Antiquarianism gave way to archaeology as practitioners turned increasingly to empirical methods.

By Dr. Eleanor Dobson

Associate Professor in Nineteenth-Century Literature

University of Birmingham

Introduction

To pass through the great Central Doorway and enter into the Temple of Sety I is like entering a ‘Time Machine’ of science fiction.1

As Bradley Deane asserts of the ‘lost world’ genre, at its peak between 1871 and 1914, its ‘tales are set on every continent, and judge modern men against the imaginary remnants of almost every people of antiquity and legend’, ‘refiguring the frontier as an uncanny space in which the grand narrative of progress collapses’, and ‘br[inging] Victorian and Edwardian men face to face with their primitive past and challeng[ing] them to measure up’.2 The genre’s heyday, I would add, coincides with the period in which archaeology flourished. The lost- world genre, with its newly identified civilisations often living in subterranean spaces, appears indebted to the burgeoning academic discipline that sought to understand ancient traces excavated from beneath the feet of modern people.

Antiquarianism gave way to archaeology as practitioners turned increasingly to empirical methods in the final decades of the eighteenth century. Across the nineteenth century, landmark excavations stimulated public interest not only in the practice’s discoveries but also in archaeology itself. The Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli (1823–96), who oversaw the excavations at Pompeii from 1863, innovated the filling of voids left by bodies beneath the ash at Pompeii with plaster, making casts that replicated the forms of the ancient dead. A decade later, the German businessman and archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann (1822–90) made the remarkable discovery of the site of Troy. The first modern excavations of the Sphinx at Giza, meanwhile, were supervised by the Italian explorer Giovanni Battista Caviglia (1770–1845) in 1817, with the exposure of the Sphinx’s chest and paws finally achieved in 1887.

We might read a literary echo of such events in narratives that hinge on modern Westerners’ discovery of ‘lost’ civilisations in popular texts such as Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race (1871) and H. Rider Haggard’s She (1886–7). While these civilisations are not direct offshoots of ancient Egypt, they have key Egyptian features. The pyramidal structures beneath the ground and the beautiful sphinx- like features of Bulwer- Lytton’s subterranean people – the Vril-ya – suggest that the author drew some inspiration from ancient Egypt. Meanwhile, Nicholas Daly describes She as ‘in many respects a displaced Egyptian romance’, identifying connections between the novel’s Amahagger people and Victorian attitudes towards modern Egyptians, and between the ruins of Kôr and ancient Egyptian archaeological sites.3 Later, civilisations depicted as explicitly ancient Egyptian in origin were imagined as living beneath the Earth’s surface in several narratives that drew a less ambiguous line between Egyptian archaeology and texts it inspired. Subterranean Egyptian civilisations feature, for example, in Oliphant Smeaton’s (1856–1914) adventure story A Mystery of the Pacific (1899) and Baroness Orczy’s (1865–1947) By the Gods Beloved (1905).

Building from this starting point, in which archaeology is held to have made a particular impact upon the literary imagination at the fin de siècle, this article first addresses encounters with ancient Egypt in lost- world texts, in which offshoots of ancient Egyptian civilisation are imagined as spatially elsewhere, either underground or in another geographically remote location. Such works include Francis Worcester Doughty’s (1850–1917) ‘I’: a story of strange adventure (1887) and Jules Verne’s Le Sphinx des glaces (1897). Next, it scrutinises tales in which ancient Egyptians are imagined existing on the planets closest to Earth, in the British writer and illustrator Fred T. Jane’s To Venus in Five Seconds (1897) and the American astronomer Garrett P. Serviss’s (1851–1929) Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898), in which ancient Egyptians are imagined as having found new homes even further afield. Finally, it turns to texts in which Egypt is not accessed by leaving the planet, but in which Egypt is encountered via time travel, focusing on H. G. Wells’s (1866– 1946) The Time Machine (1895) and E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet (1905–6), before examining the time-travelling ancient Egyptian Rames in William Henry Warner’s (fl. 1919–34) novel The Bridge of Time (1919) and, finally, the astronomer Camille Flammarion’s La Fin du monde (1894). I suggest that these stories of various Egypts, experienced by representatives of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, sprang from a constellation of popular scientific interests in the latter half of the nine-teenth century that crystallised around archaeology: namely, geology and astronomy. These sciences were themselves of intense fascination to occultists, who proposed new theories concerning the history of the Earth based upon findings of practitioners working in these fields, among them an influential hypothesis that Egyptian civilisation was an offshoot of the fabled utopia of Atlantis. Egypt, so often representative of the distant past, typically re-emerges as something futuristic in these texts, with its most recognisable monuments – the pyramids and the Great Sphinx – repeatedly called upon to imagine the distant future, and even the end of humanity itself.

Egypt Elsewhere

While disproven in the eighteenth century, seventeenth- century geological theories of a hollow earth had a significant cultural afterlife in nineteenth- century literature, in which subterranean civilisations – often with an ancient Egyptian or Atlantean origin – proliferated. That these communities have ancient Egyptian links might be attributed in part to public fervour for archaeology, which, over the course of the nineteenth century, brought the remnants of this civilisation to light, often for public consumption in museums. That Egyptology was emerging as a late nineteenth- century science is discernible, for instance, in the regular inclusion of Egyptological pieces in journals such as the British astronomer Richard A. Proctor’s (1837–88) Knowledge: an illustrated magazine of science, founded in 1881. Geological reassessments of the age of the Earth had monumental implications for the study of the ancient world, also suggesting a far greater span of time in which humankind had existed on Earth. Authors rose to the challenge of imagining alternate histories that challenged mainstream archaeological understandings of some of the oldest human civilisations celebrated in modern culture.

Indeed, archaeology seems to have directly inspired several ‘lost world’ stories featuring Egyptian or Egyptian- esque civilisations. Several such tales use frame narratives that foreground an ancient artefact or manuscript as in She, giving such narratives a distinct archaeological flavour.4 The American writer Francis Worcester Doughty’s ‘I’: a story of strange adventure (1887), serialised under the pseudonym Richard R. Montgomery in The Boys of New York, is, for instance, evidently based on She in parts, and substitutes the ancient potsherd with its many scripts (including Egyptian hieroglyphs) for an ivory tablet on which Arabic script is picked out in gold.5 The ‘partly Egyptian, partly Assyrian’ architecture of ‘an ancient race’ that the protagonists locate suggests a composite past made up of a hodgepodge of the kinds of collections filling European and North American museums, while the revelation that the ancient people themselves have been turned to stone by catastrophic weather conditions comprising eerie white clouds and thunder and lightning, suggests that Doughty was also inspired by the destruction of Pompeii.6 The protagonists’ pursuit of a version of the Old Testament that had been written in ancient Egypt, and their journey that sees them encounter peoples described by Herodotus, is reminiscent of the ambitions of early Egyptologists: the first excavations supported by the Egypt Exploration Fund (established in 1882), for example, sought proof of the biblical exodus. The Bible and classical writings were used as guides as to what one might look for, and where.

Baroness Orczy’s short story, ‘The Revenge of Ur-Tasen’ (1900), meanwhile, is presented as a narrative rendered accessible by Egyptological processes. The tale’s subtitle – ‘Notes found written on some fragments of papyrus discovered in the caves of the Temple of Isis (the Moon) at Abydos’ – immediately indicates the story’s conceit as a product of antiquity brought to light not only through archaeological excavation (which had, in the final decades of the nineteenth century, as David Gange puts it, ‘ma[de] leaps and bounds in the direction of scientific technique’) but also through the decipherment of the ancient Egyptian language.7 Meanwhile, in Charles Dudley Lampen’s (1859–1943) Mirango the Man-Eater (1899), the opening of the narrative with the narrator purchasing a book containing ‘lengthy descriptions of the country, its features, products and inhabitants’ makes this work – upon the discovery that the civilisation is ancient Egyptian – a forerunner to the Description de l’Égypte (1809– 29). This multi-volume work on Egypt produced by Napoleon’s Bonaparte’s (1769–1821) savants is often held as the first major mile-stone in the history of Western Egyptological scholarship.8

Many of these texts, of which Lampen’s novel is a prime example, are, sadly, especially noteworthy today for their racist treatment of African and Arab people, who are used as a foil to ancient Egyptians. The similarities that these authors are keen to enforce, Egyptians being consistently presented as more akin to the Western travellers who encounter them, position modern Europeans as the rightful inheritors of ancient Egyptian culture. This ideology was evidently useful in the justification of the processes of Egyptology itself (and the removal of ancient Egyptian artefacts to museums overseas), as well as the British occupation of Egypt in 1882.

