Dance was thus one of many behaviours used in a constant renegotiation of where everyone stood in Roman society.

By Dr. Frederick G. Naerebout

Professor Emeritus of History

Universiteit Leiden

Rituals in their first, living existence are dynamic, always and everywhere.1 Unchanging traditions are a contradiction: if something manages to persist over longer stretches of time, it is because of its adaptability, the capability to change. Dance and other nonverbal components of ritual share in this dynamism. Nonverbal elements are often supposed to be relatively unchanging: the rituals develop, but nevertheless retain age-old movement patterns. This is a romantic notion disproved by the evidence: dance is as dynamic as any other element of ritual, if not more so, because of serious issues involved in how to ensure that the essence of a performance, by its very nature realized in the performance itself, is transferred across generations.2

So dance is a dynamic element of ritual, and this was also true in the Roman Empire. Although it was not the Roman Empire that introduced dynamism, it is likely to have had an impact on the nature of the dynamism, i.e. its direction, speed and intensity. This impact can be labelled with the problematic but probably ineradicable word ‘romanisation’, if by romanisation we understand the opening up of ever more avenues for the traffic of people, behaviours and mindsets, what one could call the ‘multiculturalism’ of the Empire.3 Within this context, rituals changed and were exchanged – with the concomitant music, song, dance and other nonverbal communication. In this paper we will focus almost exclusively on dancing. A detailed view on the phenomenon of dance in the Roman Empire contributes to our understanding of that society, the image of which will remain incomplete if one does not take into account its performances. At the same time, the story of the dance can illuminate or at least illustrate some of the mechanisms of acculturation at work in the Empire.

Is there still work to be done here? Definitely yes: dance in the Roman Empire has not had the attention it deserves. Let me state straightaway that I think dance was important in Rome – in a way difficult to grasp for those who live in modern western society, which so much privileges the verbal above the nonverbal, or the visual above the kinetic, and which tends to undervalue, or even suppress, the movement aspect in many of its own rituals. Most scholars, however, have been eager to point out the supposedly unmusical and non-dancing nature of the Romans. Remarkably eager, one has to say, as if they were glad to find at least someone in the ancient world who shared their own passive approach to such arts.4 Ancient Greece, the (equally false) image of which is presented as the opposite to Rome, has tended to monopolise the study of dance in the ancient world.5

Because the story of ancient Greek dance was carried forward to Byzantine days, or because ‘Greek dance‘ was treated as a timeless phenomenon, the Eastern part of the Empire has not been entirely neglected, but it is hardly ever addressed as belonging to the Romanworld.6 Indeed, whatever music and dance there was in the Roman world, it is supposed to be Greek – or degenerated Greek – and Etruscan.7 The popular (panto)mimic dancing in a theatrical setting obtained its share of scholarly attention, both its Hellenistic antecedents and its flowering all over the Empire, including the technitai, and other professional entertainers, as mentioned in inscriptions and papyri.8 But again, the craze for pantomime in Rome (and Constantinople) has hardly been discussed as a Roman phenomenon, rather as a foreign element introduced into Roman society. Some work has also been done on the Christian reaction to dance across the Empire. Christian authors discuss and condemn the dances of the heathen world, and Christian leaders are described as attempting to keep their flocks away from dancing and even from introducing dances into a Christian religious setting. This shows the popularity of non-theatrical dancing. But the Christian polemic against dancing is looked at in isolation and never enters into the discussion of Roman dance.9

It is obvious that our view of Roman dance is being obscured by a constant change of perspective: sometimes there is talk of Rome, at others of its Empire. Yet it is utterly artificial to consider the city of Rome separate from its growing Empire, and to put Rome in a category of its own (in this instance as having but poorly developed local dance traditions). That category does not exist, even if some Roman discourse would have it so (we will come back to this). We can hardly deny that the regions which are supposed to have been particularly keen on dancing as compared to Rome, such as Etruria and all of the Greek world, were, from a certain date onwards, ‘Roman’. We can see this mechanism of isolating Rome at work, for instance, when a comparative lack of ‘Roman’ sources is pointed out. The comparison is an unfair one: the Greek world with its countless city-states is compared with a single city-state, Rome, whose early history is notoriously undocumented. That there is something to tell about dance in the city of Rome at all, and that we even know about two sodalitates, the Salii and the fratres Arvales, whose rituals consisted partly in performing ceremonial dances, gives reason to think that dancing must have been quite prevalent in Rome in order to leave such traces in so meagre an overall record.10

If I am right, the notion that dance in Rome was a ‘foreign’ element, i.e. imported from the Greek world or Etruria, must be wrong, and dance in Rome had an ‘indigenous’ tradition as much as anywhere else. Of course it was enriched by influences from elsewhere – as almost everything ‘indigenous’ is. Influences will have come thick and fast, because Rome was building an Empire, and empires cause enhanced dynamism, as has already been explained above. What resulted from all this interaction was not foreign to Roman society, but very much part of Roman society – which in its several guises had always been the result of acculturative processes.

