What “dance” meant in the Byzantine context is not always clear.

By Dr. Leslie Brubaker

Professor Emerita of Byzantine Art

University of Birmingham

Abstract

This article evaluates the significance of processions in Byzantine Constantinople and the role of dancing within them. Evidence is drawn from literary sources concerning imperial, church-sponsored, guild, hippodrome and more spontaneous urban processions, as well as from material culture. Medieval Constantinople saw a large number of processions, perhaps two a week, and they traversed all areas of the city. They were noisy affairs, accompanied by chanting, acclamations and, often, musical noise, so that even when they were not directly visible, they were audible more or less everywhere in the city. Dancing was incorporated in all but liturgical processions (though it may also have been part of these, on occasion). Processions could create a sense of urban unity, or become expressions of conflict: audience participation was normal and sometimes violent. Hence one key-though unofficial-the role played by processions in the Byzantine capital was to give voice to the urban population.

Introduction

The eleventh-century Byzantine polymath Michael Psellos admired the writings of the fourth-century church father Gregory of Nazianzos, and was particularly drawn to his rhythmic writing style. Gregory’s sermons were regularly read out in church services, and Psellos envisioned a congregation so enraptured by listening to the reading of one of them that they first murmured among themselves, then cheered along with the rhythmic cadences, until finally some of them began to dance to the rhythm of Gregory’s words:

Starting from the proems, in fact, he proceeds like the mythical Zeus, thundering and lightning; thoughts present themselves continually which no one would expect. There are indescribable beauties and unsayable graces; flowered words and varieties of figures: all this overcomes the hearer, now induces the listener to admiration, now to applaud, now to weave dances on his [Gregory’s] rhythm and feel oneself involved in the events discussed.1

However imaginative and metaphorical the passage, Psellos clearly did not shy from imagining worshippers in church responding physically to Gregory’s sermons, and breaking into spontaneous dance induced by the rhythm of Gregory’s prose. The holy dance was not a foreign concept to Greek theologians, as we shall see. Nonetheless, dancing in the aisles is not an activity that one normally associates with the Byzantines, who are better known for their condemnation of dancing than for any appreciation of it.2 In fact, the sources expose considerably more dancing-in the streets and the aisles-than one might expect.3 Byzantine texts at times mention dancing so casually that it cannot have been a rare event that required justification or detailed description; as we shall see, the compiler of the tenth-century Book of Ceremonies, for example, noted laconically that after winning a race, the charioteer “dances as usual after a victory.”4 As in this instance, dancing is often, though not only, connected with processions, and it is the association between dancing and processions that concerns me here.

What “dance” (choros; χορός) meant in the Byzantine context is not always clear, but rhythmic movement loosely coordinated with music or other sounds seems an adequate working definition, and one that fits with the written and visual evidence. Often, though not always, dancers are portrayed holding each other’s wrists and engaged in some sort of circular procession.5 Processions may be defined as any formalized moving body of people, by which I mean that a procession had, at least at its core, some form of internal ordering:6 an unruly mob streaming out of the Hippodrome is not a procession. Like dancing, processions often followed a loose internal rhythm, frequently associated with the chanting of psalms during liturgical processions (litai) or acclamations during imperial parades. Unlike dancing, scholarship has long recognised the familiarity of processions in late antique and medieval Byzantine urban life.7 Social occasions, such as weddings and, less happily, funerals, involved processions, across the entire Byzantine period.8 The church organised processions; guilds organised processions; and the imperial court organised processions.9 Dancing is associated with many of them, as we shall see. It was always secondary to the processional performance itself; but, I will argue, we cannot fully understand how processions worked unless we understand the role of dancing in them.

Processions

Processions-with or without dancing-were an expensive and time-consuming component of Constantinopolitan urban life.10 They are also an important source for our understanding of civic life, for several reasons, of which five are of particular relevance here.