The pressure to establish a direct link between ancient Egypt and modern European culture may also go some way in explaining the emergence and perpetuation of hyperdiffusionist theories in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which posited that there was a single ancient civilisation from which all other civilisations emerged. Gange attributes to the British Egyptologist Peter le Page Renouf (1822–97) in 1878 the ‘resurrect[ion of] the enlightenment idea … that all of the world’s civilizations sprang from a single source in a glorious imperial super- civilization that had known divine knowledge but in its decadence had been destroyed by the Noachic deluge’; Renouf speculated anew ‘that ancient Egypt held memories, however vague, of a sophisticated and godly antediluvian civilization’.9 Other Egyptologists, such as Grafton Elliot Smith (1871–1937), proposed ancient Egypt as the origin point of cultural sophistication. Less widespread among Egyptologists, although popular among occultists, particularly theosophists, was the theory that Egypt had inherited its wisdom from the lost continent of Atlantis and therefore might be considered a middleman between modern civilisation and an even more ancient society. Bulwer-Lytton, whose own writings proved so influential on theosophy, believed that all religions could be traced back to ancient Egypt as their original source, which is likely why the Vril-ya of The Coming Race have architecture that suggests Egypt as well as other ancient cultures.10

The later impact of hyperdiffusionist theories on literature can be read in ‘The Green God’ (1916) by William Call Spencer (1892?–1925?), in which an obelisk carved with hieroglyphs suggests a shared heritage between the ancient Egyptians, the Chinese and the Mexicans. Fiction written for children appears particularly to draw inspiration from these theories. In Oliphant Smeaton’s A Mystery of the Pacific, a Pacific island is home to direct descendants of the ancient Romans and to a community of Black Atlanteans who live in a subterranean city. In this example, a rare exception to the rule, the Atlanteans, whose depiction is heavily Egyptianised, are imagined to be the more advanced civilisation.

A significant number of the texts considered in this article imagines ancient Egypt as having inherited its scientific learning from Atlantis, an idea that exploded in the popular cultural consciousness after the publication of the American politician Ignatius L. Donnelly’s (1831–1901) Atlantis: the antediluvian world in 1882. Donnelly’s understanding of Atlantis was derived from a fairly literal interpretation of Plato’s mythological writings on this fabled civilisation. Donnelly’s substantial volume makes several key claims in relation to Egyptian civilisation in its opening pages: first, ‘[t]hat the mythology of Egypt and Peru represented the original religion of Atlantis, which was sun-worship’; and, second, ‘[t]hat the oldest colony formed by the Atlanteans was probably in Egypt, whose civilization was a reproduction of that on the Atlantic island’.11

Donnelly’s liberal quoting of renowned authorities such as the palaeontologist Richard Owen (1804–92), and some of the most famed archaeologists and Egyptologists of the nineteenth century – Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778–1823), Jean- François Champollion (1790–1832), Karl Richard Lepsius (1810– 84) and Reginald Stuart Poole (1832–95) – imbues his text, at times, with an air of learned authority. In other instances, his reverence for Egyptian civilisation, as being the closest one might get to Atlantis in the modern age, is expressed in passionate terms: ‘Egypt was the magnificent, the golden bridge, ten thousand years long, glorious with temples and pyramids, illuminated and illustrated by the most complete and continuous records of human history’; nevertheless, he asserts, ‘even this wonderworking Nile- land is but a faint and imperfect copy’ of Atlantean civilisation.12

Donnelly’s Atlantis was widely read and made a considerable impact not just on fiction but on contemporaneous esotericism, in particular theosophy. Charles Webster Leadbeater claimed to have received Atlantean knowledge via ‘astral clairvoyance’, which in turn informed his fellow theosophist William Scott-Elliot’s (1849–1919) publication The Story of Atlantis (1896). In Scott-Elliot’s text, the author claimed that Atlanteans had such advanced technologies as airships, understanding Atlantean science and engineering to have been so sophisticated that modern civilisation was only just catching up to their achievements.

Such writings clearly informed depictions of lost worlds in which ancient Egyptians are encountered by modern individuals. As the inheritors of Atlantean knowledge, they are often depicted as magically and technologically advanced. Further, thanks to hyperdiffusionist theories, which saw occultists and Egyptologists alike seriously consider the idea that Egyptian (or an even older precursor) culture had spread across the globe, there came the possibility that archaeology would uncover evidence that such hypotheses were correct.

The idea is taken to the extreme in Jules Verne’s (1828–1905) Le Sphinx des glaces (1897), which was translated into English as An Antarctic Mystery in 1898. In French, the novel’s title and its illustrated title page depicting the monument prepare the reader for the discovery of an ‘ice sphinx’ in the Antarctic – perhaps the most surprising of Earthly locations for such a monument – while the English version, intriguingly, keeps these details concealed, perhaps in a bid to build up to a more thrilling climax. The French and English editions share an illustration by the French artist George Roux (1853–1929) of the sphinx with a skull-like face at the dénouement.13 The accompanying description emphasises the sphinx’s Grecian connotations, with Verne writing that the sphinx crouched ‘dans l’attitude du monster ailé que la mythologie grecque a placé sur la route de Thèbes’ (‘in the attitude of the winged monster that Greek mythology placed on the road to Thebes’).14 There is an Egyptian element, too, however; the original French edition of the text features a closer view of the sphinx not included in the English version, in which the sphinx’s appearance is more noticeably Egyptian, similar to that depicted on the French edition’s cover page.15 The horizontal line of its back, and the flared shape of the rock from the top of its skull evoking a nemes headdress gives it a silhouette reminiscent of the Great Sphinx of Giza.

There is no explanation as to how this sphinx materialised at the South Pole, rendering an Egyptian presence in this most inaccessible of places a mystery. Conceived as a sequel to Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) – Verne’s characters attempting to discover the fate of Poe’s eponymous protagonist – Le Sphinx des glaces concludes with a symbol of early human civilisation that cannot be deciphered. As Will Tattersdill observes, the poles in fiction of the 1890s offer up ‘not only a blank space on the map … but also an imaginative space in which science appears to be confounded’. Explorers who try to reach these points, he ascertains, ‘encounter the uncanny folded alongside the scientifically explicable, the real alongside the fantastical’.16 This is certainly the case in Verne’s fiction: an archaeological reading of the images that accompany Verne’s text tell us that this is an Egyptian sphinx, but the sphinx itself is a blank space: an unsolved riddle.

Tattersdill perceives a pattern in the scientifically informed adventure fiction of the fin de siècle that applies to narratives interested in displaced ancient Egyptian communities. Earth’s poles, he discerns, function as ‘a stepping stone to the stars, a place where spectrality and science, known and unknown, intersect with exploration and colonialism in a way which empowers a genre to leave the planet’.17 As we shall see in the coming sections, ancient Egyptians are, at times, imagined to be space travellers, and in other contexts to wield magical powers that allow them to travel through time, no longer occupying the blank spaces on the map, but having escaped the map itself. If the poles offered up a blank canvas for the imagination of a scientifically informed fantastic, then so too might Earth’s nearest neighbours: Venus and Mars. It is to the night sky, as another potential site of Egyptian knowledge and, therefore, Egyptian presences, to which we now cast our gaze.

Astronomy

As with archaeology, astronomy – once an elite pursuit – became increasingly accessible to the middle classes across the nineteenth century. With revolutions in printing, images depicting astronomy or astronomical phenomena also became more available. Among these were imaginative renderings of ancient astronomers.

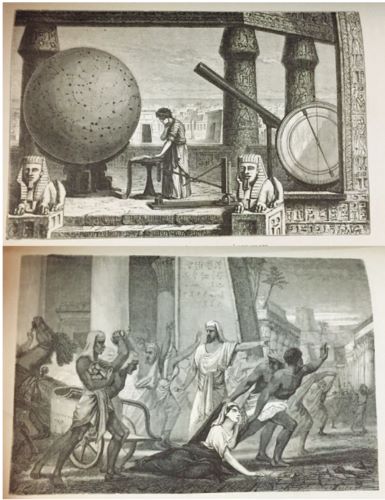

The instalment of French scientist and writer Louis Figuier’s (1819–94) five-volume Vies des Savants illustres (1866–70), devoted to ‘Savants de l’antiquité’, features numerous engravings of the great ‘scientists of antiquity’ set against meticulously rendered ancient Egyptian architecture. Such images depict ‘Pythagore chez les prêtres Égyptiens’ (‘Pythagoras among the Egyptian priests’) in an imposing temple space; ‘Euclide présente a Ptolémée Soter ses Éléments de Géographie’ (‘Euclid presenting to Ptolemy Soter his Elements of Geography’) presumably in Ptolemy’s palace; ‘Apollonius dans le Musée d’Alexandrie’ (‘Apollonius in the Alexandria Museum’), again in a building dominated by fine architectural detail; and Ptolémée Soter fait construire le muséum d’Alexandrie’ (‘Ptolemy Soter building the Alexandria Museum’).18 In all of the aforementioned images, Figuier’s work emphasises the Egyptian setting as one associated with the giants of ancient philosophy and science, and, elsewhere in this volume, a particular visual connection emerges between ancient Egyptian architecture and astronomy.

