. Pausanias gives some sense of how Miltiades was regarded, at least in the second-century AD: ‘by defeating the barbarians who landed at Marathon and checking the advance of the Persian host, [Miltiades] was the first benefactor of the whole Greek people’ (8.52.1). A further indication that Miltiades’ reputation was high in Pausanias’ day is that the rhetorician and benefactor Herodes Atticus, a younger contemporary of his, claimed direct descent from Miltiades.20 This sense of the primacy of Miltiades in turn indicates the seminal position of the Persian wars, and the battle of Marathon specifically, in Greek perceptions of their own history. It is, therefore, not surprising that there should be a statue of Miltiades at Delphi. There was also one at Athens (1.18.3), albeit with altered inscription as noted.

What is more surprising is that Miltiades’ statue should be placed in the same group as statues of gods and Athenian heroes. But two further passages of Pausanias give further insight into Miltiades’ status: at Olympia, he says of the Sicyonian treasury ‘Here are also deposited other notable things: the sword of Pelops with a golden hilt; the horn of Amalthea, made of ivory, an offering of Miltiades, son of Cimon’ (6.19.6), and he gives the inscription which is his evidence. As in the statue-group at Delphi, Miltiades is juxtaposed with a hero, in this case the eponymous hero of the Peloponnese. His offering is appropriately legendary: the horn of the goat Amalthea which was used as a drinking-horn for the baby Zeus. The second passage is in Pausanias’ discussion of the battle of Thermopylae, where he makes a specific parallel between Achilles and Miltiades, saying that few wars ‘owed their brightest glory to the valour of a single arm, as the Trojan war was ennobled by Achilles, and the battle of Marathon by Miltiades’ (3.4.7). I shall return to Miltiades below in the discussion of the Painted Stoa.

It is perhaps surprising that Pausanias only cites one temple as having been built in Athens from the spoils of Marathon, although such spoils are repeatedly cited as providing the means to commemorate and celebrate the victory. He tells us the temple’s location (the Agora) and its attribution (Eucleia, or Good Fame), saying nothing of its style, size, architecture, or any sculptural decoration (1.14.5). But this brief mention prompts the sentiment that ‘I surmise that [Marathon] is the victory of which the Athenians were proudest’. Clearly, the temple’s claim to fame in his view was that it was built from the spoils of Marathon and thereby enhanced by association with the most Athenian of victories.

A second temple Pausanias says was built from the spoils of Marathon poses more difficulties, however: that of Athena Areia (‘Warlike Athena’) at Plataea (9.4.l-2). Plutarch (Aristides 20.3), on the other hand, says the temple was built or rebuilt (there is a textual problem)21 from the spoils of Plataea, and not Marathon. This is more logical for a temple at Plataea, but we cannot know for certain. What is intriguing, though, is that two near-contemporary sources should attribute the temple to different battles, suggesting that what counted for most was the broad association with Persian war glory. Although nothing in Plutarch’s narrative proves he visited Plataea, he must surely have done so, as he was a Boeotian, and he tells us that the graves of Greek warriors killed at Plataea were washed annually in his day (Aristides 21.5), which he most probably knew from first-hand experience. Pausanias also visited Plataea, and it is a fair assumption that the locals told him of the association with Marathon. The matter is not clarified by the statue Pausanias saw inside the temple, of Arimnestus, who commanded the Plataeans at both battles. It might seem strange that Pausanias’ informants, the local inhabitants, would not claim association with the battle of Plataea, but the only people who fought with the Athenians at Marathon were the Plataeans, and Marathon may have had even greater resonance for the Plataeans in terms of their perception by other Greeks, if Pausanias is right that ‘before the battle which the Athenians fought at Marathon, the Plataeans had no title to fame’ (9.1.3). Either way, therefore, the story reflects glory upon the Plataeans.

As to the temple itself, Pausanias describes the cult-statue: ‘The image is of wood gilded, but the face, hands, and feet are of Pentelic marble. In size it falls little short of the bronze image on the Acropolis, which the Athenians also dedicated from the spoils of the battle of Marathon. It was Pheidias who made the image of Athena for the Plataeans as well as for the Athenians’. The parallel with the Athena Promachus, the most striking outdoor statue on the Acropolis of Athens, reinforces the links already mentioned between the Athenians and the Plataeans. Of the interior of the temple, Plutarch (who says nothing of the cult-statue) simply tells us that it had ‘frescoes, which continue in perfect condition to the present day (Aristides 20.3). Pausanias, characteristically, describes these paintings in more detail: ‘one of them, by Polygnotus, represents Odysseus after he has killed the wooers; the other, by Onasias, depicts the former expedition of the Argives, under Adrastus, against Thebes. These paintings are on the walls of the fore-temple’ (9.4.2).