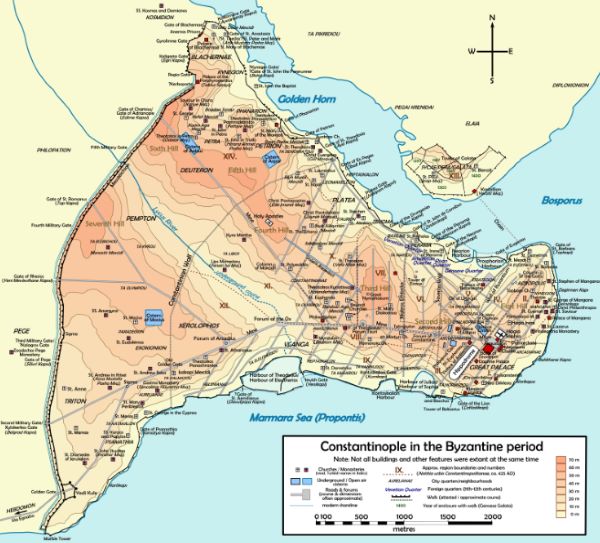

First, processions are about the interaction of people with their material and topographical environment, and as such they provide evidence of how public space expanded and was made fluid. This interaction impacted both the people involved (processors and audience alike) and the material environment: the processors modulated their progress in response to their surroundings, but these surroundings were also often reconfigured to suit the requirements of the procession. This is particularly true in urban environments, and it is certainly the case for Constantinople, as Cyril Mango and Franz Alto Bauer have convincingly demonstrated for the early medieval period.11 To process, and to dance, in the streets required space, and the progressive widening (at, for example, a forum) and narrowing (at, for example, a shop-filled market street such as the Makros Embolos, which still exists as Uzunçarşı, or “long market street”12) of the streets of Constantinople imposed its own rhythm on the procession.

Second, in Byzantine Constantinople, processions involved a lot of people, and not only those with wealth and high social position. The participation of ordinary people is important, even if it is certainly the case that the two major sponsors of processions were the institutional church and the imperial court. Religious ceremonial had involved processions from well before the advent of Christianity, and liturgical and stational processions were incorporated by the fourth century into Christian ritual.13 Processions of all sorts grew in number and frequency from the fifth century onward,14 and by the tenth century, according to the typikon of the Great Church (Hagia Sophia, the main church in Constantinople), there were 66 liturgical processions every year, which works out to slightly more than once a week.15 There are also sporadic records-the first of which dates to 517-of what purported to be a weekly procession between the two major shrines to the Virgin, the Chalkoprateia and the Blachernai, led by the patriarch, but these have left no trace in the typikon of the Great Church.16 How many people walked in these liturgical processions is unclear, but participation was not restricted, and great numbers are sometimes suggested by historical accounts.17 While these may well be exaggerated, the enthusiastic involvement of huge crowds in modern processions was clearly, at least at times, anticipated in Byzantine Constantinople. There is no evidence that liturgical processions involved dancing.

Ruler processions also pre-date Christianity, and the earliest imperial processions in Constantinople were virtually indistinguishable from pre-Christian imperial processions in Rome.18 As recorded by Michael McCormick, the emperor was, in late antiquity, the focus of triumphal entries into the city; after the fifth century these became rare, and were replaced by imperially-sponsored processions that marked a variety of civic and religious events.19 According to the tenth-century Book of Ceremonies, there was roughly the same number of these (65) as there were of for liturgical processions (66), spread across the year; so again over once a week.20 The numbers of attendees remain difficult to establish. Processions within the palace were, according to sources such as the Book of Ceremonies, limited to imperial staff and “the senate” (sometimes including senators’ wives), but outside the palace, the emperor on procession was fair game for petitioners, and from the fifth century onward we find occasional references to guards intended to protect the ruler from the crowd.21 There are certainly many accounts that tell us that “all the populace” greeted the emperor,22 so, like liturgical processions, imperial parades may also at times have been thronged. These processions sometimes involved dancing, particularly when they were celebratory, as we shall see.

It is worth stressing that, although the focus of the procession might be either the emperor (or his representative) or the patriarch (or his representative), it is impossible to distinguish sharply between religious and state processional ceremonial: processions headed by the patriarch often incorporated the emperor, and processions headed by the emperor often ended in a church service led by the patriarch.23 But there were also processions in which neither emperor nor patriarch was involved. Weddings and funerals are obvious examples, and, in addition to these, guilds organised processions, though most of our evidence for these is from the eleventh and twelfth centuries.24 These could involve dancing, and we will return to this shortly. For now, it is the sheer number of processions in medieval Constantinople that is notable, and the range of occasions that prompted them is an important indication of the magnitude of participation in processions in medieval Constantinople. Processions were not the preserve of small isolated groups of people, they were performed by, or impacted on, the great majority of the inhabitants of the city, even if not always at the same time.

Third, processions in Constantinople were interactive. The audiences are frequently mentioned in our sources, and they were not always kind to the processors. As we have already mentioned, by the fifth century, the emperor assigned a special official the task of ensuring that order was maintained during processions, but we nonetheless hear of audiences and processors engaging in physical violence and, especially, of audiences taunting the group processing.25 On a more positive note, we also hear about people spontaneously joining in with the processional party, with numbers expanding as the procession moved through the city.26 The evidence suggests that it was hard to avoid processions (more on this in a moment) and, as importantly, that the audience and the processors were often hard to distinguish. Again, one way or another, processions in Constantinople involved virtually everyone in the city.

