These historians built bridges across centuries, and across cultures.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The medieval world was, in many respects, a world of memory. Across civilizations and continents, the task of recording, interpreting, and transmitting the past fell to a unique class of intellectuals: the historiographers. Far from being mere chroniclers, these figures shaped cultural memory, legitimized dynasties, encoded moral and spiritual ideals, and articulated the rhythms of continuity and rupture. Here I survey prominent medieval historiographers from Europe, Asia, the Near East, and the indigenous Americas, exploring their methods, motivations, and cultural roles within the societies they serve.

Europe: From Monastic Chronicles to Royal Histories

Overview

In medieval Europe, historiography was deeply embedded in religious life. The collapse of Roman bureaucratic structures left the preservation of historical memory largely in the hands of the Church. Monasteries became the primary loci of intellectual activity, and their scribes recorded both sacred and secular events in Latin.

Throughout Europe, medieval historiographers were both shaped by and shapers of power. Whether monastic chroniclers or court-sponsored writers, they wrote not only to record events but to cultivate a moral and cosmic coherence in a world defined by divine order.

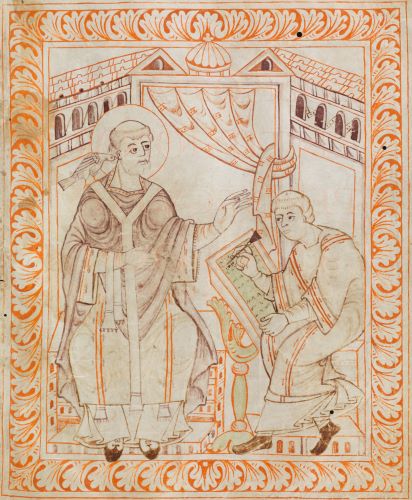

Bede the Venerable (c. 672–735)

Bede, an Anglo-Saxon monk of the Northumbrian monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow, remains one of the most influential historiographers of early medieval Europe and stands as the archetype of early medieval historiographers in the West. His Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (“Ecclesiastical History of the English People”), completed in 731, not only chronicled the development of Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England but effectively constructed a national narrative in a time of fragmented tribal identities and uncertain political borders.1 Bede’s method was distinctive for its combination of theological vision and empirical rigor. He employed Roman chronological systems (notably the Anno Domini dating popularized through his work), collected oral testimony with care, and synthesized earlier annals and correspondence into a coherent whole.2 Bede understood history as a providential unfolding of divine will, and in this regard his work bears the marks of Augustinian historiography. Yet he was no mere compiler. His judgments—such as his critique of British resistance to Roman ecclesiastical norms—demonstrate a clear interpretive framework rooted in ecclesial unity and spiritual hierarchy.3 By integrating biblical typology with documentary practice, Bede offered not only a record of conversion but a moral landscape in which the Anglo-Saxon world could locate its identity and divine favor.

Bede’s influence extended far beyond his immediate monastic circle. His historical writing became foundational for medieval English identity and ecclesiastical authority, shaping perceptions of kingship, sanctity, and national destiny for centuries.4 Latin copies of the Historia Ecclesiastica circulated widely across the Carolingian and Ottonian realms, where scholars and clerics viewed Bede as both a model of Christian learning and a transmitter of Romanitas in the post-Roman world.5 His work’s authority derived not only from its detailed annalistic structure and scriptural resonances but also from the implicit argument it advanced: that history was a divine pedagogy, and the Church the vessel of cultural continuity. This theological premise gave meaning to historical events as more than sequences of power; they became moral lessons encoded into time itself.6 Bede’s historiography thus straddled the line between chronicle and confession, science and sermon, setting a precedent that would define medieval historical writing for generations. In the end, Bede was not merely a historian of England but a historian for Christendom, remembered rightly as the father of English history and one of the last great voices of patristic culture in the Latin West.7

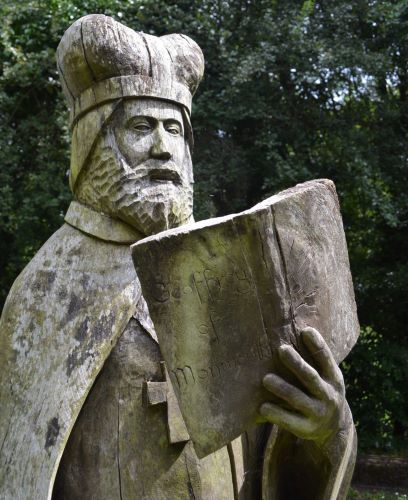

Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100–1155)

By the twelfth century, historiography evolved with the rise of universities and vernacular literature. Geoffrey of Monmouth, a cleric and magister likely of Breton-Welsh descent, played a pivotal role in the construction of medieval British identity through his magnum opus, Historia Regum Britanniae (“The History of the Kings of Britain”), completed around 1136.8 Though often dismissed by modern historians as a writer of legend rather than fact, Geoffrey’s importance lies not in empirical accuracy but in mythopoeic invention. Drawing on obscure Welsh sources, oral traditions, and his own creative instincts, Geoffrey crafted a sweeping narrative of Britain’s past, tracing its foundation to Trojan exile Brutus and culminating in the reign of King Arthur, whom he transformed from a folkloric figure into a pan-British imperial ideal.9 In doing so, he not only gave Britain a heroic antiquity rivaling that of Rome but also provided a charter myth for Norman rulers seeking legitimacy over the diverse and restive peoples of the British Isles. Geoffrey’s Arthur is not the chivalric knight of later romance, but a conqueror-king whose dominion stretches from Scotland to Gaul, embodying the unity and glory Norman kings aspired to project.10 His history, translated into multiple languages and adapted widely, catalyzed an enduring Arthurian tradition that would dominate European literature and political imagination for centuries.

