The history of the Star Chamber demonstrates that repression does not require the abandonment of law. On the contrary, it often depends upon law’s adaptability.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Authority, Speech, and the Fear of Print

The Tudor state did not fear speech in the abstract. It feared circulation. In a political culture long accustomed to oral exchange, patronage networks, and limited manuscript transmission, the sudden expansion of print radically altered how ideas moved through society. Words could now escape courtly containment, reach anonymous readers, and persist beyond the moment of utterance. This shift transformed political speech from a localized act into a structural risk. Authority, once reinforced through proximity to the monarch, ritualized displays of loyalty, and the slow diffusion of rumor, now confronted an information environment that multiplied audiences and accelerated interpretation. Print collapsed distance, weakened traditional gatekeepers, and enabled commentary to move faster than correction or suppression. What unsettled the Tudor regime was not merely the presence of dissenting ideas, but the loss of temporal and social control over how those ideas were encountered, debated, and remembered.

This anxiety was not born of liberal contradiction. Tudor rulers did not imagine themselves suppressing “free speech” in the modern sense. Rather, they understood order as a fragile achievement, maintained through hierarchy, obedience, and the careful management of reputation. Criticism, satire, and unlicensed commentary threatened not policy alone but legitimacy itself. The problem was not disagreement but interpretation. When subjects began to interpret royal actions publicly and independently, authority appeared less absolute, less sacred, and more vulnerable. Print did not create dissent, but it magnified it in ways the existing legal framework was poorly equipped to handle.

The common law courts, with their juries, evidentiary standards, and procedural constraints, were ill-suited to this new informational reality. They required clear acts, defined harms, and conventional forms of proof. Political speech, however, often operated through implication, tone, and context. It could be destabilizing without being overtly rebellious. The Crown required legal instruments capable of addressing perceived threats before they hardened into resistance. This need produced a reliance on extraordinary jurisdictions that could operate flexibly, interpretively, and preemptively. Among these, the Star Chamber emerged as a central mechanism for disciplining speech without abandoning the appearance of legality.

What follows argues that the Tudor struggle over print and political commentary represents an early modern blueprint for the criminalization of dissent through law rather than brute force. The Star Chamber did not silence England through mass repression. It did so through selective prosecution, exemplary punishment, and the expansion of sedition to encompass interpretation itself. By targeting printers, pamphleteers, and writers whose work shaped public understanding, the Crown redirected legal attention away from violent acts and toward the management of meaning. This shift allowed repression to proceed incrementally, cloaked in judicial procedure and moral language. By examining the relationship between print culture, legal exceptionalism, and political anxiety in Tudor England, this study reveals how states have repeatedly responded to new information technologies by redefining criticism as danger. The patterns established in this period continue to inform modern debates over press freedom, legal harassment, and the boundaries of permissible speech under claims of public order.

The Tudor Political Order and the Problem of Dissent

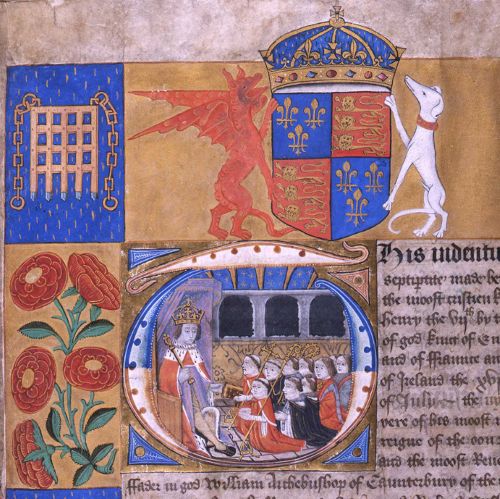

The Tudor political order emerged from crisis rather than continuity. The Wars of the Roses had exposed the fragility of aristocratic loyalty and the catastrophic consequences of contested authority. When Henry VII secured the throne in 1485, stability became the overriding priority of governance. The legitimacy of the new dynasty rested not only on dynastic claim, but on the prevention of renewed civil conflict. This imperative shaped Tudor attitudes toward obedience, criticism, and the boundaries of acceptable political behavior. Dissent was not understood as a healthy feature of governance, but as a latent threat capable of reopening wounds that had barely healed. Memories of factional violence and shifting allegiances lingered within the political class, reinforcing the belief that unity was fragile and that even small acts of opposition could escalate unpredictably.