Fourth, processions were sensory experiences. Music was played, drums were beaten, and people chanted or sang or raised acclamations; horses clip-clopped along the routes, and chariots sometimes banged along the stone streets. Incense was burnt, and roses and sweet-smelling herbs were strewn along the routes,27 which may have mitigated the stench of the crowd and the horses. People and animals bumped into each other, and into the buildings along the routes.28 Food was sometimes distributed, though normally at the end of the procession (which is also when the host was consumed at certain liturgical processions as well).29 Sight was obviously involved, not only from the ever-changing vision of the cityscape that the procession entered, but in addition the routes were routinely decorated with garlands, textiles and metalwork, hanging from the porticoes along the streets and the windows of buildings,30 and from the tenth century onward icons were routinely made the visual focus of both ecclesiastical and guild processions.31 Descriptions and images of processions provide some of our best evidence for the sensory lives of medieval people, though one that has not yet been exploited by recent studies on the senses in Byzantium.

Fifth, processions provide evidence of participation on multiple social registers, from the imperial family and their retinue and the patriarch, to ordinary people (both in the processions and in the audiences) and the workers who decorated the streets and cleaned up afterwards. Most of these people are invisible in high-status documents, but even courtly protocol occasionally mentions the workers and the cleaners.32 Processions thus give us rare, if oblique, glimpses of the great majority of urban dwellers of Constantinople.

One final note before we turn to processions and dancing: processions followed two main routes, established by the mid-fifth century and in use, at least sporadically, ever after. The first of these ran from the military grounds at Hebdomon (sited, as its name suggests, at the seventh milestone outside the city), through the Golden Gate, to Constantine’s Forum and on to the Great Palace. A second branch led from the Charisios Gate (now Edirne kapı) past Constantine’s mausoleum and the church of the Holy Apostles and met up with the main road at the Forum of Theodosios.33 It is evident from the sources, however, that processions often deviated from these routes, and that there were many other routes as well. Examination of the best-attested routes between the mid-fifth century and the year 1000 makes it clear that large portions of the city were periodically invaded by processions.34 Given the noise that accompanied them, it must have been virtually impossible to avoid processions in medieval Constantinople.

Dancing

Dancing as part of public rituals had a long history in antiquity and some of these roles survived Christianity.35 As Ruth Webb has shown, mime and pantomime, both of which involved dance, were the chief late antique legacies of ancient theatre: mime assimilated comedy and pantomime-sometimes called “rhythmic tragic dancing” in inscriptions-swallowed tragedy.36 Pantomime and mime were originally performed in theatres, but by around 400, as Alan Cameron demonstrated long ago, they had moved to the hippodrome, alongside chariot racing.37 The dancing associated with the circus could-and did-lead to violence, for which reason it was routinely banned, and the dancers exiled. As Webb noted, none of the sanctions were successful:

The claim that Nestorios, bishop of Constantinople from 428 to 431, chased the dancers out for good is wishful thinking. The ban on pantomime by Anastasios I in 502… did not last… In the same way, the festival of Maiouma, which involved pantomime dancing, survived several bans and was still being celebrated in 535.38

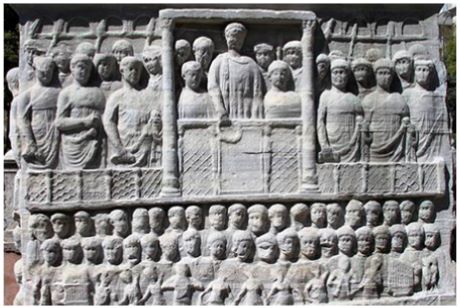

Dancing was not, however, always condemned, even that associated with the hippodrome, where it was performed both by pantomime artists and by the charioteers themselves.39 It is often allied with the factions, the supporters of the four teams of chariot racers of which the main pair were the Blues and the Greens. In addition to supporting their own dancers (pantomimes), who apparently performed between races (as seen on the reliefs from the obelisk base erected in the late fourth century for Theodosios I (379-395) that still survives in the hippodrome in Constantinople (Fig. 1),40 members of the factions and the charioteers themselves also danced as part of victory festivities, in celebration of either the winning charioteer or, on various occasions, the emperor. The seventh-century historian Theophylakt Simokatta, for example, tells us that, on hearing that imperial troops had defeated the Persians outside Nisibis, the emperor Herakleios “decreed that chariot-races should be held and ordered the factions to dance in triumph as is the custom for Romans when they celebrate.”41