‘Hipparque à l’observatoire d’Alexandrie’ (‘Hipparchus at the Alexandria observatory’), for example, depicts the eponymous astronomer surrounded by sizeable astronomical equipment and looking up into a starry sky over the city, recognisably Egyptian thanks to its pylon- shaped architecture along with a conspicuous obelisk.19 A later image, ‘Claude Ptolémée dans l’observatoire d’Alexandrie’ (‘Claudius Ptolemy in the Alexandria Observatory’) returns to this setting, albeit an alternative view, in which twin sphinxes flank the savant (figure 2.1).20 Claudius Ptolemy (c.100– 170 CE) studies a scroll before an enormous globe depicting the constellations, held aloft by seated ancient Egyptian figures that are, like the sphinxes, denoted as divine through their stylised beards. Such symbolism in these images reinforces an understanding of ancient Egyptian deities as guardians of knowledge.

The volume’s final illustration, entitled ‘Mort de la philosophe Hypatie, à Alexandrie’ (‘Death of the philosopher Hypatia in Alexandria’), depicts a more frantic scene in front of rather than inside this impressive Egyptian architecture, as the philosopher and astronomer Hypatia (c.370–415 CE) is torn from her carriage (the carriage’s high level of detail suggesting the consultation of genuine ancient Egyptian sources by the unnamed artist), moments before being beaten to death (figure 2.1).21 While the image does not picture Hypatia with her scientific apparatus or in quiet contemplation as with the other astronomers, her learning is suggested by the image’s composition: a tall pylon shape in the background divides the image vertically in two, with Hypatia herself occupying the central position at the bottom of the scene. With the pylon looming above her, inscribed with hieroglyphs, Hypatia is aligned with the hieroglyphic script as emblematic of mystical learning, and is thus marked out as the inheritor of – and contributor to – the lore of the ancients.

Around the same time as Figuier’s Vies des Savants illustres, astronomical observation was becoming more widely practised in Egypt itself. The Khedivial Astronomical Observatory was founded in Cairo in 1868 and, just under half a century later, moved to a new site with better visual conditions at Helwan, built between 1903 and 1904. It was here, in 1909 and 1911, that photographic records of Halley’s comet were first produced. The popular press also furthered an association between Egypt and astronomical phenomena, reproducing picturesque scenes of shooting stars streaking over Egyptian landscapes. In one example, from an 1882 issue of The Graphic, entitled ‘The comet as seen from the pyramids from a sketch by a military officer’ (figure 2.2), the comet leaves an impressive trail of light behind it, reflected in the waters of the Nile. As the accompanying article relayed, ‘the comet is seen in Egypt in all its magnificence, and the sight in the early morning from the Pyramids (our sketch was taken at 4 A.M.) is described as unusually grand’.22 Earlier that year, one of the brightest comets on record was witnessed in Egypt; named Tewfik, after Mohamed Tewfik Pasha (1853–92), then Khedive of Egypt, the comet was seen – and photographed – during a solar eclipse that had brought a host of British astronomers to Egypt, cementing Egypt’s reputation as an excellent location for modern astronomical enquiry.

The coming together of interests in astronomy and ancient Egyptian civilisation is of particular import to an understanding of the science fiction that emerged as the twentieth century approached. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, key individuals who were interested in astronomy – specifically in the planet Mars – were also occupied in archaeological study of ancient Egyptian sites; combining these two interests created the subdiscipline of archeoastronomy. Out of this context, and building on the ancient Egyptians’ reputation as the stargazers who had imparted their knowledge to the Greek astronomers, emerges some of the earliest science-fiction works to imagine ancient Egyptians as space travellers. Fred T. Jane and Garrett P. Serviss – authors who have thus far attracted little attention from literary scholars – both wrote novels that sprang from this context, producing narratives in which ancient Egypt is not merely emblematic of the past but also of future civilisations and technologies. These speculative fictions can be seen to have been born of the space devoted in popular scientific works to imaginative speculations about the fate of the Egyptian monuments thousands of years into the future.

An intermingling of astronomical expertise and an interest in the Great Pyramid is best typified in the late nineteenth century by the British astronomer Richard Proctor.23 Best known for his maps of Mars, Proctor understood the planet’s dark patches to be oceans, and lighter patches to be land masses. This work built on images and observations by earlier astronomers, but Proctor’s work would prove enormously impactful in designating some of these areas and in the diagrammatic act of mapping. In the 1880s he also published on subjects including the Great Pyramid as astronomical observatory, again using technical drawings, and details of precise measurements to support his hypothesis. Despite these features, Proctor’s main ambition was to appeal to a popular rather than an exclusively scientific, scholarly audience, evident in the adornment of his work with images to capture the imagination. These illustrations included a rendering of what ancient Egyptian astronomers might have seen of the night sky from the Great Pyramid, which appeared in several astronomical publications from 1891 until at least 1912 (figure 2.3), designed by the French illustrator Louis Poyet, whose work appeared in an array of popularising scientific venues in the late nineteenth century.24

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835–1910) built upon Proctor’s mapping of Mars, his own diagrams going into more surface detail than Proctor’s. Between the 1870s and 1880s an interesting change is detectable in Schiaparelli’s images, in which some of the dark lines he could see on the surface of the planet were represented in much straighter, more regular ways. Continuing Proctor’s work, Schiaparelli named these lines after rivers on Earth and mythological figures. These included the names of Egyptian gods: Anubis, Apis, Athyr (Hathor), Isis and Thoth. There was even a Martian Nile: Nilus.

Egyptian appellations entered into astronomy in the nineteenth century. Egyptian names had been given to asteroids from the 1850s, though the first of these, the naming of the asteroid Isis by the British astronomer Norman Robert Pogson (1829–91), was actually in honour of his daughter, Elizabeth Isis Pogson (1852–1945). Isis, as she was known, was an astronomer in her own right, who would go on to be the first woman nominated to be elected a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society.25 Subsequently, a meteor discovered by the Canadian-American astronomer James Craig Watson (1838–80) in 1876 was named Athor after the Egyptian goddess of motherhood, love, sexuality, music and dance. The German-American astronomer Christian Heinrich Friedrich Peters (1813–90) named a meteor that he discovered in 1889 Nephthys after the Egyptian goddess associated with mourning, protection and the night (Nephthys was the final meteor of the 47 discovered by Peters, who was at this stage likely running out of his preferred Classical names). In 1917, the German astronomer Max Wolf (1863–1932) dis-covered an asteroid which he named Aïda after the opera of the same name by Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901), a work set in ancient Egypt, and the following year he named another asteroid Sphinx, likely an allusion to Greek mythology rather than Egyptian, but nonetheless with ancient Egyptian connotations.

Naming – and the misinterpretation of such labels – is crucial to what transpired next in scholarly work on Mars, and its representation in popular culture. It was Schiaparelli’s terming of these lines as ‘canali’ – the Italian word for ‘channels’ – which famously led to the mistranslation of these patterns as ‘canals’ by the American astronomer Percival Lowell (1855–1916). This error implied that there was some kind of agency behind the creation of these features, rather than them simply being natural features on the planet’s surface.26 For these structures to have been artificially created, there had to be intelligent life on Mars.