Turning to the Painted Stoa in the Agora of Athens, the paintings of Marathon, Amazons, Troy, and Oinoe are described by Pausanias (1.15.1-3)22 in a passage which is one of the most discussed of all sources for ancient art.23 The stoa was not, as far as we know, funded by the spoils of Marathon, perhaps because it seems to have been Cimon’s project, so it had a personal agenda rather than a state agenda as temples and treasuries had, specifically, the glorification of Miltiades. On the paintings, executed around the mid-fifth century and therefore about contemporary with the Delphi Marathon group, Miltiades is depicted, as at Delphi, alongside the goddess Athena and the hero Theseus, founder of modern Athens.24 In Athens, though, he is also shown alongside Callimachus, a fellow-commander at Marathon, Heracles, whom the people of Marathon were the first to regard as a god, according to Pausanias (1.15.3, 32.4), and the hero Echetlus. The latter is mentioned again by Pausanias (as Echetlaeus) in his description of the battlefield of Marathon: ‘they say that in the battle there was present a man of rustic aspect and dress, who slaughtered many of the barbarians with a plough, and vanished after the fight. When the Athenians inquired of the god, the only answer he vouchsafed was to bid them honour the hero Echetlaeus’ (1.32.5). Similarly, Herodotus tells us of Epizelus, an Athenian soldier in the battle of Marathon, who ‘was fighting bravely when he suddenly lost the sight of both eyes, though nothing had touched him anywhere … he was opposed by a man of great stature in heavy armour, whose beard overshadowed his shield; but the phantom passed him by, and killed the man at his side’ (6.117). Aelian, writing later in the same century as Pausanias, tells us (Varia Historia 7.38) that Epizelus was depicted in the Painted Stoa, although Pausanias himself does not mention him.

Another hero mentioned by Pausanias in connection with the Persian wars, and specifically the defence of Delphi, is Phylacus, whose precinct is said to be by the temple of Athena Pronoea (Forethought) at Delphi (10.8.7).25 Pausanias may have seen the precinct of Phylacus for himself, or may have depended on the account of Herodotus (8.38-39), who gives the same location, but he adds the detail that Phylacus, and Autonous, another local hero who fought the Persians with him, were ‘two gigantic hoplites – taller than ever a man was – pursuing them and cutting them down’. Phylacus also appears against the Gauls in 279 (10.23.3), during an account of the battle in which Pausanias includes supernatural signs, including ghosts of four heroes.26

The element of the supernatural evident in the appearances of Echetlus and Epizelus at Marathon is manifest also in the support of the local god of Marathon: ‘Philippides said that Pan met him about Mount Parthenius, and told him that he wishes the Athenians well and would come to Marathon to fight for them’ (1.28.4). Pausanias tells us that manifestations of the supernatural at the battlefield of Marathon persisted until his day: ‘Here every night you may hear horses neighing and men fighting’ (1.32.4). Nor was this confined to Marathon: at Salamis, ‘It is said that while the Athenians were engaged in the sea-fight with the Medes a serpent appeared among the ships, and the god announced to the Athenians that this serpent was the hero Cychreus’ (1.36.1). No wonder the ‘Athenians tell in song how gods fought on their side at Marathon and Salamis’ (8.10.5).

The preceding discussion indicates the context in which Miltiades effectively achieved the status of hero and was sufficiently raised above ordinary mortals to be depicted in paint and bronze alongside gods and heroes at Athens and Delphi. One explanation for his special treatment is obvious: his son was Cimon, the leader of Athens in the generation after the Persian wars, the man who finally saw off the Persian threat in the 460s, and brought the bones of Theseus, the founder of Athens, back from Scyrus, as Pausanias tells us (1.17.6), noting that the Athenians dedicated a σηκός to Theseus to house the bones following Marathon.

Cimon probably commissioned the Painted Stoa, originally named the Peisianacteion after Peisianax, his brother-in-law. The urge to promote his father’s image seems to have been irresistible to Cimon. But Pausanias indicates another reason for this elevation of Miltiades: in his description of the area of Marathon (1.32.3-7), he says ‘the people of Marathon worship the men who fell in the battle, naming them heroes’. As a survivor, Miltiades would not come into this category, but as a victorious general he would have been a prime candidate for elevation to hero-by-association, and the clearest manifestations of that are his portraits at Delphi and Athens.

The Painted Stoa is strikingly different from other monuments we know of – and perhaps unique – since it actually depicts the battle of Marathon. It shows clearly, therefore, that the Athenians could show historical events in art if they wanted to. Why, then, did they not on the Parthenon? Is it that a different convention applied to sacred buildings, such as the Parthenon, and secular, such as the Painted Stoa? Perhaps, but, if so, that convention had been done away with by the time of the temple of Athena Nike, which shows on its sculpted frieze Greeks fighting Persians, whether generically or, as often argued, in a specific battle. But that dates from only about ten years after the end of work on the Parthenon, and it is unlikely that conventions changed so quickly. Again, what of painted pottery which, like sculpture, does not show historical events, bar a very few exceptions? We could argue that it is essentially private art, and so does not celebrate public, communal, successes like sculpture. But different ways of reasoning for different art-forms seems to me an unsatisfactory and very un-Greek solution.

Pausanias’ description of the Painted Stoa shows a parallel between the Amazons and the Persians, but not an equivalence: if Amazons stood for the Persians, there would be no need to depict the Persians as well. Pausanias’ references to continuity from what we would see as mythical wars to historical ones are in historical contexts, not artistic ones. If he saw allegories, he did not tell his readers. Here I return to pottery. In response to my scepticism about whether Amazonomachies and similar scenes on pots do reflect the Persian wars, it may well be pointed out that many scholars have cited a rise in such depictions in the second quarter of the fifth century. However, a different picture emerges from the most recent, and continuing, study of iconographic trends in vase-painting, namely that of the Archivio Ceramografico of Catania University. In presenting the work of the Archive, Filippo and Innocenza Giudice discuss what they call the ‘iconographic fortune’ of many scenes, including the great fight scenes such as the Amazonomachy, gigantomachy, and centauromachy.27

I have already mentioned the consistent popularity of the gigantomachy according to my own study of the Attic red-figured vases, and I add here that the level of representations from 490-80 is slightly less than in 520-500, and that, while there is a peak of 18 c. 480-70, there is already a falling-off between 470 and 460 with 16 and a near-standstill after that until 420.28 The numbers we are dealing with are not high, though, and make apparently dramatic statistical changes as likely as they are misleading. In addition, the imprecision of chronology means that dating to decades is hazardous.29 Similarly, looking at the charts of the Catania archive for the ‘great mythical fights’,30 it seems not only that there is quite a rise in the period before 500 (as in my study of the gigantomachy), and certainly before 490, but also a very sharp falling-off in all four cases from the first quarter of the fifth century to the second quarter. If that is so, it seems painters became bored with all four subjects within a very few years of the invasion of Athens. Finally, this pattern – peak 500-475, sharp fall 475-50 – is followed by these categories used by the Catania archive:‘deities’, Dionysian scenes, Heracles (intriguingly), heroes and various myths, the Trojan cycle, Amazons, giants, ‘exotic subjects’, ‘military life’ (although, perhaps tellingly, ‘funerary scenes’ show a distinct increase), chariots, hunting and fishing, komos, ‘erotic scenes’, and the symposium. In other words, there is a very widespread falling-off in the second quarter of the fifth century. This may suggest that painted pottery production was badly affected by the Persian wars – after all, one would expect the city’s luxury industries to fail in the immediate aftermath of the destruction. Or it may suggest that, if the Persian invasion had an effect on iconography, as opposed to production as a whole, it was a pretty widespread and indiscriminate effect.

I conclude with the Vivenzio hydria, a well-known Athenian red-figured vase by the Kleophrades Painter,31 which shows an Iliupersis often seen as an allegory for the conflict of the Greeks with the Persians and specifically the destruction of Athens.32 However, this requires a precise date very late in the painter’s career, and it seems to me that, if it refers to anything other than simply Troy, it more likely recalls the sack of Miletus in 494, as Pollitt suggested.33 Resistance (the most striking feature of the vase) was greater there than in evacuated Athens, and Herodotus (6.22) tells us that the play, ‘The Fall of Miletus’, which so moved Athenian audiences was written by a Milesian, Phrynichus. It is a reminder that the Persian Wars began with the Ionian Revolt, not with the invasion of Attica. And, in turn, that Marathon was one of many stages on the road to Greek victory.

Contribution (79-89) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.