To remember the ancients is to remember that law does not simply protect; it can dominate, sanctify inequality, and dramatize fear.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Law Ceased to Protect and Began to Rule

Law is too often imagined as a neutral shield. In the textbooks of antiquity, Hammurabi’s code stands as progress, Solon’s reforms as emancipation, and Roman statutes as the foundation of Western jurisprudence. These are comforting narratives, but they disguise the darker currents that run through the history of legality. Law can indeed restrain power, but it can also sharpen it.

From Babylon to Rome, rulers discovered that the courtroom and the code could serve as weapons. A statute etched in stone or a verdict handed down by trembling jurors could break rivals more effectively than a sword. The law, dressed in the rhetoric of order, could silence dissent, codify inequality, and sanctify authority. Antiquity, when viewed without nostalgia, reveals law not simply as justice but as an instrument of domination.

Codifying Inequality: Hammurabi and the Illusion of Justice

When Hammurabi issued his code around 1750 BCE, he framed himself as a shepherd king protecting the weak. The famous stele depicts Shamash, god of justice, handing the scepter of law to the monarch, presenting legality as a divine trust. At first glance, the image is one of cosmic harmony: the gods bestow justice, and the king enforces it for the benefit of his people.

The reality was harsher. The code entrenched stratification rather than leveling it. A noble who injured a commoner might pay a fine, while a commoner who injured a noble could face mutilation or death.1 Slaves, occupying the lowest rung, were treated as property with legal penalties reflecting their diminished worth. This was not equality before the law but hierarchy formalized and legitimized.

It is worth pausing here. Law in oral societies often flexed with circumstance. Codification, however, fixes inequality in stone, making it seem immutable. Hammurabi’s achievement was not only political but ideological. By embedding injustice into a sacred text, he transformed domination into divine order. The fiction of justice masked the consolidation of authority, and in that fiction lay the enduring weaponization of legality.

Harsh Measures in Archaic Athens: Draco and Solon

Athens in the seventh century BCE faced social unrest. Draco’s laws, remembered for prescribing death even for minor theft, became synonymous with mercilessness. Whether or not every penalty was truly capital, the cultural memory tells us what mattered: Athenians themselves believed their earliest codification was more terror than fairness.2 Law here was not a system of mediation but of intimidation.

Solon’s arrival a century later shifted the tone. His reforms abolished debt slavery, a genuine concession to the poor, yet he preserved property classes as the foundation of political power. Solon, often praised as the father of Athenian democracy, in fact secured aristocratic control under a new legal guise. His laws defused the threat of uprising but preserved the dominance of elites.

There is a subtle brilliance in Solon’s maneuver. Where Draco wielded terror, Solon wielded compromise. But both served the same end: stability for the ruling order. The Athenian story reminds us that law’s weaponization need not be brutal; it can be subtle, persuasive, and dressed as reform.

Religion and Authority: Pharaohs and the Legal Theology of Ma’at

In Egypt, legality was not codified in lengthy statutes nor debated in courts but flowed from the divine person of the pharaoh. His decrees embodied ma’at, the principle of truth and cosmic balance. Opposition was unthinkable. To defy a royal judgment was not simply a political act but a rupture in the fabric of creation.3

This theological structure made Egyptian law uniquely unassailable. Pharaohs did not need the harshness of Draco or the subtlety of Solon. The sacred aura of ma’at rendered legality invulnerable to critique. In such a system, the weaponization of law was complete: it required no trial, no jury, no codex. The decree was justice itself.

