Collectively, these tools chart the shifting priorities of education: from moral instruction to standardization, from vocational preparation to personalized learning.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

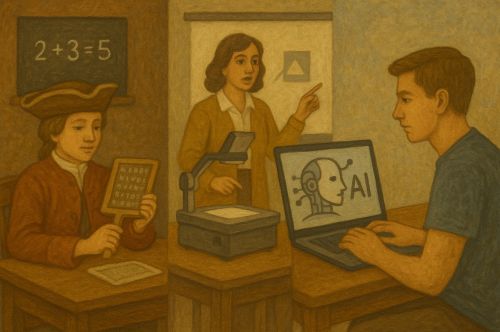

The history of education cannot be disentangled from the history of its tools. Each generation of students and teachers has been shaped not only by the ideas transmitted in classrooms but also by the technologies that mediated those ideas. From the horn-book of colonial America to today’s integration of artificial intelligence, the evolution of classroom technologies reveals a story of innovation, resistance, and adaptation. These tools were rarely neutral; they carried assumptions about pedagogy, authority, and access. What follows is a chronological exploration of classroom technology across four centuries, situating each device within its social and cultural context.

Horn-Books in the Colonial Classroom

In colonial America, education was sparse and heavily religious in content. The most iconic tool of this period was the horn-book, a wooden paddle covered by a thin, transparent sheet of animal horn that protected a printed sheet beneath. This sheet often displayed the alphabet, the Lord’s Prayer, or simple syllabaries.1 Its durability made it suitable for young children, while its compactness rendered it both portable and economical.

The horn-book symbolized an education grounded in rote learning and moral instruction. Far from an impartial device, it embodied the Puritan conviction that literacy was essential for reading Scripture, reinforcing the idea that education was primarily a tool for spiritual salvation.2

The Magic Lantern: Pictures on Walls in the 1870s

By the late nineteenth century, the classroom began to intersect with visual technologies. The Magic Lantern, an early image projector, became popular in schools in the 1870s.3 It was demonstrated at the Royal Polytechnic Institution around 1870 and dubbed “Kaleidotrope.” Using light and glass slides, teachers could project images of historical events, scientific diagrams, or faraway landscapes onto a wall or screen. This offered an unprecedented visual dimension to learning at a time when most textbooks were text-heavy and illustrations were scarce.

Although hailed as revolutionary, its use was uneven, many schools lacked electricity or the funds to maintain lantern equipment.4 Nevertheless, the Magic Lantern foreshadowed the importance of visual aids in the classroom, laying groundwork for future projection technologies.

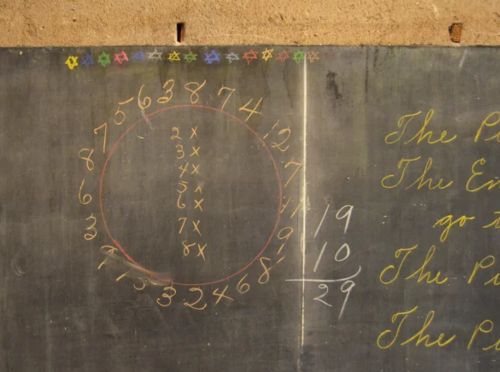

Chalkboards: Writing on Slate in the 1890s

The chalkboard, or blackboard, emerged in the nineteenth century but became ubiquitous in classrooms by the 1890s.5 This simple technology had profound implications: for the first time, teachers could present lessons to an entire class simultaneously, rather than repeating information to individuals or small groups. It facilitated interactive teaching, as students could be called to the board to solve problems or demonstrate their work. The chalkboard democratized classroom learning by making instruction more collective, though it also reinforced the centrality of the teacher as the authoritative figure at the front of the room.6 Its endurance, surviving well into the twenty-first century, speaks to its adaptability and low cost.

The Pencil: A Small Revolution in the 1900s

While chalkboards transformed teaching, the rise of the pencil in the early twentieth century revolutionized learning on an individual level. Before pencils, students often relied on ink and quills, which were messy, expensive, and impractical for children.7 The pencil, mass-produced and affordable by 1900, allowed for greater portability and erasability, fostering experimentation and self-correction.

In many ways, the pencil was a democratizing technology, opening access to literacy and numeracy for students across class lines. It also anticipated the modern emphasis on active learning, where students’ notes, sketches, and problem-solving processes became as central as the teacher’s lecture.8

Radio in the 1920s

The 1920s saw the arrival of radio as a classroom tool. Educational radio programs broadcast lessons in history, literature, and science to thousands of schools simultaneously.9 Advocates believed radio could solve the problem of teacher shortages, especially in rural areas. Some universities even created “radio classrooms,” where students gathered to listen to lectures transmitted from afar.

While the medium promised to democratize education, its impact was limited by inconsistent access to radios and resistance from teachers who feared being displaced.10 Still, radio laid the foundation for the idea of distance learning, a precursor to later online education.

