Shakespeare depicts Brutus as torn between two opposed visions of heroism.

By Dr. Patrick Gray

Founding Director

Center for Arts and Letters

University of Austin

Introduction

In Julius Caesar, Brutus is a deeply attractive character, not only to his wife, Portia, and his friend, Cassius, but even to his murder victim, Caesar, as well as his chief rival, Antony. What makes Brutus so appealing, however, is a quality which he himself sees as a moral vice, empathy, including in this case a sense of civic duty. Despite his initial misgivings, Brutus backslides into political engagement: Cassius lures him away from Senecan philosophical isolation into an obsolescent Ciceronian enthusiasm for service to the state. Brutus’ kind-heartedness is political, as well as ethical, finding expression in a sense of noblesse oblige. He tries to withdraw from public affairs and ‘live unknown’ like an Epicurean philosopher, but he has too keen a sense of his responsibilities or what Cicero might call his officia (‘roles, obligations’) as a husband, friend and patriot; he cannot shake his old-fashioned pietas (‘duty, reverence’).

Even more striking, given his ostensible Stoicism, is Brutus’ tendency, like Coriolanus, to give way to compassion. Pity is an emotion which they both see, like Seneca, as an embarrassing and distracting weakness. As Russell Hillier observes, ‘The natural pity Martius finds within himself for his family and his people when he capitulates to the claims of “Great Nature” (5.3.33) shames him in the eyes of the Romans and the Volscians.’1 Like Coriolanus, Brutus finds to his chagrin that his strenuous efforts to maintain a sense of command over his inner life repeatedly break down. When he sees that he has hurt his friend, Cassius, or his wife, Portia, he yields, like a Christian, to a humane and generous desire to comfort them in their distress. This unbidden empathy, like his decision to engage in politics, is incompatible with his chosen ‘philosophy’ (4.3.143).2 His own ideal self is not the one which Antony describes, the Republican hero, animated by concern for the ‘common good’ (5.5.72), but instead the quasi-mythical figure of the Stoic sapiens, distinguished by his superhuman detachment from the world at large.

In sum, Shakespeare depicts Brutus as torn between two opposed visions of heroism: Stoic and proto-Christian. He aims to become an exemplary Stoic sage. But he fails to remain indifferent to the imminent collapse of the Roman Republic. He cannot bring himself to alienate his own wife, Portia, or his friend, Cassius. Instead, in his concern for other people, Brutus reveals an aspect of his character which cannot be reconciled to his ambition to be seen as a philosopher: a refractory streak of kindness. For Shakespeare, as well as his audience, shaped by the values of a Christian milieu, Brutus’ deep-set sense of empathy is attractive. It fits the Christian model of heroism: Christ’s self-sacrifice for love. For Brutus himself, however, acts of pity, including his own, are contemptible. His heroism, in so far as it is analogous to Christian heroism, is inadvertent, ‘accidental’ (4.3.144), rather than deliberate, emerging despite his own best efforts to restrain himself. Brutus’ reaction to his wife’s death, especially, stands out as a kind of felix culpa, redeeming him as a character from other-wise-insufferable Stoic posturing.

For a Stoic, love such as Christ’s is not a form of heroism, but a dangerous weakness. As Francis Bacon explains, ‘He that hath wife and children, hath given hostages to fortune.’3 When Brutus grieves for his wife, it humanises him in the eyes of the audience. To a Christian, tears can be noble; Christ himself weeps at the tomb of Lazarus. What Brutus wants, however, is instead to be what a Christian would call hard-hearted. As he sees himself, his concern for others’ well-being is not virtuous, but on the contrary an embarrassing, damning lapse in his effort to maintain, at all times, an appearance of Stoic constancy, if not that constancy in fact. Christian caritas has no place in that vision of an ideal self, the remote, self-sufficient philosopher exalted in Senecan Neostoicism. There is no room there for political activism; no room even for more discrete, personal acts of human fellow-feeling. Compassion by its very nature entails a loss of self-control: to empathise with others is to lose the emotional self-sovereignty which Seneca, especially, praises as the highest conceivable moral good.

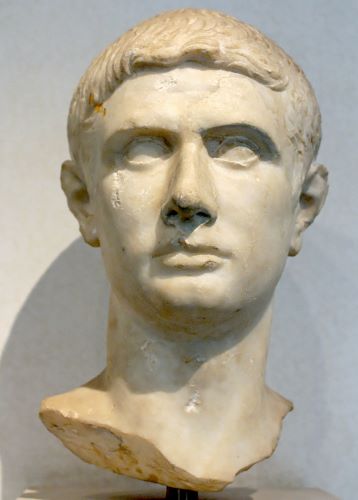

Shakespeare invokes older, more civic-minded Roman thought through the figure of Lucius Junius Brutus, Brutus’ ancestor, famous as the man who drove out the tyrannical Tarquins. This hero is a flesh-and-blood character drawn from history, or at least from quasi-historical legend. Within Stoic philosophy, however, the ideal self is often described in the abstract instead, simply as the sapiens (‘wise man’, ‘sage’). In Shakespeare’s tragedy, this figure appears as well, in a sense, in the form of a statue of the ancestor in question, Lucius Junius Brutus. Reflecting on Seneca in his Praise of Folly, Erasmus condemns his ideal sapiens as ‘a marble statue of a man, utterly unfeeling and quite impervious to all human emotion’.4 A statue is a vivid symbol of disinterestedness: a visual incarnation of Stoic apathia.

Brutus vs. Brutus: Seneca, Cicero and the Stoic Ideal

In this section, I begin by introducing the psychoanalytic concept of the ego ideal, and I argue in the spirit of Freud and Adler that this ideal tends to be articulated in images of the divine. The ideal self can also be hypostasised, however, as a fellow human being: a hero such a Christian saint. The ego ideal is contingent upon cultural context, as well as personal preference, and as such can be a Christian martyr, for example, or a Buddhist monk, just as easily as a warrior such as Achilles or Beowulf. Within Stoicism, the ego ideal is typically described in the abstract as the sapiens, a quasi-mythical ‘wise man’ or ‘sage’ who always does as he ought. Seneca sometimes identifies the figure of the sapiens with specific historical individuals such as Socrates and Cato the Younger. But that identification is pressurised, temporary and subject to doubt. In his essay ‘On Cruelty’, Montaigne turns against Seneca; after much thought, he concludes that Socrates and Cato did not in fact conform, as Seneca suggests, to the template of the Stoic sapiens. Even at their most heroic moments, the very instant of their suicides, they each felt some touch of exultation. ‘Witness the younger Cato,’ Montaigne writes. ‘I cannot believe that he merely maintained himself in the attitude that the rules of the Stoic sect ordained for him, sedate, without emotion, and impassible.’5

Despite himself, Shakespeare’s Brutus shows like signs of inner conflict: he describes himself as ‘with himself at war’ (1.2.46), ‘vexed’ with ‘passions of some difference’ (1.2.39–40). Brutus is not only torn, like Montaigne’s Cato, between his Stoic ‘attitude’ and his own emotions, but also between two rival moral imperatives. The tension between competing visions of ethics that Shakespeare’s Brutus experiences and that largely defines his character reflects the contrast between Seneca’s Epicureanism and Cicero’s Stoicism. For Seneca, apathia is an end unto itself, requiring disengagement from political obligations. Cicero, much to the contrary, denounces ‘philosophers’ who retire from the public sphere for ‘neglecting to defend others’ and ‘deserting’ their ‘duty’. ‘Hindered by their devotion to learning, they abandon those whom they ought to protect.’6

The Greek philosopher Xenophanes once quipped that, if animals were to describe the gods, they would draw pictures of themselves. ‘Horses would paint the forms of the gods like horses, and oxen like oxen.’7 Centuries later, Feuerbach came to much the same conclusion. ‘If God were an object to the bird, he would be a winged being.’8 In the nineteenth century a wide range of intellectuals, including Marx and Durkheim, as well as Fueurbach, came to see man’s gods as merely projections of himself. Man draws his own character upon an inanimate, indifferent cosmos. In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud is sympathetic to this tradition, but also introduces an important revision. Man is not so thoroughly self-satisfied as to imagine that God is simply identical to himself. Instead, concepts of the divine reflect a man’s concept of an ideal or perfect self, one to which he himself does not necessarily conform. God represents what Freud calls the ‘ego ideal’.

Long ago he [sc. ‘man’] formed an ideal conception of omnipotence and omniscience which he embodied in his gods. To these gods he attributed everything that seemed unattainable to his wishes, or that was forbidden to him. One may say, therefore, that these gods were cultural ideals.

Freud then defines more clearly what he means by ‘cultural ideals’: ‘what might be called man’s “ideals”’ are ‘his ideas of a possible perfection of individuals, or of peoples or of the whole of humanity, and the demands that he sets up on the basis of such ideas’.9

This understanding of the divine as an articulation of the character of the ideal self appears more clearly in the work of Freud’s contemporary rival Alfred Adler. Adler grants that ‘each person imagines his God differently’. Nevertheless, God is ‘the best conception gained so far of this ideal elevation of mankind’, ‘the concrete formulation of the goal of perfection’.10 For Adler, all of man’s activity can be explained in terms of a single master motive, comparable in character and explanatory force to Freud’s ‘libido’: a ‘striving for perfection’, ‘superiority’ or ‘overcoming’ which Adler sees as innate and integral to life itself:

Mastery of the environment appears to be inseparably connected with the concept of evolution. If this striving were not innate to the organism, no form of life could preserve itself. The goal of mastering the environment in a superior way, which one can call the striving for perfection, consequently also characterizes the development of man.

Adler takes some pains, however, to distinguish this urge from its most obvious apparent analogue, Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’. ‘Striving for perfection’ is not necessarily the same as ‘striving for power’.11

Unlike Nietzsche, Adler does not see an irreconcilable conflict between man’s ‘striving for perfection’ and his human feelings of compassion or pity: that ‘feeling with the whole’ which he calls ‘social interest’ (Gemeinschaftsgefühl, literally ‘community feeling’). Instead, he defines Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ as a subspecies of this ‘striving for perfection’, a misdirection of its energy away from man’s proper goal: the ‘common work’ of a ‘cooperating community’. ‘Deviations and failures of the human character – neurosis, psychosis, crime, drug addiction, etc. – are nothing but forms of expression and symptoms of the striving for superiority directed against fellowmanship (Mitmenschlichkeit, literally ‘being a fellow-man’, ‘co-humanity’).’ For Nietzsche, pity leads to décadence, a self-destructive malaise akin to the world-weariness Romantics called Weltschmerz (literally, ‘world-pain’). For Adler, however, precisely the reverse is true. To ‘concretise’ one’s ‘striving for perfection’ or ‘mastery of the environment’ as a ‘striving to master one’s fellow man’ is ‘erroneous, contradicting the concept of evolution’. The ambition ‘to dominate over others’ is the ‘incorrect path’, leading to the ‘decline and fall of the individual’, as well as the ‘extinction’ of entire ‘races, tribes, families’.12

What Adler calls ‘striving for perfection’ is not therefore sim-ply synonymous with what Nietzsche calls ‘the will to power’, and which Freud defines, in more sexual terms, as a longing for phallic potency. The ego ideal is open to a much wider variety of instantiations. If represented by a deity, that God need not be the wholly transcendent, impersonal God of classical philosophy. If represented by a human hero, the exemplum need not be a warrior such as Coriolanus. Depending upon a given individual’s or culture’s definition of ‘perfection’, the ideal self can at times be found instead in paragons of martyred passivity. It can be Jesus, for example, broken on the Cross. As Adler explains, ‘each person imagines his God differently’.13 In some cultures, it is not the warrior who inspires the most fervent admiration, but instead the martyr or ascetic. The idealisation of masculinity, physical force and invulnerability that defines Shakespeare’s Romans can be understood therefore as peculiar to their culture, rather than any kind of biological necessity or given of human nature. Their ego ideals, although compelling, are not the only such ideals possible. Moreover, in their aspirations, Shakespeare’s Romans are themselves not wholly internally consistent, either with each other or even within themselves, as individuals. They all seek power, in one sense or another, but power is subject to varying definitions. Caesar, for example, seeks political sovereignty: the power of a king. Brutus, however, wants to be able to control himself: the power of a philosopher.

Like all ethical systems, Stoicism presupposes a discrepancy between the real and the ideal. We are not what we could and should be, if we only recognised what it is we ought to do. Like all ethical systems, Stoicism then explains its exhortations by means of concrete examples, as well as abstract precepts. For Christians, for instance, the rule is the Golden Rule, and the exemplar is Christ. For Buddhists, the rule is the Eightfold Path, and the exemplar is the Buddha. For Stoics, the rule is Epictetus’ maxim ‘Bear and forebear’, or some variation thereon. The example, however, tends to be anonymous: the unnamed ‘wise man’ or ‘sage’ (Latin, sapiens). Like Hamlet’s Stoic friend, Horatio, the sapiens can therefore come across as a curious cipher: a mere blank space, albeit with praise attached.14 Typically, for instance, the ‘wise man’ is described apophatically, more notable for what he is not (‘passion’s slave’ [3.2.72]) than for what he is.15 Even so, the Stoics need him as a convenient shorthand. Even if he remains somewhat notional and indefinite, the ‘wise man’ as a placeholder crystallises their theorising into a personification. Seneca describes the sapiens as ‘calm’ and ‘unshaken’. He has ‘attained perfection’; his ‘mind’ is like ‘the superlunary world’, ‘always serene’.16

The figure of the Stoic sage also deflects possible charges of hypocrisy. By directing attention to people such as Cato and Socrates, Seneca need not present himself as a hero of his own moral system. ‘I hope someday to be a wise man,’ he explains, ‘but meanwhile I am not a wise man.’17 This modesty is a trope which he inherits from his Hellenistic Greek precursors, as he reveals in an anecdote about the Stoic philosopher Panaetius.

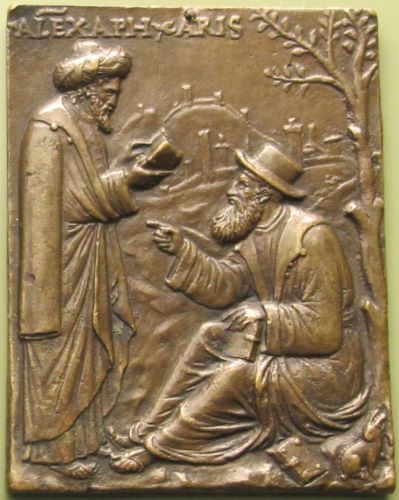

I think Panaetius gave a charming answer to the youth who asked whether the wise man would fall in love: ‘As to the wise man, we shall see. What concerns you and me, who are still a great distance from the wise man, is to ensure that we do not fall into a state of affairs which is disturbed, powerless, subservient to another, and worthless to oneself.’18

This habit of speech, however, gives rise to an obvious question. Is the ‘wise man’ wholly notional? In the course of human history, has any flesh-and-blood person ever fit this category? If not, could anyone ever even conceivably come to exist who might some-day, somewhere live up to its criteria? A living, breathing hero of apatheia? Alexander of Aphrodisias, a Hellenistic opponent of Stoicism, insists that ‘the majority of men are bad’. Nevertheless, he is willing to grant that ‘there have been just one or two good men, as their fables maintain, like some absurd and unnatural creature rarer than the Ethiopian phoenix’.19 More typically, Greek Stoic philosophers concede that the sapiens might not exist. Chrysippus confesses that ‘on account of their extreme magnitude and beauty we [Stoics] seem to be stating things which are like fictions and not in accordance with man and human nature’. And he admits, ‘Vice cannot be removed completely.’20 Epictetus also tries to temper expectation. ‘Is it possible to remain quite faultless? That is beyond our power . . . We must be content if we avoid [. . .] a few faults.’21 Cleanthes is the most optimistic of the Hellenistic Stoics, and even he gives little room for hope. ‘Man walks in wickedness all his life, or, at any rate, for the greater part of it. If he ever attains to virtue, it is late, and at the very sunset of his days.’22

With more confidence than his Greek sources, Seneca insists that it is possible for us to perfect ourselves, that is, to free ourselves from passion. Nevertheless, the feat is extremely unusual. ‘A good man’, ‘one of the first class’, ‘springs, perhaps, into existence, like the phoenix, only once in five hundred years’.23 ‘Perhaps’: even here Seneca hedges his bets. In his essay De constantia (‘On Constancy’), Seneca rebukes his friend, Serenus, for his doubts, but then trails off into careful qualifications of his claims.

There is no reason for you to say, Serenus, as your habit is, that this wise man of ours is nowhere to be found. He is not a fiction of us Stoics, a sort of phantom glory of human nature, nor is he a mere conception, the mighty semblance of a thing unreal, but we have shown him in the flesh just as we delineate him, and shall show him – though perchance not often; after a long lapse of years, only one. For greatness which transcends the limit of the ordinary and common type is produced but rarely.24

Seneca seizes upon two men above all as paragons of Stoic virtue: Socrates and Cato the Younger. And it is in response to Seneca that Montaigne returns to these two figures repeatedly in his Essays, testing the philosopher’s claims about their supposed apathia against his own more grounded sense of human nature.

Shakespeare casts a different character in the role of the possible sapiens: Brutus. Brutus combines, so to speak, the philosopher Socrates with the statesman Cato. Cicero, Seneca and Montaigne, for instance, all mention Brutus’ authorship of treatises on ethics, now lost.25 Cicero even dedicates two of his own philosophical treatises to Brutus, De finibus (‘On Moral Ends’) and Paradoxa stoicorum (‘On the Paradoxes of the Stoics’), citing him there as a friend, a Stoic, and an interlocutor in an ongoing, lifelong debate.26 Shakespeare shows his version of Brutus reading late into the night, just before the battle at Philippi, like Cato reading Plato’s Phaedo, just before his suicide, and gives him in his funeral oration the distinctive, staccato ‘Attic’ style associated with Stoic philosophy.

Throughout Julius Caesar, Shakespeare suggests that, if any-one in the play is Seneca’s ‘phoenix’, a hero of proto-Kantian disinterestedness, it is Brutus. In his eulogy at the end of the play, Antony exalts him as ‘the noblest Roman of them all’ (5.5.68). The Roman people, too, see him, at least at first, as a paragon of virtue. When Cassius tells Casca that he might join their party, Casca is delighted. ‘O he sits high in the people’s hearts,’ Casca crows. ‘That which would appear offence in us / His countenance, like richest alchemy, / Will change to virtue and worthiness’ (1.3.157–60). The conspirators trust that the Roman people will see Brutus’ intervention as an expression of his sense of civic duty, rather than, as in their own case, an outbreak of spite. As Antony observes,

All the conspirators save only he

5.5.69–72

Did that they did in envy of great Caesar.

He only, in a general honest thought

And common good to all, made one of them.

Antony admires his fallen enemy’s pietas: ‘a general honest thought’. For Brutus himself, however, this same patriotism is a troubling source of cognitive dissonance. The concern for the ‘common good’ which Antony praises as the best part of his character is incompatible with the Stoic ideal of indifference.

In his study of the concept of ‘constancy’ in Shakespeare’s Roman plays, Geoffrey Miles presents it as divided between a familiar definition as ‘steadfastness’, associated with Seneca, and a less familiar definition as ‘consistency’, connected with Cicero.27 In De officiis, Cicero exhorts private citizens to engage in public life, taking on and fulfilling their proper ‘offices’ or social roles for the good of the commonwealth, rather than remaining in more tranquil seclusion. Giles Monsarrat describes this sense of duty to the state as ‘a far cry from the self-sufficiency of the Stoic sage’.28 Nonetheless, Miles feels comfortable describing Cicero as a Stoic.29 Cicero does not simply disagree with Stoicism, he argues, but instead co-opts it, redefining its core ethical ideal of ‘constancy-to-oneself’ as ‘constancy-to-others’. Constancy becomes a ‘means to an end’ rather than an ‘end unto itself’. ‘Cicero’s ideal is a politician who has the moral qualities of a Stoic sapiens, but who uses them for the good of the commonwealth, rather than for his own self-perfection.’30

Miles is right to see a contrast between Cicero and Seneca, but their differences in this regard are not best explained, technically speaking, as manifestations of opposing interpretations of Stoicism. Marvin Vawter claims that ‘the Stoic Wise Man sees himself as an independent entity unwilling to bind himself to any specific community.’31 Miles agrees, as does Monsarrat. Cicero’s sense, however, that even philosophers should engage in politics is entirely in keeping with the Stoic doctrine known as oikeiōsis, a term which is not easy to translate; it means, literally, ‘the process of making things home’. Sometimes it is rendered as ‘appropriation’. According to this aspect of Stoic thought, which Cicero takes up in De officiis, the philosopher should extend his sense of himself outward in concentric circles, first to his family, then to his city, then to his nation; finally, to the entire human race, thinking of them as part of himself, so that his natural sense of individual self-preservation becomes instead a more expansive, impartial concern for every human being.32

The problem in this case is Seneca’s outsized influence on Neostoicism. Seeing him loom so large in the Renaissance imaginary, critics such as Vawter, Monsarrat and Miles whose focus is primarily Shakespeare and his contemporaries tend to mistake Seneca for a more general philosophical standard. But Seneca is not a reliable touchstone for classical Stoicism. Compared to his sources, Seneca is eclectic and idiosyncratic. His occasional exhortations to his friend, Lucilius, to abandon public affairs are not representative of main-stream Hellenistic or even Roman Stoicism, but instead of a rival school of thought: Epicureanism. Seneca’s recurrent praise for a private life of leisure and seclusion reflects the Epicurean precept, lathe biōsas (‘live unknown’).33 Seneca is not entirely consistent on this point; his essay De beneficiis (‘On Benefits’), in particular, explaining the importance of reciprocal gift-giving, can be understood, like Cicero’s De officiis, as an articulation and reimagination of the Hellenistic doctrine of oikeiōsis.34 More typically, however, Seneca advocates Epicurean self-sufficiency.35 The attraction of abandoning court life, fraught with anxiety and danger, for a more carefree, tranquil life of primitive isolation appears with great force, not only in his philosophical prose, but also in his tragedies, in the fantasies of protagonists such as Thyestes and Hippolytus.36

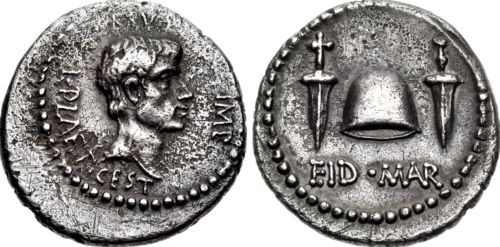

In Julius Caesar, Shakespeare illustrates the tension between Senecan Epicureanism and Ciceronian Stoicism in the contrast between the statue of Brutus’ ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, and the man himself whom that statue represents. Striving to persuade Brutus to join his conspiracy against Caesar, Cassius calls this illustrious forebear to mind.

O, you and I have heard our fathers say

1.2.157–60

There was a Brutus once that would have brooked

Th’eternal devil to keep his state in Rome

As easily as a king.

‘You and I have heard our fathers say . . .’: Cassius’ opening captures the importance to a Roman patrician such as Brutus of his sense of his place in a succession of noble patriarchs. As Sallust writes:

Quintus Maximus, Publius Scipio, and other eminent men of our country were in the habit of declaring that their hearts were set mightily afl ame from the pursuit of virtue whenever they gazed upon the masks of their ancestors . . . It is the memory of great deeds that kindles this flame, which cannot be quelled until they by their own prowess have equalled the fame and glory of their forefathers.37

Cassius’ final word, ‘king’, is also well chosen. As ‘Brutus once’ drove out the last ‘king’ of Rome, so now, he hopes, Brutus will help him forestall Caesar’s imminent coronation.

Up until this point, Brutus has been noticeably silent, still and cold, like a statue. He neglects his usual ‘shows of love’; his ‘look’ is ‘veiled’; Cassius complains that his ‘hand’ has become ‘stubborn and strange’ (1.2.34–7). Cassius must go to great lengths to spark even the slightest ‘show / Of fire’ (1.2.175–6). To help draw Brutus out of this retreat into himself, Cassius hits upon an unusual expedient.

Good Cinna, take this paper

1.3.142–6

And look you lay it in the praetor’s chair

Where Brutus may but find it. And throw this

In at this window. Set this up with wax

Upon old Brutus’ statue.

Fewer than twenty lines later, Shakespeare introduces a new character, as well, Lucius, a young male attendant. Like Macbeth’s valet, Seyton, or Antony’s, Eros, this minor character’s name is designed to reveal the more central protagonist’s inner psychomachia. Most immediately, ‘Lucius’ is derived from lux (Latin, ‘light’), and, appropriately enough, when he enters, Brutus asks him to fetch a taper. Lucius is also the praenomen, however, of ‘old Brutus’: Lucius Junius Brutus. It is significant, therefore, that it is this character, Lucius, who brings Brutus the first of Cassius’ letters. Unsigned, the letters are designed to appear like missives from the Roman people at large. In addition, however, they give voice to Brutus’ sense of his ancestor’s example: his likely exhortation, if he were present. Cassius brings ‘old Brutus’ statue’ back to life. ‘Speak, strike, redress!’ (2.1.47, 55)

Invoking this older model of heroism proves effective in unmooring Brutus from his Senecan withdrawal. His response echoes Cassius’ speeches earlier: ‘My ancestors did from the streets of Rome / The Tarquin drive, when he was called king’ (2.1.53–4). By luring Brutus into this Ciceronian mode of heroism, however, Cassius sets him at odds with himself. In his eulogy, Antony praises Brutus for his public-spirited engagement in politics, much in the spirit of Cicero’s De officiis. Brutus himself, however, might well balk at this description; he seems to want to come across, instead, as a model of Senecan disengagement. Even at the cost of alienating his own inner circle, as well as the Roman masses, Brutus aspires to be seen as a philosopher, rather than a statesman: a paragon of rational, unpreturbed detachment.

In their opening conversation, Cassius complains to Brutus that he seems cold and standoffish. ‘I am not gamesome’ (1.2.28), Brutus replies. ‘I do lack some part / Of that quick spirit that is in Antony’ (1.2.28–9). He strives to seem unmoved; much in contrast to Antony, he seems to pride himself on his own stillness and dissociation. Portia, too, complains that Brutus seems distant and devoid of affection. ‘Dwell I but in the suburbs / Of your good pleasure?’ (2.1.284–5). What humanises Brutus and renders him a sympathetic figure, a hero despite himself, is not so much his success at being a Stoic as his failure at his own set task. Unable to stick to his Stoic pride, Brutus gives way to compassion instead, prefiguring the very different moral world of Christianity.38 As A. D. Nuttall writes, ‘His love for his wife and his grief at her death, “affections” Brutus is proud to be able to repress, actually redeem him as a human being.’39

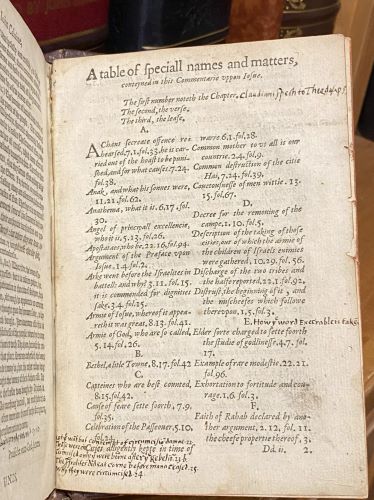

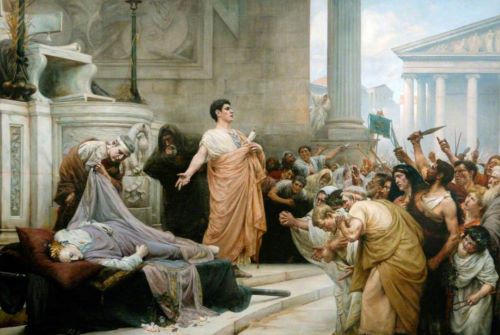

Under pressure, Brutus occasionally sets aside his performance of Stoic indifference, revealing emotions such as pity, grief and anger. Unfortunately, however, he is only willing to let down his guard in private. This concern for his public reputation as a philosopher is much of the reason why his funeral oration is not more successful. He is not willing to be passionate in public, as Antony is. Instead, he tries to sway his audience through arid, impersonal argument. ‘Censure me in your wisdom’ (3.2.16), he says, appealing to his fellow Romans’ faculty of reason. ‘Be patient till the last’ (3.2.12). Conceding nothing to what we now might call optics, pausing at no point for any tug at the proverbial heart-strings, Brutus presses hoi polloi with challenging counterfactuals and conditionals, in the manner of a present-day analytic philosopher. ‘Had you rather Caesar were living, and die all slaves, then that Caesar were dead, to live all free men?’ (3.2.22–4). ‘If . . . if then . . . this is my answer’: Brutus’ brusque, interlocking ‘if . . . then’ statements call to mind the characteristic sorites of Hellenistic Greek Stoics such as Zeno, Cleanthes and Chrysippus. ‘As he was ambitious, I slew him’ (3.2.26–7). In his dialogue De finibus (‘On Moral Ends’), Cicero, master orator, complains about the logic-chopping of the Stoics, gives an example and rejects it out of hand as hopelessly unpersuasive: ‘“Everything good is praiseworthy; everything praiseworthy is moral; therefore everything good is moral.’ What a rusty sword! Who would admit your first premise?’40

Antony wins the people’s hearts because Brutus, hindered by a peculiarly Stoic squeamishness, resolutely fails to pre-empt his rival’s more persuasive appeal to pathos. His insistence on his own dry logic baffles his audience, which fails to follow his intricate reasoning. Brutus’ carefully cultivated persona of disinterest and scrupulous objectivity comes across as unnatural, even repugnant, rather than reassuring. Antony’s tears, provocations and mingling with the crowd; his display of Caesar’s mangled, bloody cloak and corpse: these oratorical masterstrokes are left to fill an emotional vacuum. ‘I will myself into the pulpit first,’ Brutus assures Cassius, ‘and show the reason of our Caesar’s death’ (3.1.236–7). ‘The reason’: how far Brutus overestimates the power of such an appeal to reason soon becomes painfully clear, as the plebeians begin to respond to Antony’s emotional fireworks. ‘Methinks there is much reason in his sayings’ (3.2.109), one remarks. Brutus gets no such commendation. Setting aside questions of rhetorical technique, to permit Antony to speak at all, even to allow him to remain alive, is a grave tactical error, as Cassius recognises. ‘The people may be moved’ (3.1.234), he warns Brutus. ‘You know not what you do’ (3.1.232). Brutus, however, underestimates the power of emotions, including feelings such as loyalty or friendship, as well as romantic love.41

Not long after, as the Roman Republic collapses into open civil war, recrimination erupts between Brutus and Cassius. The two generals meet in Sardis after some time apart, and Cassius immediately accuses Brutus of betraying his trust. ‘Brutus, this sober form of yours hides wrongs’ (4.2.40). Brutus urges Cassius to speak ‘softly’, however, and retire to his tent, out of sight of their respective armies. ‘Before the eyes of both our armies here,’ he says, ‘let us not wrangle’ (4.2.43–5). Once he and Cassius are on their own, Cassius complains that Brutus ignored his request that Lucius Pella be pardoned, and Brutus accuses him in exchange of ‘an itching palm’ (4.3.10), selling ‘offices’ to ‘undeservers’ (4.3.11–12). Cassius responds with indignant protests, and the dispute degenerates into acrimonious grandstanding. Cassius threatens Brutus, and Brutus mocks him in return. ‘There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats: / For I am armed so strong in honesty / That they pass me by as the idle wind’ (4.3.66–8). He, Brutus, will not ‘tremble’, ‘budge’ or ‘crouch’ under Cassius’ ‘testy humour’ (4.3.44–6).

In De constantia, Seneca compares the Stoic sapiens to ‘certain cliffs’, which, ‘projecting into the deep, break the force of the sea, and, though lashed for countless ages, show no traces of its wrath’.42 Like these cliffs, or like Caesar, when he calls himself ‘Olympus’ (3.1.74), Brutus will not be moved. In his account of the ideal Stoic sage, Seneca explains in some detail how he reacts to others’ anger. He is unruffled, disdainful, serene, just as Brutus pretends to be here: ‘he either fails to notice them, or counts them worthy of a smile’.43 Cassius, however, is cut to the quick by this show of casual contempt. ‘Have you not love enough to bear with me?’ (4.3.118), he asks. Seeing that his friend is hurt, Brutus drops his frosty pretence. ‘When I spoke that,’ he confesses, ‘I was ill-tempered too’ (4.3.115). ‘Much enforced’, he admits he showed ‘a hasty spark’ (4.3.111). Put to the test, Brutus’ ‘love’ for his friend, Cassius, overrides his Stoicism.

In his essay ‘Of Books’, Montaigne cites Brutus’ private quarrelling with Cassius as a paradigmatic example of the discrepancy between a public persona and a private person. He begins by lamenting the loss of Brutus’ treatise on virtue, ‘for it is a fine thing to learn the theory from those who well know the practice’. Then he doubles back. ‘Theory’ does not always correspond to ‘practice’. ‘But since the preachings are one thing and the preacher another, I am as glad to see Brutus in Plutarch as in a book of his own.’ As in Shakespeare’s play, one episode in Brutus’ life stands out: ‘I would rather choose to know truly the conversation he held in his tent with some one of his intimate friends on the eve of a battle than the speech he made the next day to his army.’44 Montaigne likely has in mind here what would later serve as the classical source text for Shakespeare’s scene, a short passage in Plutarch’s biography of Brutus. ‘[Brutus and Cassius] went into a litle chamber together, and bad every man avoyde, and did shut the dores to them. Then they beganne to powr out their complaints one to another, and grew hot and lowed, earnestly accusing one another, and at length both fell a weeping.’45

It may well be the case that Shakespeare was influenced by Montaigne’s musing about Brutus in his tent: his quarrel scene seems designed to fulfil Montaigne’s wish. In this case, however, Montaigne’s spirit echoes Plutarch’s own. At the beginning of his biography of Alexander the Great, Plutarch distinguishes himself from more traditional historians. ‘My intent is not to write histories, but only lives. For, the noblest deedes doe not always shew mens vertues and vices, but oftentimes a light occasion, a word, or some sporte makes mens natural dispositions and maners appeare more plaine, than the famous battells wonne, wherein are slaine tenne thowsande men.’46 Seneca, too, stresses the need to examine philosophers’ lives for signs of hypocrisy. ‘Deed and word should be in accord.’47 Shakespeare departs from Plutarch’s simpler narrative, however, by suggesting not only that Brutus fails to maintain his composure in private, but also that he tries to cover up that lapse, in order to preserve a public image of himself as a dispassionate Stoic. In Shakespeare’s version, Brutus is much more consciously performing the role of a Stoic sapiens. He insists that he and Cassius speak inside his tent, for instance, out of earshot of their men.

Brutus’ investment in his own reputation as an exemplary Stoic sage is most obvious, however, after this scene, in his reaction to the message from one of his captains, Messala, that his wife, Portia, is dead. Reconciling with Cassius after their heated exchange, Brutus calls for a bowl of wine: a symbol of self-indulgence and momentary emotional liberty. The wine calls to mind, as well, Cassius’ initial accusation, outside Brutus’ tent: ‘Brutus, this sober form of yours hides wrongs’ (4.2.40). Brutus is not as ‘sober’ as he seems, literally as well as figuratively. ‘Wrongs’, moreover, takes on in retrospect an intriguing ambivalence. Cassius’ own meaning is that Brutus has wronged him as a friend; he has been unkind, unsympathetic. Brutus also ‘hides wrongs’, however, in a Stoic sense: he is more prone to emotional breakdown than he lets on. His studied persona of indifference is ‘form’, rather than ‘substance’. Cassius’ word ‘form’ aptly suggests at once both a detached and unrealised ideal, like a Platonic form, and a hollow shell: an exterior show or pretence, as opposed to an authentic interior lived experience.

Cassius for his part marvels that Brutus lost his temper; Brutus, a man who prides himself above all on his emotional self-control. ‘I did not think you could have been so angry’ (4.3.141). Brutus replies, ‘O Cassius, I am sick of many griefs’ (4.3.142). Cassius is surprised at this answer and chides Brutus gently, mostly in jest, for failing to abide by his Stoic principles. ‘Of your philosophy you make no use / If you give place to accidental evils’ (4.3.143–4). Brutus’ pride is stung by this remark, however, and he responds with a clarification, in the form of a slightly disturbing boast. ‘No man bears sorrow better. Portia is dead’ (4.3.145). Cassius is shocked: again, Brutus’ ‘sober form hides wrongs’ (4.2.40). From one perspective, that of a Stoic, Brutus is in the wrong to be troubled by Portia’s death. As he admits, he is ‘sick with many griefs’ (4.3.142). From another perspective, however, that of human compassion, Brutus is in the wrong not to let himself mourn for his wife’s death more fully and openly.

Brutus asks Cassius twice not to mention Portia’s death, as if afraid that if he does, he will not be able to contain his grief. ‘Speak no more of her’ (4.3.156), he says; and again, ‘No more, I pray you’ (4.3.164). Meanwhile, however, Messala and Titinius enter, bearing letters. Brutus presses Messala for news about Portia, and Messala tells him at last, reluctantly, that ‘she is dead, and by strange man-ner’ (4.3.187). Without giving any indication that this report is not the first time he has heard of her death, Brutus abruptly launches into a brief, startling and, again, self-aggrandising speech. ‘Why, farewell, Portia: we must die, Messala: / With meditating that she must die once / I have the patience to endure it now’ (4.3.188–90). Messala is awed by this display of Stoic virtue, and he heralds Brutus straightaway as a paragon of heroic indifference. ‘Even so great men great losses should endure’ (4.3.191). Cassius, however, knows better. ‘I have as much of this in art as you,’ he tells Brutus, cryptically, ‘But yet my nature could not bear it so’ (4.3.192–3). Like the audience, Cassius knows that Brutus is adopting a persona here. As T. S. Eliot says of Othello, he is ‘cheering himself up.’48 He is, in fact, deeply affected by Portia’s death; he can barely keep himself from breaking down altogether. In order to impress his officers, however, he keeps up appearances. He wants to be seen as Stoic sapiens, not as a loving husband.

Some critics have found the so-called ‘double announcement’ of Portia’s death so puzzling as to suggest some sort of mistake, either in the manuscript itself or in the printer’s shop.49 According to this account, two drafts of the announcement, an early and a late, were somehow both included in the only authoritative source for the play, the 1623 Folio. A detail in the second announcement, however, suggests that it was included in full awareness of the first. Messala tells Brutus that Portia died ‘by strange manner’, and Brutus does not ask him to explain what he means. It is difficult to believe that Shakespeare meant this passage to stand alone. To mention that Portia died ‘by strange manner’ but not explain what that manner was would be an uncharacteristic disservice to his audience. Brutus’ ostensible lack of curiosity here is not a printer’s accident, but forms part of Brutus’ own deliberate deception of his officers. It is a ruse, and a revealing one, designed to suggest an incredible, awe-inspiring apathia.

In contrast to Messala, the audience is supposed to see through Brutus’ set-piece speech. Shakespeare uses the double announcement of Portia’s death, apparent on stage only to Cassius, to show that the ‘form’ of the Stoic sage is at best a fiction: a persona which can be performed, like an actor’s role, but which cannot in fact be maintained at all times, in private life as well as in public. Shakespeare takes us backstage, so to speak, in order to allow us to see the incongruity between the performer and the performance. In Cassius’ terms, Shakespeare presents Stoicism as an ‘art’ beyond the scope of human ‘nature’. Behind the façade of the superhuman Stoic philosopher, Shakespeare allows us to glimpse a different, more complex, and more plausible character. In his grief for his wife, as well as his kindness towards his friend, Brutus falls short of his own stringent philosophical standard. At the same time, however, he becomes a much more attractive human being: a hero in a different sense. In his failure at his own set task, Shakespeare’s would-be paragon of Stoic indifference turns out to be instead an admirable example of Christian compassion.

In his Praise of Folly, Erasmus censures Seneca for ‘removing all emotion whatsoever from the wise man’.50 Seneca for his part denies that he is making any such claim: ‘I do not withdraw the wise man from the category of man, nor do I deny him the sense of pain as though he were a rock that has no feelings at all.’51 Some things do ‘buffet’ the wise man, Seneca admits, even though they do not ‘overthrow’ him: ‘bodily pain and infirmity’, ‘the loss of friends and children’ and ‘the ruin that befalls his country amid the flames of war’. ‘I do not deny that the wise man feels these things,’ he maintains. ‘The wise man does receive some wounds.’ Erasmus thus might seem to misinterpret Seneca. Seneca himself, however, is inconsistent. At the end of De constantia, Seneca insists that the wise man is not altogether impervious to injury. ‘We do not claim for him the hardness of stone or of steel.’52 Yet this claim is in fact precisely the boast that he does make at the beginning of the essay. ‘The wise man is not subject to any injury. It does not matter, therefore, how many darts are hurled against him, since none can pierce him. As the hardness of certain stones is impervious to steel, and adamant cannot be cut or hewn or ground [. . .] just so the spirit of the wise man is impregnable.’53 The inconsistency of Shakespeare’s Brutus corresponds to an inconsistency in Seneca’s representation of the ideal Stoic sage.

Seneca’s reversals regarding the sapiens show the need, if only in terms of conceptual clarity, of finding a more absolute representation of the Roman ethical ideal, one uncompromised by the vicissitudes of human nature. And it is just such an ideal that can be readily discerned in the concepts of the divine put forward by classical philosophers, including Seneca himself. For example, I began this section by citing the philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon. Much as Plato does later in his Republic, Xenophanes disparages the anthropomorphic deities popular among his contemporaries. Xenophanes is not an atheist, however, in the vein of Feuerbach. His aim, rather, is to replace the gods of the poets with a different figure: ‘One God, the greatest among gods and men, neither in form like unto mortals, nor in thought.’ God, ‘the motionless One’, is not subject to change. He ‘abides ever in the selfsame place, moving not at all; nor does it befit him to go about now hither, now thither’.54 Already in the thought of this pre-Socratic figure, it is possible to see an adumbration of Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, as well as the impersonal ‘World-Soul’ of the Stoics.

The idea that God or the gods are wholly impassible, even impersonal, is not limited to the Stoa, but can be found in all major schools of ancient philosophy, including Platonism, Aristotelianism and Epicureanism. Stoicism is simply the most radical, confident attempt to attain this ideal in its purity, as a human being.55 Impassibility becomes in Stoicism not merely a characteristic of the divine or of the soul after death but a primary aim in this life, as well as the next. It is a condition, moreover, which the Stoic sage is thought to attain, at least to some degree. Seneca adopts the Epicurean idea of the gods as plural and personal, but indifferent to human affairs, and describes the hypothetical Stoic sapiens in their likeness. ‘The wise man is next-door neighbor to the gods and like a god in all save his mortality.’56 Or again, ‘a good man differs from God in the element of time only; he is God’s pupil, his imitator, and true offspring.’ The true wise man can even surpass God. ‘In this you may outstrip God; he is exempt from enduring evil, while you are superior to it.’57

Shakespeare, however, does not share Seneca’s confidence in man’s ability to escape his own emotions. In the next chapter, ‘“The northern star”’, I present the ideal of impassibility that I have begun to outline here in more detail, both in its original incarnation in classical philosophy and again in its resurgence in sixteenth-century Neostoicism, where it tends to be presented as the virtue of ‘constancy’. Like many of his contemporaries, Shakespeare does not see this kind of ‘constancy’ as compatible with human nature. Caesar, for example, compares himself to ‘the northern star’: a symbol of aloof invulnerability, like the various statues scattered throughout the play. Roman attempts to emulate these kinds of ego ideals end in tragedy. Caesar is not in fact the godlike figure that he starts to think he is, just as Brutus proves not to be an unshakeable Stoic sage.

Shakespeare’s implicit, concrete criticism of the ideal of impassibility resembles the explicit, abstract concerns of contemporary theologians about the possibility of reconciling Stoicism with Christianity, as well as related disputes about the relative merits of each ethical system. In his emphasis on man’s susceptibility to passions, accidents and material wounds, as well as his consistent counter-idealisation of an ethos of compassion, Shakespeare sides with the claims of Christianity against those of Stoicism. In the next section of this chapter, ‘“A marble statue of a man”’, I look more closely at early modern debate about the role of ‘pity’, in particular, in Stoic ethics. In delineating Shakespeare’s place along a spectrum of contemporary opinion, the influential Neostoic humanist Justus Lipsius provides a useful point of contrast. The notoriously severe theologian Jean Calvin proves a surprisingly sympathetic point of comparison. Despite manifest sympathy for misguided characters such as Brutus, Caesar and others, Shakespeare is a partisan of a Christian ethos of compassion, over and against the Neostoicism that he brings to life in his representation of ancient Rome.

‘A Marble Statue of a Man’: Neostoicism and the Problem of Pity

Over the course of the last several decades, following an early article by John Anson on Julius Caesar and Neostoicism, critics have tended to agree that a central project of this Roman play is a critique of Neostoic exaltation of ‘constancy’.58 Marvin Spevack in his Cambridge edition describes it as ‘the major dramatic, psychological, social, and political ideal’ of the play.59 Coppélia Kahn describes Romanitas in Shakespeare as ‘ethically oriented’, and directs the reader to G. K. Hunter’s longer description of ‘a set of virtues . . . thought of as characterizing Roman civilization – soldierly, severe, self-controlled, self-disciplined’.60 Paul Cantor observes, ‘It is difficult to find one English word to cover the complex of austerity, pride, heroic virtue, and public service that constitutes Romanness in Shakespeare.’61 Nevertheless, certain terms do appear repeatedly, and especially one: ‘constancy’. Vivian Thomas writes, ‘The fundamental values which permeate the Roman plays are: service to the state, constancy, valor, friendship, love of family, and respect for the gods.’62 Robert Miola narrows the list to three: ‘constancy, honour, and pietas (the loving respect owed to family, country, and gods)’.63 I would collapse these even further: a Roman’s sense of ‘honour’, for Shakespeare, depends on his sense of his own ‘constancy’. Geoffrey Miles, especially, argues convincingly that constancy ‘for Shakespeare and his contemporaries’ represents ‘the quintessential Roman virtue’.64

As I explained in the previous section of this chapter, ‘Brutus vs. Brutus’, the ethical ideal of ‘constancy’ can conceivably be pressed into the service of pietas, as in Cicero’s De officiis. It can also come into conflict with that sense of duty, however, as in the case of Seneca’s revised version of Hellenistic Stoicism. Retirement from city to country, negotium (‘business’) to otium (‘leisure’), is more typically associated with Epicureanism. Nonetheless, Seneca sees withdrawal from public affairs as the shortest route to Stoic ‘constancy’, understood in this case as imperviousness to external influence.65 Cicero, by contrast, like Virgil, subordinates the Stoic ideal of constancy to an older Roman ideal of pietas: reverence for gods, ancestors and the Roman state. ‘Constancy’ for Cicero does not mean complete indifference or apathia, but instead self-sacrificing service to others. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.66 Such patriotism is familiar from legends such as that of Marcus Curtius in Livy’s History, as well as Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid.

In this section of the chapter, I outline a second such debate about constancy, one more specific to the Renaissance. Much as Cicero and Seneca tried to promote Hellenistic philosophy, a new and controversial import from Greece, within the very different, largely incompatible context of traditional Roman mores, so also Shakespeare’s contemporaries, Neostoics such as Lipsius and Du Vair, tried to introduce Stoicism, a resurgent, contested legacy of ancient Rome, into a pervasively Christian milieu. Can the idea that constancy is a virtue be reconciled to Christianity? If Jesus as he appears in the Gospels is understood as the paradigmatic ethical exemplum, and constancy is defined, as it is for Seneca, as primarily apathia, freedom from emotion, then any such reconciliation is impossible. Jesus weeps, grows angry, suffers, dies; the details of his life forestall any coherent redefinition of this central Christian figure as a latter-day Stoic sage.

I address a third and final debate about constancy: the extent to which it is synonymous with masculinity. Can women be constant? For Shakespeare’s Romans, the answer is, for the most part, no. As Hamlet says, ‘Frailty, thy name is woman’ (1.2.146). The Latin language itself suggests this perspective: virtus literally means ‘manliness’. For Shakespeare himself, however, like Montaigne, the question itself would be misguided. Inconstancy is not limited to women but instead a defining characteristic of human nature, male as well as female. As Benedick says at the end of Much Ado about Nothing, ‘man is a giddy thing, and this is my conclusion’ (5.4.106–7). Every man has in this sense a kind of ‘woman’ within: a feminine aspect of himself which is susceptible to emotions such as pity and grief. ‘What patch or bit of one’s personality is essential?’ Peter Holbrook asks. ‘Which of our many contradictory drives is truest? How can we speak of authenticity if, as Montaigne says, “there is as much difference between us and ourselves as there is between us and other people”?’67

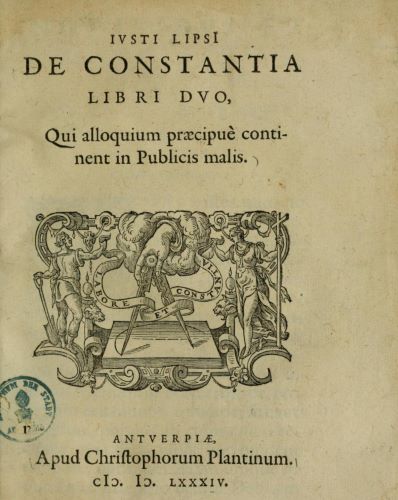

At present, however, I will focus on the opposition between Christianity and Neostoicism. The figure most immediately responsible for the revival of Stoicism in late sixteenth-century Europe is Justus Lipsius. His seminal work, De constantia, appeared in English translation in 1595, only a few years before the presumed composition of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in 1599. A shorter treatise by Guillaume du Vair, La Philosophie morale des stoïques (‘The Moral Philosophy of the Stoics’) ̧ based on Epictetus’ Manual, appeared in English only a year before, in 1598. Subsequent scholars such as Bishop Joseph Hall would build upon their ideas, and Stoicism would in time become a characteristic subject of later Jacobean drama.68 Given the early date of Julius Caesar, however, within the development of early modern English Neostoicism, it is not necessary at present to look beyond these two authors, into the seventeenth century. J. H. M. Salmon traces Neostoicism in England in this early period back to the influence, especially, of the Sidney circle. The Countess of Pembroke herself, for instance, translated a Neostoic treatise by Philippe de Mornay, his Excellent discours de la vie et de la mort (‘Excellent Discourse of Life and Death’), and published it in 1592 as part of a single volume with her translation of Garnier’s Marc-Antoine.

In his work on the Protestant concept of ‘conscience’, Geoffrey Aggeler draws attention to the curious fact that most of the English translators of Continental Neostoic treatises were not only part of the Sidney circle, but also, like Sidney himself, committed Calvinists.69 The conjunction might easily seem counter-intuitive. Drawing upon the final, most pessimistic writings of St Augustine, Calvin insists on man’s utter incapacity to control his own depraved nature. As a result of the Fall of Man, virtue is entirely dependent on God’s grace. Stoicism, by contrast, emphasises man’s ability to master his own emotions. Man in his strength is able to emulate and even exceed the divine, becoming self-sufficient through unaided, individual human effort. Reviewing the intellectual history of the Renaissance and Reformation, William Bouwsma takes up these two schools of thought as emblems of what he calls ‘the two faces of humanism’. ‘The two ideological poles between which Renaissance humanism oscillated may be roughly labeled “Stoicism” and “Augustinianism.”’70

At the end of his Apology for Raymond Sebond, in response to a lament of Seneca’s which he calls ‘absurd’, Montaigne draws a similar contrast. He cites Seneca: ‘O what a vile and abject thing is man, if he does not raise himself above humanity!’ ‘Man cannot raise himself above himself,’ Montaigne replies, except ‘by purely celestial means’. ‘It is for our Christian faith, not his [sc. Seneca’s] Stoical virtue, to aspire to that divine and miraculous metamorphosis.’71 Pierre de La Primaudaye, too, at the beginning of his popular French Academie, criticises the Stoics for not recognising man’s need for the grace. On the one hand, he maintains, we are to avoid the pessimism of ancient figures such as ‘Timon the Athenian’, who saw life as so miserable that he urged his countrymen to hang themselves. Man’s is not such ‘a vile and abiect estate’. On the other hand, however:

We must take heed, that we enter not into that presumptuous opinion of many others, who endeuour to lead man to the consideration of his dignitie and excellencie, as being endewed with infinite graces. For they persuade him, that through the quicknes of his vnderstanding, he may mount vp to the perfect knowledge of the greatest secrets of God and nature, and that by the only studie of philosophie, he may of himselfe, following his own nature become maister of all euill passions and perturbations, and attaine to a rare and supreme kind of vertue, which is void of those affections . . . Thus whilest they grant to mans power such an excellent and diuine disposition, they lift him vp in a vain presumption, in pride and trust in himselfe, and in his owne vertue, which in the end cannot be but the cause of his vtter undoing.72

At the beginning of Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, Berowne protests in like vein against the king’s proposal that he and his companions swear to forgo the company of women. ‘Necessity will make us all forsworn’ (1.1.147), he vows. ‘For every man with his affects is born / Not by might mastered, but by special grace’ (1.1.149–50).

The ‘special grace’ that Berowne invokes here, like the ‘special providence’ that Hamlet sees ‘in the fall of a sparrow’, is a technical concept borrowed from Calvinist theology. ‘Special’ in this context means ‘specific to an individual’ and tends to refer in Calvin’s Institutes to that ‘grace’ or ‘providence’ which God offers to each of the elect. Taken together, the two instances, Berowne’s ‘special grace’ and Hamlet’s ‘special providence’, suggest that in Shakespeare’s mind, as in the context Aggeler describes, Neostoicism and Calvinism stand connected. Hamlet’s comments about ‘special providence’ arise from his embrace of a fatalism which resembles that of a Roman Stoic. Alan Sinfield, for example, compares Hamlet’s speech to Horatio, ‘the readiness is all’, to Seneca’s essay, De providentia (‘On Providence’) as well as Calvin’s Institutes, as an example of the manifest difficulty in sorting out the two possible lines of influence.73

One explanation Aggeler offers for the connection between Calvinism and Neostoicism in Elizabethan England is that Calvin himself was much exercised to distinguish his interpretation of Christian theology from Senecan Stoicism, precisely because, as in the case of Hamlet’s determinism, the two could seem so eerily similar.74 English Calvinists then naturally took an interest in the pagan antagonist of the master. ‘Certainly his frequent references to Seneca and other pagan writers were noticed.’ Aggeler cites as an example the translator of Du Vair’s treatise on Stoic moral philosophy, Thomas James, who in his introduction defends his use of ‘words and sentences of the Heathen’ by appeal to Calvin’s authority.75

In his effort to distinguish between Stoicism and Christianity, Calvin insists in particular on the difference in their attitudes towards compassion for the weak and suffering. For example, Calvin’s first published book is a commentary on Seneca’s De clementia (‘On Mercy’), a treatise in which Seneca tries to convince his former pupil, the Emperor Nero, to be more merciful to his subjects. On the face of it, the exhortation might seem readily compatible with Christianity. Calvin, however, objects to the spirit in which it is made. Seneca does not appeal to Nero’s sense of sympathy, but instead to his sense of his own superiority. He wants to convince Nero, like Shakespeare’s Brutus, to take pride in seeing himself as an aloof and imperturbable sapiens, rather than in imposing sudden, cruel violence. ‘Cruel and inexorable anger is not seemly for a king, for thus he does not rise much above the other man, toward whose own level he descends by being angry at him.’ To bear a grudge is for ‘women’ or ‘wild beasts’, and ‘not even the noble sort of these’. ‘Elephants and lions pass by what they have stricken down; it is the ignoble beast that is relentless.’

For Christians, pity is the chief virtue. For Stoics, however, it is an inexcusable weakness. As Calvin explains in his commentary on Seneca, ‘Although it [pity] conforms, in appearance, to clemency, yet because it carries with it perturbation of mind, it fails to qualify as a virtue (according to the Stoics).’ As Calvin recognises, Seneca distinguishes carefully between misericordia (‘pity’), a vice, and clementia (‘mercy’), a virtue. Pity involves empathy with another person’s suffering, and thus a loss of emotional sovereignty: ‘the sorrow of the mind brought about by the distress of others’. Mercy, however, as Seneca describes it is a demonstration of power. The sapiens is charitable, pardons, gives alms; he does so, however, ‘with unruffled mind and a countenance under control’.76

Calvin finds this distinction unconvincing. ‘Obviously we ought to be persuaded of the fact that pity is a virtue, and that he who feels no pity cannot be a good man – whatever these idle sages discuss in their shady nooks.’77 The putative opposite of ‘pity’, a passionless ‘clemency’, is in his opinion a fiction, founded on a false notion of human nature. ‘To use Pliny’s words: “I know not whether they are sages, but they certainly are not men. For it is man’s nature to be affected by sorrow, to feel, yet to resist, and to accept comforting, not to go without it.”’78 In his later Commentary on Romans, Calvin cites St Augustine to similar effect. ‘As he [sc. St Paul] mentions the want of mercy as an evidence of human nature being depraved, Augustine, in arguing against the Stoics, concludes, that mercy is a Christian virtue.’79

In his Institutes,even as early as the 1539 Latin edition, Calvin complains about ‘new Stoics’ who, he says, ‘make patience into insensibility, and a valiant and constant man into a stock’.80 Calvin echoes here the work of an earlier humanist, Erasmus. In his 1529 edition of Seneca, Erasmus questions the authenticity of a supposed record of a correspondence between Seneca and St Paul, now recognised as a fourth-century forgery.81 In his 1511 The Praise of Folly, Erasmus lambastes Seneca’s ideal of the ‘wise man’ or sapiens. Like Calvin after him, Erasmus is put off in particular by Stoic disdain for pity. Folly asks, ‘Who would not flee in horror from such a man, as he would from a monster or a ghost – a man who is completely deaf to all human sentiment, who is untouched by emotion, no more moved by love or pity than “a chunk of flint or mountain crag” . . .?’82

Whereas Erasmus’ Folly speaks directly of Seneca, Calvin speaks somewhat more mysteriously of ‘new’ Stoics ‘among the Christians’. Who are these ‘new Stoics’ (novi Stoici)? Calvin does not identify them. Moreover, they predate standard narratives of the history of Neostoicism. Lipsius’ De constantia did not appear in Latin until 1584: almost fifty years later. Gilles Monsarrat suggests that Calvin is referring here to unspecified contemporary Christians, influenced by the resurgence of Stoic ideas in the sixteenth century. He has trouble identifying any positive instance of such Neostoicism earlier than 1542, however, some years after Calvin’s initial composition of the Institutes. Even then, the example that he does give, Gerolamo Cardano’s De consolatione, is not notably Christian; its author was later put in prison by the Inquisition for casting Jesus’ horoscope, as well as for writing a book in praise of the Emperor Nero, tormentor of Christian martyrs.83

Departing from Monsarrat, I would suggest that ‘new’ here may perhaps mean ‘new’ in relation to Seneca, rather than in relation to Calvin’s own early modern Europe. Pagan authors in late antiquity tend to criticise Seneca for infelicities of Latin style, as well as his compromising political entanglement with the reviled Nero. Marcia Colish details a countervailing tradition, however, of ‘Christian apologists and Church Fathers’, dating as far back as the second century, which ‘gave Seneca a new and more positive appreciation’. ‘These authors were less concerned with his biography and his literary style than with his moral philosophy, which they found strikingly compatible with Christian ethics at some points. They concentrated their attention on his ethical works, borrowing heavily from them and occasionally mention-ing him by name as a sage.’84 Tertullian, for example, refers to Seneca as Seneca saepe noster (‘Seneca, often ours’). St Jerome later drops the qualifier: Seneca for him is simply Seneca noster (‘our Seneca’).85

Calvin is more sceptical. ‘Now, among the Christians there are also new Stoics, who count it depraved not only to groan and weep but also to be sad and care-ridden.’ In his Institutes, as also in his commentary on Seneca’s De clementia, Calvin is especially appalled by Stoic disapproval of compassion. Appealing to the example of Christ, Calvin presents Stoic opposition to pity as an insurmountable barrier to any proposed reconciliation of Stoic and Christian ethics. ‘We have nothing to do with this iron philosophy which our Lord and Master has condemned not only by his word, but also by his example. For he groaned and wept both over his own and others’ misfortunes.’86 Calvin even provides an Old Testament type of this aspect of Christ in his Commentary on Genesis, in the person of Joseph. Having risen to preeminence in service to the Pharaoh, Joseph encounters after many years the brothers who betrayed him and sold him into slavery, and they fail to recognise him. He seizes the youngest, Benjamin, as his prisoner, having first framed him for a crime. Knowing his father’s love for the boy, one of the older brothers, Judah, offers to serve as a slave in his place instead. And, at this act of pity, Joseph cannot ‘restrain himself’. He orders everyone out of his chambers and begins to weep, then invites his brothers back in, reveals who he is, and provides for them in their poverty.

Calvin seizes upon one clause from this story, ‘Joseph could not restrain himself’, and expounds upon it with unusual vehemence. ‘Joseph had done violence to his feelings,’ he imagines, ‘as long as he presented to them an austere and harsh countenance.’ The image calls to mind Shakespeare’s Brutus, unable to hide his anxiety from Portia while the conspiracy is afoot; unable later, as well, to contain his anger at Cassius, once he learns that she has passed away. Influence, direct or indirect, is possible. An English edition of the commentary appeared in 1578.87 My more general point, however, is that Calvin and Shakespeare, as well as English Calvinists interested in Neostoicism, share a common interest in the tension between passion, especially pity, and a misleading appearance of stern, even cruel, impassivity. ‘At length,’ Calvin continues, ‘the strong fraternal affection, which he had suppressed during the time that he was breathing severe threatening, poured itself forth with more abundant force.’ This break-down, however, is not a vice, as Brutus sees it. Instead, Calvin argues, Joseph’s pity is laudable. ‘This softness or tenderness is more deserving of praise than if he had maintained an equable temper.’ On the whole, Calvin concludes, ‘the Stoics speak foolishly when they say, that it is a heroic virtue not to be touched with compassion. Had Joseph stood inflexible, who would not have pronounced him to be a stupid or iron-hearted man?’88

In Lipsius’ dialogue De constantia, ‘constancy’ is defined explicitly as the absence of any ‘passion’, including sympathy. ‘ “Constancy” is a right and immovable strength of the mind, neither lifted up nor pressed down with external or casual accidents.’ Writing during the Wars of Religion, Lipsius wanted to escape the turmoil around him, even if only subjectively, and thus welcomes Seneca’s Epicurean quietism. Patriotism, for him, is especially suspect. Lipsius’ interlocutor in the dialogue, ‘Langius’, complains that the word ‘piety’, a closer translation than usual, in this case, of the Latin term pietas, is sometimes used to mean ‘affection to our country’, rather than ‘honour and love toward God and our parents’. Even in this more limited sense, he maintains, pietas is a vice; a variation on ‘pity’, which he reproves, like Seneca, as by its very nature introducing a blameworthy, undesirable susceptibility to external turbulence. Langius attacks the central Christian virtue of compassion with startling directness. ‘Commiseration or pitying . . . must be despised by he who is wise and constant, whom nothing so much suits as steadiness and steadfastness of courage, which he cannot retain if he is cast down not only with his own mishaps, but also at other men’s.’ Lipsius’ persona in the dialogue, ‘Lipsius’, is shocked at the suggestion. ‘What Stoical subtleties are these?’ he asks. ‘Will you not have me to pity another man’s case? Surely it is a virtue among good men, and such as have any religion in them? . . . Are we so unkind and void of humanity that we would have no man to be moved at another’s misery?’89

The context of early modern Neostoicism is post-classical, Christian. Individual Neostoic authors, however, do not therefore inevitably aim at an explicit reconciliation of Stoic and Christian ethics. Lipsius’ degree of interest, in particular, in achieving such a synthesis, as well as Du Vair’s, can be easily overstated. As Monsarrat observes, Lipsius mentions God frequently in his De constantia, but the words ‘Christ’, ‘Christian’ or ‘Christianity’ do not appear at any point.90 His descriptions of God are drawn from classical sources such as Seneca, not the Bible.91 The same is true of Du Vair’s treatise, which, Du Vair himself attests, amounts to little more than a paraphrase of Epictetus’ Manual. ‘It is nothing els but the selfe same Manuell of Epictetus owne making, which I haue taken in peeces, and transposed according to that method and order which I haue thought most conuenient.’92 The disparity between Christian and Stoic ethics that Calvin emphasises, a difference of opinion about ‘pity’, is not addressed directly, but instead left unresolved.

The troubling pitilessness which figures so prominently in Calvin’s criticism of Stoicism, as well as Erasmus’, appears repeatedly in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The cold indifference to human fellow-feeling which Erasmus mocks and censures in his portrait of Seneca’s ideal sapiens Shakespeare sees as a characteristic problem of pagan Rome in general. Towards the end of Titus Andronicus, for instance, Lucius finds his father wandering the streets of Rome, pleading to the cobblestones for the life of his sons. ‘No man is by,’ Lucius protests. ‘You recount your sorrows to a stone’ (3.1.28–9). ‘They are better than the Tribunes,’ Titus replies. ‘When I do weep, they humbly at my feet / Receive my tears and seem to weep with me’ (3.1.38, 40–1). Roman authority, by contrast, is ‘more hard than stones’ (3.1.44).93

The opening scene of Julius Caesar proves in this sense a microcosm of what is to come. The problem of a characteristic Roman insensibility to the suffering of others is stated explicitly and almost immediately at the beginning of the play when the tribune Murellus rebukes the plebeians for celebrating Caesar’s victory over Pompey, a fellow Roman. ‘You blocks, you stones, you worse than senseless things! / You hard hearts, you cruel men of Rome, / Knew you not Pompey?’ (1.1.35–6). John Anson sees the callous embrace of cruelty Shakespeare’s Murellus describes here as the central problem of the play. ‘The body politic suffers a gradual loss of sensibility represented by the separation of hand from heart.’ Romans themselves become the victims of ‘a loss of compassion, an induration of feeling that gradually hardens their hearts’.94 The language itself, too, suggests that Neostoicism is in play. Murellus’ opening term of reproach, ‘blocks’, echoes Shakespeare’s Grumio’s pun about Stoics in his earlier Taming of the Shrew: ‘Let’s be no Stoics nor no stocks, I pray’ (1.1.31).95 Calling the Roman people ‘stones’ alludes, perhaps, to what Geoffrey Miles identifies as a recurrent conceit in Senecan Stoicism, the image of the sapiens as an impervious rock.96

Most clearly, however, Shakespeare’s language echoes that of Heinrich Bullinger in his third Decade. Bullinger took a strong interest in England’s conversion to Protestantism, keeping up correspondence with English Reformed clergy throughout his life; ministers fleeing the Marian persecution studied with him personally in Zurich and returned in 1558, after Queen Mary’s death, under the Elizabethan Settlement. Several became bishops. Parish preachers were required to read his sermons, and his Ten Decades were used at Oxford as a guide to ‘orthodox’ theology. Monsarrat gives details:

In 1586 Archbishop Whitgift ordered that ‘every minister having cure, and being under the degrees of master of arts, and batchelors of law’ should purchase the Decades, in Latin or in English, read one sermon every week and make notes; the second edition of 1584 was insufficient to meet the demand and a third appeared in 1587.97

Bullinger tends to follow Zwingli more closely than Calvin; in his criticism of what he calls ‘idle fellows’, however, ‘exercising themselves in contemplation rather than in working’, Bullinger hews closely to Calvin’s original. ‘Men must reject the unsavory opinion of the Stoics,’ he maintains, ‘touching which I will recite unto you, dearly beloved, a most excellent discourse of a doctor in the church of Christ’, that is, the passages on Stoic ethics from Calvin’s Institutes, which he repeats almost verbatim. ‘Upstart Stoics’, Bullinger laments, make ‘patience’ into ‘a kind of senselessness’, and ‘a valiant and constant man’ into ‘a senseless block, or a stone without passions’. The same language of ‘blocks’ and ‘stones’ reappears in another sermon from the same Decade, as well as Shakespeare’s Grumio’s ‘stocks’. ‘The Lord’, Bullinger says, would not ‘have us to be altogether benumbed, like blocks and stocks and senseless stones’.98

Throughout Julius Caesar, Shakespeare includes a wide variety of instances of coldness, insensitivity and other failures of human sympathy, ranging from the most extreme (murdering a friend) to the most quotidian (a passing social snub). In their opening conversation, Cassius accuses Brutus of being ‘too stubborn and too strange’, forgoing his former ‘gentleness’ and ‘show of love’ (1.2.34–8). ‘Y’have ungently, Brutus, / Stole from my bed’ (2.1.236–7), Portia complains. ‘And when I asked you what the matter was / You stared upon me with ungentle looks’ (2.1.240–1). Brutus kills a man whom he insists he also loves. ‘I . . . did love Caesar when I struck him’ (3.1.183), he tells Antony. To the crowd in the Forum he protests, as well, with an echo of Caesar’s characteristic illeism, ‘If there be any in this assembly, any dear friend of Caesar’s, to him I say, that Brutus’s love to Caesar was no less than his’ (3.2.18–20).

Brutus emphasises his love for Caesar in order to stress the supposedly disinterested nature of his political engagement. Ultimately, however, the ‘assembly’ of baffled plebeians find his emotional discipline alienating, instead. As Cassius and Portia speak of Brutus as ‘ungentle’, so also Antony censures him as ‘unkind’. Pointing out the place in Caesar’s cloak where, he says, ‘the well-belovèd Brutus stabbed’ (3.2.174), Antony describes him as having ‘unkindly knocked’ (3.2.177). ‘This was the most unkindest cut of all,’ he proclaims. ‘For Brutus, as you know, was Caesar’s angel. / Judge, O you gods, how dearly Caesar loved him’ (3.2.179–80). Antony then begins to speak of his ‘countrymen’, the gathered multitude, whom he describes as ‘kind souls’ (3.2.192). Weeping, like him, they feel ‘the dint of pity’ (3.2.193). ‘Dint’ recalls ‘knock’: Antony aligns the audience with the dead Caesar metaphorically, as if they, too, in their ‘pity’, had been physically affected by Brutus’ ‘most unkindest cut’.

In addition to the obvious, central event of the play, Caesar’s assassination, Shakespeare includes a number of instances in which Caesar and Brutus both alike refuse to be merciful. Just before he is killed, Caesar roundly refuses to pardon Metellus Cimber’s brother, Publius. In the quarrel scene, Brutus likewise dismisses Cassius’ pleas on behalf of Lucius Pella. In the Capitol, Brutus kneels before Caesar, interceding on Publius’ behalf, but fails even so to soften Caesar’s resolve. When the other conspirators press him, as well, for Publius’ pardon, Caesar points to this rejection: ‘Doth not Brutus bootless kneel?’ (3.1.75) Caesar seizes upon his resistance to his own known affection for Brutus as a symbol to the other petitioners of his ‘constancy’ to his own intentions, as if there could be no more striking proof of his imperviousness to their ‘prayers’ than his indifference to his ‘angel’ (3.1.59), Brutus. So, too, Brutus refuses to grant Portia’s entreaty, when she kneels before him and begs him, by ‘all’ his ‘vows of love’ (2.1.269), to tell her why he is ‘heavy’ with anxiety (2.1.274). ‘Kneel not, gentle Portia’ (2.1.277), Brutus replies. Portia, unsatisfied, strikes back with a play on the word ‘gentle’. ‘I should not need if you were gentle Brutus’ (2.1.278).

Brutus and Portia’s disputed term for each other here, ‘gen-tle’, appears repeatedly in Julius Caesar: ‘gentle Romans’, ‘gentle friends’ and so on.99 When Antony learns that Brutus is dead, he proclaims in his eulogy, ‘His life was gentle’, where ‘gentle’ seems to mean ‘noble’, aristocratic: ‘he was the noblest Roman of them all.’ Alone with Caesar’s corpse, however, Antony uses ‘gentle’ in a different sense: ‘Pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth / That I am meek and gentle with these butchers!’ (3.1.254–5). Referring to a series of examples ranging from 1555 to 1769, the OED explains that ‘gentle’ in Shakespeare’s time could mean a passive as well as an active quality; not just ‘considerate’ or ‘kind’, but also ‘flexible, yielding’: ‘Gentle a. 5: not harsh or irritating to the touch; soft, tender; yielding to pressure, pliant, supple. Obs.’ ‘Gentleness’ in this sense is the opposite of another key concept in the play, ‘constancy’, understood in contrast as rock-like intractability.

This concept of ‘gentle’ as ‘meek’, however, is under pressure from a competing definition of ‘gentle’ as ‘characteristic of the gentility’. In a world of tame courtiers, these two definitions would not necessarily contradict each other; an aristocrat would of necessity be skilled in the art of yielding. In Shakespeare’s Rome, however, these two concepts of what it means to be ‘gentle’ are irreconcilable, investing the term with pointed, dramatic irony. ‘Gentle friends, / Let’s kill him boldly, but not wrathfully; / Let’s carve him as a dish fit for the gods, / Not hew him as a carcass fit for hounds’ (2.1.171–4). The increasingly coarse, concrete language of the sentence, beginning with ‘gods’ and ending with ‘hounds’, moving from the elegance of ‘carve’ to the messiness of ‘hew’, progressively gives the lie to Brutus’ wishful, initial description of his co-conspirators as ‘gentle’.