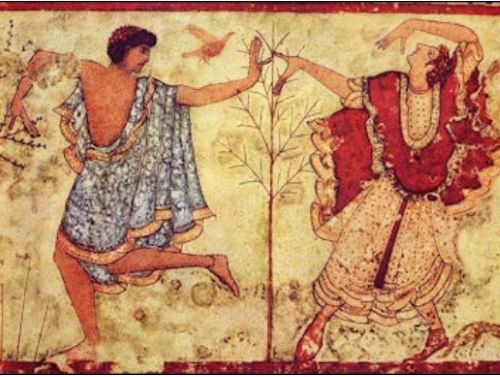

Rome became an Empire, and the Empire came to Rome. So we have to consider the full chronological and geographical extent of the Roman world when studying ‘Roman dance’.11 This means that we have a lot of evidence: many sources about dance in the Greek world (or sources in Greek about dance in the wider world) belong the Roman period. This also true for many images depicting the dance: Neo-Attic art, Campana reliefs, wall painting, statuary.12 Our view of what one could call the ‘dancescape’ of the Roman world will always be incomplete: the Empire was big, and there was an endless range of local repertoires. These local repertoires changed and were extended as time progressed. But there remains enough to tell: there was boundless variety in theatrical dancing in and out of the theatre; there was the Greek world with its civic ritual, within which dancing which had always been – and remained (but not without changes of course) – an important part of public events in Greek communities;13 there were public performances in a ritual context, whether limited to certain sanctuaries or of a more general nature, in non-Greek communities. But the complete „dancescape‟ cannot be fitted into this article and will have to wait for later studies.

When turning to the dynamism, the ‘impact of Empire’, we should go back first to the idea of a ‘danceless Rome’, where dancing supposedly was a Fremdkörper. What is the apparent appeal of this image? In part its appeal arises from a priori reasoning: Romans, it is claimed, were not the kind of people to waste their time on musical arts, as there were wars to fight and countries to conquer, which subsequently had to be provided with proper amenities. If there was to be any entertainment there were Greeks to provide it. Yet, surely the most important source for this image are the negative comments on dancing to be heard amongst the Romans themselves. These are so frequent that one cannot but conclude that Roman society – or at least the upper layers of that society – considered dance to be an essentially un-Roman behaviour. Who are we to contradict Roman opinion?

Indeed, we are not going to contradict it: we will let their opinion stand. We shall only re-read what the Roman authors said, in order to be a bit more precise. They considered some aspects of dancing to be an essentially un-Roman behaviour. Rome, amongst ancient societies, may not have been very different in the way dance was societally important, as has been argued above, but there was a well articulated Roman elite discourse on dance that distinguished quite strongly between proper and improper dancing.14 This does not show that Rome, actually or originally (whatever that may mean), was a society without dance. I think it shows above all the impact of Empire: the members of the elite turned dancing into one of the arenas where they tried to come to terms with the cultural dynamism of the Empire, and where ‘improper’ came to mean ‘un-Roman’ and vice-versa. They did this because dance was good to argue about within the sphere of cultural contest. Dance had a specific style – like speech, dress, food, music and song it was recognizable as ‘different’. Dance is an aspect of one’s identity: dancing ‘foreign’ dances means reshaping one’s identity. That happens easily enough: dance as nonverbal behaviour is contagious and thus ‘dangerous’. Talk about dance can be used as a kind of barometer, to see identities being shaped within the Roman Empire, not least the Roman identity itself. What kind of dancing was considered acceptable in what context in Rome and its provinces?

Cicero is always quoted to prove that Romans – or at least decent Romans – did not dance: nemo enim fere saltat sobrius, nisi forte insanit. But we have to look at the context of this statement: Cicero seeks the condemnation of certain elite individuals, for political reasons, and tries to blacken their reputation by pointing out their general lack of character and their disreputable behaviour – which includes dancing that probably (in his opinion) should be left to low-class professional performers (whereas the passive consumption of the dance is never explicitly rejected by Cicero).15 The only possible conclusion to be drawn from Cicero‟s words is that the Roman elite did dance. It may have been a mere stick to beat the dog when Cicero calls someone a dancer, but he expected such an argument to strike a chord with his audience. To this end the image of a dancing senator should not be an impossibility, but it also had to be the sort of thing that might be frowned upon. Apparently, it had to be a particular kind of dancing, one that was open to condemnation: Cicero repeatedly mentions nudity, and hints at ‘oriental’ music – but he is never very explicit. Was it all about a mismatch between dance, occasion, and/or performer?

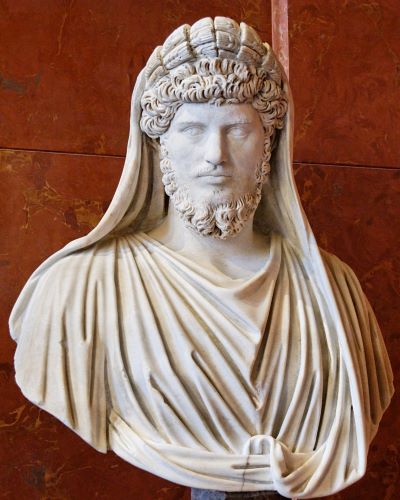

We will now look at the emperor Elagabalus (Heliogabalus) for a much later, but illuminating example for this phenomenon.16 It has been remarked of Elagabalus that “he made the round of the altars, performing sacred dances as he went”, without any comment, as if the author in question supposes that Roman emperors, or at least some of them, were wont to perform sacred dances.17 In the case of Elagabalus, however, we are supposed to understand it as something out of the ordinary: our sources seek to convince us that he was altogether an aberration, and one of the strategies employed to that end is representing the emperor and his entourage dancing. Our main source for this is Herodianus, who repeatedly mentions Elagabalus’ dancing in a cultic context, both in his native country and after he came to Rome.18 The ecstatic nature of this is underlined by the use of the word bakcheuein. Some passages in Herodianus seem to hint at the fact that the emperor could also be seen dancing in a non-cultic context, and this is stated more explicitly by Cassius Dio and in the Historia Augusta – who in turn do not refer to the cultic dance.19 Inserted into the narrative are some stories about Elagabalus favouring dancers and entrusting to them high offices of state.20 What can we make of this? Not too much, I would say, considering the nature of imperial biographies.

Still, it is not at all unlikely that this image of Elagabalus dancing around the altars of his god had a factual basis. Herodianus, our main source, perhaps came from Emesa and would certainly have known what he was talking about.21 More importantly, our sources leave us with the impression that in Syria cultic dancing was common: Elagabalus in his priestly role as the sacerdos amplissimus dei Invicti Solis Elagabali was performing dances that were an integral part of the cult of his god.22 Alas, we have no inscriptional evidence for the role of dancing within the cult of the god Elagabal, but there are several dedications to another god, Baal Marqod.23 Their main find-spot is at Der al-Qalat.24 Baal Marqod was the „Lord of the Dance‟, as can also be seen from the Greek equivalent koiranos kōmōn.25 The main literary source for Syrian cultic dancing, the 3rd-century author Heliodorus (a Syrian himself), deals with the god Melqart. “Phoenician sailors” from Tyros performed in an “Assyrian” (i.e. Syrian) manner in honour of this god:

I left them there at their piping and dancing, in which they frisked about at a tripping time provided by the pipes in an Assyrian measure, now jumping up lightly, now doing knee bends low to the ground, spinning their bodies round and round like possessed persons.26

This passage is often associated with a text from the Old Testament (1 Kings 18.21-26 and 19.18) describing the ‘limping’ priests of Baal.27 One may note that the Septuagint gives the Greek term oklazein in the passage on the Baal-priests, which is the word also used by Heliodorus (epoklazontes). We can thus suppose that the terms oklasma/oklazein were applied to dances in the Syrian tradition.28 It is, however, impossible to postulate a single continuing dance tradition, as is often done: there is the time span to consider, the issue of local variations, and the commonality of knee bends (plié).29

As to the nature of Elagabalus‘ dancing, we need not doubt that ecstatic dances were part of religious life in the area.30 Admittedly, the sources describing ecstatic dances refer to travelling groups of Galloi, and not to dances within the context of a temple – but this does not mean that such dances could not be ecstatic. There is some post-antique comparative material, and links backwards in time are found with equal ease in Egypt, ancient Israel and beyond.31 The techniques for provoking ecstasy are widespread, however, so there is no need to presuppose any direct links, and the gaps in time are rather too large for the parallels to demonstrate any form of continuity. Still, it is not too farfetched that Syrian cultic dances as performed by Elagabalus would have been of an ecstatic nature, although we really cannot say whether the descriptions given by Roman authors bear any relationship to the actual practices.

We should therefore ask what their image of Elagabalus dancing around the altars of his god can tell us, beyond the mere fact that this is what happened (and what I have just accepted as a fact). It certainly shows us that Elagabalus’ taking part in cultic dances did not go down well with the elite in Rome, where cultic dancing was not unknown, but of a rather different character compared with that of the Eastern half of the Empire.32 It entered into the hotchpotch of allegations, some with and some without a basis in real life, intended to ruin the emperor’s reputation. We do not find any attempt to understand what it was all about. From the perspective of the Roman Empire, however, there was nothing out of the ordinary in Elagabalus‟ dancing: it showed what a Syrian priest was wont to do, and something the Romans would look upon with some interest – possibly mingled with distaste, but interest nevertheless. But looking at this phenomenon from the perspective of Rome, our sources did not want to understand it, because it was very much out of place, so much so that distaste nullified interest.33

As Elagabalus’ reputation had to be blackened, he was shown as indulging in an un-Roman behaviour. Ecstatic dances from a Syrian tradition performed at the heart of Rome by the Roman emperor himself was about as un-Roman as things could get. On the other hand, the literary sources do not mention the cooptation of Elagabalus into the collegium of the fratres Arvales. The emperor‟s biographers probably were not aware of this fact, but it is likely that they would have avoided to mention it even if they knew it, as this was – in contrast to Syrian dancing – not an un-Roman behavior, but the right kind of dance, and thus the wrong kind of performance for their purpose.34 Whether an emperor ever performed with the Arvales or not, it would have been acceptable in principle.35 If however the dancing took place in a ‘foreign’ cultic context and was of an ecstatic nature, the ‘normal’ Roman inference would have been that the dancers were orientals, and thus Elagabalus could be characterized as an oriental by taking part in these cultic dances. This added to his the general image, borne out by his dress and other behaviour, which allowed it to present him as a clear example of the mos regius: he could be regarded as an oriental despot.36

So we can see dance being used as a way to characterise and denigrate an unwanted emperor. But not any kind of dance: traditional Roman dances would have had the opposite effect. Greek dance, with its mixed response within the Roman elite, would send out an ambiguous message.37 Syrian dance, however, had a suitably negative reputation: Syria was associated with wealth, luxury, degeneracy, servility, unreliability, craftiness, and cunning, and Syrian dance, associated (rightly or wrongly) with ecstatic behaviours and thus with loss of self-control, was considered as ‘indecent’.38 Such dancing was associated with libido, luxuria, impudentia, and impudicitia, as opposed to (Roman) decorum, duritia, gravitas, fides, pietas, auctoritas, moderatio, modestia, or virtus militaris. Despite a certain fascination, such dancing could easily be rejected by a Roman audience. The one moment you are in raptures watching the Ambubaiae, the Syrian dancing girls, at their stimulating performance. The next, you distance yourself (and your female kinsfolk) from these foreign performers, and call them prostitutes.39 Next, you pride yourself on being a member of a non-dancing race (meaning: “I am not a Syrian”).

Dance was thus one of many behaviours used in a constant renegotiation of where everyone stood in Roman society. As everyone in the Empire, Romans choose and Romans rejected certain cultural phenomena. There was more to choose from the more the Empire grew. A bigger Empire meant more displaced ritual, and more opportunities to use such ritual for one’s own ends, either by embracing or by criticizing it. The underlying idea of a political, social and cultural self-fashioning and self-representation is of course common.40 Dance has, however, not been explicitly introduced into this particular discourse. But dance belongs to it. In the Roman context those kinds of dancing that were performed by professionals and/or perceived as foreign could always be used to brand a certain person or group as lacking in common discipline and decency. I say “could be used”: where we speak of cultures accommodating to alien features we must realize that cultures or identities are dynamic – not only are they changing over time, but also from the one occasion to the next. According to Mary BEARD, the performance of the Galli within the cult of Magna Mater is “a (to us) paradoxical mixture of civic propriety, official patronage and wild, weird transgression; an assertion, at the same time of ‘Roman’ identity and its ‘Oriental‟ antitype’.41 A particular dance tradition could thus be type and antitype at the same time: obviously, it could serve to establish what was „Roman‟ and what was ‘Un-Roman’ at the same time. But we can also put in other types/antitypes: say, ‘Syrian’ or ‘Greek’.

I have been speaking about dance as a cultural marker. One could compare the way in which in a multicultural society filled with plenty of dance, i.e. Europe and America in the early 20th century, persistent voices were raised against the “dance craze” that was supposedly undermining the youth and thus the future of society. This denunciation was not aimed at dance in general, but at the so-called ‘negro dances’. Modern social dances thus came under attack as representing the unwelcome influence of primitive races –as opposed to the wholesome Greek culture, the product of “our race”.42 Of course we also find blanket condemnation of the dance, which originated in the ancient world with Christian leaders who threw all dance together to condemn it as immoral and inherently associated with pagan religious life.43 They made use of the Roman discourse on improper dance, but extended this to all dancing, thus negating the subtle differences brought into play by the Roman elite. This general rejection and prohibition of dancing was doomed to fail, because it was no longer part of ritual dynamism, as was Roman elite discourse, but sought to undercut it. That was, and is, suicidal.

Endnotes

- For the concept of ‘first/second existence’, see F. Hoerburger, ‘Once again: on the concept of ‘folk dance’, Journal of the International Folk Music Council 20 (1968), 30-32.

- F.G. Naerebout, ‘Moving events. Dance at public events in the ancient Greek world: thinking through its implications’, in: E. Stavrianopoulou (ed.), Ritual and Communication in the Graeco-Roman World (Liège 2006), 37-67.

- F.G. Naerebout, ‘Global Romans. Is globalisation a proper concept for understanding the Roman Empire?’, Talanta 38-39 (2008), 149-170.

- E.g. J. Landels, Music in Ancient Greece and Rome (London 1999), 172, speaking on “those not-so-very musical Romans” claims that “the role of music in Roman life and literature was very limited indeed compared to its all-pervading influence in Greek culture”. Landels’ index has an entry “dance, Greek”, but no entry “dance, Roman”. Cf. also F. Weege, Der Tanz in der Antike (Halle 1926), 147: “Zu der Fülle von Tanzarten und Darstellungen bei Griechen und Etruskern steht die Armut an solchen bei den Römern in scharfem Gegensatz … . Ethischen Wert [dem Tanz] gar beizulegen, wie die größten griechischen Philosophen es taten, wäre den Römern niemals in den Sinn gekommen, die viel zu nüchtern und trocken waren, um das wahre Wesen dieser Kunst zu verstehen”; C. Sachs, Eine Weltgeschichte des Tanzes (Berlin 1933), 166: “Die Geschichte des römischen Tanzes ist in der Tat mehr als arm”. For a struggle against such ideas, see B. Warnecke, in: Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft 2. Reihe, 4.2 (Stuttgart 1932), cols. 2233-2247, esp. 2245, s.v. “Tanzkunst”; A. Baudot, Musiciens romains de l’antiquité (Montreal 1973), 9-12; G. Fleischhauer, Etrurien und Rom. Musikgeschichte in Bildern 2.5 (Leipzig 1978), 5-7; and above all G. Wille, Musica Romana. Die Bedeutung der Musik im Leben der Römer (Amsterdam 1967), who explicitly rejects Sachs (on p. 178), and whose whole book can be considered as an extended polemic statement against those who think the Romans were not (so very) musical.

- Comparing E.K. Borthwick, ‘Dance II: Western Antiquity’, in: The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 5 (London 1980), 178-180, and R. Harmon, in: Der Neue Pauly 12.1 (Stuttgart 2002), cols.12-17, s.v. “Tanz” one recognizes the lack of scholarly progress in this field. Rome is all but absent, in spite of some work that shows the way on which one should move forward (cf. n. 4).

- Coverage is haphazard. I find it telling that H.H. Schmitt – E. Vogt (eds.), Lexikon des Hellenismus (Wiesbaden 2005), has no entry “dance” (and hardly any mention of the dance in other articles).

- L. Friedländer, Darstellungen aus der Sittengeschichte Roms 2 (Leipzig 1922, 10thed.), 163: “Eine römische Musik, insofern damit eine Kunst im höheren Sinne des Worts gemeint ist, hat es nie gegeben, sondern nur eine auf römischen Boden verpflanzte griechische”. Sachs 1933, op.cit. (n. 4), 167: “Rom ist einer Kunst unterjocht, die seinem inneren Wesen fremd ist und fremd bleibt”; ibid. 168: “Der Siegeszug dieser pantomimischen Kunst ist sehr bezeichnend. Die Römer, untänzerisch veranlagt und eingestellt, geben sich dem Genuss der darstellenden Tänze mit beispielloser Begeisterung hin. Tanz als Ekstase, als künstlerisch gebändigte Lebenssteigerung muss dem Nüchternen, Wirklichkeitssinnigen fremd bleiben; ihn fesselt nur derTanz, bei dem man sich etwas denken kann”. Borthwick 1980, op.cit. (n. 5), hardly mentions Rome, but suggests that in the imperial period dance in Rome was Greek dance in a degenerate phase, cf. S. Schroedter, in: Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Sachteil 9 (Kassel – Stuttgart 1998), 258-265, 258-259, s.v. “Tanz B. Antike II: antike griechische und römische Tanzkunst”: “Zweifellos mußte die Tanzkunst griechischer Provenienz in ihrer römischen Adaption erheblich an Bedeutung einbüßen. … [der Tanz] verlor nicht nur seinen ursprünglichen ganzheitlichen Charakter und ethisch-moralischen Anspruch, sondern auch an gesellschaftlichem Ansehen”. E.K. Borthwick, ‘Music and dance’, in: M. Grant – R. Kitzinger (eds.), Civilization of the Ancient Mediterranean 3 (New York 1988), 1505-1514 is more careful, but still contrasts Rome and Greece, and stresses the foreign fashions in Roman music and dance (p. 1511).

- Some recent titles: H. Leppin, Histrionen: Untersuchungen zur sozialen Stellung von Bühnenkünstlern im Westen des römischen Reiches zur Zeit der Republik und des Principats, Bonn 1992; id., ‘Tacitus und die Anfänge des kaiserzeitlichen Pantomimus’, Rheinisches Museum 139 (1996), 33-40; E.J. Jory, ‘The drama of the dance: prolegomena to the iconography of Imperial pantomime’, in: W.J. Slater (ed.), Roman Theater and Society (Ann Arbor 1996), 1-27; I. Lada-Richards, ‘Pantomime dancing and the figurative arts in imperial and late antiquity’, Arion 3rd series 12.2 (2004), 17-46; ead., Silent Eloquence: Lucian and Pantomimic Dancing (London 2007); E. Hall – R. Wyles (eds.), New Directions in Ancient Pantomime (Oxford 2008). For the relationship between the technitai and (panto)mime, S. Aneziri, Die Vereine der dionysischen Technitai im Kontext der hellenistischen Zeit (Stuttgart 2003), 207-211, 328-332; C. Roueché, Performers and Partisans at Aphrodisias in the Roman and Late Roman Periods (London 1993), 15-30. Cf. J.L. Lightfoot, ‘Nothing to do with the technitaiof Dionysos’, in: P. Easterling – E. Hall (eds.), Greek and Roman Actors. Aspects of an Ancient Profession (Cambridge 2002), 209-224.

- The most important exception is Ramsay MacMullen, who has consistently given attention to dancing in his studies of imperial and late antique religion (cf. R. MacMullen, Paganism in the Roman Empire [New Haven 1981]). C. Andresen, ‘Altchristliche Kritik am Tanz. Ein Ausschnitt aus dem Kampf der alten Kirche gegen heidnische Sitten’, Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 4. Folge 10 (1961), 217-262, remains fundamental. Recent studies on the subject include T.D. Barnes, ‘Christians and the theater’, in: Slater 1996, op.cit. (n. 8), 161-180, and G. Binder, ‘Pompa diaboli. Das Heidenspektakel und die Christenmoral’, in: G. Binder – B. Effe (eds.), Das antike Theater. Aspekte seiner Geschichte, Rezeption und Aktualität (Trier 1998), 115-147.

- Salii: CIL 6. 1977-1983 (Palatine); Arvales: J. Scheid, Commentarii fratrum Arvalium qui supersunt. Les copies épigraphiques des protocoles annuels de la confrérie arvale, 21 av.-304 ap. J.-C. (Rome 1998): 100a, 32; 101, 3 (tripodo), 100a, 38 (tripodatio), 100a, 32-35 (tripodaverunt). K. Giannotta, ‘Contents and forms of dance in Roman religion’, in: Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum II (Los Angeles 2004), 337-342, S. Estienne, ‘Saliens’, in: Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum V (Los Angeles 2005), 85-87, and J. Scheid, ‘Arvales’, in: ibid. 92-93, with full references. The idea that Roman elite rejection of the dance (to which we will come back below) is responsible for a reduced evidential basis, as expressed by M.-H. Garelli-François, ‘Le danseur dans la cité. Quelques remarques sur la danse à Rome’, Revue des Études Latines 73 (1995), 29-43, esp.29-30, is curiously flawed: any attack on dance that moves beyond the abstract is at the same time a source on the dance as practised. Garelli-François herself points out how Seneca, “paradoxalement”, shows how popular pantomime was in his days (p. 29).

- The account in Wille 1967, op.cit. (n. 4), 187-202 (§ 58: “Der Tanz im römi-schen Leben”; dancing in a theatrical context is dealt with in other paragraphs), with all texts quoted in extenso, is most valuable, but it does not cover the whole Empire.

- There exists no systematic collection of the imagery of dancers from the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

- E. Bowie, ‘Choral performances’, in: D. Konstan – S. Said (eds.), Greeks on Greekness. Viewing the Greek Past under the Roman Empire (Cambridge 2006), 61-92, argues that (competitive) choruses consisting of age groups were not common in the Roman era. A decline of citizen choruses, because of their replacement by professional performers, may have occurred, but material adduced by MacMullen 1981, op.cit. (n. 9), 185-186, n. 44-48, and id., Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries (New Haven 1997), 41, 102-106, 182 n. 28, provides evidence for long-term continuities. For continuity in the Hellenistic age, see F.G. Naerebout, ‘The Baker dancer and other Hellenistic statuettes of dancers. Illustrating the use of imagery in the study of ancient Greek dance’, Imago musicae. International Yearbook of Musical Iconography 18/19 (2001/02), 59-83, and id., ‘Quelle contribution l‟épigraphie grecque apporte-t-elle à l’étude de la danse antique?’, in: Colloque musiques, rythmes et danses dans l’Antiquité (Brest). Increasing theatricality, however, will have gone hand in hand with professionalisation, as argued persuasively by A. Chaniotis, ‘Theatricality beyond the theater. Staging public life in the Hellenistic world’, Pallas 47 (1997), 219-259, esp. 247-248.

- By far the best account of this discourse is Garelli-François 1995, op.cit. (n. 10). But I cannot agree with her that the answer lies in a polarity of ‘serious’ and ‘parodic’ dance forms: the issue seems rather more complicated. ‘Empire’ does not enter into Garelli-François’ account at all. As to the criticism of dance, I do not want to argue that it was exclusively Roman. That the supposedly dance-loving Greek world had its own way of criticising dance is often overlooked: in Homer manliness and bravery can be contrasted with proficiency in the dance; Herodotus gives us the story about Hippokleides dancing away his marriage (Herodotos 6.129), Plato argues for the inadmissibility of certain kinds of dancing, and in the Lucianic dialogue Peri Orchēseōs one Kraton, who has to be convinced of the moral and intellectual propriety of the pantomime, voices objections that must have sounded familiar in order to merit refutation.

- Cicero, Pro Murena 13; In Pisonem 22; 36; In Catilinam 2.23; In Verrem 2.3.23. Cf. Varro in Servius, Commentarius in Vergilii Bucolica, Ecloga 5.73 (religious dancing is mos maiorum); Macrobius, Saturnalia 3.14.4-7: even senators’ sons went to dancing schools, because dance was an honest undertaking. Honourable women may also dance, but not with an indecent amount of skill, taking up Sallustius, Catilina 25 (on Sempronia). Something I cannot go into here is the issue of different levels of exposure to the public gaze: exposure can be humiliating, and performing implies exposure. But not every performance implies the same level or kind of exposure.

- The following remarks are partly based on an unpublished paper given at Christ Church Oxford in the context of the Studia Variana coordinated by Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado.

- G.H. Halsberghe, The Cult of Sol Invictus (Leiden 1972), 84.

- Herodianus 5.3.8; 5.5.9; 5.6.1; 5.6.10; 5.7.4; 5.7.6; 5.8.1; Cassius Dio 79 (80).11.

- Historia Augusta, Antoninus Heliogabalus 32.8: Ipse cantavit, saltavit, ad tibias dixit, tuba cecinit, pandurizavit, organo modulatus est: “One could see him singing, dancing, reciting to the flute, blowing the trumpet, and playing the pandura or the organ” (following Turcan‟s translation: “on le vit…”, because of the theatrical context of 32.7). Cassius Dio 79 (80).14, remarks that Varius danced “not only in the orchestra but more or less also while walking, performing sacrifice, greeting friends or making speeches”. Whether he also performed in public in any non-cultic setting cannot be established, but I deem it a mere topos. The cultic dancing, however, is both topos and reality, as will be argued below.

- Historia Augusta, Antoninus Heliogabalus 12.1: As praefectus praetorio he installed a dancer who had performed in Rome (probably Publius Valerius Comazon Eutychianus[?], a freedman: PIR V 42. Apparently not a mere dancer: he had helped in the overthrow of Macrinus and later received the consular insignia and in 220 AD was Elagabalus’ colleague in the consulship. He was also prefect of the city on three different occasions). Cf. Cassius Dio 79 (80).4, and 77 (78). on Theocritus who “was of servile origin and had been brought up in the orchestra … . He advanced to such power in the household of Antoninus that both the prefects were as nothing compared to him”.

- M. Sommer, ‘Elagabal. Wege zur Konstruktion eines “schlechten’ Kaisers’, Scripta Classica Israelica 23 (2004), 95-110 claims that Herodian was a Greek who distanced himself from his Syrian surroundings (see p. 98-99 n. 29: “In sein Gegenteil wenden läßt sich Alföldys Argument, Herodian könne, seiner antiorientalistisch-antisyrischen Tendenz wegen nicht aus Antiochia stammen. Identität braucht Alterität; kulturelle Ressentiments sitzen … dort am tiefsten, wo heterogene Gruppen am dichtesten zusammenleben”) and did not really grasp what it was all about. In my view, Herodian had a very good understanding of what he talked about, and thus could put it to use, even to distance himself from it.

- J. Starcky, ‘Stèle d’Elahagabal’, Mélanges de l’Université Saint-Joseph 49 (1975/76), 503-520. Cf. R. Ziegler, ‘Der Burgberg von Anazarbos in Kilikien und der Kult des Elagabal in den Jahren 218 bis 222 n. Chr.,’ Chiron 34 (2004), 59-85, esp. 67-70. R.Krumeich, ‘Der Kaiser als syrischer Priester. Zur Repräsentation Elagabals als sacerdos dei Solis Elagabali’, Boreas 23/24 (2000/01), 107-112, on the iconography of Elagabalus as Syrian priest (especially the carrying of a twig or branch).

- Baal Marqod: three Greek (Balmarkodes) and fifteen Latin (Balmarcodus) inscriptions at Der al-Qalat (Qal’at, Gal’a), at the monastery of Beit Mery (Meri), to the northeast of Beyrouth. J. Teixidor, Bulletin d’Épigraphie Semitique (1972), no. 53; C. Clermont-Ganneau, ‘Le temple de Baal Marcod à Deir el-Kala’a’, Recueil d’Archéologie Orientale 1 (1888), 101-114; F. Millar, The Roman Near-East, 31 BC-AD 337 (Cambridge/MA – London 1993), 281. IGRR 3.1081 (= OGIS 2.589): [Κς]πίωι [Γ]ε[ν]/ναίωιΒαλ/μαπκῶδι / ηῶικαὶΜη/γπὶνκαηὰ / κέλεςζιν / θεοῦἈ/πεμθηι/νοῦΜά/ξιμορεὐσαπιζη/ῶνἀνέθηκα. IGRR 3.1078 (= CIG 4536): Μ. ὈκηάοςϊορἽλαπο[ρ] εὐξάμενορἀνέθηκαὑπὲπζωηηπίαρ / Κ[—]οςΕὐηύσοςρκαὶηέκνων. / Εἴλαθιμοι, Βαλμαπκώρ (-κώθ?), κοίπανεκώμων, / καὶκλύε [μ]ος, δέζποη[α], νῦνἹλάπος. / Σοὶμέλοιγὰπ [—]πωνἀνέθηκα / [η]ηλ όθενἐκνήζοιοῬόδοςηέσναζμαποθινόν, / Ἄμμωνορκεπαοῦσάλκεονἀνηίηςπον, / [εἰρὑγίην], πποσέονηαβπόηοιρἱεπόδπομονὕδωπ. IGRR 3.1079: I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo) B(almarcodi)… θεῶιἁγίωιΒαλ(μαπκῶδι). Cf. IGRR 3.1082: θεῶιΒαλμαπκῶδι.

- According to Teixidor 1972, op.cit. (n. 23), the remains at Der al-Qalat are of a rustic chapel. In fact it was a fairly substantial 1st century AD Roman podium temple, 32.88 meters in length, with a tetrastyle pronaos, 9.20 meters in length, and 17.10 meters in width (Clermont-Ganneau 1888, op.cit. [n. 23], 101-114). Cf. D. Krencker – W. Zschietzschmann, Römische Tempel in Syrien 1 (Berlin 1938), 1-3, and B. Servais-Soyez, ‘La ‘triade’ phénicienne aux époques hellénistique et romaine’, Studia Phoenicia 4 (1986), 347-360, esp.352.

- A.D. Kilmer, ‘Music and dance in ancient Western Asia’, in: J.M. Sasson (ed.), Civilizations of the Ancient Near East 4 (New York 1995), 2601-2613, for the Akkadian raqādu = to skip, to dance; raqqidu = a (cult) dancer; riqittu, riqdu = the dance. Koiranos kōmōn: see n. 23.

- Heliodorus, Aithiopika 4.17.1. Cf. C. Bonnet, Melqart. Cultes et mythes de l’Héraclès tyrien en Méditerranée (Leuven 1988), 67-68.

- R. de Vaux, ‘Les prophètes de Baal sur le Mont Carmel’, in: id., Bible et Orient (Paris 1967), 485-497, esp.487-490, connects mount Carmel (with a temple of Baal = Melqart), where Vespasian sacrificed (Tacitus, Historiae 2.78.3), with the Old Testament text from 1 Kings (see above), with Heliodorus (see n. 26), with C. Virolleaud, La légende phénicienne de Danel (Paris 1936), 189 (i.e. an inscription from Ras Shamra mentioning mrqdm = dancers), with Heliogabalus, with Baal Marqod, and with the tradition of Dea Syria as found in Apuleius, Lucian, and Florus. The thesis of De Vaux is repeated by A. Caquot, ‘Les danses sacrées en Israël et à l‟entour’, in: D. Bernot (ed.), Les danses sacrées (Paris 1963), 119-143, esp.128 ff. J.D. Seger, ‘Limping about the altar’, Eretz Israel 23 (1992), 120-127, links the texts collected by De Vaux to the imagery of a Mitannian seal of about 1500-1200 BC from Tel Halif and a terracotta from Tel Dan (cf. A. Biran, ‘The dancer and other finds from Tel Dan’, Israel Exploration Journal 36 [1986], 3-4). The horned headgear of the dancers would indicate Baal, and they are shown with bent knees in a limping or hopping dance. Seger is careful, not to say hesitant – but still, the basic idea is the unchanging nature of dance traditions. Cf. J. Teixidor, The Pagan God. Popular Religion in the Greco-Roman Near East (Princeton 1977), 58, and Bonnet 1988, op.cit. (n. 26), 68.

- Oklasma was a dance with squatting postures, already in use during the classical period (if the identification of certain imagery with the oklasma is correct) and associated with the East: see F.G. Naerebout, Attractive Performances. Ancient Greek Dance: Three Preliminary Studies (Amsterdam 1997), 223.

- Cf. Y. Garfinkel, Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture, Austin 2003.

- Lucian, Asinus 37; De Dea Syria 50-51; Apuleius, Metamorphoses 8.28; Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.23.13 (on Baalbek in the 5th c. AD). See also L. Robert, La déesse de Hiérapolis-Castabala, Cilicie (Istanbul 1964), on the fire walking and ecstatic dancing at Kastabala.

- See Bernot 1963, op.cit. (n. 27); Kilmer 1995, op.cit. (n. 25); A. Sendrey, Musik in Alt-Israel, Leipzig 1970; Near Eastern Archaeology 66.3 (September 2003), a special issue on ‘Dance in the ancient world’; Garfinkel 2003, op.cit. (n. 29).

- Cf. C.R. Whittaker in the Loeb edition of Herodianus 2 (1970), 41 n. 4: “Elagabalus’ real fault lay in making no concession to Roman tradition when introducing the local Syrian cult”. I think it might be safer to say: “not enough concessions”. As M. Pietrzykowski, ‘Die Religionspolitik des Kaisers Elagabal’, in: Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II 16.3 (Berlin 1986), 1806-1825, has stressed (on p. 1820), the ritual introduced to Rome can hardly have been shocking, as if nothing like it had been seen before: Rome had by that time a long tradition of all kinds of ‘foreign’ religious manifestations. Cf. M. Frey, Untersuchungen zur Religion und zur Religionspolitik des Kaisers Elagabal (Stuttgart 1989),105: traditional circles in Rome were at first prepared to tolerate this emperor and his god; only after two and a half years Elagabalus started to concentrate on a policy that was no longer acceptable. Note that modern authors have reacted as negatively to ‘oriental religion’ as the Romans: T. Optendrenk, Die Religionspolitik des Kaisers Elagabal im Spiegel der Historia Augusta (Bonn 1968), 6, quotes several examples.

- The cult of Elagabal was taken up in other poleis in the East: Ziegler 2004, op.cit. (n. 22), 74, 79 (following Robert 1964, op.cit. [n. 30], 79-82); for the West, see C. Bruun, ‘Kaiser Elagabal und ein neues Zeugnis für den Kult des Sonnengottes Elagabalus in Italien’, Tyche 12 (1997), 1-5. The short rule and damnatio memoriaeof Elagabalus probably accounts for the limirations of the evidence. Cf. also the paper by M. Icks, in this volume.

- Scheid 1998, op.cit. (n. 10), no 100b, 21-25 and J. Henzen (ed.), Acta fratrum Arvalium quae supersunt (Berlin 1874), 206. Pietrzykowski 1986, op.cit. (n. 32), 1815, wants to play this down, and remarks: “Dies waren nur wenige Gesten in Richtung der römischen Tradition”. But this seems unwarranted; cf. the coins showing the emperor sacrificing according to the ritus Romanus, as togatus and capite velato.

- Surely, emperors could dance: Ammianus mentions that emperor Julian was taught the pyrrhic dance (16.5.10).

- But the question remains: how much of this is pure Black Legend, how much is actual oriental religion misunderstood or misrepresented by contemporaries, or even orientalism propagated by the orientals themselves? The problem is neatly summarized by Millar 1993, op.cit. (n. 23), 308: “there was no single meaning” – according to circumstances certain features were accented: in Rome these are ‘Syrian’ or ‘Phoenician’. Sommer 2004, op.cit. (n. 21), contrasts Dio (using traditional Tyrannentopik in portraying Elagabalus as the mad pervert; note that G. Mader, ‘History as carnaval, or method and madness in the Vita Heliogabali’, Classical Antiquity 24 [2005], 131-172, esp.165, sees the image of the ‘Roman pervert’, with ‘Saturnalian’ chaos replacing outlandish ritual, mostly present in the Historia Augusta, not in Dio) with Herodian, who uses religion as a “cultural marker” to portray Elagabalus as the Other, the foreign element. Emesa is the background which allows him to paint the picture of a religious fanatic.

- Greek civic ritual attracted the attention of a Roman audience who even developed a historical and ethnographical interest in the matter (take Pausanias), and looked upon such dances as on a par with Roman (invented) tradition, such as that of the Salii. The attitude towards pantomime of Greek origin is more equivocal: M. Vesterinen, ‘Reading Lucian’s Peri orcheseos: attitudes and approaches to pantomime’, in: L. Pietilä-Castrén – M. Vesterinen (eds.), Grapta Poikila I. Papers and Monographs of the Finnish Institute at Athens 8 (Helsinki 2003), 35-51. Cf. n. 8 for further titles on the theatre.

- B. Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton 2004), 336-337. Cassius Dio 77 (78).6; 77 (78).10: Caracalla‟s bad traits were inherited from his Syrian mother. Cf. Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander 28.7: quia eum pudebat Syrum dici. On the other hand it is ambiguous who would actually count as a ‘Syrian’: it could be an autochthonous inhabitant of Syria, a Greek living in Syria, an inhabitant of the province of Syria, somebody with a father or mother of Syrian extraction. For a Greek – or one aspiring to be one – it might have been important to distinguish himself from Syrians by being and speaking Greek; but how to make sure of not beeing too Greek in Roman eyes? See S. Goldhill, Who Needs Greek? Contests in the Cultural History of Hellenism (Cambridge 2002), 75.

- The Ambubaiae shared with the Gaditanae the opprobrium of being prostitutes: A.T. Fear, ‘The dancing girls of Cadiz,’ Greece & Rome 38 (1991), 75-79 (reprinted in: I. McAuslan – P. Walcot (eds.), Women in Antiquity [Oxford 1996], 177-181), with all relevant texts, mostly from Martial. Cf. C. Edwards, ‘Unspeakable professions: public performance and prostitution in ancient Rome’, in: J.P. Hallett – M.B. Skinner (eds.), Roman sexualities (Princeton 1997), 66-95.My point is not that they were no prostitutes; they may well have been. But to condemn them as bad girls made them not a bit less popular: Schol. Iuv. 11: id est, speras forsitan, quod incipiant saltare delicatae ac pulchrae puellae Syriae, quoniam de Syris en Afris Gades condita est. For the relevant topoisee R. Höschele, ‘Dirty dancing. A note on Automedon AP 5.129′, Mnemosyne 59 (2006), 592-595.

- As in the work of Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Tim Whitmarsh, Greg Woolf and Simon Goldhill.

- M. Beard, ‘Vita inscripta’, in: La biographie antique (Genève 1997), 83-118, esp. 83. Cf. L. Roller, ‘The ideology of the eunuch priest’, Gender and History 9 (1997), 542-559, esp. 549: when identified with his homeland the eunuch is an exotic, non-threatening figure; when active in Rome he is an outsider whose gender and sexual status were viewed with alarmed disgust.

- In the words of Isadora Duncan, the prophet of modern dance, but not all modern dance; see F.G. Naerebout, ‘A detachment of beetles in search of a dead rat. The reception of ancient Greek dance in late nineteenth-century Europe and America’, in: F. McIntosh (ed.), The Ancient Dancer in the Modern World (Oxford, forthcoming).

- Cf. n. 9.

Contribution (143-158) from Ritual Dynamics and Religious Change in the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Eighth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Heidelberg, July 5-7, 2007), edited by Olivier Hekster, Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner, and Christian Witschel (Brill, 09.30.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.