Not all dancing, however, was associated with the organised performances of the hippodrome. The role of spontaneous dancing at celebrations is clear from John Chrysostom (ca 400), who casually refers to dancing in the streets to celebrate a military triumph.42 It is particularly eloquently expressed by Corippus, in his In praise of Justin II, written in 565:

When all was quiet the happy people decorated the holy walls throughout the city by garlanding the buildings… They decorated the doorposts and adorned the thresholds with reeds, and stretched festive covering in all the streets. Then the young men began to make merry and add praises to praises; they applauded with their feet, and stepped out in sweet steps and made new songs with wonderful tunes.43

After this, with one notable exception, until the tenth century there is little written information on dancing except condemnations from the church. Already in the fifth century, churchmen associated dancing with un-Christian behaviour: Chrysostom (among others) complained about women dancing at funerals, which he saw as a pagan hold-over;44 Sokrates tells us the Cyril drove the Jews out of Alexandria in the 420s because they were promoting “an evil that has become very popular in almost all cities, a fondness for dancing exhibitions.”45 Canon 62 of the Council in Trullo (691/2) famously forbade public exhibitions of dancing: “we abolish public dances by women, which may cause great harm and mischief, and also the dances and rites performed either by men or women in the name of those whom the pagans falsely called gods.”46 The distinction is gendered: under no circumstances should women move rhythmically in public, while for men (and also women, but this is a secondary consideration) the major objection was involvement in pre-Christian rituals. Both Corippus’s Praise and the Trullan ruling indicate that the earlier condemnations of performative dancing by patriarch Nestorios and the emperor Anastasios I (noted above) had proven ineffective. And, as Nicoletta Isar has observed, churchmen who routinely condemned inappropriate dancing also regularly invoked the celestial dance of angels around the lord.47 It is clear that dancing could be either appropriate or inappropriate, depending on the context in which it was performed: in his sermon on Matthew 48 (ca 400), John Chrysostom wrote “Where there is dance there is the devil” but, later in the same sermon, noted that “God gave us feet […] not so that we could disfigure out bodies, not so that we could prance like camels […] but so that we might dance with angels.”48 In any event, both textual evidence from the tenth century and images that show dancing as part of a procession suggest that the Trullo churchmen were no more successful than had been the patriarch Nestorios and the emperor Anastasios before them.

Dancing for Victory

Dancing associated with triumphal and victory processions, after the late antique evidence that we have already looked at, resurfaces in the tenth-century Book of Ceremonies. Here, Book I (§69) outlines the protocol for chariot races, and notes that the charioteer “dances as usual after a victory,” while the winning team members “dance on chariots” (surely a rather precarious activity) as they parade around the turning post.49 The following chapter (§70) provides the specific example of the races held on the birthday of the city, 11 May, and tells us that the victorious team “having danced as far as the turning-post” goes up to the Stama and asks permission “to go out and dance in the street, and when they have been granted the request by the emperor they go out into the Mese,” the main thoroughfare of the city.50 Book II, chapter 15 records the hippodrome race that marked an exchange of prisoners between Byzantium and the Abbasids in 946, during the reign of Romanos II and Constantine VII, and tells us “When the Blue faction was victorious, a dance was held as prescribed for the vegetable hippodrome festival [part of the 11 May birthday celebrations], that is to say, with the victors escorted by the four scene-painters and all the craftsmen of the two factions […].”51 The hippodrome festival itself is described in Book I (§71), and here again the victorious charioteers dance around the Stama in their chariots, and then “they go away dancing in the streets.”52

Toward the end of this long and rather repetitive chapter-a mishmash which Gilbert Dagron suggested is composed of extracts from different periods concerning a variety of celebrations53-is a sequence of almost antiphonal responses between “the cheerleaders” (hoi kraktai) and “the people” (ho laos) that expands on this same sequence. The cheerleaders say “Let us go away and dance, rulers, if you command it” and, after acclaiming the rulers, the official in charge of the hippodrome (the aktouarios) crowns the victorious charioteers and tells them to “Dance in proper order,” to which the cheerleaders respond “We shall dance in proper order while you live, rulers.” The factions (and, apparently, the people) then leave the hippodrome, and go to the churches favoured by the Blues and Greens, respectively.54 Here the actual dancing in the streets is not mentioned, but we are probably meant to infer, from the preceding passages, that the factions (and the people?) danced in the streets and then went to (or danced on their way to) church. In any event, if these accounts record actual behaviour, there was indeed regular dancing in the streets of Constantinople in the tenth century, and thus, presumably, continuously from the fifth and sixth.55

