Air Force One promises transparency while enclosing secrecy. It represents accessibility while embodying insulation. It is a vehicle of diplomacy and an icon of hierarchy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Flight, Presidency, and the Aerial Republic

To watch Air Force One ascend into the sky is to witness more than the mechanical triumph of aerospace engineering. It is to see the presidency itself take flight, a vessel at once technological, symbolic, and theatrical. Unlike the White House, rooted in marble and classical stasis, this plane is a structure in motion. It carries with it not only the commander-in-chief but also the full freight of American mythology: power projected with lift and thrust, diplomacy conducted in midair, and the paradox of a mobile executive rooted in constitutional restraint.

The story of Air Force One is not simply the history of a plane. It is a study in how mobility reshapes authority, how technology reconfigures perception, and how political theater adapts to the aerial stage. From Roosevelt’s daring wartime flights to the Cold War’s carefully choreographed descents, the presidential aircraft has become a floating annex of the American state. To trace its development is to chart a shifting landscape of image, security, and global reach.

Origins of Flight: Roosevelt, Wartime Necessity, and the Sacred Body of the President

First in the Air: The Dixie Clipper and Sacred Geography

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the first sitting president to fly while in office, a decision shaped not by symbolic ambition but by the logistical realities of global war. In 1943, FDR boarded the Dixie Clipper, a Pan Am flying boat, to attend the Casablanca Conference. The journey was extraordinary. It marked the crossing of a psychological threshold as much as a geographic one. For the first time, the American president was airborne, untethered from the continent yet responsible for its fate.1

The act carried layered meanings. To fly was to risk exposure. For a president partially paralyzed and keenly aware of the physical image he projected, air travel posed both vulnerability and necessity. Yet it also situated the president in a space of mobility that wartime geopolitics increasingly demanded. Casablanca was not a leisure voyage. It was a crucible in which Roosevelt, Churchill, and de Gaulle forged strategy while the American public remained largely unaware of how precarious the journey had been.2

The flight established a precedent. From this point forward, the air became a legitimate and increasingly necessary domain of presidential activity. The president, like the nation itself, was no longer grounded.

The “Sacred Plane”: The Sacred Cow and Postwar Adaptation

Roosevelt’s 1945 trip on the Sacred Cow, a Douglas VC-54C built specifically for presidential use, deepened the symbolic fusion between aircraft and executive body. The name itself suggests both reverence and absurdity. Though the Sacred Cow saw limited use, it introduced key features that would shape all future presidential aircraft: secure communication lines, a private stateroom, and strategic adaptability.3

Its mere existence illustrated how military priorities had fused with presidential logistics. The postwar world demanded speed, secrecy, and aerial diplomacy. It was no longer enough for the president to travel. He had to do so with infrastructural sovereignty.

Eisenhower and Jet Power: The Cold War and the Modernization of the Sky

Columbine III and the Art of Appearances

President Dwight D. Eisenhower brought a general’s pragmatism and a Cold Warrior’s understanding of optics to the skies. His aircraft, Columbine II, a Lockheed C-121 Constellation, became more than a means of transport; it was a strategic asset. It allowed him to visit allies, inspect bases, and project calm strength.4

Yet even this elegance was transitional. Propeller planes, however polished, could not match the emerging jet age’s symbolic velocity. The aircraft had become an extension of national identity. Slowness suggested vulnerability.

In 1959, Eisenhower became the first president to fly in a jet, aboard a Boeing 707, designated SAM 970. The shift from propeller to jet was not merely mechanical. It marked a break with the past. It was the birth of modern presidential aviation.

The Call Sign Crisis: Birth of “Air Force One”

A 1953 incident, seemingly trivial, proved decisive in shaping public and military understanding of presidential flight. When an Eastern Airlines commercial plane carrying the same call sign as the president’s aircraft entered the same airspace, the danger became apparent. To avoid future confusion, the distinct designation Air Force One was adopted.5

The name caught hold quickly. It gave the presidential plane a mythic weight. From a logistical necessity emerged an icon. Air Force One was now not only a physical object but a discursive space, evoked in headlines, political satire, and cinematic spectacle.

Kennedy, Branding, and the Aesthetic of Power

The Jet Age and Raymond Loewy

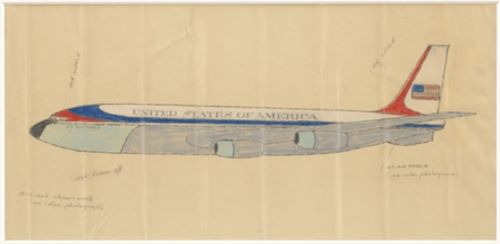

When John F. Kennedy entered office in 1961, he inherited a jet-powered presidency and gave it visual form. Working with designer Raymond Loewy, Kennedy approved a sleek blue-and-white livery with a distinct presidential seal and refined serif typography. The design eschewed military harshness in favor of elegance and soft authority.6

This aesthetic intervention was not superficial. It represented a conscious branding of American power, graceful, modern, and mobile. The aircraft became part of Kennedy’s broader strategy of visual diplomacy. When he descended from Air Force One in Berlin, in Paris, or in Dallas, he did so not just as a statesman but as a curated image.7

The aircraft now functioned as a stage. Its stairs became a portal through which American power could be dramatized and displayed.

