If Reconstruction was the birth of a more expansive democracy, then the White League and Red Shirts were its assassins. Not only did they silence voices, they rewrote the rules of who could speak.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Specter of the Lost Cause

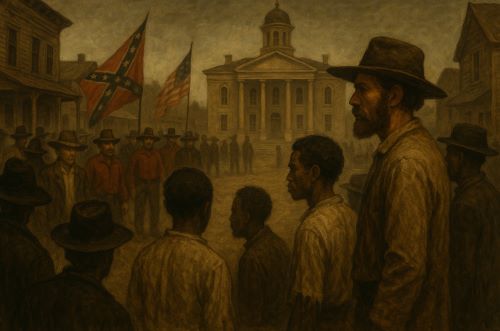

In the fragile years following the American Civil War, the defeated Confederacy did not vanish into submission. Instead, it metastasized. The battlefield loss of the Southern cause gave way to an ideological insurgency, fueled by bitterness, bolstered by white supremacy, and determined to reclaim political dominance by whatever means necessary. In this twilight of Reconstruction, the rifle and the ballot box would merge into a singular instrument of power.

The story of Reconstruction is often narrated as a tragic retreat from the radical promise of Black citizenship and multiracial democracy. That narrative is not wrong, but it is incomplete. The rollback of Reconstruction was not merely the result of political compromise or federal fatigue. It was a coordinated campaign of racial terror, executed in part by organized paramilitary groups who blended the aesthetics of war with the tactics of politics. Among the most notorious were the White League and the Red Shirts.

This essay traces the rise, methods, and ideological function of these groups in the postwar South. More than footnotes in the history of white backlash, they were foundational actors in the reassertion of white rule. Their story is not just one of violence, but of legitimacy sought through intimidation. To study them is to confront the fragility of democracy when its institutions become porous to coercion.

The White League: A Shadow Army in the Garb of Citizenship

Louisiana as Laboratory of Counter-Revolution

The White League was born in Louisiana in 1874, a state emblematic of both radical Reconstruction and violent resistance to it. Composed largely of Confederate veterans and members of the Democratic Party elite, the League presented itself as a civic militia dedicated to “redeeming” the South from Republican and Black political control. It operated in daylight, with open affiliation and public support from Southern newspapers and politicians.1

Its methods, however, were drawn from a deeper well of antebellum coercion. The League targeted Black voters, white Republicans, and federal authorities with calculated assaults that escalated in precision and brutality. The massacre in Coushatta, where six Republican officeholders were murdered after being forced to resign, sent a chilling message: governance under Reconstruction would be punished with death.2

The League’s most dramatic moment came with the Battle of Liberty Place in September 1874. Nearly five thousand members, armed and organized, attempted a coup in New Orleans, deposing the Republican governor for several days before federal troops restored order.3 The incident was less a failure than a warning. The federal government’s reluctance to prosecute participants signaled waning resolve and emboldened further rebellion.

Respectability, Violence, and the Illusion of Legality

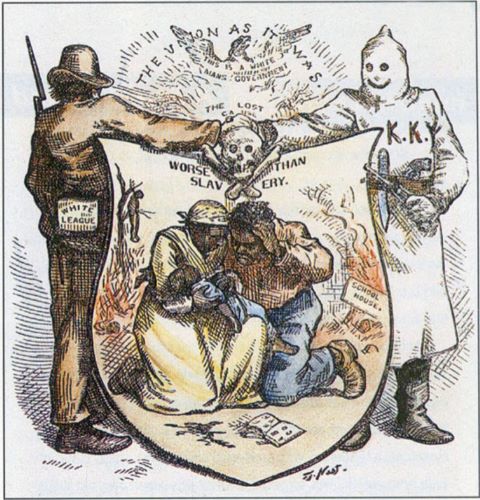

What distinguished the White League from the clandestine Ku Klux Klan was its strategic visibility. Members held public rallies, issued formal statements, and openly coordinated with Democratic candidates. It portrayed its mission not as insurrection but as restoration. This veneer of respectability made it more dangerous. The League normalized the idea that extralegal violence could be a civic virtue when directed toward the preservation of racial order.

This tactic blurred the line between state and mob. In many towns, local sheriffs and officials were themselves League members or beholden to its influence. When violence occurred, investigations were tepid or absent. The League did not merely bypass the law—it infiltrated it.4

The Red Shirts: Spectacle and Suppression in the Carolinas

From South Carolina to Mississippi: A Uniform of Intimidation

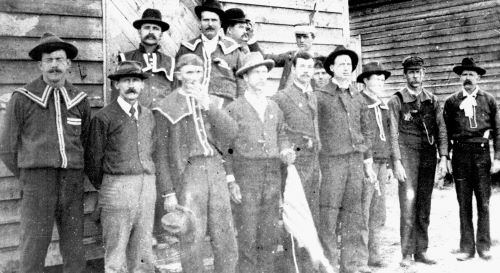

The Red Shirts emerged shortly after the White League, primarily in South Carolina, and expanded rapidly into North Carolina and Mississippi. Like their counterparts, they were organized and ideologically coherent. They adopted red garments not just for identification, but for theatrical intimidation. Their marches and rallies were deliberately militaristic, often timed to coincide with Republican campaign events.5

They pioneered what might be called the choreography of terror. By appearing en masse in rural Black communities, often on horseback, they turned everyday political activity into a battlefield. Armed presence was not incidental. It was the message.