Despite its legendary tone, Geoffrey’s Historia must be understood within the broader context of twelfth-century historiography, which blurred the lines between memory, myth, and political aspiration. In a period often referred to as the “Twelfth-Century Renaissance,” there emerged a renewed interest in classical learning, genealogy, and the moral purpose of history—concerns which Geoffrey’s work reflects in full.11 His portrayal of Arthur as a rex quondam et futurus (once and future king) resonated deeply in a Britain still fractured by dynastic conflict and cultural fragmentation. Even his depiction of figures like Merlin—presented for the first time in a sustained literary narrative—was a fusion of Welsh prophecy, Christian typology, and political commentary.12 Scholars such as J.S.P. Tatlock have argued that Geoffrey intended not deception but literary nation-building, a synthesis of ethnic memories and ideological needs.13 His work was immensely influential: it served as a source for later chroniclers such as Wace and Layamon, shaped Plantagenet royal ideology, and framed insular historiography well into the early modern period. Geoffrey of Monmouth, therefore, cannot be dismissed merely as a fabulist; he was a historiographer in the fullest medieval sense—one who forged history not only from what was remembered but from what needed to be believed.14

Suger of Saint-Denis (c. 1081–1151)

Suger of Saint-Denis, abbot, royal advisor, and patron of the arts, was a central figure in the cultural and political life of Capetian France. Though better known for his pioneering role in the development of Gothic architecture, particularly in the reconstruction of the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, Suger was also a historiographer of notable subtlety and purpose. His works, especially the Vita Ludovici Grossi Regis (“Life of King Louis the Fat”) and the Deeds of Louis the Fat, written in the 1140s, function both as panegyric and political instruction.15 Far from being mere hagiography, these texts offer a pointed defense of royal authority and clerical reform, casting King Louis VI as the protector of ecclesiastical order and restorer of justice in a fragmented feudal society.16 Suger’s historiography was intimately tied to his role as a statesman; as one of the king’s closest confidants, he used narrative to frame Louis’s reign as divinely sanctioned and morally necessary, positioning the monarchy as a counterbalance to both rebellious barons and papal overreach.17 The stylistic and rhetorical strategies he employed—biblical typology, classical allusion, and moral exempla—demonstrate the interpenetration of classical learning and Christian theology that typified the twelfth-century renaissance.

Suger’s historiographical vision was inseparable from his architectural and administrative achievements at Saint-Denis, which together articulated a theology of order and light expressive of the emerging Capetian ideology. His narratives mirror the symbolic program of the rebuilt abbey church, where political theology was etched into stained glass and sculpted stone.18 By documenting the king’s victories over disorder, Suger did not merely record events; he created a sacred history that linked Capetian kingship to the Carolingian past and apostolic mission of France. Moreover, his texts are among the first to reflect a nascent concept of France as a unified realm under divinely guided monarchy, presaging the more centralized royal historiography of later centuries.19 Unlike monastic chroniclers focused inwardly on abbey life, Suger directed his historical lens outward—toward statecraft, diplomacy, and moral governance—writing as both a participant and a shaper of political memory. His work thus bridges the monastic and royal traditions of historiography, offering a vital perspective on how religious figures in the High Middle Ages helped craft the ideological scaffolding of nationhood and royal sacrality.20

Asia: Imperial Historiography and Philosophical Memory

Overview

In Asia, historiography was a central institution of statecraft and philosophical tradition. Nowhere is this clearer than in China, where the role of official historian had long been sacralized since the Han dynasty. This tradition continued robustly through the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming periods. The Twenty-Four Histories represent a millennia-long commitment to dynastic recordkeeping.

Sima Guang (1019–1086)

Sima Guang (1019–1086), a statesman, Confucian scholar, and pioneering historiographer of the Northern Song dynasty, occupies a central position in the intellectual and political life of medieval China. He was among the greatest compilers of the medieval period. His monumental Zizhi Tongjian, commonly translated as Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government, was completed in 1084 after nineteen years of intensive labor by a team of scholars under his direction.21 Spanning over 1,300 years of Chinese history—from the Warring States period (403 BCE) to the early Tang dynasty (959 CE)—the Tongjian was intended as a practical guide for emperors and officials to learn from the successes and failures of the past.22 Sima Guang’s historiography adhered closely to Confucian principles, emphasizing moral causality, the importance of proper ritual, and the dangers of unchecked ambition and disorder. He deliberately favored narrative continuity and clarity over encyclopedic detail, structuring the work annalistically to allow for the unfolding of causality over time.23 In contrast to the standard dynastic histories, which were organized by subject (e.g., biography, institutions), the Tongjian offered a chronological account that underscored the interplay between ethical governance and the fate of the state. His prose is marked by restraint and precision, serving a didactic function: not merely to record what happened, but to instruct rulers on what ought to happen.

Politically, Sima Guang was a conservative Confucian who opposed the radical reforms of his contemporary Wang Anshi, seeing in them a dangerous deviation from classical precedent and social harmony. His historiography mirrored this ideological stance. While not a reactionary, he believed deeply in the importance of historical memory as a moral compass for governance.24 The Tongjian thus became not only a historical record but also a polemical instrument in the fierce debates over Song dynasty reform. In the centuries that followed, it was widely read and annotated, especially by later scholar-officials and Confucian moralists who saw in Sima Guang a model of integrity, both as a historian and as a minister.25 His influence extended well beyond China: the Tongjian was abridged and adapted during the Yuan and Ming dynasties and became a staple of East Asian statecraft literature.26 Sima Guang’s fusion of documentary precision with ethical interpretation represents a distinctive model of historiography in which history was not a detached chronicle but an active force in the moral education of rulers and society. In this, he stands among the most important historiographers of the medieval world, offering a vision of the past deeply intertwined with the responsibilities of power and the imperatives of virtue.

