This three-hundred-year period was one of artistic vibrance and immense cultural influence.

By Dr. Amanda Herring

Assistant Professor of Art History

Loyola Marymount University

Introduction

In contrast to the earlier Classical period, art of the Hellenistic period (c. 323–31 B.C.E.) has not been universally revered in modern art history. Beginning with Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the eighteenth century and continuing into the twentieth century, scholars referred to the period as one of decline and decadence. Yet, this approximately three-hundred-year period was one of artistic vibrance and immense cultural influence. In the twenty-first century, this period is finally beginning to see a revision in its reputation. Art historians and archaeologists are now recognizing the diversity and significance of the art produced in an era defined by conquest and war, cultural imperialism, dramatic and expensive art and architecture, and the transmission of art and ideas across large areas.

The chapter is framed by the rise of two empires, that of Macedonia in the fourth century B.C.E. and that of Rome in the second and first centuries B.C.E. At the beginning of the fourth century, people who identified as Greek lived across the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea, and after the conquests of Alexander the Great and the establishment of Hellenistic kingdoms at the end of the century, Greek cities were established in Europe, north Africa, and Asia as far east as Bactria (modern Afghanistan). This chapter is organized primarily thematically, considering art and architecture within its original historical context.

The Hellenistic Kingdoms formed after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E. when most of the territory of his empire was split between his generals, who each established their own kingdoms. They stretched from the eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia.

Conquests of Philip and Alexander

After Philip II, king of Macedonia, came to power in 359 B.C.E., he began to expand his rule south into mainland Greece through a combination of diplomatic and military efforts. Ancient Macedonia, which occupied a territory in the northeastern Greek peninsula that today is divided primarily between the modern countries of Greece and North Macedonia, had a hereditary monarchy as its governmental system, contrasting to the city-states (poleis) of southern Greece.

There were cultural differences between the southern Greeks and Macedonians as well. Macedonian Greek was its own dialect, and the cultural institutions that surrounded their monarchy, with its associated societal hierarchy, set them apart.

Evidence of this cultural and political system can be seen in the lavishly decorated tombs filled with rich grave goods found at a number of sites in Macedonia, notably the royal burials at Vergina (ancient Aigai), as well as the monumental architecture built for the king and his court, such as the palace and other buildings at Pella with their impressive pebble mosaics.

After the Battle of Chaironeia in 338 (when Philip’s army defeated combined Athenian and Theban forces), Philip gained control of most of Greece. Philip placed himself as the leader of the newly formed League of Corinth, which included all of the Greek states except Sparta. The stated goal of the federation was to preserve peace among the Greek cities, but this was enforced by Macedonian dominance and military might. At its first meeting, the league ratified Philip’s plan to invade the Persian Empire in retaliation for the Persian Wars in the previous century.

Philip was assassinated in 336 and unable to complete his plans. They were instead taken on by his son, Alexander (the Great), who ascended to the throne at the age of 20 after his father’s unexpected death. Over the next thirteen years until his own death in 323, Alexander and his army embarked on a military campaign of conquest that established Alexander’s rule over a territory of approximately two million square miles. It stretched from Greece and Egypt in the west across Mesopotamia and Persia and into Central Asia and India.

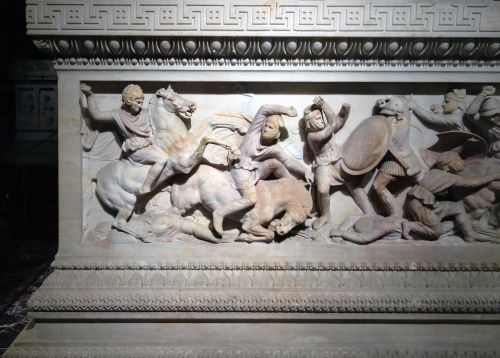

Alexander carefully cultivated his image as a god-like hero, founding cities he named after himself, and commissioning portraits. Alexander tightly controlled his imagery, allowing only one sculptor, Lysippos, and one painter, Apelles, to create portraits that depicted the king with distinct, idealized features as a young conqueror. While none of these original portraits have survived, the type was influential, shaping Greek portraiture for centuries. Alexander’s successors commissioned and displayed portraits of the king and ordered images of themselves that emulated those of Alexander in order to connect themselves with his glory. This was the case for one of the earliest surviving portraits of Alexander from the Alexander Sarcophagus, which most likely served as the burial place for a king of Sidon in Lebanon. He was a Phoenician king who owed his position to Alexander and commemorated this connection with Greek-style images of Greeks and Persians in battle or hunts on his sarcophagus.

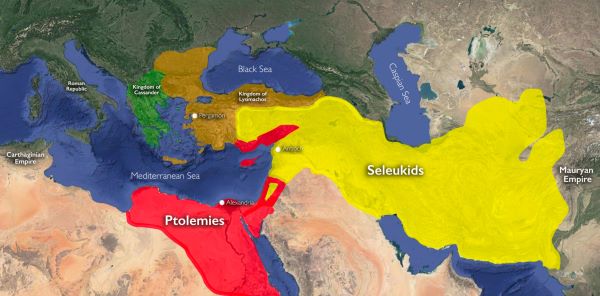

Hellenistic Art and Changing Ideas of Greek Identity

Alexander’s empire only lasted as long as he lived, and after his death most of his territory was split between his generals, who each established their own kingdoms. For the next three hundred years, the eastern Mediterranean and much of West Asia were dominated by these kingdoms. Three major centers of power emerged: Egypt under the Ptolemies, the parts of West Asia under the Seleukids, and Greece and Anatolia, which saw various rulers, notably the Attalids of Pergamon. As the kings fought for dominance, warfare was nearly constant and the borders of their kingdoms changed regularly. Large, cosmopolitan cities like Antioch, Alexandria, and Pergamon emerged with diverse populations and wealthy upper classes.

As part of their establishment and maintenance of power, most Hellenistic rulers practiced cultural imperialism, promoting Greek language, culture, and religion in territories that previously did not identify as Greek. The period is now known as the Hellenistic period due to this spread of Greek (Hellenic) culture. Yet, this was not simply the imposition of Greek culture across passive, conquered peoples. These kings ruled over millions of people of different ethnicities who spoke numerous languages and worshiped various gods. The cultures, religions, and art of the conquered people influenced those of the conquerors in turn.

There is a large variation in what we identify as Hellenistic art, across the Hellenistic world and across the three centuries that we identify as the Hellenistic period. Yet, the Hellenistic world was intensely interconnected, with artistic ideas, trade, and people moving across huge swaths of territory. There were common cultural touchstones that connected these different areas, notably the spread of the common Greek language, the worship of Greek gods, and Greek artistic style and iconography. Yet, these were regularly re-interpreted on a local level by different populations, and the formation of art and identity was a constant negotiation that happened primarily on a local level. An examination of the funerary complex at Nemrut Dağ of Antiochos I, a king of Kommagne in the first century B.C.E., who traced his lineage from both Greek and Persian kings, provides an example of Hellenistic hybridity.

Kommagene (Commagene) was a small kingdom located in southeastern Anatolia on the Euphrates River. For much of its history, it acted as a border state between the first the Hellenitic, then Roman empires and Parthia. Its rulers traced their lineage from Seleukid Greek and Persian kings, and the influence of Greece and Persia is visible in their art. Most of the population likely spoke a local dialect of Aramaic.

Hellenistic Sculpture: Power, Victory, and Drama

Aided by a more interconnected economic and political world, elites commissioned luxury goods like mosaics and metal wares that they displayed in their homes as signs of status. At the rulership level, art was used to advertise military victories, promote royal propaganda, and create new identities for their kingdoms and their people. Statues like the Nike of Samothrace were erected in panhellenic sanctuaries as statements of military power.

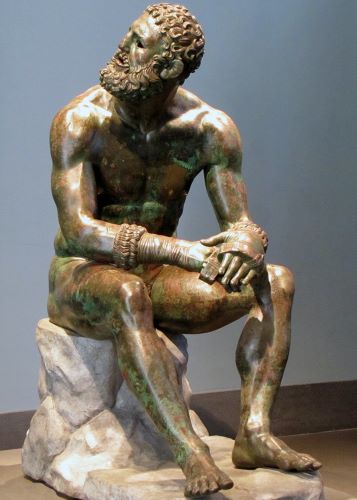

Reflecting the changing societies and cultures that emerged in the Hellenistic period, sculpture moved away from the idealism of the Classical period, embracing a wider variety of subjects and styles. Some Hellenistic statues, like the Nike of Samothrace, are dramatic and theatrical and require the viewer to engage with them physically by moving to different vantage points to view the artworks in their entirety.

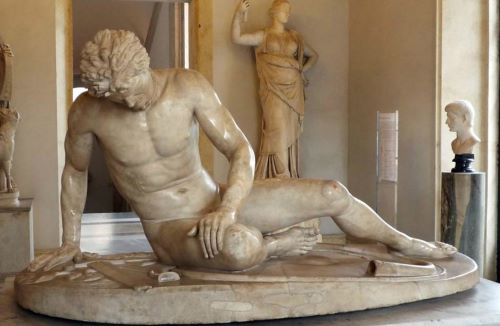

Others, like the Seated Boxer, embrace realism. The boxer depicts, not a young, idealized athlete, but a beaten, middle-aged man, reflecting changes in the role of athletics in Hellenistic society and the growth of professional athletes. Yet, the Seated Boxer could depict a different version of victory. This could be not an image of defeat, but rather the veteran boxer, who even when he looks defeated, can stand back up and win a bout in the ring.

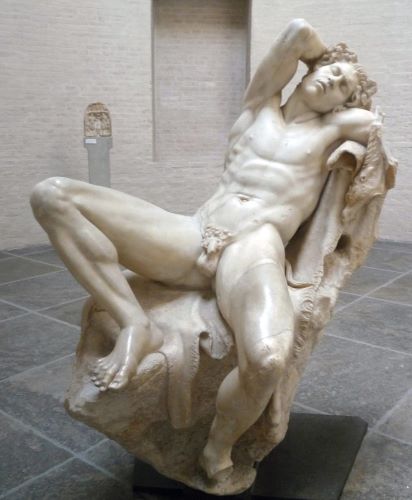

Other statues reflect on the contrast between power and vulnerability. Sleeping figures, like the Barberini Faun and the Eros Sleeping, became popular. The Eros statue shows the god, whose arrows of erotic love could fell even the most powerful god, as an adorable, sleeping toddler.

The Barberini Faun depicts the physically large and muscled form of a satyr, a part animal, part human creature, asleep and distinctly vulnerable. He is also overtly sexualized in a way that earlier male nudes, and even most Hellenistic male nudes, were not. This new depiction of the male form reflects changes in ideas of sexuality in the Hellenistic period. While sexual relationships between two men were common in the earlier periods (see earlier chapter), the roles that each lover played were strictly and socially defined, as the relationships were seen to benefit society. In the Hellenistic period, there were changes in how people saw themselves within society, and where they looked for happiness and identity. As citizens of large kingdoms, rather than small city-states, people were more connected to the rest of the world through trade and political networks, and those that lived in large, cosmopolitan cities regularly came into contact with people of different ethnicities and cultures. Yet, many felt disconnected from their distant monarchical rulers, and often did not feel a common identity with their closest neighbors. People now frequently looked to family and personal relationships for happiness and identity, rather than their place within a civic structure. Sexual relationships were seen as one way to pursue happiness, resulting in a subsequent relaxing in the strict definitions of sexual roles. The Barberini Faun is illustrative of this change, as a mature man could now be seen as an object of desire.

Pergamon

In Anatolia, the kingdom of Pergamon, like Athens in the fifth century, invested heavily in art and culture. Pergamon was a distinctly Hellenistic entity, emerging as a power in the early third century B.C.E. after the first king of Pergamon, Philetairos, broke away from Lysimachos, who had taken Anatolia after Alexander’s death. Philetairos took Lysimachos’s vast fortune with him, and he and his successors, the Attalids, used it to expand their kingdom until they controlled most of western Anatolia. They did this primarily through military conquest, and commissioned numerous monuments to celebrate these victories.

Philetairos was the founder of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon. He was a general in the army of Lysimachos, who placed Philetairos in charge of guarding his treasury in Pergamon. He defected from Lysimachos (but kept his money) and through political maneuvering, was able to set up his own kingdom. He was succeeded by his nephew Eumenes I.

One of these was a sculptural group erected in the Sanctuary of Athena in Pergamon that commemorated their victories against a group of people known today as the Gauls. The Gauls were a Celtic people who, beginning in the third century B.C.E., moved into mainland Greece and Anatolia, conducting raids on Greek cities and fighting a series of battles against various kings and cities. In their victory monuments, the Attalids followed the model of the fifth-century Athenian artworks that commemorating their victories against the Persians. The Attalids promoted their defeats of the Gauls as a triumph of a specifically Greek civilization over the non-Greek barbaric other.

Sculptural victory monuments over the Gauls were only one type of a number of monuments erected by the Attalids in their capital city of Pergamon. The Attalids built their new city, modeled architecturally on earlier Greek poleis, at a site that had previously been occupied by an Anatolian town. The Pergamenes were both Greek and Anatolian, and their cultural identity emphasized their descent from Greek heroes and connections to the mainland through shared history, as well as their shared past with other Anatolian cities. The highlight of this architectural program was the Pergamon Altar. The Altar, located in a prominent location on the acropolis in Pergamon, was lavishly decorated with sculpture, including a frieze depicting the battle of gods and giants (the gigantomachy) on the exterior and another that represented the life story of Pergamon’s most important hero, Telephos, on the interior.

The gigantomachy frieze is one of the largest surviving sculptural compositions to survive from the Greek world, originally depicting somewhere between 100 and 200 battling figures, and is now regarded as one of the great masterpieces of Hellenistic art. The gigantomachy was one of the most popular subjects in Greek architectural sculpture, and was regularly used as an allegory for the triumph of civilization over barbarism. On the altar, it likely commemorates Pergamene military victories, as well as celebrating Pergamon, its kings, citizens, and patron gods.

Rise of Rome

In a study of the art of the Hellenistic world, it is also necessary to examine a city outside of any of the Hellenistic kingdoms: Rome. Rome was first the capital of the Roman republic, and later, the capital of the Roman Empire. Beginning in the second century B.C.E., the Roman Republic began to expand its influence and power in the eastern Mediterranean, both through diplomatic and military methods. The Hellenistic kingdoms gradually fell to Rome and were incorporated into their territory. Egypt, under the rulership of Cleopatra, the final Ptolemaic king, was the last to be defeated by Rome in 31 B.C.E., marking the end of the dominance of the Hellenistic kingdoms.

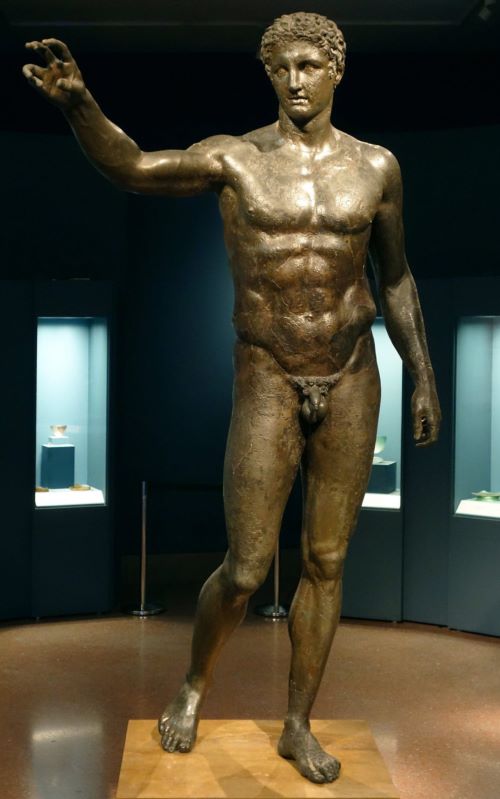

As Rome conquered Greek territories, they began to actively collect Greek artworks. Statues and other artworks were removed from temples and other public spaces and shipped across the sea to Italy where they were displayed in the homes of wealthy Romans. Some of the artworks never made it to Italy as they were lost at sea as the ships that carried them wrecked. Some of these wrecks, such as the Antikythera Shipwreck, have been recovered in the modern era, and their cargo preserved statues, such as bronzes, that have not commonly survived, and provided insight into the Roman artistic trade.

The Romans also enthusiastically copied famous Greek artworks, like the Doryphoros and the Aphrodite of Knidos, and many of the best-preserved examples of these statue types have been found in Roman contexts. Other Roman artworks used Greek artworks as inspiration, transforming the original into something new.

For example, the Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii was most likely based on a fourth-century Greek painting of a battle between Alexander and the Persian king Darius. Yet, the original subject was re-imagined as a tessellated mosaic that adorned the floor of a wealthy citizen in a small Italic town.

Greek artists, trained in Greek sculptural schools, also moved to Italy to work directly for Roman patrons, creating new statues in the Hellenistic style for distinctly Roman contexts. One such group of artists was Hagesandros, Athenodoros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, who in the first century created the statue of Laocoön and sculpture for the emperor Tiberius for his grotto at Sperlonga. The Laocoön, like many other Hellenistic artworks, requires their audience to engage with the statue emotionally, feeling pity while watching the Trojan priest scream his agony while he is bitten by snakes and watches his sons die.

For all of these Greek artworks, copies, emulations, and original creations, found in Italy, it is vital to consider their Roman context as well as their Greek style or creation. These artworks were transformed by their new locations and audiences. A statue that originally served as a votive dedication in a Greek sanctuary took on a new meaning when it adorned the garden of a Roman villa.

In the conquered Greek territories, Hellenistic art and culture endured under Roman rule, yet in modified ways. For example, in western Anatolia, Greek was maintained as the dominant language, Greek gods were still worshiped, and art in the Hellenistic style was still produced. Yet, the stamp of Roman rule was visible everywhere, including in declarations of political loyalty that were inscribed in sanctuaries and public squares as well as the images of Roman emperors placed on the obverses of coins. These cities are emblematic of the hybridized nature of the Hellenistic world. They are politically part of Rome, culturally Greek, and ethnically Greek and Anatolian.

The creation of new cultural, religious, and political identities, as well as new artistic forms to express these identities could be seen across the Hellenistic world. Art and architecture was produced by people of various ethnicities, languages, and religions who were conquered by Greek kings (and later Romans) and influenced by Greek cultural imperialism, yet also maintained aspects of their own native identities. This art is usually categorized as Greek, but it is much more than that, it is Hellenistic.

Originally published by Smarthistory, 08.25.2022, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.