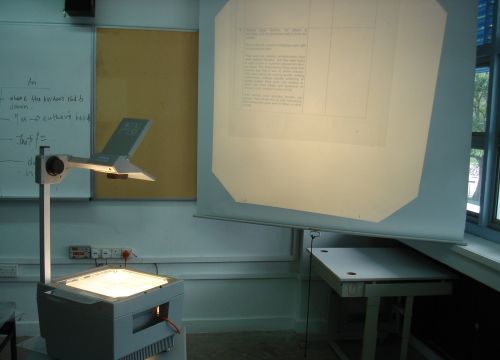

The Overhead Projector: A Supercharged Magic Lantern in the 1930s

First developed for military training during World War II, the overhead projector entered classrooms by the 1930s.11 Teachers could write on transparent sheets with markers and project the content in real time, enabling dynamic presentations. Unlike the Magic Lantern, the overhead allowed instructors to adapt material on the spot, combining prepared visuals with spontaneous annotations. The device proved especially valuable in science and mathematics classes, where diagrams and formulas could be built step by step before students’ eyes.12 Its longevity, remaining a staple into the 1990s, demonstrates its role as a bridge between analog and digital classroom technologies.

Videotapes in 1951

We’ll get to the television two sections down, but this deserves a quick mention.

With the invention of videotape in 1951, schools gained the ability to record, replay, and distribute visual content. Educational films, once limited to expensive reels, could now be easily shared. Teachers used videotapes for everything from language instruction to science documentaries.13

By offering reusable content, videotapes lightened the instructional burden on teachers while providing students with access to specialized expertise. However, critics argued that passive viewing risked reducing classroom engagement.14 The videotape epitomized mid-twentieth-century optimism about technology’s ability to standardize and disseminate knowledge.

The Skinner Teaching Machine Adapting to the 1950s

In the same period, psychologist B.F. Skinner introduced the “teaching machine,” a device grounded in behaviorist learning theory. Students worked through questions on the machine, receiving immediate feedback and reinforcement.15 Though never widely adopted, the teaching machine foreshadowed later developments in adaptive learning software and educational apps. It reflected broader mid-century anxieties about efficiency, productivity, and the possibility of mechanizing learning itself. Critics worried that the mechanistic approach stripped education of its human and creative dimensions.16

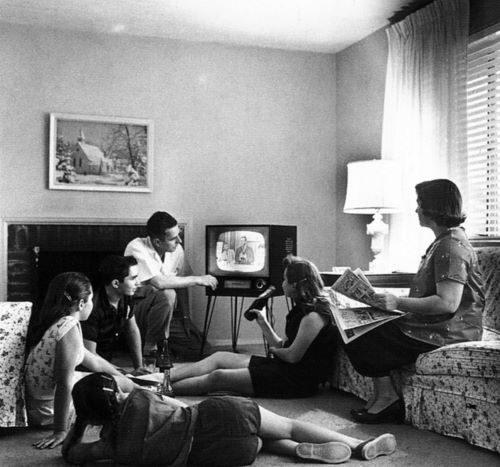

Television Hits the Scene in the 1950s

While radio introduced the spoken word into classrooms, television brought moving images and visual storytelling into the educational space. Beginning in the 1950s, school systems across the United States experimented with “instructional television,” where lessons were broadcast either live or on recorded reels to classrooms that lacked specialized teachers. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) set aside channels specifically for educational broadcasting, encouraging schools and universities to adopt the medium.17

Television was particularly effective for subjects that benefitted from visualization: science demonstrations, history reenactments, or cultural programming. Projects like the Midwest Program on Airborne Television Instruction (MPATI) in the early 1960s even beamed lessons from airplanes to schools across the Midwest.18 Despite early enthusiasm, challenges soon emerged: technical limitations, teacher resistance, and high costs made its integration uneven. By the late 1960s, television often served as a supplementary rather than central tool in education.19

Mass Reproduction and Testing: Photocopiers and Scantrons

The development of the photocopier in 1959 revolutionized the classroom by allowing teachers to reproduce worksheets, tests, and handouts cheaply and efficiently.20 This marked a shift toward the worksheet-driven pedagogy that characterized much of late twentieth-century schooling.