Byzantine Images of Dancing in Processions

This continuity is equally demonstrated by images.56 The dancing women portrayed on the base of the Theodosian obelisk in the hippodrome (Fig. 1) seem to be providing localised entertainment rather than moving as part of a parade, and a later parallel to dancing as entertainment divorced from any obvious processional setting is provided by the dancing women on the so-called crown of Constantine Monomachos (Fig. 2).57 In contrast, late antique textiles and a sequence of images from the ninth century onwards clearly depict dancing as part of processions associated with triumphs or victory celebrations-as, indeed, are the dancers on the obelisk base, though without the processional aspect. The late antique examples, which I will not focus on here, have been studied and published by Eunice Dauterman Maguire;58 the later examples appear in two contexts: representations of David’s entry into Jerusalem after the defeat of Goliath, and, based on this, a triumphal imperial entry into a city on a late Byzantine ivory pyxis at Dumbarton Oaks; and miniatures of the Crossing of the Red Sea with the dance of Miriam.

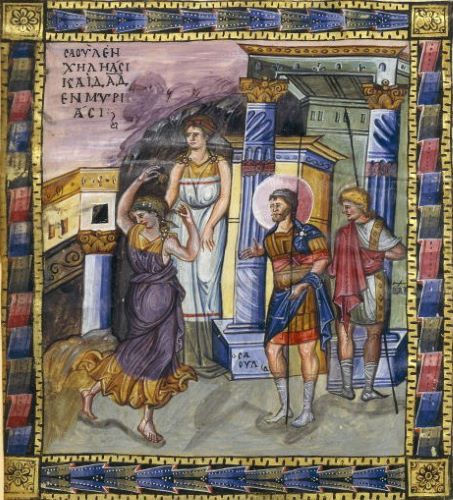

Images that visualise dancing as part of a victory procession illustrate David’s entry into Jerusalem after his defeat of Goliath (I Kings 18.6-7) on the ninth-century ivory box now housed in the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, in the ninth-century Sacra Parallela, and in the eleventh-century Vatican Book of Kings (Fig. 3).59

In the latter, the dancers are arranged in a circle welcoming David on his return, an image that finds an echo in the miniature accompanying Psalm 151.6-7, a passage celebrating the victory over Goliath, in the (also eleventh-century) Vatican Psalter (BAV gr.752, f.449v: Fig. 4), though here the dance of Miriam is also referenced (see below).60 A dancer also appears in this context in the tenth-century Paris Psalter, and musicians (but no separate dancer) in the eleventh-century Theodore Psalter.61 The late Byzantine pyxis now at Dumbarton Oaks, which shows a dancer and musicians entertaining the imperial family translates this Davidic theme into contemporary politics.62

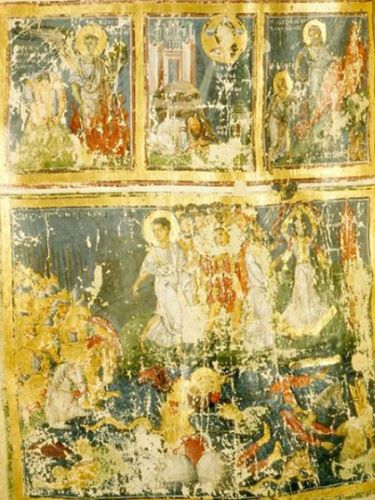

The David images suggest that the victory dancing in the Book of Ceremonies was not simply a literary trope. Further to this, images of Miriam’s dance celebrating the successful crossing of the Red Sea by Moses and the Israelites (Exodus 14.21-31) provide the clearest examples of dancing as part of a procession to survive from the Byzantine empire. The earliest preserved examples survive in three ninth-century manuscripts, the Paris Gregory of 879-882 (Fig. 5) and two psalters with marginal images that are perhaps slightly earlier than this, the Khludov Psalter and Mount Athos, Pantokrator 61.63 In all three, the Israelites process to the right, away from the drowning Egyptians, while Miriam dances in celebration at the head of the parade, a reference to Exodus 15.20-21: “And Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, having taken a timbrel (tympanon) in her hand-then there went forth all of the women after her with timbrels and dances. And Miriam led them, saying, let us sing to the Lord, for he has been greatly glorifed: the horse and rider has he cast into the sea.”64 Miriam is depicted alone, in the ninth-century miniatures, and is a striking figure, apparently whirling in abandon, arms raised and holding krotales (castanets), with her long hair streaming around her.65 This is a rare example of a “good” woman shown with her head uncovered in Byzantine representations, and an equally unusual portrayal of a physically active non-imperial woman.66 However exceptional in its Byzantine context, however, its ultimate source is clear: Mati Meyer has tracked the motif from Dionysiac imagery to the dancers on the Theodosian obelisk base, a fourth-century personification of April on a mosaic floor from Carthage, a fourth- or fifth-century wooden box from Egypt, and a maenad depicted in mosaic in a sixth-century house in Madaba.67 Once enfolded in a Byzantine religious context, dancing women are primarily associated with the Mosaic tradition, and appear largely in psalter illustrations.68 The representation of a respectable woman abandoning herself to dance, with her head uncovered and her hair loose, would have been possible in Byzantium only in a context that sharply distanced the portrait from contemporary realities-and the Jewish Miriam, unaffected by the churchmen’s strictures against women and Jews, provides that context.

