The past is not a possession. It cannot be legislated into stability. It is always under negotiation. To write it, as a historian, is to join that negotiation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Historian and the Leviathan

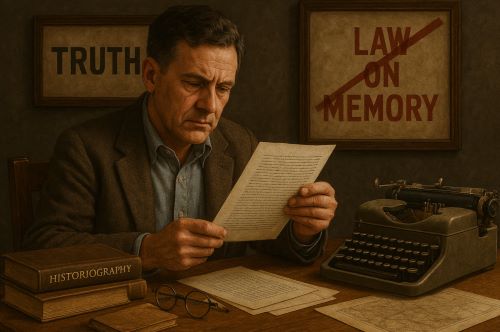

To write history is to wrestle with power. In the twentieth century, the historian’s task became a political act as never before, not simply because the century was marred by genocides, total wars, and revolutions, but because the memory of those events was, and remains, a battleground. Governments and institutions sought not only to make history but to own it. They passed laws that enshrined particular versions of the past, criminalized dissenting narratives, and curated public memory as a form of statecraft. The courtroom, the classroom, and the archive became arenas of ideological enforcement.

What was once an epistemological problem, how to know the past, became, in modernity, an existential one: who gets to speak for it? The rise of memory laws across the globe, aimed at protecting or prosecuting specific historical interpretations, signals a transformation in the role of history itself. These laws did not emerge from nowhere. They were, in a sense, the culmination of a long historical anxiety: that truth, once uncovered, could still be denied; that suffering, once endured, could still be erased. Yet the urge to legislate truth may protect some wounds even as it represses the historian’s critical inquiry.

Laws of Memory, Trials of Truth

Nowhere is this dynamic more evident than in the historiography of the Holocaust. In the aftermath of the Shoah, the world stood briefly at the edge of historical reckoning. The Nuremberg Trials, despite their legal novelty, represented an attempt to place atrocity within the framework of documentation, evidence, and responsibility. Yet even as Nuremberg elevated the value of historical record, it also initiated a legal model through which states would begin to govern memory.1

By the late twentieth century, Holocaust denial laws had become widespread in Europe. France’s Gayssot Law (1990), Germany’s Volksverhetzung statutes, and similar measures in Austria and elsewhere made it a crime to contest the established facts of the Holocaust. The impulse behind these laws is morally understandable; they were forged in the shadow of real trauma and justified as bulwarks against the resurgence of fascism. But they also raised difficult questions for historians. What happens when a state claims to protect truth by fixing it? Can the historical method survive in a climate of enforced consensus?

Pierre Nora, the French historian of memory, warned against what he called the excesses of memory, a cultural climate in which remembrance becomes compulsive, ritualized, and policed.2 In such a climate, history risks being subordinated to commemoration. To challenge prevailing memory is to risk heresy, even when the challenge is methodological rather than ideological.

Erasure and Denial: The Silence around Empire

While Western Europe confronted its crimes through memory laws, other regions moved in the opposite direction – denying, repressing, or reconfiguring the past to serve national cohesion. The Armenian Genocide remains perhaps the most glaring example. Despite a century of scholarship, survivor testimony, and archival evidence, Turkey has refused to officially recognize the mass killing of Armenians as genocide.3 Rather than denial in the open sense, this is a strategy of erasure through euphemism, legal intimidation, and diplomatic pressure.

In 2005, the Turkish government prosecuted the Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk for “insulting Turkishness” under Article 301 of the penal code, simply for publicly acknowledging the Armenian and Kurdish massacres.4 The law was not about historical accuracy but national honor, a clear example of how historical truth can be subordinated to an imagined communal dignity. In this model, the state is not the guardian of memory but its censor. Historians who speak against the grain become dissidents, not scholars.

The case of France again presents a contrast. In 2001, the French Parliament passed a law recognizing the Armenian Genocide, aligning with memory’s demands. Yet, in a twist, a subsequent attempt to criminalize genocide denial in this context was struck down by France’s Constitutional Council, which argued that legislating historical interpretation violated freedom of expression.5 The episode revealed the ambiguity at the heart of memory laws: they claim to defend truth, yet in doing so may impede the very discursive space in which truth is debated and refined.

Stalin’s Shadow and the Post-Soviet Struggle for Narrative

The fall of the Soviet Union did not liberate history; it unleashed a war for it. Throughout the former Soviet republics, the legacy of Stalinism became the object of renewed contestation. In Russia, early attempts to expose Stalin’s crimes in the 1990s were soon overshadowed by a wave of neo-patriotic revisionism. Under Vladimir Putin, state-sponsored narratives began to rehabilitate aspects of Stalin’s reign, emphasizing industrial modernization and wartime leadership while downplaying the terror, purges, and gulags.

In 2014, Russia passed a law criminalizing the “distortion” of the Soviet role in World War II, punishable by fines or imprisonment.6 Though framed as a defense against historical “falsification,” the law has been used to suppress critical scholarship and marginalize dissident voices. Memorial, a Russian human rights group and archival organization that had long documented Stalinist abuses, was declared a “foreign agent” and ultimately dissolved by the Russian courts in 2021.7 The message was unmistakable: history belongs to the victor, even when that victory is over memory itself.

Historians in post-Soviet spaces face a paradox: their professional task is to uncover the past, yet their national duty, as increasingly defined by the state, is to revere it. The line between revisionism and patriotism is deliberately blurred. Under such conditions, historical inquiry does not merely challenge official narratives; it constitutes a form of resistance.

Between Academic Freedom and National Myth

Faced with these constraints, historians have responded in different ways. Some retreat into the archival shadows, focusing on microhistories or obscure topics to avoid political controversy. Others embrace public engagement, challenging nationalist myths in essays, films, and digital platforms. The historian becomes not just a scholar but a civic actor.

The tension between national myth and academic freedom is not merely philosophical; it has real institutional stakes. Curricula are rewritten, funding is denied, access to archives is restricted. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s government has reshaped historical memory through cultural policy, erecting monuments that exonerate Hungarian complicity in the Holocaust while promoting a narrative of eternal victimhood.8 The goal is not education but identity construction.

In the United States, similar struggles have emerged around how slavery, Indigenous genocide, and settler colonialism are taught. While the state does not mandate specific historical interpretations at the federal level, battles over school curricula and textbook content reflect the same anxiety: that history, if told honestly, may unsettle the moral foundations of national identity.

Historiography is not neutral. It has never been. But the danger lies not in recognizing history’s contested nature. The danger lies in allowing only one contestor.

The Ethics of Writing the Past

What, then, is the historian’s ethical task in a world where history is weaponized? It is neither to retreat into the fantasy of objectivity nor to adopt the posture of the activist without rigor. Rather, it is to hold the line, to insist that critical inquiry, archival fidelity, and conceptual openness must not be sacrificed to the demands of political expediency or national pride.

Memory laws, state censorship, and institutional pressures all attempt to draw a border between acceptable and unacceptable histories. Yet history itself is a border-crossing act. It trespasses against sacred myths, interrupts national liturgies, and asks uncomfortable questions. That is its power.

The past is not a possession. It cannot be legislated into stability. It is always under negotiation. To write it, as a historian, is to join that negotiation, and to resist those who would end it.

Appendix

Footnotes

- See Donald Bloxham, The Final Solution: A Genocide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 232.

- Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations 26 (1989): 7–24.

- Ronald Grigor Suny, They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else: A History of the Armenian Genocide (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 347.

- Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France since 1944, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 213.

- See discussion in Dan Diner, Cataclysms: A History of the Twentieth Century from Europe’s Edge (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007), 284–85.

- Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 393.

- Patricia Cohen, “Russia’s Revisionist History Finds a Home in U.S. Classrooms,” The New York Times, May 4, 2021.

- Cohen, “Russia’s Revisionist History.”

Bibliography

- Bloxham, Donald. The Final Solution: A Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Cohen, Patricia. “Russia’s Revisionist History Finds a Home in U.S. Classrooms.” The New York Times, May 4, 2021.

- Diner, Dan. Cataclysms: A History of the Twentieth Century from Europe’s Edge. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007.

- Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations 26 (1989): 7–24.

- Rousso, Henry. The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France since 1944. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else: A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.