Al-Biruni (973–1048)

In the Islamicized regions of Central and South Asia, Persian historiography flourished. Abū Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Bīrūnī was one of the most intellectually versatile figures of the medieval Islamic world—astronomer, mathematician, geographer, linguist, and above all, a comparative historiographer of rare scope. A native of Khwarezm (in modern-day Uzbekistan), al-Biruni spent much of his scholarly life in the cosmopolitan court of the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud, whose conquests in South Asia provided the historian with unprecedented opportunities to study Indian civilization firsthand. His most renowned historical work, Kitāb al-Hind (The Book of India), written circa 1030, is a masterpiece of cross-cultural historiography, ethnography, and comparative religion.27 Far from being a mere chronicle of conquest, the Kitāb al-Hind presents a systematic, respectful, and remarkably objective account of Indian customs, beliefs, languages, and sciences.28 Al-Biruni studied Sanskrit, consulted Brahmanical texts, and interviewed native scholars, all while maintaining a critical but deeply inquisitive stance. He explicitly disavowed polemic, declaring his intent to describe Indian thought “as it is,” not as filtered through Islamic or Persian preconceptions.29 In this way, al-Biruni’s historiography anticipates modern anthropological approaches and marks a departure from the annalistic and court-centered traditions that dominated Islamic historical writing in his era.

Yet al-Biruni’s work was not detached from the moral and intellectual currents of his time. As a devout Muslim and a product of the Islamic Golden Age, he situated his inquiry within a broader framework of divine unity and universal reason. His comparative method—juxtaposing Indian metaphysics with Islamic theology and Greek philosophy—sought common rational ground among civilizations.30 Unlike historians writing to glorify rulers or sanctify religious narratives, al-Biruni employed historical knowledge as a tool for intercultural understanding and epistemological humility. His treatment of time, calendars, cosmologies, and rituals across cultures demonstrated a unique awareness of the cultural relativity of historical experience.31 Moreover, al-Biruni’s other major works, such as his Chronology of Ancient Nations (al-Āthār al-Bāqiya), reflect his conviction that historical memory must be rooted in empirical observation, mathematical precision, and comparative logic.32 al-Biruni occupies a singular place in medieval historiography: a polymathic outsider who recorded history not from the perspective of power or piety alone, but from an insatiable curiosity about the human condition across civilizations.

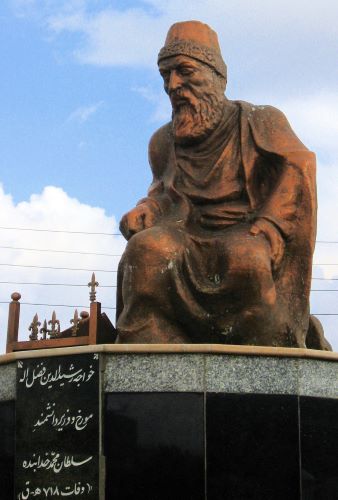

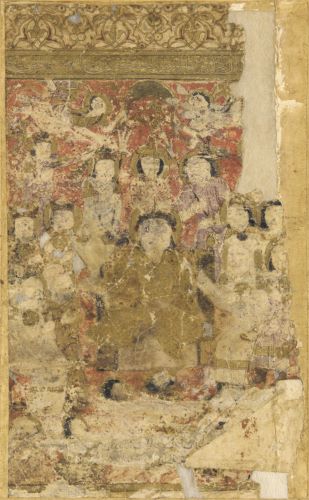

Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318)

Rashid al-Din Fazlullah Hamadani, a Persian polymath, physician, and vizier to the Ilkhanid court of Mongol Persia, stands as one of the most ambitious and influential historiographers of the medieval Islamic world. His magnum opus, the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh (“Compendium of Chronicles”), completed around 1310, was commissioned under the patronage of Ghazan Khan and continued under Öljaitü.33 It represents one of the first concerted efforts to write a comprehensive universal history, encompassing not only the Mongols and Islamic dynasties, but also the Chinese, Indians, Franks, and Jews. Rashid al-Din’s work blended Persian bureaucratic methods with Mongol imperial ambitions, drawing on sources in Arabic, Persian, Turkic, and even Chinese, some of which were relayed through translators and scribes embedded within the Ilkhanid administrative apparatus.34 The Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh was intended not merely as an archive of memory but as a legitimizing ideological project: it placed the Mongols within the historical continuum of world empires, from the biblical and Sasanian kings to the Islamic caliphates, framing their conquests as a new cosmopolitan order rather than barbaric disruption.35 Rashid al-Din’s methodological innovations—his use of diverse sources, concern for chronology, and commitment to ethnographic accuracy—marked a watershed in Islamic historiography, extending the scope and function of historical writing far beyond dynastic chronicles.

Rashid al-Din’s project reflected both the pluralism and precariousness of his position. As a Jewish convert to Islam, and a bureaucrat serving a Mongol regime still negotiating its post-conquest identity, Rashid was uniquely positioned at the crossroads of cultures and epistemologies.36 His historical imagination was deeply shaped by the multiculturalism of the Ilkhanid court, which aspired to emulate the universal sovereignty of Chinggis Khan while accommodating Islamic norms of legitimacy and order.37 The Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh not only chronicled political events but also included extensive sections on geography, medicine, natural history, and religious beliefs—a testament to Rashid’s encyclopedic vision and the holistic intellectual ethos of the time.38 Though later Islamic scholars occasionally questioned his reliability due to his courtly affiliations and non-Arab origin, Rashid’s work endured as a model of administrative historiography and imperial ideology. His tragic downfall—accused of poisoning Öljaitü and executed in 1318—only underscores the volatile entanglement of history, power, and politics in his era.39 Yet despite his fall, Rashid al-Din’s legacy persisted. His chronicle would inform later Persian, Ottoman, and even Chinese historical traditions, earning him a place not only as a key chronicler of Mongol imperialism but as a precursor to global history itself.

Japan

In Japan, historiography took on a literary and philosophical character. The Nihon Shoki (compiled in 720) and later works like The Tale of the Heike (13th century) recorded court intrigues, religious visions, and warrior valor, all filtered through Buddhist impermanence (mujo) and Confucian duty. Unlike in China, where historical writing was bureaucratic, Japanese historical memory often expressed itself through narrative elegance and fatalistic tone.