Tudor authority was highly centralized yet structurally anxious. The monarchy relied on a limited bureaucratic apparatus, regional elites, and personal loyalty to enforce royal will across the realm. Unlike later modern states, it lacked a standing police force or a fully professionalized administrative system capable of constant oversight. This absence heightened the importance of symbolic authority, reputation, and perceived consensus. Rumor, satire, and criticism could erode confidence in the Crown in ways that were difficult to trace or contain. Political stability depended not only on coercion, but on the cultivation of deference and the suppression of visible dissent. The management of information became a surrogate for administrative reach, allowing the Crown to compensate for institutional limits through narrative control.

Within this system, dissent was rarely conceptualized as a matter of policy disagreement. It was framed instead as disloyalty, ingratitude, or moral disorder. To question the actions of the Crown was to risk being seen as questioning the legitimacy of monarchy itself. This conflation was not accidental. Tudor political thought emphasized harmony, hierarchy, and the moral duty of subjects to obey. Criticism threatened to disrupt this moral economy by suggesting that authority could be evaluated, judged, or found wanting by those beneath it.

The problem was compounded by the limits of common law. Traditional courts were designed to adjudicate disputes between parties, punish recognizable crimes, and rely on juries drawn from local communities. Political dissent, however, often took forms that were indirect, ambiguous, or anticipatory rather than violent. Pamphlets, sermons, and conversations could shape opinion without producing a clear criminal act. The common law’s demand for explicit evidence and defined offenses made it an unreliable instrument for managing what the Crown increasingly perceived as ideological danger. Moreover, jury trials introduced the risk of local sympathy or acquittal, particularly when defendants were respected figures or when accusations rested on interpretation rather than fact. For a monarchy concerned with preemption rather than remediation, such uncertainty was intolerable.

The Tudor state gravitated toward mechanisms that could bridge the gap between suspicion and punishment. Governance required tools capable of addressing potential threats before they crystallized into rebellion. This need did not arise from paranoia alone, but from structural vulnerability. A regime still consolidating its authority could not afford to tolerate unchecked challenges to its image or intentions. The political order evolved toward legal flexibility, interpretive enforcement, and discretionary power, setting the stage for extraordinary courts and the redefinition of dissent as a matter of state security rather than public debate.

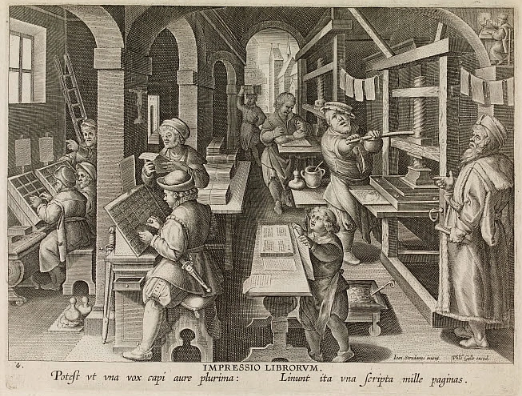

The Rise of Print and the New Politics of Information

International Printing Museum, Wikimedia Commons

The arrival of print in England did not merely increase the volume of texts in circulation. It altered the political meaning of communication itself. Before the spread of printing presses, political discourse moved slowly through sermons, proclamations, manuscript exchange, and oral rumors. These channels were limited by geography, literacy, and social hierarchy, and they allowed authority to remain spatially and socially anchored. Print disrupted these constraints. Once texts could be reproduced cheaply and disseminated widely, political commentary was no longer confined to elite circles or localized audiences. Information acquired durability and reach that fundamentally challenged older assumptions about how authority was encountered and maintained. Words could now outlast events, migrate across regions, and accumulate influence, eroding the Crown’s ability to manage meaning through episodic intervention.

What unsettled Tudor authorities was not the novelty of criticism, but its scalability. A seditious remark spoken in a tavern might fade quickly or be contained through local intervention. A printed pamphlet could travel far beyond its place of origin, be read repeatedly, and circulate among readers unknown to the Crown. Print enabled ideas to persist independently of their authors, severing the link between speech and immediate accountability. This autonomy transformed commentary into a structural phenomenon rather than an isolated act. The state could punish a speaker, but the words themselves continued to speak.