The Red Shirts’ greatest triumph came during the South Carolina gubernatorial campaign of 1876. Through coordinated voter suppression, assassination, and relentless public harassment, they ensured the victory of Wade Hampton III, a Confederate general turned Redeemer politician.6 The Democratic claim to have won through “peaceful persuasion” was a bitter farce. The ballot had become indistinguishable from the bullet.

The Performance of Order and the Collapse of Federal Resolve

What made the Red Shirts particularly effective was their manipulation of appearance. They did not conceal their actions. On the contrary, they invited public recognition, even acclaim. Newspapers sympathetic to the cause painted them as patriots, misunderstood men seeking peace through stability. The Red Shirts inverted the moral lens, framing Black political participation as disorder and white paramilitary coercion as guardianship.

This inversion found tacit endorsement from a war-weary North. As the federal government turned inward and Reconstruction fatigue grew, intervention declined. By 1877, with the Compromise that ended Reconstruction, federal troops withdrew from the South, leaving Black communities exposed and unprotected.7

The Red Shirts did not disband. They simply evolved into the new normal. Their leaders became senators, governors, and sheriffs. Their methods, meanwhile, were institutionalized through literacy tests, poll taxes, and Jim Crow segregation. What they began with rifles and spectacle, they completed with bureaucracy.

Ideological Convergence: Paramilitary Politics and the Cult of Redemption

Memory, Myth, and the Weaponization of the Past

Both the White League and the Red Shirts were products of a particular Southern obsession: the Lost Cause. In this narrative, the Civil War was not a rebellion but a noble stand for local autonomy, and Reconstruction was a humiliation inflicted by foreign occupiers and corrupt Black governments. This mythology served as a moral foundation for violence.

Paramilitary groups did not operate in ideological vacuum. They were heirs to a culture that sanctified resistance and baptized racial supremacy in historical grievance. Their members invoked the language of honor, duty, and preservation, cloaking their terrorism in the vocabulary of patriotism.8

This myth-making was generative. It produced public memory, monuments, and textbooks that cast Redeemers as saviors rather than saboteurs of democracy. Through it, the White League and Red Shirts were written into Southern lore not as criminals, but as tragic heroes.

Toward a Theory of White Paramilitary Democracy

The White League and Red Shirts reveal a paradox at the heart of American democracy: its openness can be weaponized by those who do not believe in its fundamental premises. These groups understood elections, not as expressions of pluralism, but as theaters for power reclamation. They used political language while nullifying political rights.

The long arc of this strategy did not end in the 1870s. It set precedent. Across American history, from the Wilmington Coup of 1898 to the modern echoes of militia movements, the shadow of paramilitary democracy persists. The lesson is not simply that democracy can be dismantled from within. It is that it can be dressed in its own garments as it is undone.

Conclusion: Rifles at the Polls, and the Fragility of the Franchise

To study the White League and the Red Shirts is to examine a moment when violence was not merely adjacent to politics; it was politics. Their actions did not occur in the shadows, but in broad daylight, with the consent or complicity of institutions meant to defend the republic. They succeeded not because they were invincible, but because the will to stop them dissolved.

Their legacy is not frozen in the past. It lives in every effort to use fear as a tool of governance, every movement that treats pluralism as contamination. The rifle at the polling place, literal or metaphorical, remains a symbol of American vulnerability.

If Reconstruction was the birth of a more expansive democracy, then the White League and Red Shirts were its assassins. Not only did they silence voices, they rewrote the rules of who could speak.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 58–63.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 550.

- Justin A. Nystrom, New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), 109–113.

- Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 52.

- Bruce E. Baker, What Reconstruction Meant: Historical Memory in the American South (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), 77.

- Stephen Budiansky, The Bloody Shirt: Terror after Appomattox (New York: Viking, 2008), 143–145.

- Heather Cox Richardson, To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 102–106.

- Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 99–101.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Carol. White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Baker, Bruce E. What Reconstruction Meant: Historical Memory in the American South. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009.

- Budiansky, Stephen. The Bloody Shirt: Terror after Appomattox. New York: Viking, 2008.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Foster, Gaines M. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Lemann, Nicholas. Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Nystrom, Justin A. New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

- Richardson, Heather Cox. To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.