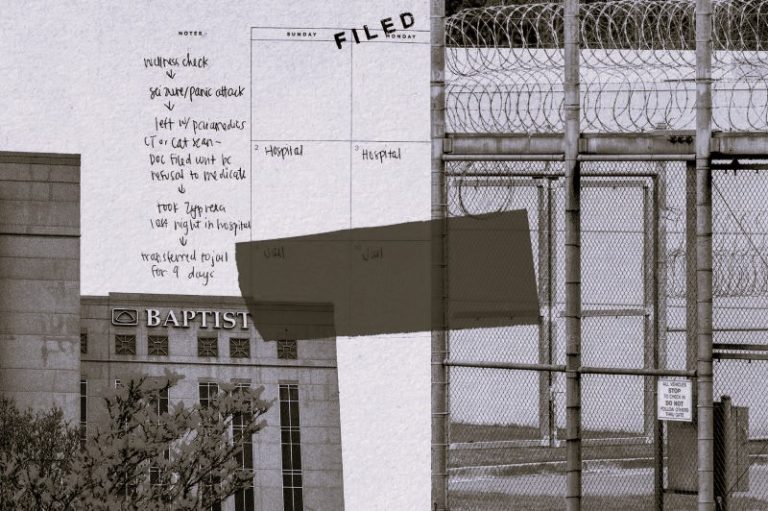

The Austin State Hospital is shown on April 29, 2016. Despite an infusion of funding from lawmakers for the state’s mental health care system, Texas struggles to provide psychiatric care for all patients who need it.

By Edgar Walters / 05.01.2016

When Stephanie Contreras picked up her son last October from a private psychiatric hospital in South Texas, “he was white as a sheet, blue in the lips,” she said.

Her son’s emergency hospitalization had been intended to stabilize his mental illness, but she found him on the verge of a diabetic coma. He had failed to receive proper medication, she said. Contreras, who lives in McAllen, believes this would not have happened if he had been able to get care at one of Texas’ 10 state hospitals for people with severe mental illness, where he had stayed before. But in at least five cases over about a decade, Contreras said, her son was turned away from state hospitals because they were full.

“He was emotionally traumatized” by the difficulties of getting into high-quality psychiatric care and facing a shifting team of medical professionals, she said. “Time after time, there would be no beds in the Valley.”

Contreras’ son, now 36, has schizoaffective disorder, which includes schizophrenia and mood disorder symptoms. Over an 11-year period of his adult life, he spent more time in psychiatric hospitals than in the outside world, Contreras said. But getting him into care often proved difficult. Contreras remembered spending long nights in the emergency room, calling private and public hospitals to see if any had space to take him in for stays that ranged from two weeks to three months.

Despite an infusion of funding from lawmakers for the state’s mental health care system, Texas struggles to provide psychiatric care for all patients who need it. Crumbling, century-old state hospitals today have around 400 people on waiting lists, and the number of beds the state pays for in private facilities has not kept up with the state’s rapid population growth. At the same time, publicly funded options for people who need mental health care but are not yet in crisis are even harder to come by, experts say.

Advocates for people with mental illness say the result is a public health emergency. The longer people must wait to get emergency mental health care, the greater a danger they pose to themselves and others, advocates say. They hope to persuade Texas lawmakers in 2017 to finance more psychiatric hospital beds, but where those beds would go — and where the money would materialize from to pay for them — remains to be seen.

Contreras, now the executive director of said the Rio Grande Valley affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said her son has enjoyed a “blessed” life despite his medical issues. In 2014, he graduated with an associate’s degree in architectural drafting.

But in her work advocating for people with mental illness, Contreras said her son’s challenges with the current system are instructive, as she regularly encounters people who struggle to get adequate and timely mental health care close to home.

In the face of criticism, Texas lawmakers tout recent improvements to the state’s mental health safety net. They point to new funding that encourages mental health professionals to practice in underserved areas, an expansion of innovative behavioral health care programs paid for by Medicaid and new telemedicine regulations intended to make it easier for patients to connect with psychiatrists remotely.

In March, the Senate’s chief budget writer and former Health and Human Services Committee chairwoman, state Sen. Jane Nelson, R-Flower Mound, said Texas had invested “significant resources” in mental health care in recent years. Her office calculated that public expenditures on mental health care had grown by $192 million from the 2013 legislative session to the 2015 session. And when mental health spending from Medicaid, the joint state-federal insurance program for the poor and disabled, is included, total spending was up $483 million, she said.