While Lowell was by no means the first astronomer to suggest the prospect of civilised life on Mars, his understanding of these dark lines as canals (or other artificial structures) is enormously significant in its impact on the science and science fiction of the 1890s and beyond. Lowell’s drawings of Mars suggest even more geometric, regular shapes than Schiaparelli’s, and picture a planet covered – supposedly – in a complex web of waterways far more sophisticated than had been achieved on Earth.27 The completion of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the attempts to construct the Panama canal across the 1880s and 1890s (which would not be successful until the early twentieth century), were proving – and would prove – world-changing in terms of international trade.28 The imperialistic fanfare with which the opening of the French- controlled Suez Canal was celebrated on the cusp of the 1870s – in tandem with Lowell’s work and others – may well have encouraged parallels in the minds of those who were interested in the supposedly superior efforts of Martian engineers; such subjects certainly dominated scholarly and popular discussion about the planet in the 1890s. It was perhaps only a small leap to see the pinnacle of canal engineering in Suez as if it were replicated – and superseded – in the 288 canals Lowell claimed to have documented on the surface of Mars.

Lowell was also fascinated by another considerable feat of human engineering: the Great Pyramid. Indeed, in 1912, heavily influenced by Proctor’s work, he declared the Great Pyramid ‘the most superb [observatory] ever erected’, specifying that ‘it had for telescopes something whose size has not yet been exceeded’.29 While Lowell by no means asserts the overall superiority of the ancient Egyptian astronomers or their equipment over their modern counterparts, he does underline the unsurpassed scale of ancient Egyptian monumental construction. Lowell identifies one way, at least, in which ancient Egyptian achievements had not yet been overtaken by modern civilisation, an idea which had already proven influential in science fiction, by this time, for at least a couple of decades.

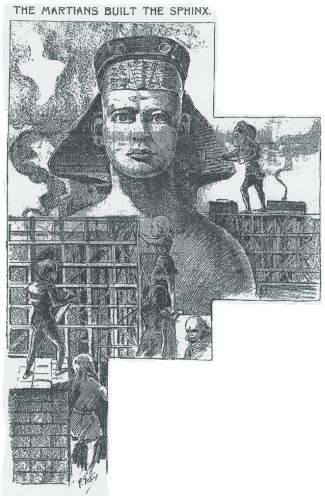

As if drawn directly from the debates of the 1890s, the naming of Martian features after Egyptian deities, and the parallels emerging between the Suez Canal and Martian structures, Garrett P. Serviss’s 1898 novel Edison’s Conquest of Mars features a textual and visual representation of the Great Sphinx of Giza as originally constructed by Martians rather than Egyptians, depicted in an image by an illustrator by the name of P. Gray (figure 2.4). Serviss himself was an astronomer, though his eclectic career also encompassed a period working for The New York Sun from 1876 to 1892. A sense of popular, journalistic writing is evident in his popular scientific works, as well as in his fictional output, which comprises five novels and a short story. Edison’s Conquest of Mars was Serviss’s first foray into fiction, commissioned by The Boston Post as a sequel to an unauthorised and heavily edited version of H. G. Wells’s 1897 novel The War of the Worlds, entitled Fighters from Mars or the War of the Worlds, which had been serialised in The New York Evening Journal.

In Serviss’s text, a group of men are selected to venture to Mars by the American inventor Thomas Edison. Their aim is to destroy the Martians, who had previously made such a devastating attack on Earth, and they travel into space and to Mars itself to remove any future threat. That Mars is going to transpire to be connected to ancient Egypt in some way is foreshadowed in Edison’s selection process. As Serviss’s narrator relates, ‘[o] n the model of the celebrated corps of literary and scientific men which Napoleon carried with him in his invasion of Egypt, Mr. Edison selected a company of the foremost’ scientists from a wealth of disciplines – ‘astronomers, archaeologists, anthropologists, botanists, bacteriologists, chemists, physicists, mathematicians, mechanicians, meteorologists and experts in mining’ – ‘as well as artists and photographers’.30 The flooding of Mars at the novel’s conclusion means that these experts have little opportunity ‘to gather materials in comparison with which the discoveries made among the ruins of ancient empires in Egypt and Babylonia’, though it is clear in Serviss’s comparison to Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt 100 years before the publication of his novel that this is a mission of cultural imperialism as much as martial domination.

It transpires that there is indeed a historical connection between Mars and Egypt. A beautiful woman called Aina, whose ancestors hail from a utopian civilisation in Kashmir, tells the story of an ancient Martian invasion of Earth, which led to the construction of the pyramids and Sphinx. The Martians ‘suddenly dropped down out of the sky … and began to slay and burn and make desolate’.31 ‘Some of the wise men’, she relates, ‘said that this thing had come upon our people because … the gods in Heaven were angry’, this reference being the first of several that understands the arrival of the Martians in terms of the plagues in Egypt outlined in the Old Testament. Indeed, what follows is a blend of biblical narrative and pseudoarchaeology:

they carried off from … our native land … a large number of our people, taking them first into a strange country, where there were oceans of sand, but where a great river … created a narrow land of fertility. Here, after having slain and driven out the native inhabitants, they remained for many years, keeping our people, whom they had carried into captivity, as slaves … And in this Land … it is said, they did many wonderful works.32

Aina’s language and syntax even shifts into a kind of biblical archaism as she recounts this story. While her people are from Kashmir rather than Atlantis, they function very much as Atlanteans do in the understandings of the origins of ancient Egyptian civilisation proposed by Donnelly and his adherents. Uprooted from their original home, the former inhabitants of this utopian civilisation are taken to Egypt, where the Martians assume the role of the ruling class, while they themselves – like the Israelites in the Bible – are enslaved. Aina communicates that the Martians, who had been so impressed with the mountains in Kashmir, erected ‘with huge blocks of stone mountains in imitation of what they had seen’, the blocks ‘swung into their lofty elevation’ not by ‘puny man, as many an engineer had declared that it could not be, but … these giants of Mars’.33 In keeping with biblical understandings of Egypt as emblematic of despotism and absolute power, the Sphinx is revealed to be ‘a gigantic image of the great chief who led them in their conquest of our world’.34 What follows is an allusion to Wells’s The War of the Worlds, which concludes with the invading Martians overcome by pathogens, couched in biblical terms; it is only when ‘a great pestilence broke out’, interpreted as the ‘scourge of the gods’, that the Martians ‘returned to their own world’, taking with them the Kashmiri people.

The Great Sphinx was evidently of symbolic interest to Serviss. He would return to this monument in his story of a great flood (on Earth, rather than on Mars), The Second Deluge, serialised in The Cavalier in 1911 and then published in single- volume novel format in 1912 with illustrations by George Varian (1865-1923). Travelling the flooded world in a submarine named the Jules Verne, in a nod to his novel’s inheritance from the French author, Serviss’s protagonists accidentally collide with the Sphinx, causing a surface layer of the monument to fall away. This leaves ‘an enormous black figure, seated on a kind of throne, and staring into their faces with flaming eyes’ emitting ‘flashes of fire’.35 In the futuristic image of the sphinx provided by Varian, not only do we see light-emitting eyes that suggest advanced technology and also of a kind of occult potency, but the hieroglyphic symbols that adorn the sphinx evoke scientific diagrams. As we read on, we discover that this is a symbolic ‘representation of a world overwhelmed with a deluge’, under which is inscribed a hieroglyphic message reading ‘I Come Again – | At the End of Time’.36 The Great Sphinx is revealed to have been – all along – a record of a prophecy that a second flood would overwhelm the Earth.

While the direct influence of one on the other cannot be determined, it is striking that this scenario is suggested in Richard Proctor’s article ‘The Pyramid of Cheops’, which appeared in The North American Review in March 1883. Proctor states that:

Compared with the vast periods of time thus brought before our thoughts as among the demonstrated yet inconceivable truths of science, the life-time of such a structure as the great pyramid seems but as the duration of a breath. Yet, viewed as men must view the works of man, the pyramids of Egypt derive a profound interest from their antiquity. Young, compared with the works of nature, they are, of all men’s works, the most ancient. They were ancient when temples and abbeys whose ruins now alone remain, were erected, and it seems as though they would endure till long after the last traces of any building now existing, or likely to be built by modern men, has disappeared from the surface of the earth. Nothing, it should seem, but some vast natural catastrophe ingulfing them beneath a new ocean … can destroy them utterly, unless the same race of beings which undertook to rear these vast masses should take in hand the task of destroying them.37

Returning to Proctor here is useful in showing how astronomers and scientific popularisers were themselves devoting part of their non- fiction texts to the kinds of speculation that we are more familiar with in genre fiction – imagining in this passage, in Proctor’s case, a scenario similar to Serviss’s, in which Egyptian monuments are subsumed beneath flood waters. Moreover, it offers up for examination intriguing linguistic nuances. Proctor credits the ancient Egyptians alone as having the power to remove their structures, referring to them as a ‘race of beings’. In Proctor’s use of the term ‘beings’ we are invited to imagine the ancient Egyptians as something other than human, chiming with depictions of them in science fiction. Even if in some of these fictions the Egyptians are still human, they are imagined as living an extraterrestrial existence.

The other work of science fiction of especial interest to us deals not with Mars but with Venus, though the planets are essentially interchangeable. Both written and illustrated by Fred T. Jane, his novel To Venus in Five Seconds imagines pyramids as landing and take-off sites for vehicles that move so fast that the movement is almost akin to teleportation, and ancient Egyptians (originally hailing from Mexico, suggesting Donnelly’s theories) as effectively migrating to form a community of humans on Venus. There, they live alongside the indigenous intelligent species called the Thotheen, presumably named after Thoth, the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom. The Egyptians are inferior to the Thotheen in all sciences except medicine, and so they are permitted to remain on the planet in their capacity as superior physicians.

Jane’s protagonist, a medical student called Plummer, encounters a fellow student named Zumeena, who seems to be romantically interested in him. While socialising, Zumeena takes Plummer into what appears to be a summer house, but that, once Plummer is inside, is evidently some kind of contraption. This is no ordinary structure, and within five seconds of the door having been closed Plummer is transported to Venus, an experience that he, at first, believes to be an illusion exceeding the feats of ‘Maskelyne and Cooke’.38 It is while there that Zumeena – as Aina does in Serviss’s novel – provides the historical background detailing how ancient Egyptians came to be on another planet:

The origins of the pyramids, which a later and more utilitarian age made into tombs, was really nothing more nor less than a convenient form for the system of transit we perfected some eight thousand years ago. You will find identical pyramids in Mexico and Egypt, and between these two points we carried on continual intercourse by means of argon- coated cars. By pure chance and accident a party of my ancestors, being in one of these cars upon a sandy plain, were suddenly transferred to this planet.39

The similarity between the pyramids of Mexico and Egypt reveals Donnelly as an influence on Jane’s ideas, while the reference to argon, which had been first isolated from air just a few years before in 1894, underlines how the most up-to-date chemical knowledge was very much integrated into Egyptian technologies 8,000 years prior.

While such details serve to underscore the ancient Egyptians’ vastly superior scientific advancement, ultimately, the superiority of the Thotheen and the humans on Venus is called into question in one regard: while they are more scientifically and technologically developed, they subscribe to problematic ethical systems. Once Plummer rejects Zumeena’s advances, she resolves to vivisect him, along with the other earthlings that her people have abducted (the threat of the Thotheen and ancient Egyptians depicted in figure 2.5). Taking their captives through a utilitarian building whose pylon- shaped doors are a decorative nod to Egypt, the ancient Egyptians – now turned antagonists – ruthlessly pursue medical advancement at the expense of human life.

This was not the only occasion upon which Jane used ancient Egyptian imagery to represent technological modernity. While best remembered as an expert on warships and aircraft, and as a wargamer, Jane was also a talented illustrator, who provided artwork for the science-fiction novels of George Griffith among others. He also produced a series of speculative images of the future commissioned by The Pall Mall Magazine in 1895, which included one design showing ‘a dinner party AD 2000’ in which servers dressed in ancient Egyptian costume distribute ‘chemical foods’ inside a building clearly inspired by an Egyptian temple.40 This world appears at once ancient and futuristic, with the view outside showing the top of an obelisk, as well as hovering balloons projecting light downwards to illuminate the city below. The image also offers up a fascinating contrast between the people present. Jane pictures white Europeans being served by waiters in ancient Egyptian-inspired costume. There is clearly a hierarchy here, in which ancient Egypt is subservient, its feats of engineering appropriated for the modern world, along with, perhaps, its alchemical knowledge, which may be the basis of the ‘chemical foods’ consumed by the elite.

As Nathaniel Robert Walker observes, ‘Jane placed a poetic signature that may contain a hint for decoding his Oriental futurism’ amidst this image.41 ‘On the lintel is an inscription reading “Janus Edificator”, below a winged, double-faced head’, Walker notes, reading this as both an allusion to Jane himself, and ‘also the Classical double-faced god of doorways, windows, and, appropriately, of time’. He reads in this image ‘a unifying, evolutionary synthesis of all time and space’.42 Walker is correct in his assertion, citing Edward Said, that ‘the East’ is often imagined in Western culture as ‘an irrational, decrepit “Other” ’, and that at times ‘the merging of Oriental and Occidental architecture was gleefully presented as an imperial appropriation of the former by the latter’, such ‘hybrid architectures … calculated to express the tantalizing possibilities inherent in a world that was shrinking due to the proliferation of space- and time-annihilating technologies’.43 I believe that there is something more nuanced in this illustration, however; certainly, ancient Egypt is imagined as subservient to the Westerners of the future, but this is not because they are the ‘irrational, decrepit’ denizens of the East. Rather, the subservience of a civilisation often held aloft in contemporaneous culture as sophisticated casts the image’s Europeans as even more so.

Reading this image in the context of Jane’s other work is also illuminating, establishing a kind of progression in his conception of ancient Egyptian cultural sophistication over time. By the time Jane wrote and illustrated his own narrative in To Venus in Five Seconds, published two years after this image, Egypt is no longer imagined as subservient to Western culture, but is a very real threat, embodying the ‘vengeance theme’ that Ailise Bulfin has identified in a body of Egyptian-themed fiction emerging in the 1860s and swelling at the fin de siècle.44 Ancient Egyptians in Jane’s text are very much the dominant people in terms of power and scientific advancement, and Plummer is lucky to escape with his life. The very opposite of service is depicted in Jane’s own image of ancient Egyptians physically dominating the Westerners whom they have abducted.

Despite their differences, both Serviss’s and Jane’s texts relocate Egyptian presences to other planets, revealing that ancient Egyptian civilisation is not confined to earthly ruins, but lives on elsewhere. Both texts are noteworthy, too, for their imagination of Egyptian monuments as markers of extraterrestrial cultures, in the Martian origins of the Great Sphinx in Serviss’s case, or, in Jane’s, the pyramids reconfigured as transport devices between Earth and Venus. These sites, of archaeological and astronomical interest across the nineteenth century, cannot be comprehended by the practitioners of these disciplines, however, resisting conventional understanding. Instead, they highlight the work to be done in filling in the blanks left by advanced peoples, if not blank spaces yet to be filled in imperialist atlases, then in the scholarly tomes of archaeologists and astronomers.

Time Travel

Time-travel stories as devised by various science- fiction pioneers in the nineteenth century were especially interested in accessing ancient Egypt and its future legacies. Mid-century narratives often used sleep as a device to conceptualise more rapid passing of time than the typical waking human experiences, exaggerated to the extreme (a literary device that stretches back to antiquity). The German Egyptologist Max Uhlemann’s (d.1862) Drei Tage in Memphis (1856) and the British children’s author Henry Cadwallader Adams’s (1817–99) Sivan the Sleeper: a tale of all time (1857), both use sleep as a process whereby other eras are accessed. The former is an extended dream-like journey to the past, facilitated by the spirit of the deity Horus (a scrap of papyrus on which is written a hieroglyphic message being the ‘proof’ that it was no mere dream); the latter sees the eponymous ancient Egyptian protagonist use periods of sleep to make significant temporal jumps.45

Subsequent to these examples, ancient Egypt proved integral to several of the most innovative and influential time travel narratives in the decades that followed. The American minister and historian Edward Everett Hale’s (1822–1909) ‘Hands Off’ (1881) – a short story first published anonymously in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine – is a cosmic alternate history. While not, as Karen Hellekson asserts, ‘the first example known to date of a work that deals with the time-travel paradox: a backward- traveling time traveler who causes the events [they] went back to study’, ‘Hands Off’ does illustrate (well in advance of chaos theory) the concept of the ‘butterfly effect’, whereby one small change to events in the past is shown to have major consequences.46 In ‘Hands Off’, with little in the way of explanation as to how they arrive in this state, Hale’s narrator opens the story by describing being ‘free from the limits of Time and in new relations to Space’, privy to thousands of solar systems.47 The narrator chooses to witness Joseph’s journey towards Egypt, ultimately to be sold into slavery, as in the Bible’s Book of Genesis. It transpires that there are other Earths amidst these duplicate solar systems, though, and the narrator witnesses a different version of the world, in which they themselves interfere. Killing a guard dog, the narrator allows Joseph to escape and to return to his father, Jacob. This action has significant repercussions: as Joseph never goes to Egypt, and never predicts years of plenty followed by years of famine, the Egyptian granaries are drained of their store. As a result, Egypt falls. Greek civilisation does not develop without Egyptian knowledge; in the end, there is ‘[n]o Israel … no Egypt, no Iran, no Greece, no Rome’, and the human race rapidly dies out.48 There are no lasting ramifications, thankfully, this being a world of ‘phantoms’ – a duplicate of our world rather than the genuine article – and the narrator learns, ultimately, not to interfere. Hale’s work is noteworthy (beyond its historical significance as, perhaps, the first example of the butterfly effect in fiction) for its imagination of multiple worlds, long predating the serious scientific consideration of this concept. As Paul J. Nahin asserts, the ‘idea of a multitude of worlds … (of which ours is but one) sounds very much like the many-worlds view of reality that many find implicit in theoretical quantum mechanics’.49 Nahin dates the first earnest proposal of this idea in science to 1957, three- quarters of a century after Hale’s short story, and over a century after the idea’s first depiction in art in the French artist Jean-Ignace Isidore Gérard’s (1803–47) Un Autre Monde (1844).

Egypt also contributes to other milestones in the history of time-travel fiction, performing a crucial role in Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet. This novel is, according to Somi Ahn, ‘the first time-travel narrative written for children’.50 This makes the children’s first journey through space and time to predynastic Egypt the original spatiotemporal moment accessed by time travellers in children’s literature. Indeed, it is not just the child protagonists who travel through time, but also the Egyptian priest Rekh-marā who, like the children, harnesses the amulet’s ‘power to move to and fro in time as well as in space’, meaning that an ancient Egyptian is the first independent time- travelling adult in children’s fiction.51

Tales of time travel often function similarly to the lost- world genre, though instead of the text’s protagonists being geographically displaced they are temporally so, usually (though not always) encountering Egyptian antiquity in Egypt itself rather than in an imagined alternative location. While archaeology and its relics likely offered up inspiration for lost- world narratives given how many of these texts begin with frame narrative based around a particular artefact, immersive simulacra of ancient Egypt in its glorious heyday that proliferated in metropolitan spaces – entertainment and education venues – suggested experiences of time travel.

The presence of ancient Egypt in London and other major cities was increasingly felt across the nineteenth century, as museums acquired and displayed Egyptian artefacts for their visitors, theatrical productions drew upon ancient Egypt’s glamour, and metropolitan architecture incorporated ancient Egyptian elements. These fantastical pockets of ancient Egypt in the modern world crop up throughout, though one example of particular importance for our purposes here is the Egyptian Court at the Crystal Palace, a space that, for thousands of British people from the nineteenth century onwards, as Stephanie Moser records, provided ‘their first visual encounter with ancient Egypt’.52 The Egyptian Court was a new feature when the Crystal Palace, once occupying Hyde Park, was reassembled at Sydenham in 1854. The grandest rendering of ancient Egypt from the mid-nineteenth century until the destruction of the Crystal Palace by a fire in 1936, the Egyptian Court was unusual in that its statues were painted in dazzling polychrome, a level of detail conferring unprecedented authenticity (in Britain, at least) to this spectacle. Many of the finer details were based upon the notes and sketches of the Court’s creators – the architect Owen Jones (1809–74) and the sculptor and artist Joseph Bonomi Jr (1796–1878) – made during independent excursions in Egypt, along with casts of relics in Europe’s major museums. Despite this, the Egyptian Court did not resemble the ruins of ancient Egypt, but rather the great civilisation as it might be imagined at its cultural peak. The experience may well have suggested time travel (albeit to a composite ancient Egypt rather than any one distinct moment in ancient Egyptian history), and indeed, in The Story of the Amulet, one of the child protagonists, Anthea, expresses an interest in going back in time to ancient Egypt ‘to see Pharaoh’s house’ as she ‘wonder[s] whether it’s like the Egyptian Court in the Crystal Palace’.53

The Egyptian Court was one of several zones at the Crystal Palace meant to reconstruct the art and architecture of various times and places: there was a court to represent Medieval Europe, and another for Renaissance Europe, along with the Alhambra, ancient Rome, ancient Greece and Pompeii. Experiences of far older times were complicated by the introduction of modern technologies into these spaces. A journalist writing for The Illustrated London News in 1892, for instance, commented on how ‘[i]n the Egyptian Court we can hear instrumental music and comic opera wafted … from London, Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool’.54 Just as sound technologies meant that recordings from various places could be played in settings far removed, and audio captured in the past could be replayed at a later time, so too did spaces like the Crystal Palace, in its very organisation, and in the introduction of such technologies into these interconnected zones, suggest the breakdown of conventional understandings of time and space. Indeed, the quick (and, indeed, non-linear) movement one might make between the various courts by visitors to the Crystal Palace might have offered itself up as an interactive predecessor to time-travel narratives that imagine their protagonists moving swiftly between several different societies of historical interest, as Nesbit’s novel does.

That the Crystal Palace and the British Museum were favourite destinations of Nesbit in her own childhood implies the strong impact that these real spaces had on her conception of enchantment in her children’s fiction.55 The children in The Story of the Amulet only refer to the Egyptian Court by name, never actually venturing to the Crystal Palace in this novel, though they do visit the British Museum several times. As Joanna Paul notes of this text, ‘the British Museum … becom[es] the portal through which the children enter the future utopian London’.56 While the titular amulet is how time travel is accomplished in Nesbit’s novel, the British Museum itself also allows access to disparate times and places. Michel Foucault’s (1926–84) understanding of the museum as the ultimate ‘heterotopia of time’ is a useful way of comprehending why museums suggest themselves as intriguing settings for such fiction. For Foucault as, apparently, for Nesbit, ‘[m]useums … are heterotopias in which time never ceases to pile up’, which hinge on ‘the idea of accumulating everything … the desire to contain all times, all ages, all forms, all tastes in one place, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside time and protected from its erosion’.57 While The Story of the Amulet certainly casts the British Museum in such a light, this is by no means common to all time-travel narratives. The Palace of Green Porcelain in H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine is recognisable as having been a museum akin to those of the Time Traveller’s own era in its amassing of artefacts from the furthest reaches of the globe. The museum is, however, shown to succumb to the ravages of time, itself falling to ruin. Wells imagines a world in which even the museum has itself become a kind of archaeological site, with its ‘inscription[s] in some unknown character’ and its ‘floor … thick with dust’.58 While Wells’s Time Traveller does not venture to Egypt in any period of its history, that this future London with its ruined museum is watched over by a subtly smiling sculpture of a sphinx is a powerful allusion to ancient Egyptian iconography. It is to Wells’s The Time Machine, and its relationship to The Story of the Amulet, that we now turn. In both texts, the line between London and Egypt, the past, present and future, is rendered indistinct, suggesting the temporal collapse encouraged by the cityscape itself.

The cultural pervasiveness of ancient Egypt in the city setting is exemplified in The Time Machine, in which Wells imagines the London suburbs in the year 802,701. The first landmark that the Time Traveller sees in this future moment is a statue of a sphinx, ‘[a] colossal figure, carved apparently in some white stone’, while ‘all else of the world was invisible’.59 Made from marble, replete with spread wings and somewhat weatherworn, the sphinx is a guardian of sorts to the changed world in which the Time Traveller finds himself. The sphinx does not appear to the Time Traveller to be masculine or feminine and, as such, is referred to throughout by the neutral pronoun ‘it’, though the Time Traveller’s repeated references to the sphinx’s smile imbues the statue with an almost enchanted sentience. A hailstorm veils much of the Time Traveller’s surroundings from his sight, and the hail falling harder and softer gives the ‘winged sphinx’ the appearance of ‘advanc[ing] and reced[ing]’ within this gloomy landscape, much like the visual effects of the phantasmagoria.60 If we subscribe to David Shackleton’s reading of the Time Traveller’s view of the ‘dreamlike and insubstantial’ shifting landscape as he travels a mirroring of ‘the magic lantern displays and phantasmagoria that geological lecturers used as visual aids’ in their ‘geological time travel’ displays ‘from the 1830s onwards’, so too does the Time Traveller’s encounter with the sphinx suggest the archaeological subject matter employed in magic lantern shows.61

Just like the Time Traveller, the original readers of Wells’s narrative as it was first published in the United Kingdom in novel format by William Heinemann in 1895 would, before opening the novella’s first page, have been confronted by the sphinx.62 Embossed in dark ink on the first UK edition’s sandy- coloured covers (figure 2.6) – according to Leon Stover ‘[a]t the author’s insistence’63 – is a simplistic line drawing of a sphinx couchant, informed by ancient Egyptian iconography. This sphinx, a design commonly attributed to one Ben Hardy, wears the distinctive nemes headdress of the pharaohs. Even in this hyper- futuristic setting, the Egyptianised elements infiltrating the London landscape are imagined not only to have continued to spring up, but to have survived. Embodying both the ancient past and the distant future, the sphinx symbolises (among other things) both the timelessness of the Egyptian fantastic and the metropolis’s capacity to act as a gateway to the exotic.