Print also introduced a new kind of political audience. Literacy was expanding unevenly but steadily, particularly among urban populations, merchants, clergy, and artisans. These readers were not passive recipients of royal messaging. They compared texts, interpreted arguments, and shared materials within networks that bypassed official oversight. Pamphlets, ballads, and polemical tracts invited readers to form judgments rather than merely absorb instruction. This participatory dimension of print intensified official concern. Authority was no longer simply issuing commands; it was competing within a contested field of interpretation. Readers became intermediaries in the political process, transmitting ideas through discussion, annotation, and repetition, thereby multiplying the reach of texts beyond the control of their original producers.

The Crown’s response was shaped by an acute awareness that control over information was inseparable from control over legitimacy. Tudor governance relied heavily on symbolism, proclamation, and the moral authority of monarchy. Print threatened to fracture these symbolic monopolies by offering alternative narratives of events, policies, and personalities. Even texts that did not explicitly advocate rebellion could undermine authority by reframing royal actions, questioning motives, or exposing contradictions. The danger lay less in explicit sedition than in the erosion of reverence. Once authority became discussable, it became debatable.

This new informational environment placed unprecedented strain on existing regulatory mechanisms. Licensing systems, guild oversight, and episcopal approval were intended to manage print production, but enforcement was uneven and often reactive. Foreign presses, clandestine printers, and anonymous authors further complicated control. Suppression after publication proved insufficient, as texts often circulated widely before intervention occurred. The state began to conceptualize print not merely as a medium to be regulated, but as a political force requiring preemptive discipline. The focus shifted toward surveillance, anticipatory punishment, and the cultivation of fear within the printing trade itself, encouraging restraint before the press ever reached ink and paper.

The rise of print forced a conceptual shift in how power understood speech. Political danger was no longer limited to action or incitement. It resided in circulation, interpretation, and accumulation. Texts did not need to call for rebellion to be destabilizing. They needed only to persist, invite judgment, and multiply beyond the state’s line of sight. The sheer volume of printed material created an environment in which authority could no longer plausibly claim singular narrative control. This recognition marked a turning point in the relationship between authority and communication. Print did not simply expand the public sphere. It compelled the state to reconceive information itself as a domain of governance.

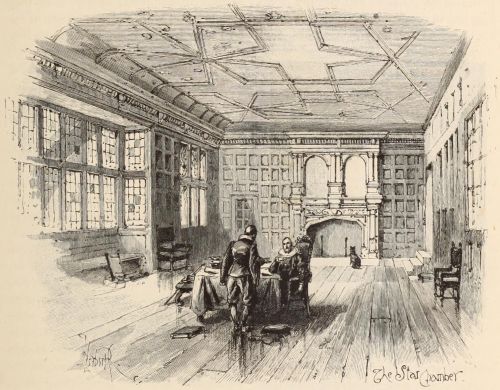

The Star Chamber: Structure, Purpose, and Legal Exceptionalism

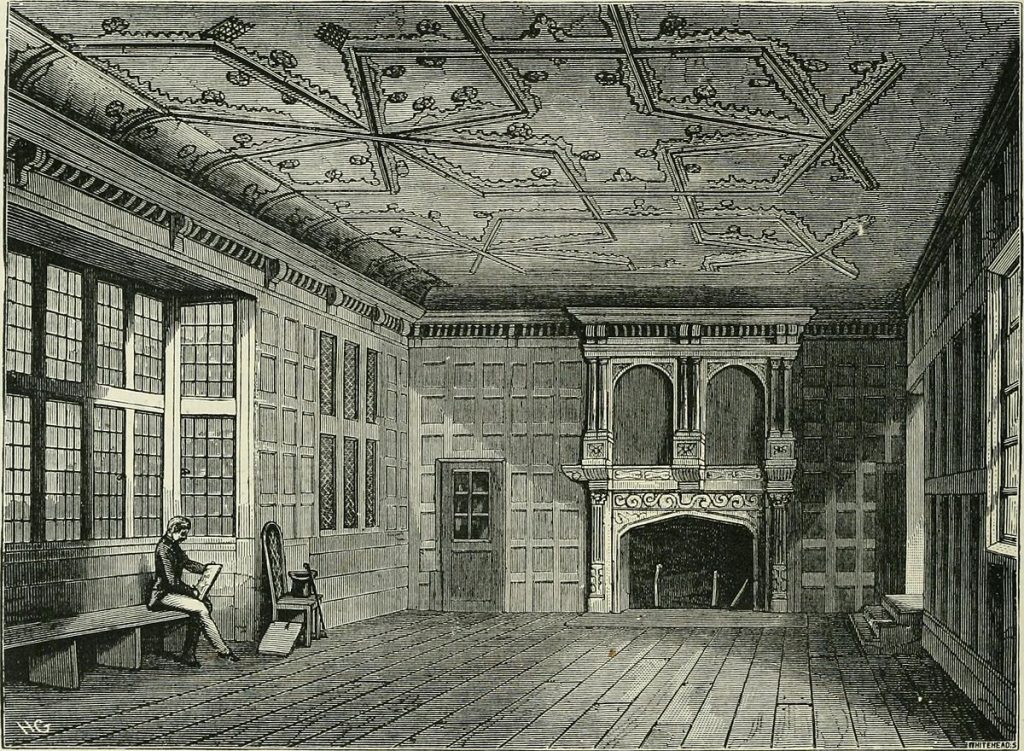

The Star Chamber occupied a peculiar position within the Tudor legal system. Formally, it was not an aberration but an extension of royal authority grounded in medieval precedent. Its roots lay in the king’s council, which had long exercised discretionary power in matters touching the security of the realm. Under the Tudors, however, the Star Chamber evolved into a distinct judicial body with a defined institutional identity and an expanding remit. It became a forum where the Crown could address politically sensitive cases without the constraints imposed by common law procedure.

What distinguished the Star Chamber most sharply from common law courts was its freedom from juries. Proceedings were conducted by privy councillors and senior judges, individuals whose loyalty to the Crown was assumed and whose judgments were shaped by considerations of state rather than local sentiment. This structure eliminated the unpredictability associated with jury trials, particularly in cases involving prominent figures, popular defendants, or ambiguous acts of dissent. Juries drawn from local communities could be swayed by sympathy, shared grievances, or fear of reprisal, making them unreliable instruments for enforcing politically sensitive judgments. By removing juries from the equation, the Star Chamber ensured that interpretation of speech and intent rested firmly in the hands of the political elite, aligning legal outcomes with royal priorities rather than communal opinion.

The court’s procedural flexibility further enhanced its utility. The Star Chamber was not bound by strict evidentiary rules, nor did it require the demonstration of overt criminal acts. It could consider rumor, implication, and inferred intent as grounds for judgment. Interrogation under oath allowed authorities to probe not only what defendants had done, but what they had meant, believed, or encouraged others to believe. This emphasis on interpretation rather than action made the court uniquely suited to policing speech, particularly printed or circulated material whose effects were diffuse and difficult to quantify. In this setting, silence, tone, and association could be treated as evidence, enabling the state to punish perceived threats before they materialized as open resistance.

Punishments imposed by the Star Chamber reinforced its deterrent power. Fines, imprisonment, public humiliation, and corporal penalties such as the pillory were designed to be visible as well as punitive. These sanctions rarely aimed at eliminating offenders entirely. Instead, they functioned as warnings to broader communities, especially printers, writers, and booksellers. The spectacle of punishment communicated the boundaries of permissible expression more effectively than abstract legal doctrine ever could.

Crucially, the Star Chamber maintained the appearance of legality even as it operated beyond ordinary legal safeguards. Defendants were charged, hearings were conducted, and judgments were recorded, creating a paper trail that mimicked the processes of conventional courts. This procedural formality allowed repression to present itself as justice rather than arbitrary violence. The Crown could claim that order was being maintained through law, not through personal vendetta or despotic whim. This mattered deeply in a political culture that still valued the symbolism of lawful governance. By embedding exceptional power within recognizable legal forms, the state normalized repression and reduced the likelihood of overt resistance to its authority.

The Star Chamber’s importance lay not merely in the cases it adjudicated but in the model of authority it embodied. It demonstrated how legal exceptionalism could be normalized when framed as necessity. By creating a space where political speech could be punished without dismantling the legal system as a whole, the Tudor state established a durable mechanism for managing dissent. The court’s very existence signaled that certain forms of expression lay beyond the protection of ordinary law, a principle that would echo through later debates over emergency powers, national security, and the limits of permissible criticism.

Writers, Printers, and Pamphleteers as Political Threats

In the Tudor imagination, the danger posed by dissent increasingly resided not only in what was said, but in who enabled its circulation. Writers, printers, and pamphleteers occupied distinct roles within the emerging information economy, yet Tudor authorities often treated them as a single category of threat. Authorship mattered, but production mattered more. A seditious idea confined to a private manuscript posed limited risk. The same idea multiplied through print could destabilize reputation, invite imitation, and erode obedience across social boundaries. The Crown learned to view the machinery of publication itself as politically consequential.

Printers, in particular, attracted sustained scrutiny because they represented the material hinge between ideas and audiences. Unlike authors, who could claim intellectual abstraction or rhetorical ambiguity, printers dealt in tangible objects that could be seized, counted, and traced. The printing press made dissent reproducible, and reproducibility made it governable through punishment. Tudor policy increasingly targeted printers as responsible agents, holding them accountable for the content they produced regardless of authorship. This strategy had a chilling effect that extended far beyond individual prosecutions. By making printers legally vulnerable, the state transformed them into risk managers, forcing commercial decisions to double as political judgments. Printers learned to anticipate danger, refusing texts that might attract attention and internalizing the logic of censorship long before any official intervention occurred.

Pamphleteers occupied a more ambiguous position. Often anonymous or pseudonymous, they exploited the speed and flexibility of print to respond quickly to political events. Pamphlets blurred the line between information and interpretation, offering commentary that could be framed as explanation rather than agitation. This ambiguity made them particularly unsettling to authorities. Pamphlets did not need to call for rebellion to be effective. They could undermine confidence, question motives, or expose contradictions through tone alone. Their immediacy allowed them to circulate widely before official responses could be coordinated, while their accessibility invited readers of varying education and status into political interpretation. In this sense, pamphleteers democratized commentary in ways that bypassed traditional hierarchies of voice and authority.

The Tudor state responded by expanding the scope of responsibility beyond direct authorship. Possession, distribution, and even failure to report suspect material could attract scrutiny. Writers were interrogated not only about what they had written, but about whom they knew, where texts had circulated, and what audiences might infer. Printers were expected to know the content of what they produced, even when texts were submitted under pressure or disguise. This expansion of liability transformed participation in print culture into a calculated risk, encouraging self-censorship at every stage of production.

Punishment served both corrective and instructional purposes. Fines and imprisonment removed individuals temporarily from circulation, but public penalties communicated lessons to the wider community. The aim was not total suppression of print, which was neither practical nor desirable, but discipline. Writers learned to soften language, printers learned to refuse contentious material, and readers learned to associate certain kinds of curiosity with danger. This environment reshaped the culture of publication itself, narrowing the range of permissible commentary without the need for constant intervention.

The treatment of writers, printers, and pamphleteers reveals how Tudor censorship functioned less as a blunt instrument than as a system of incentives and deterrents. By targeting the intermediaries of communication, the state extended its reach beyond individual texts to the conditions under which texts were produced. Political speech was not eliminated, but regulated through fear, uncertainty, and selective enforcement. This system encouraged compliance without requiring omnipresent surveillance, embedding discipline within ordinary professional practice. In doing so, the Tudor regime transformed the infrastructure of print into an extension of governance itself, ensuring that control over information was exercised not only through law, but through the daily decisions of those who made publication possible.

Sedition Redefined: From Violence to Interpretation

In Tudor England, sedition underwent a critical transformation. Traditionally, seditious behavior had been understood in terms of action. Rebellion, riot, and armed resistance constituted clear threats to political order and could be addressed through existing legal frameworks. By the sixteenth century, however, the locus of danger shifted. The Crown increasingly treated interpretation itself as a site of political risk. Speech, writing, and even insinuation could be construed as seditious if they encouraged subjects to question royal authority or reinterpret the legitimacy of governance.

This redefinition reflected the realities of an emerging information society. Printed texts rarely incited immediate violence, yet they shaped perceptions over time in ways that authorities found deeply unsettling. A pamphlet that questioned policy or mocked royal figures might not provoke rebellion, but it could weaken habits of deference and normalize skepticism among readers. Tudor officials began to judge speech not by its explicit content alone, but by its presumed consequences. Meaning became a matter of inference rather than declaration. Tone, context, circulation patterns, and imagined audience reception all entered legal consideration. In this framework, a text’s danger lay not in what it said outright, but in what it might encourage others to think, discuss, or doubt.