“We have serious challenges to address, but I want to make sure we have a true understanding of our commitment to mental health — by knowing not only how much we are spending but also how we are spending the funds,” Nelson said in an emailed statement.

Still, the number of state-funded beds in psychiatric hospitals has remained flat since 2013, hovering around 2,900 at any given time, according to the Department of State Health Services. That includes capacity in the state hospital system as well as state-contracted beds at private facilities.

More troubling for advocates is a decline in the number of beds relative to the state’s population. As Texas has grown, the per-capita psychiatric hospital capacity has fallen, from 11.3 to 10.5 beds per 100,000 people between 2013 and 2015.

Hospital Capacity

Texas’ population growth has outpaced modest growth in psychiatric hospital capacity in recent years. Capacity includes beds in state hospitals and in outside facilities.

State public health officials say there were 388 people on waiting lists for state hospitals as of April 1.

“Almost all of our state hospitals are currently at capacity, and we are admitting patients as soon as other patients are discharged,” said Christine Mann, a spokeswoman for the Department of State Health Services.

Meanwhile, more than half of state hospital beds go to people who have been ordered there under a “forensic” commitment through the criminal justice system. Texans who were found by a court to be not guilty of a crime by reason of insanity or who were considered incompetent to stand trial currently fill about 1,200 state hospital beds.

That leaves only about 1,100 beds available at any given time for people, like Contreras’ son, who seek treatment outside of the criminal justice system.

For patients in the Houston area, non-forensic or “civil” commitments to a state hospital are particularly hard to come by, which has prompted Texas to contract with public and private facilities not operated by the state.

The Harris County Psychiatric Center is “largely filling” the gap for civil commitments, said Stephen Glazier, the hospital’s chief operating officer. In 1988, Glazier said, there were 1,525 people in the Houston area admitted to state hospitals through civil commitments. By 2013, he said, that number had fallen to two.

Glazier’s 276-bed facility — Houston’s primary safety net hospital for psychiatry — is “functionally full,” he said, which means that if there is an empty bed, it’s only because there’s an assigned patient who hasn’t arrived yet. About 14 percent of patients are “super-utilizers” who are likely to be readmitted because they have few options for supportive care after they’ve been discharged.

“We discharge many people to a [homeless] shelter,” Glazier said. “We see a lot of chronic recidivists, and we see a lot of rapid readmits within 30 days.”

Who gets treatment at state hospitals

Patients can either be ordered to enter state mental hospitals through criminal courts (forensic commitments) or seek care on their own or through a civil court order (civil commitments). At any given time, there are about 1,200 forensic patients and 1,100 civil patients in state mental hospitals. Here are the primary ways patients can enter state mental hospitals.

CIVIL COMMITMENTS

Voluntary – 25% of Civil Commitments

Patients voluntarily seek care at a state mental hospital and are admitted after being asessed by hospital staff.

Involuntary – 75% of Civil Commitments

FORENSIC COMMITMENTS

Patients are sent to a facility after a judge determines they are at imminent risk of serious harm to themselves or others.

Competency Restoration – 82% of Forensic Commitments

Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity – 18% of Forensic Commitments

At a criminal trial, the defendant is ruled not guilty by reason of insanity and is sent to a state mental hospital.

Most of Texas’ state hospitals were built in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when mental health care was poorly understood and many people with mental illness were expected to spend their lives in insane asylums, said David Lakey, the associate vice chancellor for population health at the University of Texas System and a former commissioner of the state agency that oversees state hospitals. Now, he said, the buildings are decaying.

“State mental health hospitals are in really bad condition,” he said. “Every session, I would go and ask for like $100 million to repair basic things, like roofs and HVAC systems. In most years I’d get zero, and in some years I’d get $30 million.”

A recent Department of State Health Services study determined that five state hospital facilities — Rusk, Austin, San Antonio, Terrell and North Texas at Wichita Falls — were beyond repair and should be replaced. Buildings at other facilities should be repaired and renovated, the study recommended.

The Austin State Hospital is shown on April 29, 2016. Officials said that as of April 2016, state hospitals have nearly 400 people on waiting lists, and the number of beds the state pays for in private facilities has not kept up with the state’s rapid population growth.

