Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Early Rally Songs

“Washington’s March”

America’s earliest presidential elections were simple contests in which the candidate who garnered the most votes won. With impassioned partisan races yet to emerge, political songs were expressions of patriotism. “The Favorite New Federal Song” came to be associated with George Washington (1732–1799) after it was played for him in 1789 during a visit to Trenton, New Jersey, the site of one of his military victories. For many years, the tune, now known as “Hail, Columbia,” did duty as a national anthem.

Celebrating John Adams

One of the most popular patriotic songs of the late-eighteenth century was “Adams and Liberty,” with words written by Robert Treat Paine (1731–1814), one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. The song celebrates all who worked for liberty, including second U.S. president John Adams (1735–1826), in office from 1797 to 1801, who is pictured in a cameo engraving on the music. The words were sung to the tune of “To Anacreon in Heav’n.” This melody is today best known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Lincoln’s Call and Andrew Johnson’s Satire

Although he is perceived today as one of America’s presidential icons, when Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) ran for office in 1860 he was not as well-known as his Democratic opponent, famed orator Stephen Douglas (1813–1861). While Douglas embarked on a speaking tour to win votes, campaign songs like “Freedom’s Call” helped to spread the word about Lincoln, promising that all who voted for him “in triumph ride at last!” Vice President Andrew Johnson (1808–1875) was thrust into the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination but when he attempted to run as a Democrat in 1868, Johnson faced biting musical satires ridiculing him for switching parties and attacking his background and character.

Songsters

A Variety of Songsters

As these examples from the Library of Congress Music Division show, songsters remained popular into the early twentieth century, when they were published as larger booklets with vocal arrangements and piano accompaniments. Some songsters promoted specific tickets, such the 1884 “Blaine-Logan Songster.” Others focused on political parties’ platforms. The 1878 “Greenback” Party songster included tunes supporting the use of paper money; the Progressive or “Bull Moose” Party songster endorsed Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) after his split from the Republicans in 1912. Songsters also reflected aspects of contemporary culture. The Democrats’ tunes for 1888 were touted as “red hot”—in the most up-to-date style.

Democrat and Whig Songsters

By the 1840s, partisan politics was well developed, and the two major parties of the day, the Democrats and Whigs, exploited the power of song as a campaign tool. Both parties published “songsters,” pocket-sized books perfect for campaigners to attract voters with an impromptu street corner rally. The earliest songsters included only lyrics printed along with the titles of well-known tunes to which they were to be sung. Two songsters from the 1844 contest between James K. Polk (1795–1849) and Henry Clay (1777–1852) offered their followers relevant new words for old standards like “Yankee Doodle” and “Old Dan Tucker.”

Forgotten Candidates

Campaign Songs for Grant’s Opponents

In the nineteenth-century, most voters got to know candidates through photographs and engravings; therefore, images on sheet music were chosen for their popular appeal. Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) entered the 1868 race as a Civil War hero; his Democratic opponent Horatio Seymour (1810–1886) not only had no war record but had openly criticized Lincoln’s war policies. Therefore on this cover, Seymour’s running mate, Francis Preston Blair, Jr., (1821–1875), a Union general, was depicted in uniform, as Grant usually was shown.

Despite charges of corruption in his administration, Grant was re-nominated in 1872. His opponent was Horace Greeley (1811–1872), founder and editor of the New York Tribune. The song, “Horace and No Relations,” pointedly referred to charges against Grant for naming family members to government positions. Yet even though Greeley had the endorsement of the Liberal Republicans and the Democrats, he and his running mate Benjamin Brown proved no match for the Republican incumbent.

Campaign Marches from 1876 and 1880

In 1876, Samuel Tilden (1814–1886) lost to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes (1822–1893). During the campaign, supporters of Tilden and running mate Thomas Hendricks (1819–1885) promoted them with this “Grand March.” In addition to being a memento of their candidacy, this sheet music was made available in arrangements for military band, orchestra, and chorus, and demonstrates the public use of campaign music. If the music was purchased with a plain title page rather than this engraved one, its price was lower.

Although Winfield Scott Hancock’s name had been proposed for candidacy several times, he did not receive enough support to run as the Democratic nominee until 1880. Campaigning against James A. Garfield, Hancock (1824–1886) was protected from virulent Republican attack because of his heroism during the Civil War, particularly during the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Identified as “General” and depicted in the same pose in which he had appeared when in uniform. Hancock is shown so that no voter could fail to recognize him.