The legal elasticity of sedition proved especially useful in extraordinary courts. Within the Star Chamber, judges could infer malicious intent from rhetorical choices, metaphors, or patterns of dissemination. Defendants were required to account not only for what they had written, but for how their words might reasonably be understood by others. This inversion placed speakers in an impossible position. Innocence could not be established through denial alone, because the alleged harm resided in the interpretive space between text and reader. Even disclaimers of loyalty offered little protection if officials concluded that a work invited dangerous conclusions. By treating political meaning as inherently volatile, the state transformed ambiguity itself into liability.

This shift had profound consequences for political culture. Once sedition was detached from violence, any public commentary became potentially prosecutable. The boundaries of acceptable speech narrowed, not through comprehensive bans, but through uncertainty and selective enforcement. Writers and readers alike learned that interpretation carried risk, and that the safest course was restraint. In redefining sedition as a matter of meaning rather than action, the Tudor regime constructed a durable framework for suppressing dissent while preserving the outward forms of lawful order.

Star Chamber as Political Theater and Deterrence

The Star Chamber functioned not only as a judicial body but as a carefully staged instrument of political instruction. Its proceedings were meant to be seen, discussed, and remembered. Trials involving writers, printers, or pamphleteers were selected precisely because their outcomes could resonate beyond the courtroom. The Crown understood that punishment worked most effectively when it taught a lesson to observers rather than merely correcting individual offenders. In this sense, the Star Chamber transformed law into performance, using judicial ritual to dramatize the consequences of dissent.

Publicity played a central role in this process. Although Star Chamber hearings were not open in the modern sense, their outcomes circulated widely through rumor, correspondence, and printed reports. Sentences such as heavy fines, imprisonment, or corporal punishment were designed to attract attention and provoke caution. The visibility of penalties mattered more than their severity. A single well-publicized punishment could discipline an entire community of printers more effectively than dozens of private warnings. News of these judgments traveled along the same informal networks as pamphlets themselves, ensuring that the message of deterrence reached precisely those most likely to test the boundaries of permissible speech.

Deterrence also relied on selectivity. The Star Chamber did not prosecute every instance of questionable speech, nor could it have done so without overwhelming its own capacity. Instead, it chose cases that would maximize symbolic impact. Well-known figures, repeat offenders, or cases involving topical controversies were especially attractive. This selective enforcement created uncertainty rather than clarity. Because punishment was neither universal nor predictable, writers and printers could never be sure which texts might trigger prosecution. The absence of fixed thresholds encouraged caution, fostering a culture in which restraint became a rational response to legal ambiguity rather than an imposed rule.

The theatrical dimension of punishment extended beyond the courtroom into public space. Penalties such as the pillory or public shaming transformed individual bodies into warnings, embedding the lesson of obedience within everyday experience. These spectacles linked speech to physical consequence, reinforcing the idea that words could inflict harm upon the state and warranted bodily discipline. Even when punishment did not involve corporal display, the reputational damage inflicted by Star Chamber judgments could be severe. Conviction marked individuals as disloyal or dangerous, limiting future opportunities and isolating them within professional and social networks long after formal penalties had ended.

The Star Chamber demonstrated how repression could operate efficiently through example rather than saturation. Political order was maintained not by silencing every voice, but by shaping the expectations of those who might speak. The court’s theatrical logic allowed the Tudor state to conserve resources while extending its influence deep into the culture of print. Law became not merely a mechanism of enforcement, but a medium of communication, transmitting warnings about the limits of criticism and the costs of transgression.

Star Chamber as Political Theater and Deterrence

The Star Chamber’s effectiveness rested on its ability to turn enforcement into instruction. Punishment was calibrated not simply to correct an offender, but to educate a watching audience. Even when proceedings themselves were limited in access, their outcomes circulated quickly through correspondence, rumor, and the very print networks the court sought to discipline. This diffusion was intentional. The Crown relied on visibility to magnify the effects of each case, ensuring that the meaning of punishment extended well beyond the individual before the court.

