The majority of the Oak Ridge inhabitants and workers were women.

By Alyssa Moore

Graduate Student of Archives and Public History

New York University

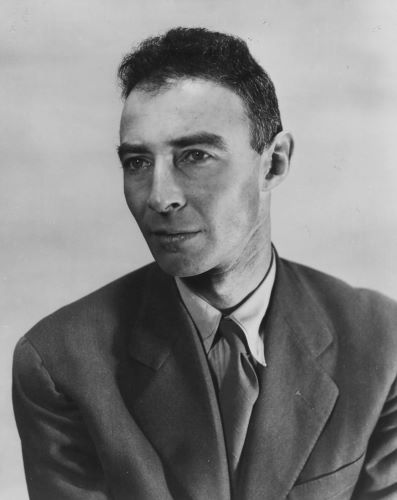

The highly anticipated July 21 release of Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer, starring Cillian Murphy, had many (including us at the History Office) digging into the lesser-known stories of those who contributed to the war effort beyond the scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

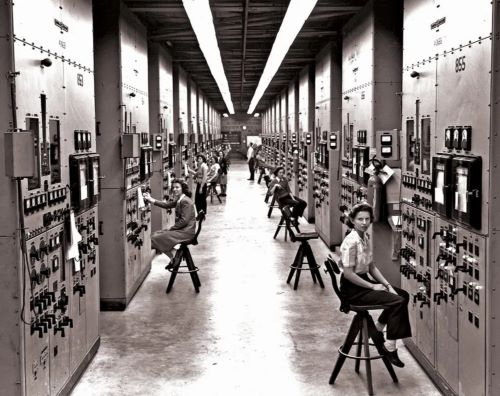

Every day, women such as Ruth Sisson Huddleston boarded a bus headed toward the Y-12 plant. Along the way, billboards with the now-famous message—“What you see here, What you do here, What you hear here, When you leave here, Let it stay here”—reminded her that she was forbidden from talking about her work. In fact, what she was doing was so secret that Huddleston herself was not told the purpose of her labor. She recalled, “I didn’t have any idea what we were doing. We weren’t allowed to even talk to anybody about what we were doing. All I know is they told us we were doing something to help win the war.”

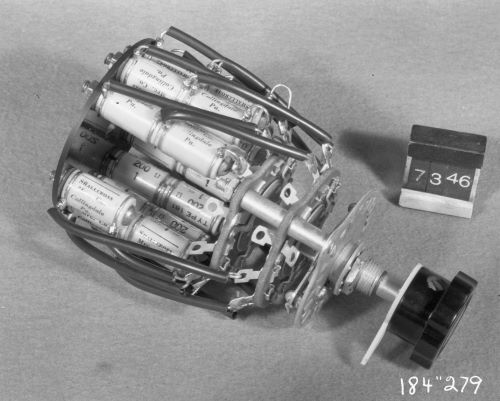

When she arrived at Y-12 for her daily shift, she went to her station, which consisted of a wooden stool in front of a large panel. She spent the next eight hours adjusting handles, knobs, and switches, ensuring that the panel’s needle stayed in a narrow range in the center of the beam. What she and the other workers did not know was that Y-12 was a code name for a uranium electromagnetic separation plant, and these “calutron girls” were harvesting uranium for the first atomic bomb.

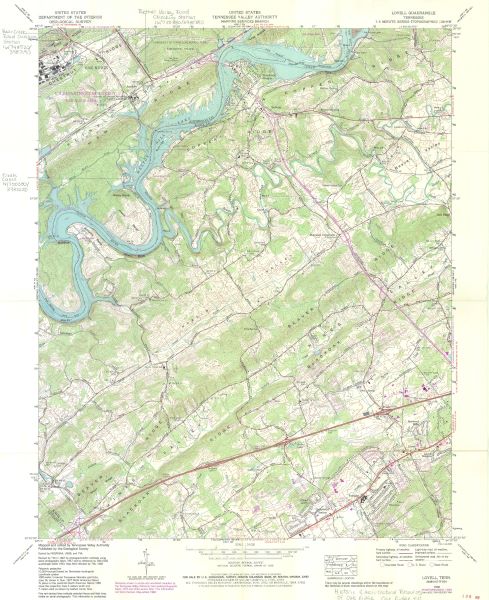

In 1945, the federal government finished building Clinton Engineer Works, a secret city in eastern Tennessee. The compound was part of the closely guarded Manhattan Project, and the site could not be found on any maps. It was codenamed Site X but was known to its inhabitants as Oak Ridge. On the grounds were schools, a newspaper, grocery stores, a post office, laundries, and even roller rinks, restaurants, dance halls, movie theaters, and a rolling library. Of the 75,000 people who lived and worked in the top-secret industrial war site, the vast majority were unaware that the town’s plants were designed to enrich uranium to be used in building an atomic bomb.

The majority of the Oak Ridge inhabitants were women who worked as janitors, mail censors, cooks, chemists, accountants, managers, and phone operators in machine shops and chemical processing plants. The women working at the plants producing uranium were known as “calutron girls.”

Ernest Lawrence, a leader of the Manhattan Project and the inventor of the calutron, employed Ph.D. students to operate the calutrons at the University of California, Berkeley. Lawrence also wanted his students to operate the machinery at the Oak Ridge facilities, but due to labor shortages, he reluctantly agreed to train young women instead, many of whom were recent high school graduates from the local areas.

Most women in eastern Tennessee had few employment opportunities beyond local textile mills offering low wages. As calutron operators, they earned higher pay, were told they were “helping the boys” overseas, and found new independence by working away from home.

The Y-12 plant contained 1,152 calutrons in total. Each consisted of a vacuum chamber sandwiched between two large magnets. By moving the dials of the calutron, its operators used an electromagnetic process to separate the two charged atoms in uranium tetrachloride into isolated uranium isotopes, uranium-235 and uranium-238 ions. The isolated uranium-235 was the fuel for the atomic bomb.

Isolating enriched uranium was one of the most difficult parts of building the atomic bomb, and these women were initially seen as unqualified due to their lack of education and experience. Lawrence was later shocked to learn that the Oak Ridge women were far outperforming his Ph.D. physicists in harvesting uranium. Believing that his scientists and engineers could produce more enriched uranium than the “hillbilly girls” of Oak Ridge, Lawrence declared a friendly contest between the two groups. But the calutron girls again outperformed the male scientists at Berkeley, proving themselves to be highly capable of operating the instruments.

The calutron girls were made aware of the purpose of their work and the plan to build an atomic bomb from material they helped to create when the U.S. dropped “Little Boy” on the people of Hiroshima, Japan.

Though relieved that the war was over, calutron girls, like Huddleston, carried the knowledge of their critical role in unknowingly helping build the first atomic bomb. “I found out the day after they bombed Japan that we had a part in it,” Huddleston later reflected. “We were producing uranium. I felt like I had a part in helping end the war, but I kept thinking I had a part in killing those people.”

Soon after, most workers left Y-12 as the federal government dramatically scaled down operations at the end of the war and as more effective methods of uranium enrichment were developed.

Calutron girls were only a few thousand of the 125,000 Americans who worked on the Manhattan Project. At first glance, the voices of women like Ruth Sisson Huddleston may appear small, and while their recollections are complex, their labor was integral to Oak Ridge, to the wider war effort, and to America’s memory of World War II.

Originally published by Pieces of History, United States National Archives and Records Administration, 07.19.2023, to the public domain.