Women who followed various paths to their wartime assignments.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

World War II opened a new chapter in the lives of Depression-weary Americans. As husbands and fathers, sons and brothers shipped out to fight in Europe and the Pacific, millions of women marched into factories, offices, and military bases to work in paying jobs and in roles reserved for men in peacetime.

For female journalists, World War II offered new professional opportunities. Talented and determined, dozens of women fought for–and won–the right to cover the biggest story of their lives. By war’s end, at least 127 American women had secured official military accreditation as war correspondents, if not actual front-line assignments. Other women journalists remained on the home front to document the ways in which the country changed dramatically under wartime conditions.

This article spotlights eight women who succeeded in “coming to the front” during the war–Therese Bonney, Toni Frissell, Marvin Breckinridge Patterson, Clare Boothe Luce, Janet Flanner, Esther Bubley, Dorothea Lange, and May Craig. Their stories–drawn from private papers and photographs primarily in Library of Congress collections–open a window on a generation of women who changed American society forever by securing a place for themselves in the workplace, in the newsroom, and on the battlefield.

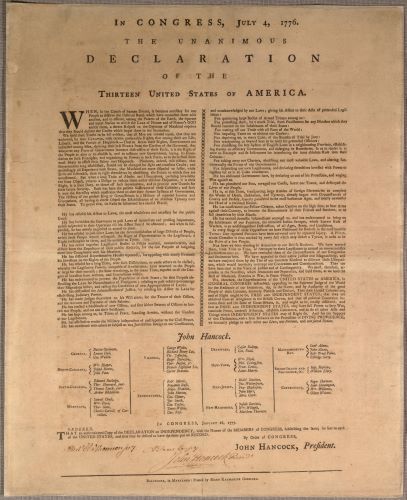

Two Centuries of American Women Journalists

The women journalists, photographers, and broadcasters of World War II followed two centuries of trailblazers. During the 1700s, Mary Katherine Goddard, Anne Royall, and other women ran family printing and newspaper businesses along the East Coast. By the late 1800s, the growth of higher education for women had spawned a new market–and jobs–for writers of “women’s news.”

At the turn of the twentieth century, the woman’s suffrage movement opened opportunities for female reporters to cut their teeth on national politics under the guise of women’s news. However, female reporters often worked without permanent office space, salaries, or access to the social clubs and backrooms where men conducted business. In response, women began their own professional associations, such as the Women’s National Press Club, founded on September 27, 1919, by a group of Washington newswomen. The organization eventually merged with the National Press Club after it admitted women in 1971.

When the Great Depression threatened the tenuous foothold of women on newspaper staffs, Eleanor Roosevelt instituted a weekly women-only press conference to force news organizations to employ at least one female reporter. During World War II, many of the newswomen in the First Lady’s circle served as war correspondents.

Those who did get to the war front followed a path begun a century earlier by pioneers such as Margaret Fuller (the New York Herald Tribune’s European correspondent in the 1840s), Jane Swisshelm (Civil War), Anna Benjamin (Spanish-American War), and Dorothy Thompson (overseas correspondent in the 1930s), among others. One of the most important predecessors was Peggy Hull, who on September, 17, 1918, won accreditation from the War Department to become the first official American female war correspondent and who went on to serve as a correspondent during World War II.

Whatever route led them to the hospitals, battlefields, and concentration camps, female reporters found that the war offered an unanticipated opportunity. Political-reporter-turned-war correspondent May Craig best summed up their achievements in a 1944 speech at the Women’s National Press Club:

“The war has given women a chance to show what they can do in the news world, and they have done well.”

Seeds of Change

The Allies’ final push in the spring and summer of 1945 brought World War II to a close. With the war’s end came social and economic pressure in the United States to return to “normalcy”. Actively recruited into “male” careers in wartime, women were expected to make room for returning veterans and male colleagues. The ranks of newswomen thinned out, and seasoned newswomen who had proved their competence faced demotion. By 1968 there were actually fewer female foreign correspondents than in the pre-war years.