Selective prosecution amplified this effect. The Star Chamber did not attempt comprehensive suppression, which would have been impractical and politically costly. Instead, it targeted cases that carried symbolic weight. Writers or printers associated with topical controversies, religious tension, or popular readerships were especially vulnerable. This strategy produced uncertainty rather than clarity. Because enforcement appeared episodic and discretionary, it discouraged actors from assuming safety through precedent or consistency. No clear threshold of acceptability emerged, only a sense that punishment could arrive unpredictably. This uncertainty reshaped behavior across the entire information ecosystem. Writers learned that prior tolerance offered no guarantee of future safety, printers learned that past compliance did not confer immunity, and readers learned that attention itself could be risky. Ambiguity became a governing tool, prompting widespread self-regulation where explicit prohibition might have failed, and encouraging silence as a rational response to legal indeterminacy.

Public penalties reinforced this theatrical logic. Corporal punishment, fines, and imprisonment were not merely sanctions but signals. When offenders were displayed, shamed, or financially ruined, their bodies and livelihoods became cautionary texts. Even non-corporal judgments carried lasting reputational consequences. Conviction marked individuals as politically suspect, discouraging association and narrowing future opportunities. In this way, deterrence extended temporally as well as socially, shaping behavior long after formal sentences ended.

Through performance and example, the Star Chamber demonstrated how law could communicate power as effectively as it enforced it. Authority was maintained not by omnipresent surveillance, but by strategic display. The court’s theater taught subjects where the boundaries lay and what awaited those who crossed them. By embedding deterrence within ritual, reputation, and rumor, the Tudor state cultivated compliance without requiring constant intervention. Law became a language through which power spoke indirectly, shaping expectations, disciplining imagination, and ensuring that fear and anticipation performed much of the work that overt coercion alone could not sustain.

From Tudor England to Modern Press Suppression

The mechanisms developed in Tudor England to manage dissent did not vanish with the abolition of the Star Chamber in the seventeenth century. Instead, they provided a durable template for how states could suppress political speech while maintaining the outward forms of legality. What endured was not a specific court, but a governing logic that treated communication as a problem of security rather than expression. When governments confront speech they perceive as destabilizing, they often reach first for legal instruments rather than overt force. Law offers legitimacy, continuity, and deniability. The Tudor experience demonstrates how repression can be normalized when framed as procedural necessity, administrative discipline, or the neutral enforcement of order rather than as political retaliation against critics.

One of the most enduring continuities lies in the use of law to redefine harm. Just as Tudor authorities expanded sedition from violent action to dangerous interpretation, modern states frequently broaden legal categories to encompass speech that undermines public order, national security, or institutional trust. Journalists, commentators, and publishers may find themselves targeted not for inciting violence, but for shaping narratives deemed corrosive or destabilizing. The emphasis shifts from what is done to what is implied, inferred, or received by an audience. Meaning itself becomes actionable. While the language has changed, the structure remains familiar. Interpretation, implication, and presumed effect continue to serve as grounds for legal scrutiny, allowing states to discipline speech without openly rejecting commitments to press freedom.

Selective enforcement also persists as a defining feature. Modern governments rarely attempt comprehensive suppression, which would invite resistance and expose authoritarian intent. Instead, they pursue highly visible cases that generate deterrent effects far beyond their immediate scope. Criminal charges, civil suits, regulatory penalties, or prolonged legal harassment serve as warnings to others operating in adjacent spaces. As in Tudor England, unpredictability amplifies fear. When boundaries are unclear and enforcement appears discretionary, self-censorship becomes a rational and even necessary strategy for survival. The result is a narrowing of permissible discourse achieved through anticipation rather than prohibition.

Another continuity lies in the targeting of intermediaries. Just as Tudor authorities focused on printers, booksellers, and distributors, modern regimes often exert pressure on platforms, publishers, and institutional gatekeepers. Legal liability is shifted outward, encouraging private actors to police speech preemptively in order to avoid risk. This diffusion of responsibility allows the state to distance itself from direct censorship while still shaping the information environment. Control is exercised through licensing regimes, compliance requirements, content moderation mandates, and the threat of punitive action. As in the Tudor period, governance operates most effectively when intermediaries internalize the logic of repression and enforce it themselves.

The Tudor case offers more than historical analogy. It reveals a recurring pattern in the relationship between power and communication. When new technologies expand the reach and speed of speech, states respond by adapting legal frameworks to contain interpretation rather than silence expression outright. The suppression of dissent proves most effective when it appears lawful, selective, and justified by necessity. Tudor England reminds us that press suppression rarely announces itself as tyranny. It advances quietly, through courts, procedures, and the steady redefinition of what speech is allowed to mean.