Some advocates for people with mental illness say a solution would be for the state to build new facilities, but such a proposal would be costly. Replacing the large hospitals is estimated to cost about $180 million each, according to Lakey. And the total price tag for replacing the five hospitals, repairing the remaining hospitals and adding capacity is closer to $2 billion.

As an alternative, Lakey pointed to the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler, which converted an empty ward in a university building into a mental health hospital. Lakey said similar public-private partnerships could be a cheaper and effective solution that the fiscally conservative Legislature might find palatable.

Advocates like Contreras say that until the state finds more capacity, thousands of Texans in mental health crises will suffer.

She recalled the story of a woman in her 60s in the Cameron County jail who sought treatment at a state hospital because she had a psychotic disorder that caused her to lose touch with reality. Working for the National Alliance on Mental Illness on the woman’s behalf, Contreras said she made several calls and secured a court-ordered transfer for the woman from the jail to the Rio Grande State Center, a state hospital.

But as an intermediate step, the woman underwent a routine medical exam at a local private hospital. When a nurse drew blood, Contreras said the woman passed out and hit her forehead on the floor, leaving a bloody gash. The state hospital, Contreras said, declined to accept the patient because of the injury.

“Even though she was under a judge’s order to be in jail and then transferred directly to Rio Grande State Center, she was put in a taxi — you’re not going to believe this — and the taxi driver drove into a canal,” Contreras said.

“So here we have this woman, over the age of 60, she’s psychotic, she’d been in jail, she had a gash in her forehead, floating in the dirty canal,” she continued. “I have so many stories.”

Mann, the Department of State Health Services spokeswoman, declined to discuss a specific patient’s case. But in an email, she said it would be “standard practice” for a state hospital to refer a person needing immediate medical attention to an outside health care provider for treatment.

Forensic Commitment Waiting List

The number of people sent to state hospitals through criminal courts has grown, but those hospitals have struggled to accommodate them. The waiting list for forensic patients — including people on the maximum-security list — has grown since 2013.

Advocates who seek to improve access to mental health care in Texas say the state will need to do more than just expand the number of hospital beds for patients in crisis. Despite applauding state lawmakers’ recent investments in mental health care, they still have a long list of recommendations for improvement. That includes raising Medicaid payments to psychiatrists, psychologists and other mental health care providers and boosting funding for community-based services and affordable housing.

The solution isn’t just to build more hospitals, said Andy Keller, president and chief executive of the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute. He said the state should provide options for people before they reach a mental health crisis.

Keller said making more services available to people after they are discharged can help them avoid being readmitted, ultimately reducing the overall demand for psychiatric beds.

“Families, a lot of times, are under this sort of illusion that people go to the hospital forever,” he said. “That’s not what happens.”

“We have to look at the flow out [of hospitals], as well as the flow in,” he said.

Keller said state law restricted the ability of social workers and health care providers to do effective outreach, under a program known as Assertive Community Treatment, to work with people at risk of being hospitalized. That program requires even the neediest Texans, such as the homeless, to undergo hourslong assessments before they are eligible for subsidized services, Keller said. People who do not have a stable place to live or are unaware they have a mental illness are unlikely to get assessed for treatment.

Alison, a Houston mother who spoke on the condition that her last name be kept private, offered the story of her adult son as an example. She said he has paranoid schizophrenia and a history of assaulting family members and strangers. Arrest records show her son, who is in his mid 20s, has a criminal history in Texas and Florida. On several occasions, Alison said, a judge has ordered a short-term commitment for her son at a private psychiatric hospital.

But because he has anosognosia, or a lack of awareness of his illness, he is skeptical of his need for treatment and mistrusts the people who try to help him, Alison said. He is currently homeless, living out of his car, she said.

In order to get him into a psychiatric hospital, she must wait for law enforcement to get involved, which only occurs whenever her son is considered a public safety risk, such as the time he assaulted a roofer on top of a neighbor’s home, Alison said. Until then, she can’t get her son into a psychiatric bed if he doesn’t want to go.

“When you have gotten to the point where you are presenting as an imminent risk of serious harm, that is a painful thing to wait for,” said Alison, who attends National Alliance on Mental Illness support group meetings. “What that has meant for us is, now he is assaulting someone, now we get to call the police. But before that I can see it coming.”