To study this forgotten migration is to glimpse a moment in which the American South briefly looked beyond the nation it had betrayed, hoping to find in foreign empire the means to restore its own.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Defeat, Diaspora, and the Dream of Return

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, as the Confederacy collapsed beneath the weight of its contradictions and defeats, thousands of Southerners looked southward, not toward reconciliation, but toward reinvention. Mexico, under the brief and controversial reign of Emperor Maximilian I, became a distant but tantalizing haven for those unwilling to accept the verdict of Appomattox. What emerged in the years between 1865 and 1867 was a peculiar moment in transnational history: the migration of ex-Confederates into a foreign empire built with French bayonets, Habsburg ambition, and imperial fantasy.

This movement was not merely a desperate flight from Northern occupation. It was a conscious attempt to preserve a social and racial order upended by abolition, war, and Reconstruction. For many, Mexico offered a tabula rasa upon which to reimagine Southern identity outside the reach of Republican rule. Yet the venture was fraught from the beginning: linguistically, politically, and ideologically. The Southern colonies in Mexico would never fully flourish, and their legacy remains a largely forgotten chapter of both American and Mexican history. Here we excavate the motivations, experiences, and ultimate failures of this Confederate diaspora, situating it within the broader context of postwar memory, imperial geopolitics, and the moral dislocations of defeated ambition.

Imperial Invitations: Mexico’s Empire and the Confederate Imagination

Maximilian’s Political Gamble and the Lure of Southern Settlement

The arrival of Confederate migrants in Mexico cannot be understood apart from the imperial experiment that briefly gripped the country under Maximilian I. Backed by Napoleon III and a French army, Maximilian’s regime was installed in 1864 as an alternative to the liberal republicanism of Benito Juárez. He sought legitimacy not merely through military occupation, but through demographic transformation. European settlers, including Germans, Austrians, and Belgians, were encouraged to establish colonies that would, in theory, stabilize the empire and insulate it from liberal revolution.1

Into this strategy came the defeated Southerners. Maximilian, eager to populate his frontier regions and strengthen ties with the American South, issued imperial decrees offering generous land grants, religious tolerance, and military protection to emigrants from the former Confederacy.2 This offer appealed deeply to ex-Confederates, who saw in Mexico a place to reestablish plantations, maintain racial hierarchies, and preserve agrarian ideals without federal interference. The promise of economic autonomy and cultural continuity made the journey southward a compelling alternative to Reconstruction.

Romanticizing Empire: Southern Press and the Idea of Exile

Southern newspapers, particularly in Texas and Louisiana, began printing editorials that cast Mexico as a land of opportunity, rich in soil, light in taxation, and hospitable to “Christian gentlemen” of the Southern persuasion. These accounts frequently omitted the volatile nature of Mexico’s internal politics or the strength of Juárez’s republican forces.3 Instead, they imagined a Latin American refuge that would restore the planter’s dignity and offer a second chance at civilization.

This imperial romanticism was not without precedent. Antebellum Southerners had long looked to Latin America and the Caribbean as sites for expansion, with filibustering expeditions in Nicaragua and Cuba testifying to a tradition of extraterritorial ambition.4 The Mexican colonies after 1865 were thus not an aberration but a continuation, an attempt to relocate the geography of the slaveholding vision after its domestic defeat.

Settling the South in the South: Confederate Colonies and Daily Life

The Carlota Colony and Other Settlements

The most famous of these settlements was Carlota, located in the state of Veracruz. It was envisioned as a model community of Anglo-American agricultural self-sufficiency, led by ex-Confederate officer William H. Taliferro and others who had close ties to the old Southern elite.5 The Mexican government provided the colonists with land and logistical support, but the terrain proved difficult, the climate unfamiliar, and local resentment palpable.

Other colonies, such as those near Monterrey and in the Yucatán, were smaller and more dispersed. Many settlers quickly discovered that language barriers, logistical nightmares, and inconsistent imperial support made agricultural prosperity elusive. Promised infrastructure never materialized, and French military protection weakened as Napoleon III began withdrawing troops under pressure from the United States.6

Moreover, the ideological vision of a Southern arcadia in Mexico clashed with lived reality. Local Mexicans, already weary of imperial rule, viewed the newcomers with suspicion. The Confederate assumption that racial hierarchies would be easily transferred south of the Rio Grande ignored the complexities of Mexico’s own racial and class dynamics. As the colonies struggled to take root, the dream of transplanting the Old South abroad began to wither.

Women, Families, and the Domestic Imaginary

While much of the historiography has focused on military men and political leaders, the Confederate migration to Mexico was often familial. Women played a crucial role in attempting to recreate Southern domestic life in unfamiliar conditions. They hosted Protestant services, maintained traditional gender roles, and wrote letters home extolling, or lamenting, their new surroundings.7 These accounts reveal the emotional strain of exile, as well as the gendered expectations of rebuilding a lost civilization abroad.