The eleventh-century miniature in the Vatican Psalter of the women of Israel, led by Miriam, dancing (Fig. 4) is however quite distinct.69 It accompanies the supernumerary psalm 151, which references David’s triumphant entry into Jerusalem after the slaying of Goliath, and is also located immediately before the Moses Ode (Exodus 15.1-9), which celebrates Moses leading the Israelites safely across the Red Sea and the destruction of the Egyptians who pursued them. The women of Israel dancing is appropriate to both contexts, though the inscriptions make it clear that it is primarily meant to evoke the dance celebrating the successful crossing of the Red Sea. In any event, the women hold each others’ wrists as they dance-and process-in a circle that, once more, recalls much older Dionysiac motifs,70 though here not only are the women are luxuriously dressed, but they are made respectable by the elaborate hats that cover their heads, with no hair visible. It is tempting-though speculative-to see this as a visual parallel, outside the victory context, to Michael Psellos’s roughly contemporary description of women dancing as part of what appears to have been an annual guild celebration organised by female textile workers on 12 May.71 Psellos described a procession, a ritual involving images of women carding linen and weaving, and, finally, a dance in which the women held each other by the wrist, as they do in the psalter miniature, and turned from side to side.72 What is notable about Psellos’s description is, in the context of this chapter, that it once again pairs processions and dancing with women. The Agathe festival, as this was known, occurred the day after the birthday celebration in Constantinople on 11 May that, as we saw, also involved dancing in the street; it was presumably seen as a continuation of the festivities by a specialised group of workers. This is an important indication that there was more female participation in Middle Byzantine public life than one would suppose from most ecclesiastical texts, and suggests that church laws forbidding women to dance in public contexts were responses to realities rather than just examples of gendered rhetoric.

Dancing at Imperial Celebrations in the ‘Book of Ceremonies’

The Book of Ceremonies specifically mentions dancing several times, in three distinct contexts. I have already discussed the references to victory dancing in connection with the hippodrome and charioteers; three additional passages involve the factions dancing as part of imperial celebrations; and one involves “the people” dancing as part of an imperial birthday celebration for Michael III sometime around 860.