Crisis, Continuity, and the Flight from Dallas

Perhaps the most poignant and mythic moment in Air Force One’s history came on November 22, 1963. Following Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon Johnson took the oath of office aboard the aircraft, with Jacqueline Kennedy by his side, still in her blood-stained dress.8

The moment was saturated with symbolic tension. In the liminal space between death and succession, Air Force One became the cockpit of constitutional continuity. The swearing-in reinforced the legitimacy of the republic while flying above a stunned nation.

This single act transformed the aircraft forever. It was no longer merely a vessel of power. It had become a site of mourning, of legitimacy, of statecraft at 30,000 feet.

Nixon, Reagan, and the Cold War Theater of the Sky

Nixon’s Air Diplomacy

Richard Nixon, always attuned to gesture and ritual, used Air Force One as a platform for global diplomacy. His trips to China and the Soviet Union, though meticulously choreographed, were imbued with spontaneity due in part to the presence of the plane.9

Its landing was a statement. Its presence, unmistakable. With each touchdown on foreign soil, Air Force One delivered not just an individual but an ideology, a vision of American resolve carried across hemispheres.

Reagan’s Mythmaking and the Empire of Optics

Ronald Reagan inherited this apparatus and transformed it into a theater of triumph. With the aid of Reagan-era media choreography, the aircraft became a backdrop for cinematic presidentialism. His speeches beside it, his confident wave at the top of the stairs, all were saturated with intentional symbolism.10

In Reagan’s presidency, Air Force One was less a tool of diplomacy than an icon of narrative. It was where the president could appear sovereign, accessible, and elevated, literally and figuratively.

Post–Cold War to the Present: Transformation and Threat

The 747 Era: SAM 28000 and Technological Ascendancy

The two Boeing 747-200B aircraft introduced during George H. W. Bush’s presidency, SAM 28000 and SAM 29000—remain in use today. These aircraft expanded the scale, autonomy, and complexity of the flying White House. Equipped with secure communication systems, defensive countermeasures, and enough onboard power to serve as a mobile command center, the plane was now a Cold War bunker in the sky.11

Its internal layout (conference rooms, medical suites, press cabins) mirrored the bureaucratic ecology of modern governance. It was less personal, more functional. The aircraft now encapsulated the post-Cold War presidency: fortified, media-savvy, and globally omnipresent.

September 11 and the New Aura of Isolation

On September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush was flown on Air Force One from Florida to Louisiana, then to Nebraska, in an effort to ensure his safety amid chaos. The aircraft became both shield and symbol, aloof and unreachable.12

Critics lamented the president’s absence from the capital. Supporters saw it as prudent. Either way, the plane was now a symbol of emergency governance, of a presidency both protected and, at times, inaccessible.

From that day forward, the aircraft has stood not only for power but for vulnerability, a reminder that the skies, once a space of triumph, can also be spaces of terror.

Conclusion: Myth on the Tarmac

Air Force One is not a plane in the ordinary sense. It is a ritual object, a floating fortress, a stage of perpetual arrival. Its history reveals how the American presidency has adapted to speed, spectacle, and globalism. But it also reveals the contradictions of that adaptation.

The aircraft promises transparency while enclosing secrecy. It represents accessibility while embodying insulation. It is a vehicle of diplomacy and an icon of hierarchy. Like the presidency itself, it is part real, part theater; its jet engines pushing forward while always circling back to the nation’s founding myths.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Robert Dallek, Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 440–443.

- Conrad Black, Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom (New York: PublicAffairs, 2003), 984.

- Kenneth T. Walsh, Air Force One: A History of the Presidents and Their Planes (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 22–25.

- David Eisenhower, Eisenhower: At War, 1943–1945 (New York: Random House, 1986), 583.

- Walsh, Air Force One, 38–40.

- Hugh Sidey, The Presidency and the Press (New York: Trident Press, 1966), 214–217.

- Thurston Clarke, JFK’s Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President (New York: Penguin Press, 2013), 273.

- Ibid., 288–291.

- Richard Reeves, President Nixon: Alone in the White House (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 215–220.

- Lou Cannon, President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 403–406.

- Walsh, Air Force One, 138–145.

- Dan Balz and Bob Woodward, Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), 38–42.

Bibliography

- Balz, Dan, and Bob Woodward. Bush at War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

- Black, Conrad. Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. New York: PublicAffairs, 2003.

- Cannon, Lou. President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

- Clarke, Thurston. JFK’s Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President. New York: Penguin Press, 2013.

- Dallek, Robert. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Eisenhower, David. Eisenhower: At War, 1943–1945. New York: Random House, 1986.

- Reeves, Richard. President Nixon: Alone in the White House. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

- Sidey, Hugh. The Presidency and the Press. New York: Trident Press, 1966.

- Walsh, Kenneth T. Air Force One: A History of the Presidents and Their Planes. New York: Hyperion, 2003.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.