Issues and Slogans

Political Songs of 1904

Three campaign songs offer interesting views of how the candidates in the 1904 presidential contest were presented. Celebrating his role in the Spanish-American War, Theodore Roosevelt is pictured racing with sword drawn as “The Hero of San Juan Hill.” Although the cover art is unremarkable, the lyrics to the song for Democrat Alton B. Parker (1852–1926) criticize “jingoism,” the belligerent chauvinism depicted in war images such as the one on the Roosevelt sheet music cover. Ignoring specific references to the other parties, the cover of the sheet music promoting former Democrat Eugene V. Debs (1855–1926) and other Marxist-inspired Socialists, simply promises the dawn of a new political age.

“Get on the Raft with Taft”

When Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) refused to seek a third term in 1908, he suggested that William Howard Taft (1857–1930) be nominated. With the imprimatur of such a popular politician, Taft had the advantage over William Jennings Bryan, who was running for the Democrats for the third and last time. The lyrics of “Get on the Raft with Taft” confirmed for voters that Taft was indeed Teddy’s chosen successor. Its title demonstrates how a clever political slogan could be popularized in song.

Cleveland and the Veto

Democrat Grover Cleveland (1837–1908) became known for exercising the presidential power of the veto during his first term (1885–1889). Although he saw these decisions as positive economic measures, his rejection of military pensions and assistance for farmers was unpopular. This Republican campaign song cover depicts Cleveland carrying his political “baggage” out of the White House. Straining under the weight of his administration, he has already removed a hefty bundle of vetoes, seen just in front of his feet.

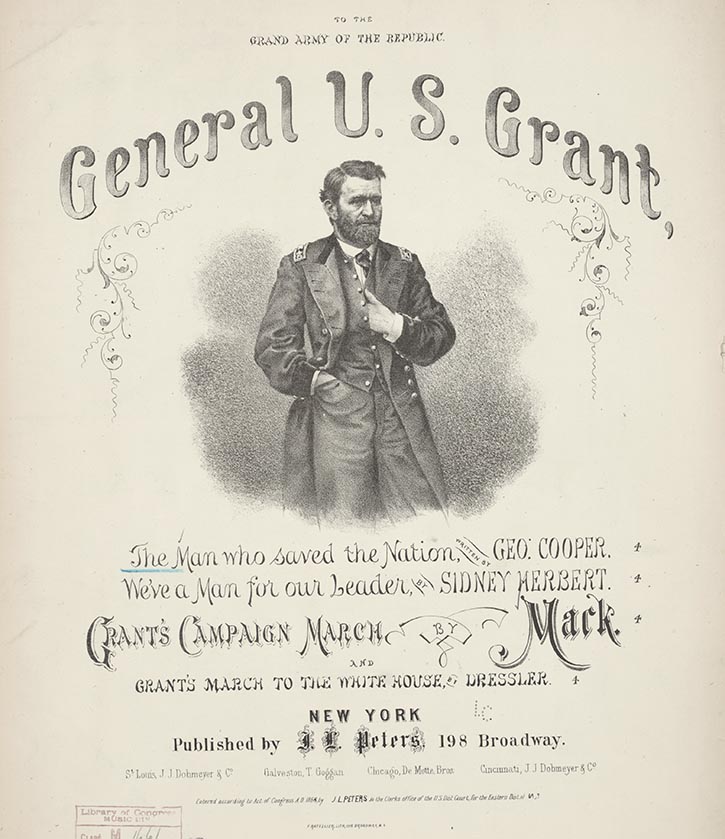

Grant, “The Man Who Saved the Nation”

Any candidate pitted against Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) in 1868 struggled against Grant’s reputation as “the man who saved the nation,” as the song title states. Since a majority of voters would have been veterans of the Civil War, the engraving of Grant in uniform would be particularly compelling. The music publisher used the same cover for four songs (the titles appear below his portrait), thereby saving money and advertising other campaign compositions.

William Jennings Bryan’s Famous Line

William Jennings Bryan (186–1925) made three unsuccessful runs as Democratic presidential nominee. In 1896, the year of his first nomination, he gave his famous “Cross of Gold” speech, advocating both silver and gold monetary standards. This sheet music cover, in rich blue and gold, memorializes the quotation for which Bryan would forever be associated: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

The Bandanna versus the Flag

Although the elephant and the donkey are unmistakable images in American politics, past elections featured other symbols. When campaigning, Grover Cleveland’s 1888 running mate, the aging and ailing Allen Thurman (1813–1895), would mop his brow with a red bandana. Democrats took this symbol to heart in song. Republicans turned this symbol to their advantage. Retaliating with tunes that depicted Thurman’s bandana as a sweat rag, they insisted that the only proper American symbol to wave was the flag.

Rutherford B. Hayes Campaign Song

Rutherford B. Hayes (1822–1893) and William Wheeler (1819–1887) were placed in the unenviable position of redeeming the Republican Party from the accusations of corruption in the two-term administration of Ulysses S. Grant. This eye-catching engraving, rich in imagery, uses the candidates’ names in word play: Uncle Sam rides to Washington on a wagon full of Hay(es), which is pulled by sturdy Wheel(er)s. Voters are assured that “honest money” will be spent in their White House.

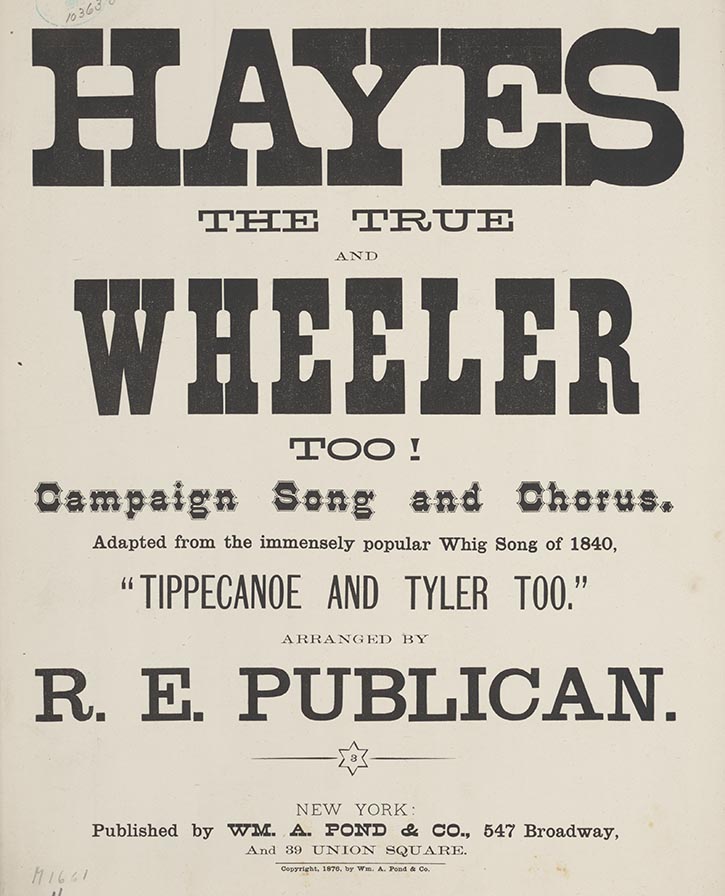

“Hayes the True and Wheeler, Too!”

Another 1876 Hayes-Wheeler campaign song used a different tactic to win the Civil War veterans’ vote. Because Grant had proven a less than model president, Republicans harkened back to another great fighter: William Henry Harrison. This song, by R.E. Publican, employed the immensely popular Whig song “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too!” Older voters might have remembered it; for those who did not, the original lyrics were included to further link the candidates with their political models.

Al Jolson Supports Harding

Although most of his show business colleagues were Democrats, Al Jolson (1886–1950) was an avid Republican. Using his star power to stump for Warren G. Harding in 1920, he wrote and performed “Harding You’re the Man for Us.” Although the sheet music prominently listed him as its composer to entice voters with his endorsement, its cover focused on photographs of Harding and his running mate, Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933), for whom Jolson would campaign in 1924.

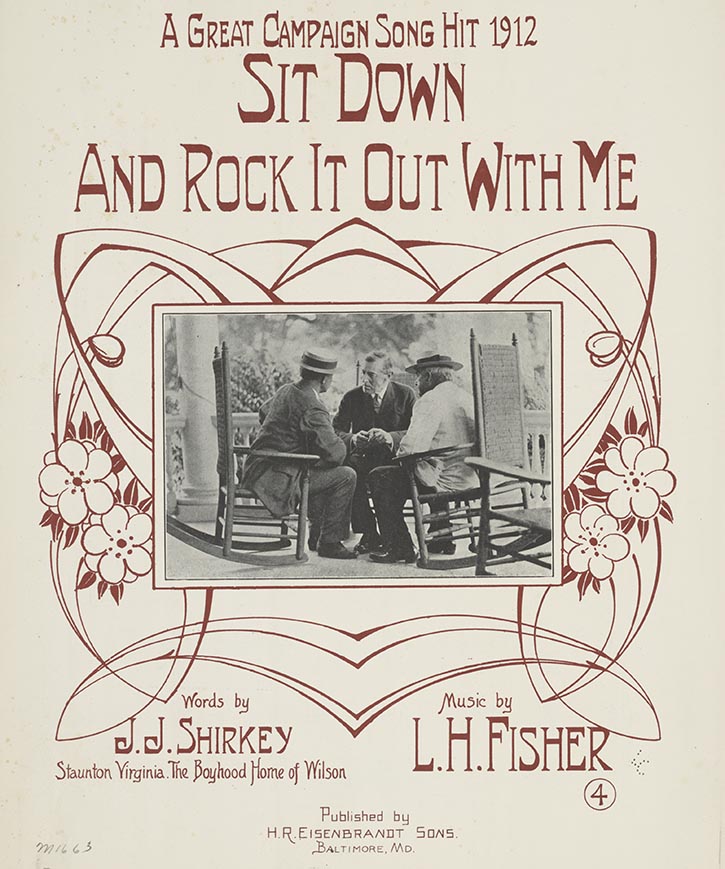

1912 Campaign Songs

Three candidates ran in the election of 1912: Republican William Howard Taft, renegade Republican Theodore Roosevelt for the Progressive Party, and Democrat Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924). The Republican split improved Wilson’s chances. Nevertheless, his campaign planners took care in presenting his image, even on sheet music. One song cover featured Wilson listening to his constituents as they sat in rockers on the porch of his “little white house in New Jersey.” This gentler side was countered by the stern image of the “trust buster” who demanded that business power be taken away from price-fixing interest groups and returned to the people.

A Changing Political Climate

Two Democratic election song covers illustrate how the national climate changed during Woodrow Wilson’s second term. One comic song was used to campaign for Wilson’s re-election in 1916. The Democratic donkey’s feed pail lists his platform: an eight-hour work day, a child labor law, federal-reserve legislation, farm credits, and peace. The patched-up elephant in the next stall offers only platitudes, promises, and criticism. The campaign in war-weary 1920 was more somber. Democratic nominee James M. Cox (1879–1957) continued Wilson’s push to join the League of Nations. The cover art addresses the country’s mourning of thousands of World War I casualties buried in Europe. The lyrics support the League’s diplomacy instead of Warren G. Harding’s idea of “Peace by Resolution,” a separate Congressional declaration of peace.

Songs for the 1924 Election

One of the most famous political scandals of the twentieth century involved the Teapot Dome oil reserves. This matter and other charges of corruption in the Harding administration threatened Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933), who took office when Harding died in 1923 and ran for re-election a year later. This cartoon cover art shows the Democrats kicking the corrupt Republicans’ teapot. In spite of the shadow the previous administration cast over his campaign, Coolidge easily defeated opponent John Davis (1873–1955).

Despite an administration burdened by scandals such as Teapot Dome, Vice President Calvin Coolidge nevertheless managed to win his party’s nomination as well as the election in 1924. Once again, Al Jolson helped the Republican Party by crooning “Keep Cool with Coolidge.” Other songs such as this one evoked a dignified White House worthy of the man who bore the nickname “Silent Cal.”

Songs for Smith and Landon Campaigns

Alfred E. Smith (1873–1944), four-time governor of New York, ran for the presidency against Republican Herbert Hoover (1873–1944) in 1928. This campaign song cover capitalizes on his popular image as “Al” Smith. A workman tips his hat to the genial candidate, trusting, the cover art suggests, that he would represent the nation’s workers. However, Smith’s Roman Catholicism became a campaign issue, and Hoover, although he had a less approachable personality, won the election by a landslide.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt broadcast his first “fireside chat” in 1933. His use of the nation’s airwaves to promote New Deal programs as solutions to the Depression’s economic woes became the butt of satire three years later when, during his bid for a second term, he faced Republican Alfred “Alf” Landon (1887–1987). In this song, billed as “The Country’s Favorite Comic Song,” opponents suggest that voters, plagued by unemployment and inflated taxes, should not trust what they hear on the radio.

“Good-Bye Prohibition,” 1932

In 1919, the sale of “intoxicating liquors” was banned. An end to Prohibition became a campaign issue for Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) during his first run for office in 1932. On this cover, a smiling F.D.R. watches as the Republicans’ “1920 model” gets a kick from the Democratic donkey, which is fed by votes. The song’s lyrics grew serious as they welcomed the demise of bootlegging and mobsters who had profited illegally during the liquor ban.

“Humanity with Sanity,” for Landon and Nixon

Composer/publisher William Seiffert liked the slogan “Humanity with Sanity” so much that he used it in his musical campaigns for two sets of Republican candidates. In 1936, he wrote a song supporting the Alf Landon and Frank Knox run against Franklin Delano Roosevelt and John Nance Garner (1868–1967). Twenty-four years later, Seiffert, employing new lyrics and a new melody, re-used the title for the campaign of Richard Nixon (1913–1994) and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., (1902–1985) against John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) and Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973).

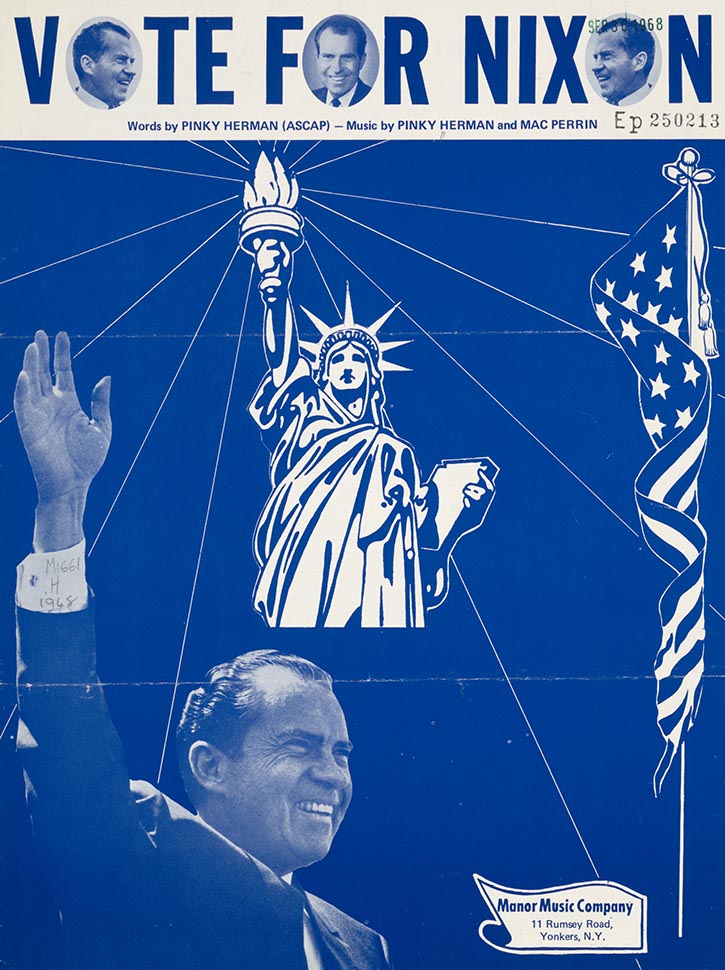

Songs for Kennedy, Johnson, Humphrey, and Nixon

“Kennedy and Johnson,” a song published in Johnson’s home state of Texas, relayed the simple promise that the nation’s hope would be renewed. The sole serious thought in the lyrics of “Hubie Humphrey—We Love You!” suggested that the candidate would “get our boys out of Viet Nam.” Also shown are the music and lyrics for the 1968 “Vote for Nixon.”

“Let’s Carry Barry to the White House,” 1964

The Music Division’s rich collection of campaign songs includes copyright deposits sent to the U.S. Copyright Office for registration. This song, written for the 1964 campaign of Republican Barry Goldwater (1909–1998) was never published as sheet music but was copyrighted before it was recorded as the “B” side of a novelty 45-rpm record. Here its lyrics are preserved as they were submitted for copyright protection.

For or Against F.D.R.

In 1940, Republican Wendell Willkie (1892—1944) faced two-time winner Franklin Roosevelt (1882–1945). This parody of “Casey at the Bat” is full of political satire. A gleeful F.D.R. recalls Willkie’s debate (“de-bait”) with Solicitor General Robert Jackson. Meanwhile, Willkie, a fierce critic of F.D.R’s Tennessee Valley Authority, misses another pitch, despite coaching from former president Herbert Hoover (1874–1964). There would be no joy on Wall Street, the lyrics state, when the former industrialist strikes out, a call made by the umpire (the American people).

During his presidency (1932–1945), F.D.R. guided the nation through much of the Great Depression and World War II. This campaign song, published in 1944, depicts Roosevelt heading back to Washington on the Democratic donkey, an ironic image given his paralysis. Aware of Roosevelt’s poor health, the Democrats nominated Harry S Truman (1884–1972) for vice president in case Roosevelt did not survive the term. In fact, just five months later, Truman took the oath of office.

Campaign Songs from 1952

Adlai Stevenson, Jr., (1900–1965) ran as a Democrat in 1952. This campaign song cover united all elements of middle-class America: the farmer, the businessman, and the blue-collar worker, who reveled in the prosperity won during the administration of Harry S Truman. As the lyrics proclaimed, the farmer had money, the workman drove a coupe, and the businessman could “sleep at night.” A vote for the Republicans would threaten a solid economy. “Don’t let ‘em take it away!” the song urged.

As a child in Texas, Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969) was called “Ike.” This nickname followed him through his military career and inspired one of the most memorable campaign slogans of the twentieth century: “I Like Ike.” Voters in 1952 sported this saying on buttons and saw it everywhere on campaign posters. Irving Berlin turned it into a campaign song. Variations appeared, of course, including this piece which made the slogan more inclusive: “We like Ike.”

Links to Family or Past Presidents

Connecting to Past Presidents

One way to secure voter confidence was to invoke the names and images of great past presidents. In his first two runs for the nation’s highest office, William Jennings Bryan was linked on sheet “Patriotic National Silver Song” refers to Bryan’s crusade for a monetary standard using both gold and silver. A 1920 campaign song cover pictured Warren G. Harding (1865–1923) with former Republican presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William McKinley. Instead of Harding’s other Republican predecessor, William Howard Taft, Abraham Lincoln is in the center under the broad embrace of Uncle Sam.

Grover Cleveland’s Bride

Frances Folsom (1864–1947) married Grover Cleveland during his first term as president 1885–1889. Scandal, no stranger to Cleveland, soon swirled around his young bride. One rumor accused her of infidelity; another suggested she was a battered wife. To counter these attacks, Democrats blatantly exploited her image in a positive light during Cleveland’s 1888 campaign for re-election. Aimed at a female audience even though women could not vote, these lyrics mention “Frankie” Cleveland Clubs, popular groups inspiring women to become interested in politics.

Family Traditions

The quest for the nation’s highest offices often ran in families. In 1840, William Henry Harrison (1773–1841) was elected president. Forty-nine years later, his grandson Benjamin (1833–1901) wrested the White House from the incumbent, Grover Cleveland, by linking himself to his grandfather. When Cleveland returned triumphant in 1892, his vice president was Adlai Stevenson, Sr., (1835–1914), who ran on a ticket with presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925) in 1900. Stevenson’s second try proved unsuccessful, as did the presidential race of his son Adlai, Jr., (1900–1965) against Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969) in 1952.

McKinley, “The Voice of the Buckeye”

The cover art of “The Voice of the Buckeye,” sheet music for William McKinley’s 1896 campaign, is rich in imagery. Cherubs point to the title that lauds his origins as a native of Ohio, the Buckeye State. Along the bottom are representations of the volunteer regiment he commanded. Most powerful is his depiction as a family man. Flanked by his wife and grandmother, McKinley (1843–1901) is shielded under the powerful wings of the American eagle.

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress, 10.09.2008, to the public domain.