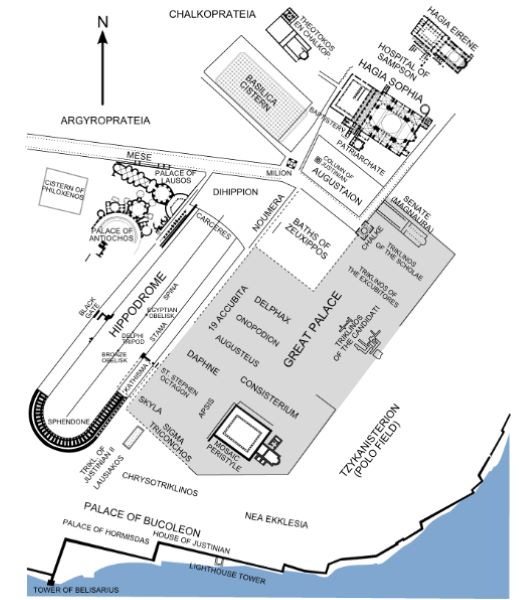

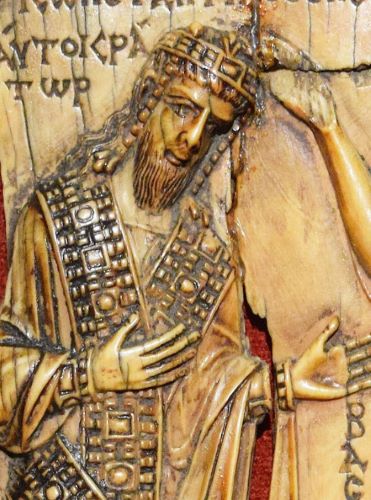

Book I, chapter 65 is titled: “What it is necessary to observe at the dance, that is, at the banquet.”73 We are told that “after the meat course” the officials in charge of proceedings (the atriklinai) “go out and lead in those who are going to take part in the dance,” in this case the Blue faction. After various acclamations, “the steward of the table turns and extends his right hand and spreads his fingers like rays and contracts them again like a bunch of grapes” and then (at this signal), the Blue faction begins to dance, “going around the table in a circle three times.” After further acclamations, the Green faction does exactly the same thing. The chapter concludes: “Note that this whole ceremonial is performed also for the banquet for the augousta.” That this was a regular performance is further suggested by the tag line that appears at the end of the preceding chapter in the Book of Ceremonies, which reads: “Note that on this day dances are not part of the banquet.”74 What is not clear, however, is whether the factions themselves danced or whether there were dancers associated with the factions who danced. In the early years of the City, dancers, paid for by the state, were associated with each faction: it is these women that we see on the obelisk of Theodosios: Fig. 1). By the seventh century, the factions had been absorbed into imperial ritual and, concomitantly, we hear no more of the pantomimes associated with them.75 But, as the Book of Ceremonies makes clear, the factions remained closely associated with celebratory and processional dancing.

Dancing is mentioned several times in the hotchpotch chapter 71 of Book I (“What it is necessary to observe when the Torch Ceremony is conducted”), which we considered earlier for its dancing victory processions.76 The chapter opens with a different kind of dancing, though it still involves the factions: “In the afternoon the two factions go into the private fountain-court of the Triconch with torches, and what is called the Torch Ceremony takes place. They dance and recite the apelatikos [an acclamation]…”77 The chapter then moves on to the hippodrome festival, which involved four races, after which-as we have seen-the victors dance around the Stama and go on dancing in the street. The variety and repetition within this chapter-which suggest that multiple sources of court protocol were synthesised, though not very coherently-hint that dancing processions formed a normal and regular part of imperial ceremonial across time, and this suggestion is reinforced by the remaining two references to dancing in the Book of Ceremonies.

Book II, chapter 18 concerns the Broumalia, the ancient Dionysiac celebration of the new wine harvest, frequently condemned by both the church and, sometimes, the emperor, but regularly revived, at least until the twelfth century.78 The opening of the chapter is missing; it resumes as the emperor and court process to the private fountain court of the Triconch in the imperial palace. Members of the court “from the magistroi [the most senior administrators] to the lowest ranking” light candles and “mass around the Sigma [a semicircular peristyle adjacent to the fountain court], dancing and chanting their particular imperial eulogies for the Broumalion.”79 The text continues:

Note that when the members of the senate and of the kouboukleion [the courtiers who served the emperor and empress] begin to chant the imperial eulogies for the Broumalion and to dance as previously described, one of the emperor’s men goes down via the steps to the fountain court and dances. Both groups, the magistroi and the rest and the members of the kouboukleion with the eunuch stewards of the table, having circled the floor of the fountain court three times as previously described, stand along the broad side of it and cheer the emperor.80

The ceremonies and dancing continue the next day, at a banquet in the Hall of Justinian (also in the imperial palace):

The dance takes place following the specific format with regard to the list of precedence, and the magistroi, proconsuls, patricians, holders of high office, and protospatharioi [a high-ranking courtier] go in to the dance and dance following the prescribed format. If some of them are seated at the banquet, they stand up and take their part in the dance, and again, at the command of the emperor, they sit, each in his own order. Note that for the dance those mentioned all go in together, but in the songs, that is, the imperial eulogies for the Broumalion sung antiphonally, they separate.81

There follow specific details about variant arrangements for the banquet under Leo VI (886-912), and during inclement weather under Michael III (842-867), a note that Romanos I (920-944) cancelled the celebration, and that it was restored under Constantine VII (944-959), following the model of illustrious emperors of the past (listing Constantine I, Theodosios I, Marcian, Leo I and Justinian I).82 Whether or not these earlier august emperors followed the formula outlined in the Book of Ceremonies, the degree of specificity concerning practices from the mid-ninth century until the time of Constantine VII, when the book was compiled, strongly suggests that at least during this period dancing processions were very familiar in the imperial court of Constantinople, a suggestion confirmed by the appearance of “a brightly lit dance” in the specifications for the festival in the Kletorologion of Philotheos, a list of titles and offices compiled in 899.83

This is further confirmed by the final mention of dancing in the Book of Ceremonies, in Book II, chapter 35, entitled “Concerning the dance.”84 It reads:

It should be known that at the dance for the said birthday [of Michael III] the two factions of Blues and Greens of the City body never used to dance. When the praipositos [one of the two head court eunuchs] advised the emperor of this, the emperor commanded that they dance. On the said day the two factions went in, in the fourth and fifth ceremonial group in the dance, and completed the whole dance and received a purse.