The Scantron machine, introduced in 1972, further mechanized education by enabling rapid grading of multiple-choice exams.21 These tools epitomized the growing emphasis on standardization, efficiency, and measurable outcomes, reflecting broader cultural trends in bureaucratization and accountability.22

Typewriters: Manual to Electric

Typewriters, both manual and later electric, played a pivotal role in shaping modern literacy instruction. By the early twentieth century, typing classes became staples in American high schools, preparing students for clerical and business careers.23

Electric typewriters, arriving in the mid-twentieth century, increased speed and reduced fatigue, solidifying typing as a necessary skill. Beyond vocational training, typewriters influenced pedagogy itself: they changed how students approached composition, emphasizing fluency and legibility over the slower, more deliberate pace of handwriting.24

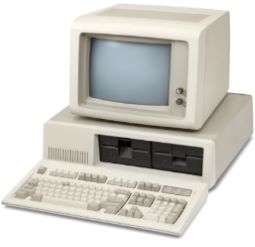

Computers Make Their Appearance

The arrival of computers in the 1970s marked a paradigm shift. Early mainframes and terminals introduced students to programming languages like BASIC, while the personal computer boom of the 1980s brought Apple IIs, Commodores, and IBM PCs into schools.25

By the 1990s, computers had become essential for word processing, research, and eventually internet access. Educational software proliferated, from math drills to immersive simulations.26

Unlike earlier technologies, computers were interactive, encouraging active problem-solving and creativity. Yet their adoption also exposed new inequities: wealthier districts could afford cutting-edge labs, while poorer schools lagged behind.27

Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) and Mobile Learning

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, handheld PDAs like PalmPilots introduced mobile learning into classrooms.28 Students used them for note-taking, scheduling, and even interactive quizzes. Though quickly overshadowed by smartphones, PDAs represented the first step toward the always-connected learner. They reflected the growing personalization of education, where learning tools became extensions of students’ individual routines rather than shared classroom devices.29

Artificial Intelligence in the Classroom Today

Today, artificial intelligence represents the latest frontier in educational technology. AI-driven tutoring systems, grading algorithms, and adaptive learning platforms personalize education to an unprecedented degree.30

Tools like ChatGPT have democratized access to knowledge, offering students instant explanations, essay drafting help, and even conversational practice in foreign languages. Yet the rise of AI also raises ethical questions: about bias, surveillance, and the role of human teachers in a world where machines can replicate aspects of pedagogy.31 As with the horn-book or chalkboard, AI is not simply a neutral tool but a cultural force reshaping what it means to teach and to learn.

Conclusion

The story of classroom technology is not one of linear progress but of continual negotiation. Each device, from horn-books to AI, was met with a mix of optimism, skepticism, and adaptation. Some, like chalkboards and pencils, became staples for generations. Others, like instructional television or teaching machines, flickered brightly before fading. Collectively, these tools chart the shifting priorities of education: from moral instruction to standardization, from vocational preparation to personalized learning. If history offers any lesson, it is that technology never determines educational outcomes on its own. Rather, it is how societies choose to integrate, resist, or repurpose these tools that defines their lasting legacy.

Appendix

Footnotes

- E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 41–44.

- Hugh Amory and David D. Hall, eds., A History of the Book in America: Volume I (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 132–135.

- Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 228–230.

- Larry Cuban, Teachers and Machines: The Classroom Use of Technology Since 1920 (New York: Teachers College Press, 1986), 17–20.

- Henry Petroski, The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance (New York: Knopf, 1990), 213–216.

- David Tyack and Larry Cuban, Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), 45–48.

- Petroski, The Pencil, 217–219.

- Russell L. Ackoff and Daniel Greenberg, Turning Learning Right Side Up: Putting Education Back on Track (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2008), 56–58.

- Cuban, Teachers and Machines, 28–31.

- Jack Schneider, From the Ivory Tower to the Schoolhouse: How Scholarship Becomes Common Knowledge in Education (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 72–74.

- Saettler, The Evolution of American Educational Technology, 152–156.

- Cuban, Teachers and Machines, 45–48.

- Watters, Teaching Machines, 89–92.

- Saettler, The Evolution of American Educational Technology, 190–193.

- B.F. Skinner, The Technology of Teaching (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1968), 23–28.

- Watters, Teaching Machines, 55–60.

- Cuban, Teachers and Machines, 64–68.

- Paul Saettler, The Evolution of American Educational Technology (Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, 1990), 213–217.

- Watters, Teaching Machines, 98–101.

- David Owen, Copies in Seconds: How a Lone Inventor and an Unknown Company Created the Biggest Communication Breakthrough Since Gutenberg (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 142–145.

- William E. Kelly, “Harnessing the River of Time,” (Journal of Employment Counseling, March 2002), 16.

- Tyack and Cuban, Tinkering Toward Utopia, 83–85.

- Charles W. Wood, The Story of the Typewriter, 1873–1923 (New York: Herkimer County Historical Society, 1923), 45–49.

- James Cortada, Before the Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, and Remington Rand and the Industry They Created, 1865–1956 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 311–315.

- Paul E. Ceruzzi, A History of Modern Computing (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998), 215–218.

- Janet Abbate, Inventing the Internet (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 142–146.

- Tyack and Cuban, Tinkering Toward Utopia, 121–123.

- Richard H. Wiggins III, “Personal Digital Assistants,” Journal of Digital Imaging 17:1 (2017), 12.

- