Democratic collapse is rarely triggered by enthusiasm for authoritarianism. It is enabled by exhaustion, drift, and the quiet withdrawal of the middle.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Democracy under Maximum Stress

The crisis of the Weimar Republic in the late 1920s and early 1930s is often narrated as a story of extremist ascent. Yet this framing obscures a more consequential dynamic. Democratic collapse did not begin with mass conversion to radical ideologies, but with the erosion of confidence among moderates, independents, and former supporters of governing parties. The Republic entered its terminal phase not because polarization existed, but because the political middle no longer believed the system could manage it.

By this period, the Weimar Republic was operating under sustained stress. Successive crises had normalized emergency governance, coalition instability, and policy paralysis. Elections continued, parliaments convened, and constitutional forms remained intact. Yet the emotional and institutional foundations of democratic legitimacy weakened. Politics came to feel procedural without being productive, participatory without being responsive.

Extremist movements benefited from this environment, but they did not create it. Their growth coincided with declining voter turnout, protest voting, and the fragmentation of centrist coalitions. Many citizens did not move decisively toward radical alternatives. They disengaged, abstained, or drifted unpredictably. What appeared as polarization at the margins was, at its core, a hollowing of the center. Democratic outcomes increasingly hinged on absence rather than enthusiasm.

This moment offers a critical warning about democratic vulnerability. Systems rarely fail when opposition is loud and identifiable. They fail when rejection becomes diffuse, quiet, and difficult to address. In Weimar Germany, the decisive shift was not ideological alignment with extremism, but the withdrawal of trust from democratic governance itself. The Republic did not collapse because the middle embraced authoritarianism. It collapsed because the middle stopped believing the system could absorb crisis without breaking.

The Structural Vulnerabilities of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar constitution embodied an ambitious attempt to reconcile mass democracy with political stability after imperial collapse. Proportional representation expanded inclusion and reflected the pluralism of postwar society, yet it also fragmented parliamentary authority. Coalition governments became the norm, often composed of uneasy partners bound together by necessity rather than shared purpose. As crises multiplied, this structural dispersion of power made decisive governance increasingly difficult.

Presidential authority, designed as a safeguard, evolved into a liability. Article 48 allowed emergency decrees intended for exceptional circumstances, but repeated invocation normalized rule by exception. What began as a constitutional backstop gradually displaced parliamentary deliberation. Each decree solved an immediate problem while weakening the habit of democratic compromise. Over time, legality remained intact even as legitimacy thinned.

Electoral mechanics further amplified instability. Proportional representation lowered thresholds for entry, enabling small parties to gain seats and influence without broad support. This inclusiveness reflected democratic ideals, yet it complicated coalition formation and blurred accountability. Voters struggled to connect electoral outcomes to policy results, reinforcing the perception that participation yielded little tangible effect.

Economic governance compounded these vulnerabilities. Fiscal austerity, deflationary policy, and adherence to orthodoxy during downturns signaled responsibility to international creditors but alienated domestic constituencies. Policy appeared technocratic and remote, attentive to procedure rather than relief. As unemployment surged and social protections strained, democratic institutions seemed incapable of translating hardship into effective response.

These vulnerabilities did not doom the Republic on their own. They became fatal when layered upon one another during sustained crisis. Fragmented representation, emergency governance, and economic orthodoxy together produced a system that functioned formally while failing experientially. The Weimar Republic’s problem was not the absence of democratic mechanisms, but their inability to absorb prolonged stress without eroding trust.

Crisis without Resolution: Economy, Identity, and Democratic Fatigue

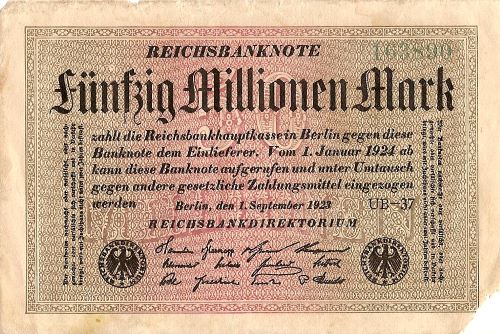

By the late 1920s, the Weimar Republic was trapped in a cycle of crisis without credible resolution. The hyperinflation of the early 1920s had been stabilized, but its psychological aftershocks endured. Savings had been wiped out, trust in financial institutions damaged, and social expectations reset downward. Even during periods of apparent recovery, many Germans experienced stability as fragile and provisional, easily reversed by forces beyond democratic control.

The onset of the Great Depression transformed this latent anxiety into open despair. Unemployment rose rapidly, social welfare systems buckled, and economic suffering spread unevenly but relentlessly. What mattered politically was not only the severity of the downturn, but the perception that democratic governance lacked the tools to respond effectively. Policies appeared constrained by orthodoxy, international obligations, and elite consensus. Relief was promised repeatedly and delivered inconsistently, deepening public skepticism.

Economic crisis also intensified questions of identity and belonging. The Republic had never fully resolved the symbolic rupture created by defeat in the First World War and the Treaty of Versailles. National humiliation, territorial loss, and the stigma of defeat lingered as unresolved narratives. Economic collapse reactivated these wounds, allowing hardship to be interpreted as evidence of national betrayal rather than structural failure. Yet for many citizens, this interpretive shift did not produce ideological certainty. It produced confusion and resentment without direction.

Democratic fatigue emerged precisely at this intersection of material deprivation and symbolic dislocation. Citizens were asked to endure sacrifice in the name of constitutional order, yet that order seemed incapable of restoring dignity or security. Participation began to feel performative rather than consequential. Voting continued, but confidence in outcomes declined. The promise that democratic procedures would eventually yield improvement lost persuasive force when conditions deteriorated faster than solutions materialized.

This fatigue did not manifest uniformly. Some turned toward radical movements offering clarity and blame. Others withdrew altogether, abstaining from participation or retreating into private survival strategies. What united these responses was not ideology but exhaustion. The Republic no longer appeared as a vehicle for collective recovery, but as a mechanism for managing decline. Politics became something to endure rather than engage.

Crisis without resolution thus proved more corrosive than crisis alone. Repeated shocks without credible recovery narrowed the emotional bandwidth available for democratic patience. Each failure reinforced the sense that institutions could neither protect nor redeem. Democratic fatigue took hold not because citizens rejected democracy in principle, but because they experienced it as permanently overwhelmed. In this condition, rejection of the system did not require belief in an alternative. It required only the conviction that waiting longer would change nothing.

Extremist Visibility and the Illusion of Majority Conversion

The surge of extremist parties in late Weimar Germany created a powerful illusion of mass ideological conversion. Electoral gains by radical movements were highly visible, dramatic, and easily interpreted as evidence that the electorate had abandoned democratic norms wholesale. Yet this reading mistakes prominence for dominance. Extremist success reflected fragmentation and volatility within the electorate more than it did a unified shift toward authoritarian belief.

The rise of the Nazi Party illustrates this distortion clearly. Its expanding vote share did not emerge from the sudden persuasion of a stable majority, but from the erosion of centrist parties, declining turnout, and protest voting. Many voters who supported extremists did so episodically rather than ideologically, using the ballot to register frustration rather than allegiance. Extremist ballots often represented rejection of governing parties rather than endorsement of radical programs.

Electoral mathematics amplified this effect. As the center fractured, smaller shifts produced outsized results. Gains at the margins appeared transformative because losses in the middle went uncoordinated. Abstention and party-switching diluted the apparent solidity of democratic coalitions while magnifying the visibility of organized extremes. What looked like polarization was, in practice, dispersal.

Public discourse further reinforced the illusion of conversion. Media attention gravitated toward spectacle, violence, and confrontation, elevating extremist presence in the political imagination. Street clashes, rallies, and inflammatory rhetoric created the sense that radical movements spoke for a larger constituency than they actually commanded. Visibility substituted for representativeness, distorting perceptions of public opinion even as many citizens remained undecided, disengaged, or ambivalent.

This misreading carried serious consequences. Treating extremist growth as inevitable mass conversion obscured the more actionable problem of center collapse. It encouraged resignation rather than intervention, fear rather than institutional repair. In Weimar Germany, the decisive failure was not that too many citizens embraced extremism, but that too many withdrew from democratic commitment altogether. Extremist visibility thrived in the vacuum left behind.

Independents, Former Centrists, and Electoral Drift

The decisive electoral shifts of late Weimar Germany occurred not among committed extremists, but among independents and former supporters of centrist parties. These voters did not experience a sudden ideological conversion. Instead, they recalibrated their engagement in response to perceived ineffectiveness. As governing coalitions failed to deliver relief or stability, loyalty weakened. Electoral behavior became provisional, contingent on immediate conditions rather than long-term alignment.

Former centrist voters often responded to crisis by drifting rather than defecting decisively. Some moved temporarily toward extremist parties as a form of protest, others abstained, and many alternated between participation and withdrawal. This volatility eroded the numerical and moral foundation of democratic governance. Parties that had once anchored the Republic lost not only votes, but the confidence required to present themselves as viable instruments of recovery.

Independents played a particularly important role in this process. Unbound by party identity, they were highly sensitive to signals of competence and trustworthiness. When policy appeared disconnected from lived experience, these voters disengaged rapidly. Their withdrawal did not register as opposition, making it harder for democratic institutions to respond. Yet their absence proved decisive. Elections were increasingly decided by who stayed home rather than who mobilized.

Electoral drift thus became a silent accelerant of democratic decline. The Republic did not lose a majority to authoritarianism before 1932. It lost coherence. As independents and former centrists withdrew consent, extremist minorities gained disproportionate influence. Democratic legitimacy eroded not through dramatic realignment, but through attrition. The middle did not choose authoritarianism. It stopped defending democracy

Governing Parties and the Collapse of Trust

The erosion of trust in Weimar Germany accelerated when governing parties appeared procedurally competent yet substantively ineffective. Coalition governments continued to form, budgets were passed, and constitutional norms were observed, but outcomes failed to improve daily life. For many citizens, governance came to feel detached from urgency. Democratic politics appeared capable of administration but incapable of resolution, a distinction that proved fatal under sustained crisis.

Policy choices reinforced this perception. Deflationary austerity, adherence to fiscal orthodoxy, and reliance on technocratic expertise signaled responsibility to elites and international creditors, yet they offered little relief to the unemployed and insecure. The gap between policy rationale and lived experience widened. Even when decisions were defensible in theory, they registered as indifference in practice. Trust eroded not because voters misunderstood policy, but because policy did not address the scale of distress.

Elite behavior compounded the problem. As parliamentary paralysis deepened, reliance on presidential authority and emergency decrees increased. These measures preserved order while sidelining representative deliberation. Governing parties defended such steps as necessary, but the effect was corrosive. Democracy appeared to function without meaningful participation, reinforcing the sense that elections no longer shaped outcomes. Legitimacy thinned as authority centralized.

The collapse of trust thus emerged from accumulation rather than rupture. No single decision discredited democratic governance. Repeated failure to translate process into relief did. Governing parties lost not because they were rejected outright, but because they no longer seemed capable of governing on behalf of the electorate. In this environment, democratic loyalty did not flip to extremism. It drained away.

Polarization without Absorption: Why the Middle Mattered Most

Polarization alone does not destroy democratic systems. What proves decisive is whether institutions can absorb the pressures polarization creates. In Weimar Germany, polarization intensified at the extremes, but the Republic’s failure lay in its inability to retain, reassure, or reintegrate the political middle. Moderates, independents, and former centrists were not asking for ideological purity. They were asking for proof that democratic governance could still function under strain.

The middle mattered because it supplied flexibility. Extremes are predictable. They mobilize reliably, oppose consistently, and rarely defect. The center, by contrast, provides the margin through which democratic systems adapt. Its support is conditional, responsive to performance rather than identity. When democratic institutions respond effectively, the middle stabilizes outcomes. When they do not, the middle disengages. In Weimar, that disengagement was neither loud nor unified, but it was decisive.

Weimar’s institutions amplified polarization instead of absorbing it. Proportional representation fragmented accountability, emergency governance bypassed deliberation, and coalition paralysis produced visible stalemate. Rather than channeling independent rejection back into democratic correction, the system converted dissatisfaction into drift. Each election clarified what voters rejected without clarifying what they endorsed. The middle did not move together. It thinned.

This thinning altered political arithmetic. Extremist parties benefited not because they persuaded the majority, but because they faced less competition from a cohesive center. Democratic legitimacy requires not universal enthusiasm, but sufficient participation to marginalize anti-system actors. Once that participation declined, minorities gained leverage. The Republic did not fail at persuasion. It failed at retention.

Weimar Germany thus demonstrates that polarization becomes fatal when institutions lack absorptive capacity. Democracies survive stress by converting rejection into reform. When that conversion fails, rejection accumulates without outlet. The middle withdraws, extremes harden, and governance loses its corrective feedback loop. The lesson is structural rather than moral: systems collapse not when they face opposition, but when they can no longer process it.

Authoritarian Opportunity and Institutional Abdication

Authoritarian opportunity in late Weimar Germany did not arise from popular demand for dictatorship, but from institutional retreat. As democratic mechanisms struggled to convert rejection into reform, key actors within the state began to prioritize order over participation. Emergency powers, initially justified as temporary safeguards, became routine instruments of governance. This normalization of exception hollowed democratic practice while preserving its legal shell, creating conditions in which authoritarian solutions could appear lawful rather than revolutionary.

Institutional abdication unfolded incrementally. Parliamentary government was not overthrown; it was bypassed. Presidential cabinets governed without reliable legislative majorities, relying on decree rather than deliberation. Each invocation of emergency authority weakened the expectation that political conflict would be resolved through representative means. The more frequently institutions circumvented democratic process to manage crisis, the more they signaled their own lack of confidence in it.

Elite accommodation played a critical role in this transition. Political, economic, and bureaucratic leaders increasingly viewed democratic instability as the primary threat, eclipsing concern about authoritarian methods. Extremist actors were tolerated, and at times enabled, not because elites embraced their ideology, but because they appeared capable of mobilizing discipline and suppressing disorder. This miscalculation rested on the belief that authoritarian forces could be controlled once installed, a belief grounded more in fear of chaos than in confidence in democracy.

The withdrawal of institutional defense proved decisive. Democratic norms depend not only on popular support, but on active enforcement by those empowered to uphold them. When courts, ministries, and political leaders ceased resisting anti-democratic maneuvers, they transformed rejection into vulnerability. Authoritarian movements did not need majority endorsement. They needed access. Institutional abdication provided it.

Weimar’s final failure was therefore not electoral, but custodial. Democracy collapsed when those responsible for preserving it chose procedural continuity over substantive defense. Authoritarian opportunity emerged not from irresistible popular pressure, but from the absence of institutional resistance. The lesson is stark: when democratic systems stop protecting themselves, rejection no longer dissipates. It consolidates.

Conclusion: When Rejection Becomes a Systemic Warning

The collapse of the Weimar Republic underscores a critical distinction between rejection and conversion. Democratic systems do not fail only when citizens embrace authoritarian alternatives. They fail when rejection accumulates without institutional response. In late Weimar Germany, the decisive shift occurred not when extremists gained visibility, but when moderates, independents, and former centrists withdrew confidence in democratic governance. That withdrawal signaled vulnerability long before it produced collapse.

This rejection did not express itself as unified opposition. It appeared as abstention, volatility, and drift. Citizens did not march together toward authoritarianism. They stepped back from a system that no longer seemed capable of managing crisis. When rejection becomes diffuse and unaddressed, it is easy to misinterpret it as apathy or resignation. In reality, it functions as an early warning. It indicates that institutions are failing to absorb stress and translate dissatisfaction into reform.

Weimar demonstrates that what follows rejection is not predetermined. Outcomes depend on whether institutions respond by restoring trust or by retreating into exception and accommodation. Democratic resilience requires active absorption of dissent, not its circumvention. When systems bypass participation in the name of stability, they convert rejection into opportunity for anti-democratic actors. The danger lies not in opposition itself, but in institutional surrender.

The warning carried by Weimar is therefore structural rather than moral. Democratic collapse is rarely triggered by enthusiasm for authoritarianism. It is enabled by exhaustion, drift, and the quiet withdrawal of the middle. When rejection is treated as noise rather than signal, systems lose their corrective capacity. History does not insist on repetition, but it does insist on attention. When rejection becomes systemic, the choice is no longer between stability and chaos. It is between democratic renewal and abdication.

Bibliography

- Bessel, Richard. Political Violence and the Rise of Nazism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

- Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship. New York: Praeger, 1969.

- Childers, Thomas. The Nazi Voter. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

- De Loera-Brust, Antonio. “Review: How the Weimer Republic Paved the Way to Its Own Ruin.” America: The Jesuit Review (April 17, 2020).

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin, 2003.

- Graf, Rüdiger. “Either-Or: The Narrative of ‘Crisis’ in Weimar Germany and in Historiography.” Central European History 43:4 (2010): 592-615.

- King, Gary, Ori Rosen, Martin Tanner, and Alexander F. Wagner. “Ordinary Economic Voting Behavior in the Extraordinary Election of Adolf Hitler.” The Journal of Economic History 68:4 (2008): 951-996.

- Kolb, Eberhard. The Weimar Republic. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Mommsen, Hans. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Peukert, Detlev. The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

- Rosanvallon, Pierre. Democratic Legitimacy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction. New York: Viking, 2006.

- Turner, Henry Ashby. German Big Business and the Rise of Hitler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Weitz, Eric D. Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.20.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.