In other words, a dance was added to the ceremonial protocols of the imperial palace in the mid-ninth century, and the pattern was familiar enough that (as in Book II, chapter 18 on the Broumalia where the factions danced “following the prescribed format”) we are expected to know the formula, and are simply told that the participants “completed the whole dance.” If this followed the models we have previously discussed, which seems probable, the factions processed and danced, perhaps in a circle as they did for the Broumalia, or, less likely perhaps, in a line out onto the street, as they did for other festivals. That the circular procession is more likely is suggested by the Kletorologion, which cites dances regularly in its list of ceremonial protocols, though rarely with any detail: we hear, for example, that on the thirteenth day after Christmas, there is “a reception with a dance,” and on 21 July “hospitality in the form of a reception and great dance takes place.”85 That at least some of these dances involved dancing in processional circles is, however, indicated by Philotheos’s account of the activities of 30 August, during the joint rule of Leo VI and his brother Alexander (879-912), when, we are told, “half the total number” of the élite courtiers attend a banquet and “It is necessary to allocate all the rest to the dancing for the delight of the ruler. They dance in a circle in gold pectorals and devise eulogies for the pious rulers.”86 From this account, it would appear that the circular dances recorded in the Book of Ceremonies had a history that was familiar enough to be recorded laconically in earlier books of protocol, and the even less detailed notations of dances elsewhere in the Kletorologion suggest that dancing, in whatever variant form, was a long-standing part of the ceremonial fabric of certain court processions.

Conclusion

So we may conclude that there was dancing in the streets of Constantinople, and that this frequently occurred as part of processional activities organised by the factions and by the guilds. Performance may also have been spontaneous at times, as suggested by the sixth-century text by Corippus (and possibly the eleventh-century passage by Psellos with which we opened this article), but this is not something we hear about with any regularity.

This conclusion is significant for several reasons. Perhaps most notably, it has simply never before been noticed that dancing was a regular and unremarkable part of social performance in the Byzantine capital. We are so accustomed to thinking of the Byzantines as acting within formal and hierarchical straight-jackets that it comes as a considerable surprise to realise that this was not always the case. Equally startling, from the standpoint of the traditional view of Byzantine society, is the role of women, and the accepted public participation of “respectable” women in both processions and processional dancing. In the Middle and Late Byzantine periods, images of dancing, in fact, almost invariably show women,87 not men, though men are sometimes (though not always) responsible for the music to which the women dance.

Processions are, it seems to me, critically important to our understanding of urban life in Constantinople from the beginning until at least the take-over of the city by the Latins as a result of the Fourth Crusade in 1204. For all of the reasons outlined at the beginning of this chapter, the civic performance of processions is more revealing of the lives and activities of the whole gamut of people who lived in Constantinople-from the street cleaners to the emperor and the patriarch-than any other activity we know about. The sensory ambiance of all processions was extraordinary by modern standards. Processions were noisy from worshippers chanting the psalms or people acclaiming the emperor, not to mention the noises made by people, horses and chariots pushing their way through crowded streets and market squares, sometimes playing drums and musical instruments. They were smelly from those same markets, people and animals, a stench partially offset by incense, roses and sweet-smelling plants. Processions were frequent and physically challenging from the at times very long routes, some of which began at dusk to reach the relevant church by dawn.88 Most of them involved physical contact, not always polite, between the other people and animals processing, as well as the audience and the buildings along the route; they were visually stimulating by the decorations put up along the route or the icons and relics carried along; and sometimes, at the end, they also involved taste through the ceremony of the eucharist or, more prosaically, the consumption of food (and of course one could always self-provision along the way from the market stalls lining the route). The Constantinopolitan procession provided sensory overload, for everyone in the city, processors and audience alike. It could also provide a strong sense of community, sometimes united and sometime oppositional. Dancing as part of the performance was, so far as we can tell, always part of the communally unifying aspect of processions, bringing with it, at least on occasion, a sense of fun-another emotion rarely attributed to the Byzantines-and communal celebration. And in this respect it also did something else as well: it brought together what we might call the realm of Caesar-dancing to commemorate a victory; dancing in celebration of one’s livelihood-and the realm of God, transported by the rhythmic cadences of a sermon, or dancing in celebration with the angels.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by the Culture & Digital History Journal 11:2 (December 2014), DOI:https://doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2022.014, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.