Conclusion: When Law Becomes the Enemy of Speech

The history of the Star Chamber demonstrates that repression does not require the abandonment of law. On the contrary, it often depends upon law’s adaptability. Tudor England did not silence dissent through arbitrary terror alone, but through courts, procedures, and doctrines that redefined the boundaries of permissible speech. By treating interpretation as danger and circulation as threat, the state transformed ordinary acts of communication into matters of political security. Law did not merely respond to dissent. It reshaped the conditions under which dissent could exist at all. In doing so, it created a political environment in which speech was regulated not by explicit prohibition, but by the anticipation of legal consequence. The most effective constraint was not punishment itself, but the internalization of risk, as writers and printers learned to navigate an ever-shifting landscape of implied limits.

What makes this history unsettling is not its distance from the present, but its familiarity. The Tudor regime justified its actions as necessary for stability, order, and the preservation of authority in a changing world. These justifications recur whenever states confront speech that challenges dominant narratives or exposes institutional vulnerability. By expanding legal categories, targeting intermediaries, and enforcing selectively, governments can suppress criticism while maintaining a public commitment to legality. The appearance of due process becomes a shield behind which repression advances incrementally.

The Star Chamber’s legacy reminds us that freedom of expression is most endangered not when law collapses, but when it is repurposed. Exceptional courts, emergency powers, and interpretive doctrines allow states to discipline speech without overt censorship. Uncertainty replaces prohibition as the primary instrument of control. Writers, journalists, and publishers learn to anticipate risk, moderating themselves in response to legal ambiguity rather than explicit bans. In such environments, silence is not imposed. It is chosen.

When law becomes the enemy of speech, it does so quietly and incrementally. It speaks the language of necessity, protection, and order while steadily narrowing the space in which criticism can safely operate. Tudor England shows how easily repression can be embedded within legal form and institutional routine, insulated from challenge by its own procedural legitimacy. The lesson is not that law inevitably corrupts freedom, but that it can be made to serve power as readily as principle. The defense of speech therefore requires more than constitutional language or formal rights. It requires sustained vigilance against the subtle transformation of law itself into a mechanism for punishing interpretation, discouraging scrutiny, and rendering dissent legally precarious even when it remains nominally permitted.

Bibliography

- Bellamy, John G. The Tudor Law of Treason. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

- Clegg, Cyndia Susan. Press Censorship in Elizabethan England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Dripps, Donald A. “The ‘Cruel and Unusual’ Legacy of the Star Chamber.” Journal of American Constitutional History 2:1 (2023): 139-229.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Elton, G.R. “Presidential Address: Tudor Government: The Points of Contact. III. The Court.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 26 (1976): 211-228.

- Galley, Chris. “A Model of Early Modern Urban Demography.” The Economic History Review 48:3 (1995): 448-469.

- Ginsberg, Warren. The Cast of Character: The Representation of Personality in Ancient and Medieval Literature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983.

- Guy, John. The Court of Star Chamber and Its Records to the Reign of Elizabeth I. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1985.

- —-. Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Hadfield, Andrew. Literature and Censorship in Renaissance England. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

- Halliday, Paul D. Habeas Corpus: From England to Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Lake, Peter, and Steven Pincus, eds. The Politics of the Public Sphere in Early Modern England. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007.

- Loades, David. Politics and the Nation, 1450–1660. Oxford: Blackwell, 1974.

- —-. “The Press under the Early Tudors: A Study in Censorship and Sedition.” Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 4:1 (1964): 29-50.

- —-. The Tudor Court. London: Batsford, 1986.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Later Reformation in England, 1547–1603. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1990.

- Pettegree, Andrew. The Book in the Renaissance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Post, Robert C. Democracy, Expertise, and Academic Freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012.

- Sharpe, J. A. Crime in Early Modern England 1550–1750. London: Longman, 1984.

- —-. Early Modern England: A Social History 1550–1760. London: Edward Arnold, 1987.

- —-. Judicial Punishment in England. London: Faber and Faber, 1990.

- Skinner, Quentin. The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, Volume 2: The Age of Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Williams, Penry. The Tudor Regime. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979.

- Zaret, David. Origins of Democratic Culture: Printing, Petitions, and the Public Sphere in Early-Modern England. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.02.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.