Women’s writing from the colonies frequently expressed ambivalence. While some praised the land’s fertility and the hospitality of Mexican neighbors, many expressed fear, frustration, and longing for home. Their narratives form an intimate counterpoint to the public rhetoric of defiance and opportunity. The Southern household, transplanted into foreign soil, became both refuge and prison.

Collapse and Return: The End of a Southern Empire

The Fall of Maximilian and the Disillusionment of Exiles

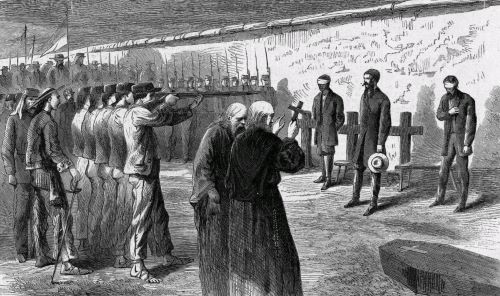

The fate of the Confederate colonies was inextricably tied to the fate of Maximilian’s empire. By 1867, French troops had withdrawn, and republican forces under Juárez recaptured Mexico City. Maximilian was executed by firing squad, and with him died the imperial protection upon which the Southern settlements had depended.8

Without political support or military security, most Confederate colonists abandoned their ventures. Some fled back to the United States, others dispersed within Mexico or sought passage to Central and South America. A few remained, assimilating into Mexican society and leaving behind hybrid cultural legacies that persisted in local memory. But for the most part, the vision of a reborn Confederacy in exile dissolved into disappointment and obscurity.

Remembering the Flight: Memory and Myth in Postwar Narratives

In the years that followed, the story of Confederate exile to Mexico became part of the broader tapestry of the “Lost Cause” mythology. It was invoked occasionally in memoirs and veterans’ reunions as a symbol of perseverance, a noble if ill-fated attempt to preserve Southern ideals. Yet it remained peripheral, too foreign, too ambiguous, too closely tied to imperial defeat and cultural dislocation.

The relative silence surrounding these episodes reflects a deeper discomfort. These migrations do not align with narratives of Southern redemption or patriotic reintegration. They suggest, instead, a willingness among some Confederates to forsake the United States altogether in pursuit of racial and social ideals no longer tenable at home. As such, they remain a haunting reminder of what the Confederacy was willing to become, and where it was willing to go, in order to survive.

Conclusion: Failed Exodus and the Fragile Geography of Defeat

The Confederate flight to Mexico was born of desperation, but also of vision, an unrepentant vision of a world in which slavery, hierarchy, and agrarian romanticism might be preserved by geography alone. It failed not only because of political miscalculation but because its very premise was flawed. Empire is never easily transplanted, and exile offers no easy soil for dreams rooted in domination.

To study this forgotten migration is to glimpse a moment in which the American South briefly looked beyond the nation it had betrayed, hoping to find in foreign empire the means to restore its own. In that hope lies the kernel of a larger tragedy: that even in defeat, the Confederacy was unwilling to reckon with its sins, preferring instead to replant them elsewhere.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Edward Shawcross, The Last Emperor of Mexico: The Dramatic Story of the Habsburg Archduke Who Created a Kingdom in the New World (New York: Basic Books, 2021), 173–175.

- Jamie Starling, “Confederates in Mexico: Lost Cause or New South Vanguard?,” Southern Spaces (January 29, 2016, https://southernspaces.org/2016/confederates-mexico-lost-cause-or-new-south-vanguard/.

- James M. McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: The South after the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 121–123.

- Robert E. May, The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire, 1854–1861 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002), 9–14.

- Terry Hulsey, “Confederates in Mexico,” Abbeville Institute Press (July 24, 2018, https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/confederates-in-mexico/.

- Thomas Mareite, Conditional Freedom: Free Soil and Fugitive Slaves from the U.S. South to Mexico’s Northeast, 1803–1861 (London: Brill, 2023), 237-250.

- Laura F. Edwards, Scarlett Doesn’t Live Here Anymore: Southern Women in the Civil War Era (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 189–191.

- Shawcross, The Last Emperor of Mexico, 309–312.

Bibliography

- Edwards, Laura F. Scarlett Doesn’t Live Here Anymore: Southern Women in the Civil War Era. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

- Hulsey, Terry. “Confederates in Mexico,” Abbeville Institute Press (July 24, 2018), https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/confederates-in-mexico/.

- Mareite, Thomas. Conditional Freedom: Free Soil and Fugitive Slaves from the U.S. South to Mexico’s Northeast, 1803–1861. London: Brill, 2023.

- May, Robert E. The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire, 1854–1861. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

- McPherson, James M. Reconstructing Dixie: The South after the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Shawcross, Edward. The Last Emperor of Mexico: The Dramatic Story of the Habsburg Archduke Who Created a Kingdom in the New World. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

- Starling, Jamie. “Confederates in Mexico: Lost Cause or New South Vanguard?.” Southern Spaces (January 29, 2016, https://southernspaces.org/2016/confederates-mexico-lost-cause-or-new-south-vanguard/.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.