Critics who recognise the sphinx’s centrality or symbolic significance in Wells’s imagined future have nonetheless often overlooked its Egyptianness, with Terry W. Thompson and Peter Firchow even declaring it (independently of one another) Greek rather than Egyptian.64 Admittedly, any Egyptian qualities are not made verbally explicit, though Wells apparently requested that the sphinx appear on the cover of the Heinemann edition; one would hope that the sphinx as it appeared would have been drawn up to the author’s specifications.

The judgements of earlier scholars have not stopped others, among them Margaret Ann Debelius, from recognising the cultural hybridity of Wells’s sphinx, and Egypt’s role in this hybridity, however. As Debelius asserts, alluding to Egypt and Greece respectively, the sphinx is ‘a curious amalgam of eastern and western tradition’.65 I would add that if the nemes headdress specifically codes Wells’s sphinx as Egyptian, the wings mark it out as Greek or Assyrian (or both). In fact, Assyrian sphinxes – far more often than their Greek counterparts – are depicted with wings held aloft, rather than at their sides. My point is that while Wells’s sphinx is not exclusively Egyptian, it does, in concrete ways, evoke something explicitly Egyptian in its design.

The component parts of Wells’s sphinx as it appears on the Heinemann cover resemble pre- existing hybrid imagery that could be seen, for instance, in Wedgwood products. Sphinx ornaments produced by the pottery company from the late eighteenth century to at least around the 1880s feature these creatures in much the same pose, with nemes headdress and wings. Wedgwood wares often combined imagery from different ancient civilisations (pieces that were supposed to look Egyptian often featured Greek sphinxes, crouching female creatures who have adopted a nemes for the occasion), so the kind of iconographic hybridity that we see in the Heinemann motif echoes iconography that was then in circulation, not just in the elite products produced by Wedgwood but in cheaper alternatives targeting a less affluent consumer.66 Such Wedgwood pieces are themselves reminiscent of genuine ancient Egyptian examples (aside from the wings), and were perhaps originally inspired by French Egyptian Revival designs, which also saw the introduction of wings onto otherwise fairly faithful reproductions. Regardless of the source for this particular image, however, the sphinx’s cultural hybridity indicates that the future of Wells’s Time Traveller bears a particular resemblance to the ancient past. This ancient past combines several features to suggest a kind of composite Orientalised decadence, rather than simply reverting to one specific ancient culture.

While the first American edition published by Henry Holt (which predated the Heinemann edition in the United Kingdom by a matter of weeks) does not feature a specific design on the cover (the front’s sole decoration being the publisher’s emblem), it does include a frontispiece depicting the sphinx, created by illustrator W. B. Russell.67 While Russell’s sphinx wears a shorter headdress than that of the sphinx adorning the Heinemann cover, this nonetheless gives it an appearance more reminiscent of the Sphinx of Giza, the most famous Egyptian sphinx of all.

In fact, Debelius argues convincingly that Wells’s original readership would have ‘specifically’ read the white sphinx in the context of ‘Britain’s military occupation of Egypt’ and ‘the Great Sphinx of Giza’; perhaps Russell was influenced by this context, too, in his visual representation of Wells’s sphinx.68 Indeed, Debelius claims that ‘Wells’ split society sounds even more like Cairo under British occupation’ than it does the author’s contemporary Britain.69 Supporting Debelius’s reading is the Time Traveller’s repeated Orientalisation of the landscape; he observes that the archway into the ‘colossal’ building in which the Eloi sleep is ‘suggesti[ve] of old Phœnician decorations’, while at the crest of a hill he finds a seat with ‘arm-rests cast and filed into the resemblance of griffins’ heads’, the earliest examples of the image of the griffin dating back to ancient Egypt and ancient Iran.70 Looking over the vista, he observes ‘here and there … the sharp vertical line of some cupola’ (evocative of minarets) ‘or obelisk’, features that encourage parallels that might be made between Cairo and the London suburbs of the future.71 Aside from the industrial technologies of the Morlocks, this is an age where most of the trappings of the Time Traveller’s civilisation – including knowledge of a written language – have slipped away, and so his encounter with this new world in which he finds himself unable to decipher traces of the written language across which he stumbles echoes European explorers’ for-ays into Egypt before the decipherment of hieroglyphs.

Debelius also proposes the influence of H. Rider Haggard on Wells, ‘as if the best- selling author of imperial adventure fiction had somehow left his ghostly signature on Wells’ text’.72 The Time Machine shares several features in common with Haggard’s She of the previous decade, although one symbolic parallel stands out in particular. As Haggard’s protagonists approach the landmass on which they will find the lost civilisation of Kôr, their crossing of this boundary is overseen by ‘a gigantic monument fashioned, like the well- known Egyptian Sphinx, by a forgotten people … perhaps as an emblem of warning’.73 There is far more that might be said in drawing connections between these texts; suffice it to say that the sphinxes in both cases mark the shift from the known world into a fantastical space and that, whether this space exists in the present or in the future, it is imbued both with a sense of ‘pastness’ and ‘primitive’ dangers.

The Time Machine is interested in archaeology, geology, and their legacies, evident not just in the symbol of the sphinx, but in the Time Traveller’s foray into the Palace of Green Porcelain. This is the largest surviving structure in this part of future London, sporting an ‘Oriental’ ‘façade’.74 Its original function as a museum leads the Time Traveller to declare it ‘the ruins of some latter-day South Kensington’.75 Patrick Parrinder interprets the Palace of Green Porcelain as a hybrid of the several museums in South Kensington that were funded by the Crystal Palace as it was originally conceived, along with the Crystal Palace as it was reimagined at Sydenham.76 Robert Crossley proposes that ‘Wells’s Palace is … a composite of several English museums as they existed at the close of the nineteenth century: notably, the British Museum in Bloomsbury’ in addition to ‘the complex of museums in South Kensington’ proposed by Parrinder.77 For Crossley, ‘Wells was accomplishing in fiction and in the future what was dreamed of by Prince Albert in the nineteenth century: a single grand institution that … would not separate “natural history” from human artifacts in the study of culture’. Its eclectic collections, the Time Traveller hypothesises, might incorporate ‘a great deal more … than a Gallery of Palæontology … historical galleries … even a library’.78 Unlike Crossley, I read the Palace of Green Porcelain as a reversion back to an earlier type of museum with less rigid differentiations between its different types of collections. Indeed, the eclectic exhibits of the Palace of Green Porcelain seem closer to the Wunderkammer out of which several nineteenth- century museums developed. The British Museum, which originated in the collections of the British physician Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), is one such example. The Palace of Green Porcelain’s collections recall those of the British Museum before the creation of the Natural History Museum in 1881, as natural history exhibits give way to antiquities: walking through the museum, the Time Traveller observes ‘[a] few shrivelled and blackened vestiges of what had once been stuffed animals, desiccated mummies in jars that had once held spirit, a brown dust of departed plants’, and shortly thereafter ‘a vast array of idols – Polynesian, Mexican, Grecian, Phœnician, every country on earth’.79 This is evidently a step backwards from the separate departments of the British Museum, whereby artefacts were contextualised with other examples from the same civilisation of origin.

The Time Traveller himself even reverts to outdated forms of Egyptology in his encounter with the white sphinx, once he has realised that the Morlocks have secreted his time machine inside the pedestal upon which the statue stands. In a nod to the work of Giovanni Battista Caviglia, who was partially responsible for the excavation of the Great Sphinx in the 1810s and some of whose excavations at Giza involved the use of gunpowder, the Time Traveller speculates that had he found explosives in the Palace of Green Porcelain he would have ‘blown Sphinx, bronze doors, and … my chances of finding the Time Machine, all together into non-existence’.80 Far from the careful, meticulous archaeological processes of the 1890s, the methods considered by the Time Traveller in his desperation recall the destructive methods of Egyptology over half a century earlier. This appears to be part of the cultural degeneration that has not only taken place in the future, in which museum departments have collapsed back in on themselves – but takes place in the Time Traveller himself, in which he reverts to outdated science.

Intriguingly, The Time Machine may have impressed itself upon members of the scientific community interested in Egyptian archaeology and in the longevity of man- made structures over the course of millennia. The opening of astronomer Percival Lowell’s article, ‘Precession: And the Pyramids’ in a 1912 issue of Popular Science Monthly, opens with the author imagining a ‘tourist … transported back in time’ to see the different view of the stars that would have existed ‘five thousand years ago’.81 It is tempting to read in Lowell’s article, with its early allusion to time travel, the influence of Wells’s text. Wells’s Time Traveller, who journeys to a time far from his own (albeit a leap into the future rather than the past) also notes that despite the ‘sense of friendly comfort’ provided by the stars, ‘[a] ll the old constellations had gone’.82 Lowell ends this piece with thoughts inspired by ‘the pyramids … the enduring character of the past besides the ephemeralness of our day’, which have their counterpart in the white sphinx of The Time Machine, a lingering Egyptian presence while most traces of nineteenth-century culture have decayed.83 Although Lowell concedes that the Egyptians did not ‘have printing’, he counters that ‘libraries are not lasting’. There is perhaps a whisper of Wells’s crumbling books in the Palace of Green Porcelain here. While it is difficult to prove a direct line of influence from Wells to Lowell, they were very much thinking on the same wavelength.

More certain is the influence of Wells’s time-travel fiction on Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet. One of the children’s trips to the future takes them to the British Museum, perhaps in an allusion to the Time Traveller’s visit to the Palace of Green Porcelain on his own journey. Like the landscape imagined in Wells’s novella, at least at first glance, London of the future in The Story of the Amulet is a pastoral idyll: the Museum is surrounded by ‘a big garden, with trees and flowers and smooth green lawns’.84 The ‘white statues’ which ‘gleamed among the leaves’ even recall the white sphinx amidst this lush landscape. Here, in a far less distant future than Wells had imagined, the children encounter a boy called Wells, named ‘after the great reformer’ of the children’s own time: Nesbit’s ‘friend and fellow Fabian socialist’.85

Nesbit’s time- travel fiction is, despite these allusions to Wells’s ear-lier work, enormously different to The Time Machine. Despite this, Nesbit’s text, too, emphasises London’s saturation with relics from the ancient past. The children’s home in this story is that of their ‘old Nurse, who lived in Fitzroy Street, near the British Museum’. The rooms of the ‘learned gentleman on the top-floor’ – an Egyptologist called Jimmy – are themselves filled with antiquities including a ‘very, very, very big’ mummy- case (an illustration of which appears both in the book and stamped in gold on the book’s front cover). This means that the spaces that the children inhabit–even before their adventures through space and time – are heterotopic, whether on a macro or micro scale: London itself – a city that ‘seems to be patched up out of odds and ends’ – and the house in Bloomsbury, respectively.86 Temporal collapses seem to define the spaces that the children occupy even when they are not travelling to distant civilisations. The aforementioned mummy case seems to change expression to something more benign over the course of the narrative ‘as if in its distant superior ancient Egyptian way it were rather pleased to see them’.87 This is certainly a less threatening presence than Wells’s sphinx.

In Nurse’s parlour, ‘a dreary clock like a black marble tomb … silent as the grave … for it had long since forgotten how to tick’ is an early symbolic indication that this is a space of no time, or else of all times.88 The clock’s morbid associations conjure up images of mausolea, very much in keeping with the supposedly ‘dead’ civilisations that the children go on to encounter. Another broken timepiece – ‘part of the Waterbury watch that Robert had not been able to help taking to pieces at Christmas and had never had time to rearrange’ – cements this sense that the children are destined to be outside-of-time.89

In fact, differences between the children’s own time and the various civilisations they visit – accessed via portals to different places in time and space created by the amulet, which appear as keyhole-shaped doors – are often pared down. The first instance of time travelling in children’s fiction sees the children, surrounded by ‘the faded trees and trampled grass of the Regent’s Park’, catching a glimpse of ‘a blaze of blue and yellow and red’ within the archway opened up by the amulet.90 Their first view of predynastic Egypt (‘the year 6000 B.C.’) is a sensory bombardment of primary colours suggesting, on the one hand, a kind of visual primitivism, but equally, on the other, of a vibrancy to which the children do not have access in modern London (aside from, one assumes, the technicolour Egyptian Court).91 Nesbit’s description of the ‘faded’ greenery of Regent’s Park, suggests something tired and drab in contrast to the fresher colours of Egypt in the distant past. Despite this, the ‘little ragged children playing Ring o’ Roses’ in the children’s present are more suggestive of older pagan traditions than of any kind of cultural modernity, the circular formation of Ring o’ Roses later taken up by the protagonists as they travel back to ancient Britain and by the children they witness there.92

This lack of easy differentiations between places and times continues throughout The Story of the Amulet. A British settlement in 55 BCE reminds the children of ‘the old [predynastic] Egyptian town’ they have previously visited.94 The children’s later visit to Egypt in the time of Joseph, which has them remarking that ‘[t] he poor Egyptians haven’t improved so very much in their building’, also contributes to this sense of cultural stagnation across times and geographies.95 When the children encounter an Egyptian worker calling their ‘comrades’ to ‘strike’, one of the children, Robert, observes that he ‘heard almost every single word of that … in Hyde Park last Sunday’; moreover, Egyptians who utter disparaging remarks similar to those of their modern counterparts at hearing this call to action would ‘nowadays … have lived at Brixton or Brockley’, according to Nesbit’s omniscient narrator.96

Nesbit’s novel, as this tongue-in-cheek comment suggests, is one which treats its subject matter with humour, and Nesbit credits the children’s adventures in the past with sparking major historical events that have lasting cultural repercussions, namely Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain, and the introduction of currency to ancient Egypt. Referring to the latter, the narrator jests, ‘You will not believe this, I daresay, but really, if you believe the rest of the story, I don’t see why you shouldn’t believe this as well’.97 Belief is, in fact, crucial to the amulet’s magical facilitation of time travel. As various characters relate over the course of the novel, ‘time is only a form of thought’. Think differently, Nesbit implies (and, if you are an adult reader, with the imagination of a child), and time travel is within easy reach. Joanna Paul reads the novel’s magic as being the power of ‘the written word’ in granting the reader access to different points in space and time, an interpretation of the book itself as magical amulet or, indeed, time machine.98

Likewise, Nesbit treats magical and esoteric subjects with a wry smile. Jimmy, the ‘learned gentleman’ who lives on the top floor, believes that he is communicating details of antiquity to the children through ‘thought- transference’, at one point speculating ‘perhaps I have hypnotised myself’.99 Nesbit seems to enjoy the tension between the genuine supernatural or magical versus mythology, fakery, and illusion. One of Jimmy’s friends ridicules ‘thought-transference’ as ‘simply twaddle’ before telling the novel’s child protagonists about Atlantis – as a real historical place – a mere page later.100 Indeed, encounters with the magical actually suggest the lack of truth to other phenomena, as if there can only be so much enchantment in the world; after visiting Atlantis, Jimmy ‘ceased to talk about thought- transference. He had now seen too many wonders to believe that.’101

As U. C. Knoepflmacher records, Nesbit ‘supported radical causes and esoteric cults such as the theosophy espoused by Madame Blavatsky’, these interests manifesting in The Story of the Amulet. The novel hints, in the episode of the little girl called Imogen, who the children reunite with her mother in another time, that other forms of time travel – namely, reincarnation – feature in Nesbit’s universe. Another humorous moment in which the queen of Babylon, transported to the children’s present, is assumed to be the British theosophist and socialist Annie Besant, further suggests the indistinguishability between the cultures of the ancient past and modern present. Theosophy’s influence can also be detected in the children’s Atlantean excursion and in its incorporation of reincarnation into its mythology.102 If we read Nesbit’s novel as informed by esotericism, we can certainly perceive the influence of Ignatius Donnelly, whether first or second hand, in the novel’s presentation of Atlantis as an origin point for human civilisation, and specifically in its suggestion of the Egyptians as the inheritors of Atlantean knowledge. As Joanna Paul observes, ‘Nesbit’s Atlantis is primarily the Atlantis of Plato’, though unlike in Plato – but typical of nineteenth-century esoterica and pseudoscience – Atlantis is held aloft as the pin-nacle of human civilisation.103