In spite of pressure on women to give up their jobs after the war, the seeds of permanent change had been planted. Women began to question social and economic rules and demand equal access to educational and career options. By the 1980s, women had entered professional schools and careers–including journalism–in record numbers.

Like their counterparts in every profession, today’s female journalists have benefitted from the willingness of their predecessors to bend and break rules designed to narrow women’s opportunities. The women who are now at the top of the profession or on their way up the ladder owe a debt to all those earlier women who “came to the front” and cleared the path to success.

Therese Bonney

War’s mindless uprooting of innocent civilians provided the principal subject for photographer Therese Bonney (1894-1978) during World War II. Bonney’s images of homeless children and adults on the backroads of Europe touched millions of viewers in the United States and abroad.

Educated at Berkeley, Harvard, Columbia, and the Sorbonne, Bonney settled in Paris in 1919 to pursue photography and promote cultural exchange between France and the United States. The outbreak of World War II appalled Bonney, who believed the conflict threatened European civilization itself. Of her “truth raids” into the countryside to document the horror of war, Bonney said: “I go forth alone, try to get the truth and then bring it back and try to make others face it and do something about it.”

Not content with publishing solely in mass-circulation newspapers and magazines, Bonney sought other opportunities to present her work. She published the photo-essay books “War Comes to the People” (1940) and “Europe’s Children” (1943) and mounted one-woman shows at the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and dozens of museums overseas. Bonney’s concept for a film about children displaced by war became the Academy Award- winning movie, “The Search” (1948). A media star herself, Bonney was the heroine of a wartime comic book, “Photofighter.”

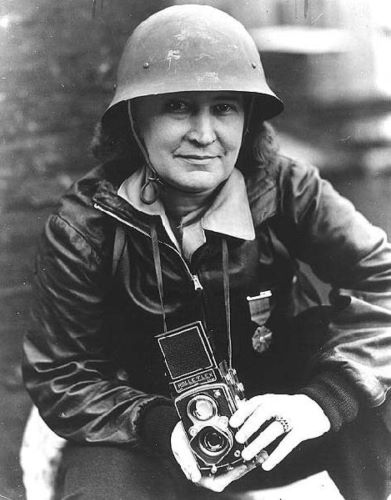

Toni Frissell

Remembered today principally for her high-fashion photography for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, Toni Frissell (1907-1988) volunteered her photographic services to the American Red Cross, Women’s Army Corps, and Eighth Army Air Force during WWII. On their behalf, she produced thousands of images of nurses, front-line soldiers, WACs, African-American airmen, and orphaned children.

Frissell’s leap from fashion photography into war reportage echoed the desires of earlier generations of newswomen to move from “soft news” of fashion and society pages into the “hard news” of the front page. On volunteering for the American Red Cross in 1941, Frissell said: “I became so frustrated with fashions that I wanted to prove to myself that I could do a real reporting job.” Using her connections with high-profile society matrons, Frissell aggressively pursued wartime assignments at home and abroad, often over her family’s objections.

Frissell’s work usually involved creating images to support the publicity objectives of her subjects. Her photographs of WACs in training and under review by President Franklin Roosevelt fit into a media campaign devised to counter negative public perception of women in uniform. Likewise, Frissell’s images of the African American fighter pilots of the elite 332nd Fighter Group were intended to encourage positive public attitudes about the fitness of blacks to handle demanding military jobs.

Marvin Breckinridge Patterson

When World War II broke out in 1939, freelance photojournalist Marvin Breckinridge Patterson (b. 1905) took the first pictures of a London air-raid shelter. She was, however, new to radio when friend Edward R. Murrow hired her as the first female staff broadcaster in Europe for CBS. Before her marriage to an American diplomat ended her career in May 1940, Patterson broadcast fifty times from various locations in Europe, including Berlin.

One of only a handful of American women in Europe working in radio, Patterson was among the first correspondents to use a new short-wave transmitter to broadcast on location. Of her early broadcasts, Murrow told Patterson: “Your stuff so far has been first-rate. I am pleased, New York is pleased, and so far as I know the listeners are pleased. If they aren’t to hell with them.”

Patterson willingly resigned from CBS upon marrying Jefferson Patterson, but hoped to resume her original career in photojournalism. Claiming that her activities would compromise her husband’s work in Berlin, the United States Department of State barred her from publication. Even Patterson’s unofficial efforts to document prisoner-of-war camps while in the company of her husband ended when German officials objected. Frustrated in her efforts to pursue a separate career, Patterson devoted her energies to the role of diplomatic spouse.

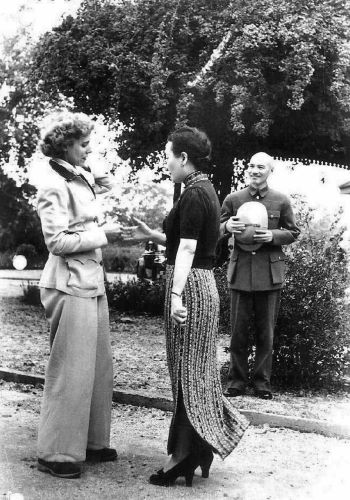

Clare Boothe Luce

Talented, wealthy, beautiful, and controversial, Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987) is best remembered as a congresswoman (1942-1946), ambassador, playwright, socialite, and spouse of magazine magnate Henry R. Luce of Time–Life–Fortune. Less familiar is Luce’s wartime journalism, which included a book, Europe in the Spring (1940) and many on-location articles for Life.

Though she covered a wide range of World War II battlefronts, Luce considered her war reportage merely “time off” from her true vocation as playwright. Nonetheless, Luce endured the discomforts, frustrations, and dangers encountered by even the most seasoned war correspondent. Besides experiencing bombing raids in Europe and the Far East, she faced house arrest in Trinidad by British Customs when a draft Life article about poor military preparedness in Libya proved too accurate for Allied comfort. Luce’s unsettling observations led longtime friend Winston Churchill to revamp Middle Eastern military policy.

Luce’s initial encounter with the war in 1940 produced Europe in the Spring, her first non- fiction book. Anxious to convince fellow Americans of the dangers of isolationism, Luce wrote a vivid, anecdotal account of her four-month visit to “a world where men have decided to die together because they are unable to find a way to live together.”

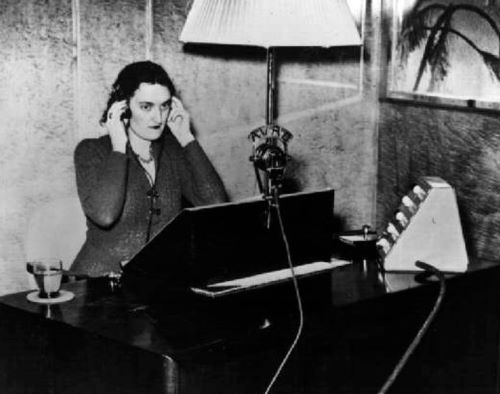

Janet Flanner

Perennial columnist for The New Yorker magazine, Janet Flanner (1892-1978) produced trenchant commentary on European politics and culture. In her mid twenties, Flanner left the United States for Paris, quickly becoming part of the group of American writers and artists who lived in the city between the world wars. In October 1925 Flanner published her first “Letter from Paris” in the then brand-new magazine, The New Yorker, launching a professional association destined to last for five decades.

Flanner’s work during World War II included not only her famous “Letter from Paris” (disrupted for a period) and seminal pieces on Hitler’s rise (1936) and the Nuremburg trials (1945), but a series of little-known weekly radio broadcasts for the NBC Blue Network during the months following the liberation of Paris in late 1944.

Like fellow American expatriate Therese Bonney, Indiana-born Flanner was deeply disturbed by the war’s implications for the future of European civilization. In both her private correspondence and New Yorker column, Flanner often expressed concern over the long-term damage to Europe, noting with despair that “with the material destruction collapsed invisible things that lived within it. . . .”

A master of the printed word, Flanner was less in her element when she crossed the line into broadcast journalism. The need to pursue stories aggressively to justify precious airtime was unsettling to a writer accustomed to mulling over the “big picture.” The ten-minute weekly broadcasts from locations throughout Europe filled Flanner with such anxiety that she relinquished her radio assignment with relief at the end of the war.

Esther Bubley

Military and political events overseas were not the only subjects reporters and photographers covered during World War II. Photographer Esther Bubley (b. 1921) found ample subject matter to explore on the American homefront as the nation mobilized for war.

Twenty-year-old Bubley arrived in Washington, D.C., in 1941, fresh from art school and a short stint with Vogue and eager to earn a living with her camera. Although she soon found work as a lab technician at the National Archives, Bubley’s ambition was to work for Roy Stryker. Stryker, head of the documentary photography project of the Historical Section, Farm Security Administration (FSA) Documentary Photo project from 1935 to 1943, was an outstanding mentor and teacher, who attracted young photographers to work for him.

During her off-hours, Bubley set out to prove her camera skills by snapping wartime subjects around the nation’s capital. Her unvarnished images of life in the city’s boarding houses for war workers impressed Stryker enough to recruit the aspiring photographer into the Office of War Information (OWI), where the Historical Section had been relocated.

OWI sent Bubley on at least one cross-country bus trip, during which she produced hundreds of images of a country in transition from the doldrums of the Great Depression to the fevered pace of war. Unlike many of her colleagues, however, Bubley was not drawn to the awesome industrial complex spawned by the war, preferring instead to focus on average Americans. “Put me down with people, and it’s just overwhelming,” Bubley said of her focus on the human dimension of mobilization.

Dorothea Lange

Like Esther Bubley, Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) documented the change on the homefront, especially among ethnic groups and workers uprooted by the war. Three months after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the relocation of Japanese-Americans into armed camps in the West. Soon after, the War Relocation Authority hired Lange to photograph Japanese neighborhoods, processing centers, and camp facilities.

Lange’s earlier work documenting displaced farm families and migrant workers during the Great Depression did not prepare her for the disturbing racial and civil rights issues raised by the Japanese internment. Lange quickly found herself at odds with her employer and her subjects’ persecutors, the United States government.

To capture the spirit of the camps, Lange created images that frequently juxtapose signs of human courage and dignity with physical evidence of the indignities of incarceration. Not surprisingly, many of Lange’s photographs were censored by the federal government, itself conflicted by the existence of the camps.

The true impact of Lange’s work was not felt until 1972, when the Whitney Museum incorporated twenty-seven of her photographs into Executive Order 9066, an exhibit about the Japanese internment. New York Times critic A.D. Coleman called Lange’s photographs “documents of such a high order that they convey the feelings of the victims as well as the facts of the crime.”

May Craig

A Southerner who made a career working for the Maine-based Gannett newspaper chain, Washington correspondent Elisabeth May Adams Craig (1889-1975) covered World War II with the same keen eye and sharp tongue that informed her daily “Inside in Washington” column for nearly fifty years. When not anchored in the nation’s capital, Craig provided her Maine readership with eyewitness accounts of V-bomb raids in London, the Normandy campaign, the liberation of Paris, and other events.

Craig’s devotion to the news business extended to leadership roles in the Women’s National Press Club and Eleanor Roosevelt’s Press Conference Association, two organizations founded to promote female journalists. The former suffragist also spearheaded countless initiatives to raise the professional status of female news correspondents in the corridors of official power and the capital press corps.

Although Craig herself singlehandedly overturned more than one military rule designed to keep women out of planes and off of ships, even she could not always convince male officials that women could “rough” it if required. Late in her career Craig noted wryly that “Bloody Mary of England once said that when she died they would find `Calais’ graven on her heart” (a reference to a key French outpost lost during Mary’s reign). “When I die, there will be the word `facilities,’ so often it has been used to prevent me from doing what men reporters could do.”

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress to the public domain.