The Near East: Sacred Histories and Imperial Legacy

Overview

The medieval Islamic world produced one of the richest historiographical traditions of the era, characterized by rigorous source criticism, theological engagement, and narrative sophistication.

al-Tabari (839–923)

Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, the great Persian historian, jurist, and Qurʾānic exegete of the Abbasid era, is widely recognized as the preeminent compiler of early Islamic history. His Taʾrīkh al-rusul wa’l-mulūk (History of the Prophets and Kings), commonly known as Tarikh al-Tabari, is a monumental chronicle that extends from the creation of the world to the early tenth century, with a particular focus on the Islamic community from the Prophet Muhammad through the early Abbasid caliphate.40 Al-Ṭabarī’s historiographical method is deeply rooted in the isnād tradition—chains of transmission used to verify reports in hadith literature—and his critical use of sources sets him apart from many of his contemporaries.41 His approach often involves presenting multiple, sometimes contradictory accounts of the same event, with minimal editorial intrusion, thereby allowing the reader or jurist to evaluate the reliability and implications of each narrative.42 This method reflects not only al-Ṭabarī’s scholarly scrupulousness but also the legal and theological ethos of the period, in which truth was to be discerned through careful examination of authenticated transmission. His History serves not only as a vital record of early Islamic expansion and internal conflict but also as a window into the construction of historical authority in the medieval Islamic world.

Al-Ṭabarī’s historiography must be understood within the context of his broader intellectual project, which included his famous Qurʾānic commentary, Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī. Both his Tafsīr and his History reveal a scholar engaged in synthesizing vast and sometimes conflicting bodies of knowledge into structured, accessible forms.43 His work reflects the cosmopolitan nature of Abbasid Baghdad, where scholars of various linguistic, ethnic, and sectarian backgrounds engaged in a shared pursuit of textual mastery and historical coherence. While al-Ṭabarī remained a devout Sunni and upheld traditionalist interpretations, his willingness to preserve accounts from Shiʿi and even non-Muslim sources demonstrates a methodological inclusivity rare for his time.44 In this way, his Tarikh is not merely an Islamic history but an ecumenical archive of the early medieval Near East. Despite its encyclopedic scope, his work was also political in subtle ways, particularly in how it frames the legitimacy of rulers and the unfolding of divine justice through history.45 Later historians—both Islamic and Western—relied heavily on al-Ṭabarī’s account, making him not only a foundational figure in Islamic historiography but also a crucial intermediary between oral tradition, early Islamic memory, and written narrative. His chronicle stands as a benchmark of Islamic historical writing, offering both the density of tradition and the openness of inquiry that characterized classical Islamic scholarship at its height.

Ibn al-Athir (1160–1233)

ʿAlī ibn al-Athīr, a prominent historian of the late Abbasid and early Ayyubid periods, authored one of the most important Islamic universal chronicles of the medieval period: al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh (“The Complete History”). Writing from Mosul during a time of political turbulence and military upheaval, Ibn al-Athīr sought to continue and refine the historical tradition established by al-Ṭabarī while incorporating developments of the intervening centuries.46 His chronicle spans from the creation of the world to the year 1231, synthesizing earlier accounts with contemporary events, especially those involving the Crusades and the rise of the Seljuks, Zengids, and Ayyubids. Ibn al-Athīr was both a compiler and a critical analyst; while he borrowed liberally from earlier authorities, he often revised and abridged their material, showing a keen sense of narrative cohesion and thematic structure.47 His attention to causality and political context, particularly in his accounts of warfare and diplomacy, reflects a sophisticated historiographical technique that aimed not merely to preserve memory but to offer coherent and instructive narratives for a turbulent Islamic world. His detailed and often poignant accounts of the Crusades from a Muslim perspective have made his chronicle an indispensable counterbalance to Latin sources such as William of Tyre and the Gesta Francorum.

Ibn al-Athīr’s historical method was shaped by his engagement with both theological concepts and pragmatic politics. While grounded in a Sunni worldview, he did not allow sectarian polemic to dominate his narrative. Instead, he presented a complex picture of Islamic history, highlighting the moral and spiritual consequences of disunity among Muslim polities, particularly in the face of external threats like the Crusaders and the Mongols.48 His writing exhibits a deep awareness of political decline, particularly during the later Abbasid period, and he frequently laments the absence of effective leadership and unity within the ummah.49 Yet his critique is never nihilistic; rather, it is undergirded by a conviction in the moral obligations of rulers and the enduring relevance of divine justice. Ibn al-Athīr’s al-Kāmil became one of the most widely read and cited Islamic chronicles in later centuries, influencing historians from the Mamluk to the Ottoman periods.50 His fusion of theological sensibility, narrative clarity, and political realism exemplifies the mature form of Islamic historiography in the post-classical period. More than a record of events, his chronicle stands as a reflection on the burdens of leadership, the impermanence of power, and the necessity of historical consciousness in a world perpetually in flux.

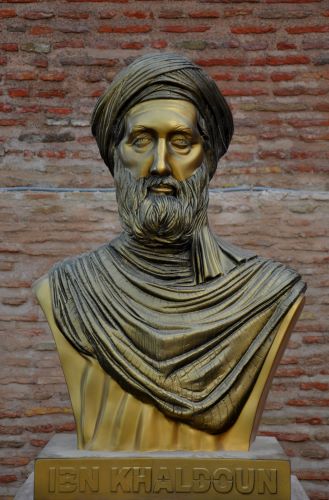

Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406)

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn Khaldūn, the North African historian, jurist, philosopher, and political theorist, stands as perhaps the most innovative historical thinker of the medieval world. His masterwork, the Kitāb al-ʿIbar, and its famous introduction, the Muqaddimah (“Prolegomena”), mark a profound departure from conventional Islamic historiography.51 Writing in the context of the late Marinid and Hafsid states—amid dynastic decline, plague, and social upheaval—Ibn Khaldūn sought to uncover the underlying causes of civilizational rise and fall. Rejecting the purely narrative or anecdotal approaches of many of his predecessors, he theorized history as a science governed by discoverable laws.52 Central to his framework is the concept of ʿaṣabiyyah (social cohesion or group solidarity), which he posited as the driving force behind the formation and decay of political order. According to Ibn Khaldūn, dynasties emerge from desert tribes whose cohesion enables conquest, but as luxury and bureaucracy take root, ʿaṣabiyyah fades, leading inevitably to decline.53 This cyclical view of history, grounded in empirical observation and theoretical abstraction, makes Ibn Khaldūn the first true historical sociologist—centuries ahead of Machiavelli or Vico in the West.

The Muqaddimah is not merely a historical introduction but a wide-ranging treatise that integrates economics, education, geography, demography, and theology into a unified theory of society. Ibn Khaldūn’s methodological skepticism—his insistence on corroborating sources, evaluating biases, and interpreting events in their social and environmental contexts—reflects a radically critical historiographical stance.54 He also criticized contemporary historians for credulity and courtly sycophancy, arguing that proper history requires both data and interpretive intelligence.55 While his work remained relatively obscure in the Islamic East for centuries, it was preserved and revered in the Maghrib and al-Andalus, and eventually rediscovered by European Orientalists in the nineteenth century, who hailed him as a proto-modern thinker.56 In truth, Ibn Khaldūn’s historical thought resists such reduction: he was both deeply embedded in Islamic intellectual traditions and strikingly original in his analytic method. His legacy continues to resonate not merely as a historian of the Arab-Islamic world but as a foundational figure in the philosophy of history itself. In placing human society at the center of historical causality, Ibn Khaldūn not only transformed medieval Islamic historiography but prefigured entire fields of modern social science.

The Indigenous Americas: Oral Memory, Codices, and Colonial Encounters

Overview

While the civilizations of the Americas did not produce historiography in the form of textual narrative prior to European contact, they cultivated sophisticated systems of historical memory through oral traditions, pictographic writing, ritual performance, and architecture.

Codices

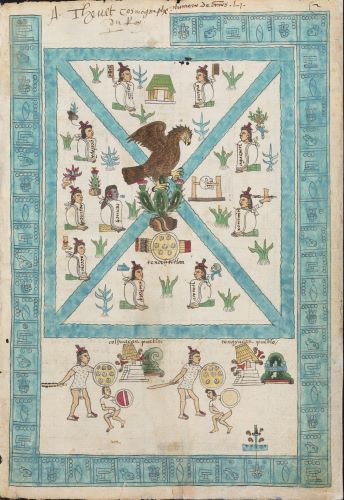

In Mesoamerica, the Aztec codices—such as the Codex Mendoza and the Codex Boturini—blend historical record, genealogical lists, and mythic time. These codices, created on amate bark or deerskin, conveyed dynastic legitimacy, ritual calendrics, and conquest narratives through highly symbolic iconography. Aztec historians, known as tlacuiloque, worked under royal patronage to record the sacred and political past, often blending linear time with cyclical myth.

The Codex Mendoza, compiled circa 1541 in the aftermath of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, stands as a vital source for understanding the historiographical practices and sociopolitical structure of pre-Columbian and early colonial Mesoamerica. Commissioned by Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of New Spain, and intended for Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire, the manuscript combines indigenous pictorial narrative with Spanish annotations, producing a unique hybrid historical document.57 It is divided into three parts: the first recounts the dynastic history of the Aztec rulers and their conquests; the second records tribute lists from subject provinces; and the third describes daily life, education, social customs, and legal norms within Mexica society. The codex’s visual system was constructed by Nahua tlacuiloque (scribe-painters), trained in pre-Hispanic traditions of symbolic representation, who rendered events in a pictographic format intelligible to native readers while Spanish glosses, likely based on indigenous oral interpretations, rendered them accessible to European audiences. This collaborative medium reflects the epistemological encounter between colonial power and indigenous memory, with the result being both a continuity and transformation of historical narrative. Scholars have debated the extent to which the codex preserves an “authentic” indigenous historiography, but it is clear that its core structure—dynastic succession, military expansion, and tribute documentation—mirrors traditional Nahua modes of encoding historical legitimacy and sacred power. In this sense, the Codex Mendoza is not only a colonial artifact but also a continuation of a deeper Mesoamerican tradition of history-as-sovereignty, where visual and spatial cues conveyed time, moral order, and imperial destiny.

The Codex Boturini, also known as the Tira de la Peregrinación (“Scroll of the Migration”), is a crucial example of pre-Hispanic-style indigenous historiography composed during the early colonial period, likely in the mid-16th century. Uniquely rendered on amatl (bark paper) in a continuous scroll format, the codex presents a visual narrative—entirely without alphabetic text—chronicling the legendary migration of the Mexica from Aztlan to the Valley of Mexico, culminating in the founding of Tenochtitlan.58 Comprising a series of pictographs and iconographic conventions, including footprints, temples, speech scrolls, and glyphs for years and locations, the Codex Boturini encodes a sacred geography in which mythic and historical time are entwined. Unlike the more administrative Codex Mendoza, the Boturini reflects an indigenous temporal sensibility rooted in movement, ritual, and prophecy, portraying the Mexica not as a static polity but as a people divinely destined to found a cosmic center. Its style is consistent with earlier Nahua visual traditions, showing no European influence in format or content, suggesting it was composed by native tlacuiloque drawing from orally transmitted memory and ceremonial knowledge. Scholars such as Elizabeth Boone have emphasized the codex’s function not merely as a record but as a performative mnemonic device, likely used in ritual contexts or to affirm communal identity under colonial rule. The Codex Boturini exemplifies the resilience of indigenous modes of historiography: even after conquest and forced conversion, Nahua intellectuals maintained visual and symbolic structures that articulated a history inseparable from cosmology, migration, and divine election. As such, it remains one of the most culturally autonomous expressions of native historical consciousness from colonial Mesoamerica.

Quipu and Amautas

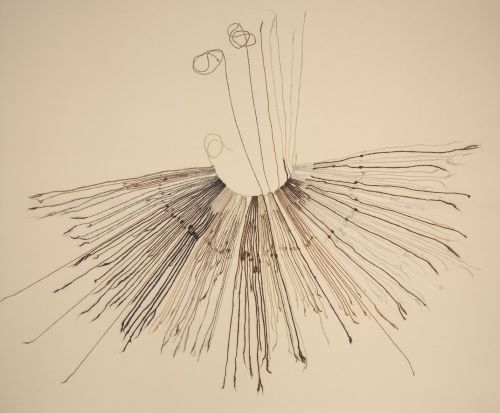

The Inca civilization, lacking a true writing system, preserved history through quipu—knotted cords used for recordkeeping—and amautas (wise men) who memorized vast bodies of oral history, including epic poems and genealogies. Inca rulers employed these traditions to legitimize their divine ancestry and conquest policies.

The quipu—an assemblage of knotted strings used by the Inca and earlier Andean civilizations—served as the primary medium for recordkeeping and historical memory in the absence of a written script, embodying a complex and still partially undeciphered system of data storage. While traditionally viewed as an accounting tool for census, taxation, and resource management, recent scholarship has increasingly emphasized the quipu’s historiographical and narrative potential.59 Structured through variations in knot type, color, fiber, length, and positional hierarchy, quipus could encode calendrical data, genealogies, tribute obligations, and possibly mytho-historical accounts, forming an intricate semiotic system deeply integrated into Inca statecraft and cosmology. Spanish chroniclers such as Garcilaso de la Vega and Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala reported that quipucamayocs—the trained keepers and interpreters of quipus—could “read” them aloud, recounting not only economic data but ancestral stories, dynastic successions, and ritual histories. This suggests a dual function: both administrative and mnemonic, anchoring communal identity in embodied, oral performance rather than in alphabetic text. Scholars like Frank Salomon have argued that quipus functioned as “textiles of history,” woven into social practice and collective memory through ritual and elite transmission. Surviving examples—most of which are fragmentary and lack contextual interpretation—reveal a system that was both materially exacting and culturally fluid, adapting to local needs across the Inca empire. As such, the quipu stands as a non-alphabetic yet intellectually rigorous alternative to Western historical writing, challenging modern assumptions about the limits of literacy and the forms through which historical consciousness may be expressed.

In the Inca world, the amautas—elite sages, philosophers, and educators—played a central role in preserving and transmitting historical, moral, and cosmological knowledge through oral tradition and ritual performance. As members of the learned class within the yanakuna system, amautas were entrusted with the education of young nobles (yachaykuna) at institutions like the Yachaywasi (“house of knowledge”) in Cuzco, where they taught language, religion, statecraft, and the empire’s sacred history.60 Their instruction did not rely on alphabetic writing, but instead drew on memorization, song, poetic structure, and dramatized performance to encode and transmit dynastic genealogies, origin myths, military campaigns, and calendrical cycles. These histories, though not fixed in written form, were rendered stable through social consensus and the authority of ritual repetition, establishing amautas as oral historians whose role paralleled that of literate chroniclers in text-based societies. Spanish sources, including Garcilaso de la Vega and Blas Valera, acknowledged their centrality in shaping Inca identity and legitimacy, describing them as guardians of tradition and interpreters of divine will. Their knowledge was often synchronized with the work of the quipucamayocs, allowing for a dual system of recordkeeping in which knotted cords encoded data and oral discourse preserved narrative meaning.61 Despite colonial suppression and forced Christianization, the intellectual legacy of the amautas persisted in Andean communities, where their influence can be traced in syncretic rituals, moral didacticism, and the continued use of oral genres to affirm indigenous memory. As non-literate yet epistemologically sophisticated figures, the amautas challenge modern notions of historiography by demonstrating that deep historical consciousness need not depend on writing but can flourish through embodied, performative, and communal modes of remembering.

Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl (c. 1578–1650)

The arrival of Europeans transformed these traditions profoundly. Indigenous historiographers used Spanish writing to preserve pre-Columbian histories, often blending Nahua worldview with Christian frameworks. These post-conquest historiographies reflect both cultural loss and resilience, as indigenous elites sought to assert identity and memory under colonial rule.

Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, a mestizo nobleman descended from both the pre-Hispanic rulers of Texcoco and the Spanish colonial elite, stands as a crucial figure in the preservation and transformation of Nahua historical consciousness in colonial New Spain. Writing in Spanish while drawing from Nahuatl oral traditions and pre-conquest annals, Alva Ixtlilxóchitl produced a body of historical works—including the Relaciones Históricas and the Historia de la nación chichimeca—that blended indigenous memory with European chronicle forms.61 His writings aim not only to recount the history of the Acolhua people and their famed ruler Nezahualcoyotl, but also to assert the legitimacy and moral standing of his own lineage in the colonial racial and political hierarchy. Deeply influenced by both Christian humanism and indigenous conceptions of sacred time, Alva Ixtlilxóchitl crafted a syncretic narrative in which pre-Hispanic prophecy, moral virtue, and Christian providence converge. He portrayed the Texcocan kingdom as a refined and just civilization, often implicitly elevating it above both the Mexica and the Spanish in ethical and intellectual terms. His historical method reflects a mestizo epistemology—at once retrospective and strategic—using the tools of the conqueror’s language and script to advocate for the dignity and rights of native nobility within a colonial framework that increasingly marginalized them.62 Despite his elite status and access to archival material, his histories were often neglected or only partially preserved until modern scholars recognized their significance as acts of cultural resistance and narrative preservation. Today, Alva Ixtlilxóchitl is valued not merely as a chronicler but as a historian of intercultural synthesis, whose writings illuminate the tensions and possibilities inherent in indigenous historiography under colonial rule.

Conclusion

Medieval historiographers across continents were not simply recorders of the past—they were its architects. Their work was always more than empirical: it was interpretive, pedagogical, often devotional. Whether a monk in Northumbria, a Confucian scholar in Kaifeng, a Persian polymath in Tabriz, or a tlacuilo in Tenochtitlán, each historiographer shaped history into narrative, memory into meaning. Their texts, however diverse in method or medium, testify to a shared human impulse: to understand the present through the mirror of the past. In their chronicles, we see not only the societies that produced them but also a global medieval consciousness that valued lineage, morality, and cosmological order. In a world fractured by time and empire, these historians built bridges across centuries, and across cultures, reminding us that to write history is to imagine continuity amid change.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. and trans. Bertram Colgrave and R.A.B. Mynors (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), 3.

- R.W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1970), 34.

- Patrick Wormald, “Bede, the Bretwaldas and the Origins of the Gens Anglorum,” in Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society, ed. Patrick Wormald, Donald Bullough, and Roger Collins (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983), 100–129.

- Walter Goffart, The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 235.

- Rosamond McKitterick, History and Memory in the Carolingian World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 78–82.

- J.M. Wallace-Hadrill, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People: A Historical Commentary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 12–15.

- George Hardin Brown, A Companion to Bede (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), 5.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, trans. Lewis Thorpe (London: Penguin Classics, 1966), 51.

- John Gillingham, The English in the Twelfth Century: Imperialism, National Identity and Political Values (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000), 98–102.

- R.R. Davies, The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles 1093–1343 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 33–36.

- Robert Bartlett, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 245–247.

- Richard Barber, The Figure of Arthur (London: Boydell & Brewer, 1972), 12–18.

- J.S.P. Tatlock, The Legendary History of Britain: Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and Its Early Vernacular Versions (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1950), 72–78.

- Jane Tolmie, “The Anglicization of Arthur: The ‘Historia Regum Britanniae’ and the Twelfth-Century Myth of Britain,” Florilegium 15 (1998): 161–178.

- Suger of Saint-Denis, The Deeds of Louis the Fat, trans. Richard Cusimano and John Moorhead (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1992), 3.

- Lindy Grant, Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis: Church and State in Early Twelfth-Century France (London: Longman, 1998), 124–128.

- Walter Cahn, “Suger and the Capetians,” Gesta 23, no. 2 (1984): 95–103.

- Erwin Panofsky, Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946), 14–18.

- Elizabeth A.R. Brown, “The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe,” American Historical Review 79, no. 4 (1974): 1065–1066.

- Robert-Henri Bautier, “The Reign of Louis VI: The Struggle Against the Feudal Aristocracy,” in The Capetian Kings of France: Monarchy and Nation, 987–1328, trans. Michael Jones (London: Macmillan, 1989), 104–110.

- Sima Guang, Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government (Zizhi Tongjian), trans. R.H. Mathews (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1956), 1:ix.

- Peter K. Bol, “This Culture of Ours”: Intellectual Transitions in T’ang and Sung China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 263–267.

- Charles Hartman, Sung Dynasty Uses of the I Ching (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 144–146.

- Paul Jakov Smith and Richard von Glahn, eds., The Song-Yuan-Ming Transition in Chinese History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003), 57–60.

- Stephen C. Angle, Human Rights and Chinese Thought: A Cross-Cultural Inquiry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 96.

- Chun-Chieh Huang, “Ssu-ma Kuang’s Historical Thought and the Development of Chinese Historiography,” Chinese Studies in History 19, no. 3 (1986): 3–27.

- Al-Biruni, Alberuni’s India, trans. Edward C. Sachau, 2 vols. (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1910), 1:xvii.

- Dimitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ‘Abbāsid Society (London: Routledge, 1998), 178–180.

- Al-Biruni, Alberuni’s India, 1:7.

- Thomas F. Glick, Steven J. Livesey, and Faith Wallis, eds., Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia (New York: Routledge, 2005), 64.

- C.H. Beck, “Al-Bīrūnī: A Medieval Anthropologist,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 92, no. 2 (1960): 125–133.

- Al-Biruni, The Chronology of Ancient Nations, trans. C. Edward Sachau (London: W.H. Allen, 1879), 12–14.

- Rashid al-Din, The Successors of Genghis Khan, trans. John Andrew Boyle (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971), xv.

- Charles Melville, “The Illustration of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh and the Art of the Ilkhanids,” in The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy, ed. Reuven Amitai-Preiss and David O. Morgan (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 37–67.

- Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 232–235.

- Sheila S. Blair, “Rashid al-Din and the Visual Culture of the Mongol World,” The Muslim World 94, no. 1 (2004): 55–67.

- Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 22–28.

- Sussan Babaie, “The Mongol Invasions and the Visual Culture of Islam,” in Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands, ed. M. Ekhtiar and M. Sardar (London: Prestel, 2004), 148–152.

- David Morgan, Medieval Persia 1040–1797 (London: Longman, 1988), 82.

- Al-Ṭabarī, The History of al-Ṭabarī: Volume I—General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood, trans. Franz Rosenthal (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 7.

- Chase F. Robinson, Islamic Historiography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 39–41.

- Tarif Khalidi, Arabic Historical Thought in the Classical Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 60–64.

- Claude Gilliot, “Tabari and the Tafsir Tradition,” in The Qur’an: Formative Interpretation, ed. Andrew Rippin (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), 5–25.

- Wadad al-Qadi, “The Religious Foundation of Late ʿAbbāsid Historiography: al-Ṭabarī and the Challenge of the Qaṣṣ,” in Organizing Knowledge: Encyclopaedic Activities in the Pre-Eighteenth Century Muslim World, ed. Gerhard Endress (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 191–231.

- Hugh Kennedy, The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century (London: Longman, 2004), 170–174.

- Ibn al-Athīr, The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh, trans. D.S. Richards, 3 vols. (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006–2008), 1:xv.

- Robinson, Islamic Historiography, 94-96.

- Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 136–139.

- Wadad al-Qadi, “Historiography in the Medieval Islamic World,” in The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 2: 400–1400, ed. Sarah Foot and Chase F. Robinson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 418–421.

- Thomas Walker Arnold and Alfred Guillaume, The Legacy of Islam, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931), 387.

- Ibn Khaldūn, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, abridged and edited by N.J. Dawood (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), xxii–xxv.

- Muhsin Mahdi, Ibn Khaldun’s Philosophy of History: A Study in the Philosophic Foundation of the Science of Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 89–92.

- Ernest Gellner, Muslim Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 16–19.

- Aziz Al-Azmeh, Ibn Khaldun: An Essay in Reinterpretation (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2003), 72–76.

- Khalidi, Arabic Historical Thought in the Classical Perio, 143-146.

- Robert Irwin, Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 182–186.

- Codex Mendoza, ed. Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt, The Essential Codex Mendoza (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 1–4.

- Elizabeth Hill Boone, Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000), 190–194.

- Frank Salomon, The Cord Keepers: Khipus and Cultural Life in a Peruvian Village (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 11–15.

- Frank Salomon and George L. Urioste, eds., The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991), 25–28.

- Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, Selections from the Native Historian of Colonial Mexico, trans. and ed. James Lockhart (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 12–14.

Bibliography

- Al-Azmeh, Aziz. Ibn Khaldun: An Essay in Reinterpretation. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2003.

- Al-Biruni. Alberuni’s India. Translated by Edward C. Sachau. 2 vols. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1910.

- Al-Biruni. The Chronology of Ancient Nations. Translated by C. Edward Sachau. London: W.H. Allen, 1879.

- Al-Ṭabarī. The History of al-Ṭabarī: Volume I—General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989.

- al-Qadi, Wadad. “Historiography in the Medieval Islamic World.” In The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 2: 400–1400, edited by Sarah Foot and Chase F. Robinson, 392–421. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- al-Qadi, Wadad. “The Religious Foundation of Late ʿAbbāsid Historiography: al-Ṭabarī and the Challenge of the Qaṣṣ.” In Organizing Knowledge: Encyclopaedic Activities in the Pre-Eighteenth Century Muslim World, edited by Gerhard Endress, 191–231. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- Allsen, Thomas T. Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, Fernando de. Selections from the Native Historian of Colonial Mexico. Translated and edited by James Lockhart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Angle, Stephen C. Human Rights and Chinese Thought: A Cross-Cultural Inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Arnold, Thomas Walker, and Alfred Guillaume. The Legacy of Islam. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931.

- Babaie, Sussan. “The Mongol Invasions and the Visual Culture of Islam.” In Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands, edited by M. Ekhtiar and M. Sardar, 147–152. London: Prestel, 2004.

- Barber, Richard. The Figure of Arthur. London: Boydell & Brewer, 1972.

- Berdan, Frances F., and Patricia Rieff Anawalt, eds. The Essential Codex Mendoza. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Bartlett, Robert. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950–1350. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Bautier, Robert-Henri. “The Reign of Louis VI: The Struggle Against the Feudal Aristocracy.” In The Capetian Kings of France: Monarchy and Nation, 987–1328. Translated by Michael Jones, 102–120. London: Macmillan, 1989.

- Beck, C.H. “Al-Bīrūnī: A Medieval Anthropologist.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 92, no. 2 (1960): 125–133.

- Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Edited and translated by Bertram Colgrave and R.A.B. Mynors. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

- Blair, Sheila S. “Rashid al-Din and the Visual Culture of the Mongol World.” The Muslim World 94, no. 1 (2004): 55–67.

- Bol, Peter K. “This Culture of Ours”: Intellectual Transitions in T’ang and Sung China. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992.

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill. Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.

- Brown, Elizabeth A.R. “The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe.” American Historical Review 79, no. 4 (1974): 1063–1088.

- Brown, George Hardin. A Companion to Bede. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009.

- Cahn, Walter. “Suger and the Capetians.” Gesta 23, no. 2 (1984): 95–103.

- Davies, R.R. The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles 1093–1343. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Gellner, Ernest. Muslim Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of Britain. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. London: Penguin Classics, 1966.

- Gillingham, John. The English in the Twelfth Century: Imperialism, National Identity and Political Values. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000.

- Gilliot, Claude. “Tabari and the Tafsir Tradition.” In The Qur’an: Formative Interpretation, edited by Andrew Rippin, 5–25. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999.

- Glick, Thomas F., Steven J. Livesey, and Faith Wallis, eds. Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Goffart, Walter. The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Grant, Lindy. Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis: Church and State in Early Twelfth-Century France. London: Longman, 1998.

- Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ‘Abbāsid Society. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Hartman, Charles. Sung Dynasty Uses of the I Ching. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999.

- Huang, Chun-Chieh. “Ssu-ma Kuang’s Historical Thought and the Development of Chinese Historiography.” Chinese Studies in History 19, no. 3 (1986): 3–27.

- Ibn al-Athīr. The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh. Translated by D.S. Richards. 3 vols. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006–2008.

- Ibn Khaldūn. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. Abridged and edited by N.J. Dawood. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Irwin, Robert. Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

- Jackson, Peter. The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century. London: Longman, 2004.

- Khalidi, Tarif. Arabic Historical Thought in the Classical Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Mahdi, Muhsin. Ibn Khaldun’s Philosophy of History: A Study in the Philosophic Foundation of the Science of Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957.

- McKitterick, Rosamond. History and Memory in the Carolingian World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Melville, Charles. “The Illustration of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh and the Art of the Ilkhanids.” In The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy, edited by Reuven Amitai-Preiss and David O. Morgan, 37–67. Leiden: Brill, 1999.

- Morgan, David. Medieval Persia 1040–1797. London: Longman, 1988.

- Panofsky, Erwin. Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946.

- Rashid al-Din. The Successors of Genghis Khan. Translated by John Andrew Boyle. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.

- Robinson, Chase F. Islamic Historiography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Salomon, Frank. The Cord Keepers: Khipus and Cultural Life in a Peruvian Village. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Salomon, Frank, and George L. Urioste, eds. The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

- Sima Guang. Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government (Zizhi Tongjian). Translated by R.H. Mathews. 3 vols. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1956.

- Smith, Paul Jakov, and Richard von Glahn, eds. The Song-Yuan-Ming Transition in Chinese History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003.

- Southern, R.W. Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1970.

- Suger of Saint-Denis. The Deeds of Louis the Fat. Translated by Richard Cusimano and John Moorhead. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1992.

- Tatlock, J.S.P. The Legendary History of Britain: Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and Its Early Vernacular Versions. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1950.

- Tolmie, Jane. “The Anglicization of Arthur: The ‘Historia Regum Britanniae’ and the Twelfth-Century Myth of Britain.” Florilegium 15 (1998): 161–178.

- Wallace-Hadrill, J.M. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People: A Historical Commentary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- Wormald, Patrick. “Bede, the Bretwaldas and the Origins of the Gens Anglorum.” In Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society, edited by Patrick Wormald, Donald Bullough, and Roger Collins, 100–129. Oxford: Blackwell, 1983.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.