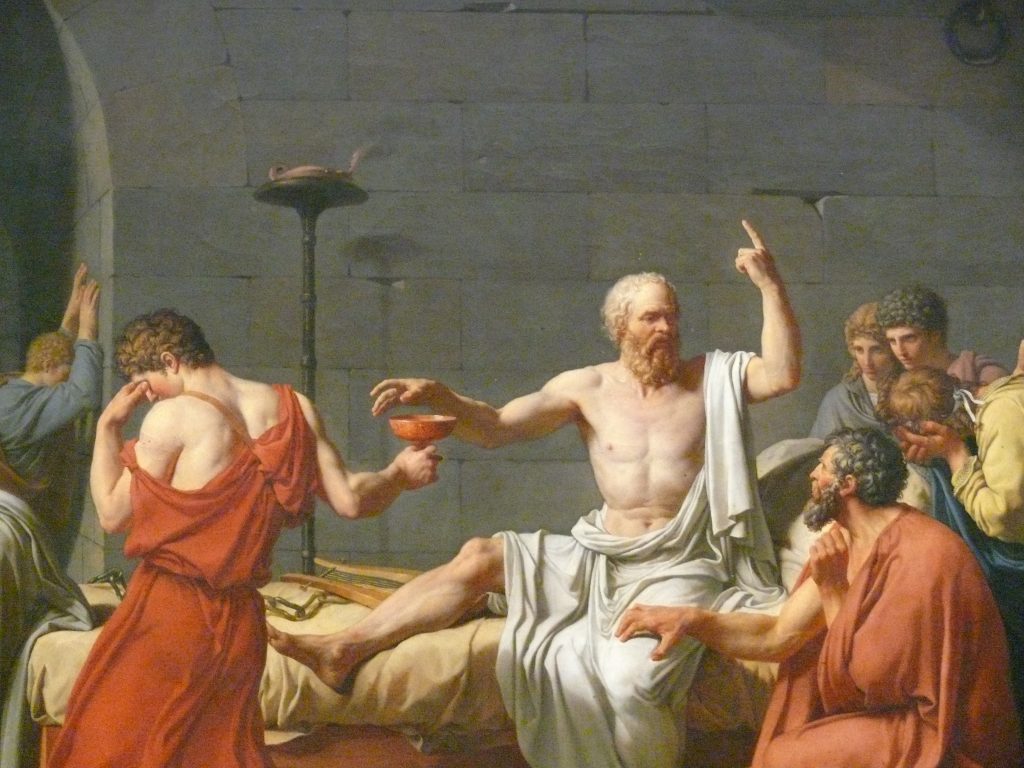

The Courts as Stage: The Trial of Socrates

No case better illustrates law as a stage for civic anxiety than the trial of Socrates in 399 BCE. The charges of impiety and corruption of youth were so vague they could mean anything. What mattered was not their precision but their utility. Athens, scarred by the Peloponnesian War and the tyranny of the Thirty, sought to purge its unease. Socrates, with his relentless questioning of authority, became the chosen scapegoat.

The trial unfolded less as legal inquiry than as performance. Socrates himself refused to flatter the jury, instead using the occasion to continue his philosophical mission. He reminded Athenians that his role was to sting them into reflection, like a gadfly on a sluggish horse. In doing so, he sealed his fate. The jurors, feeling mocked and threatened, condemned him to death.

What happened in that courtroom reveals law’s theatrical quality. It was not about evidence but about symbolism. Socrates’ execution was a ritual of purification, a legal sacrifice meant to restore civic harmony. Law became a stage where democracy dramatized its own anxieties, weaponizing justice to silence its critic.4

Rome’s Treason Trials: Tiberius and the Expansion of Maiestas

Imperial Rome perfected the art of weaponized law. The maiestas statute, designed to protect the dignity of the Roman people, was repurposed under Tiberius to shield the emperor’s person. The shift was subtle but devastating. A careless remark, a satirical poem, even silence in the Senate could now be construed as treason.

The genius, or cruelty, of this system lay in its elasticity. Vagueness made everyone vulnerable. Informers, the notorious delatores, grew rich by accusing others, while senators withered into sycophancy. Tacitus, whose biting prose spares no venom, observed that the Senate under Tiberius resembled not a council but a prison.5

The law no longer mediated disputes. It functioned as a tool of terror. Treason trials did not simply punish the guilty; they disciplined the entire elite. Fear ensured loyalty more effectively than armies. Tiberius, by wielding legality against his peers, hollowed out the institutions of the republic and replaced them with the silence of obedience.

Patterns of Weaponization: Vagueness, Theater, and Sacralization

From Babylon to Rome, three patterns recur with haunting regularity. Vagueness made law elastic. Impiety, treason, corruption of youth, all could be stretched to ensnare the inconvenient. Theater turned courts into stages where the community acted out its fears, whether in condemning Socrates or trembling before delatores. Sacralization, as in Egypt or Babylon, rendered decrees untouchable by embedding them in cosmic or divine order.

Yet the common thread is deeper. Law, for all its rhetoric of justice, became a mask for domination. Codification preserved hierarchy, courts purged dissent, decrees sanctified authority. The shield of law was always also a sword.

This recognition is not cynicism but realism. To study antiquity without facing this ambivalence is to misread it. Law is never merely a neutral code. It is a contested terrain where freedom and domination struggle, and where rulers discover that the trappings of justice can serve as their sharpest weapon.

Conclusion: The Enduring Ambivalence of Law

The ancients leave us a sobering legacy. Hammurabi’s stone, Draco’s terror, Solon’s compromises, Pharaoh’s decrees, Socrates’ condemnation, and Rome’s treason trials all show the double edge of legality. Each case demonstrates that law can promise protection while delivering submission.

This ambivalence endures into modernity. Every legal system carries within it the potential for weaponization. To remember the ancients is to remember that law does not simply protect; it can dominate, sanctify inequality, and dramatize fear. The courtroom and the code remain as much political theaters as they are sites of justice. Antiquity teaches us not to worship law blindly, but to watch carefully how it is used.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Martha T. Roth, Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), 76–83.

- Michael Gagarin, Early Greek Law (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 54–61.

- Jan Assmann, The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 71–77.

- Thomas C. Brickhouse and Nicholas D. Smith, Socrates on Trial (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 102–118.

- Tacitus, Annals, trans. A. J. Woodman (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004), 104–112.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Brickhouse, Thomas C., and Nicholas D. Smith. Socrates on Trial. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Gagarin, Michael. Early Greek Law. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

- Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995.

- Tacitus. Annals. Translated by A. J. Woodman. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.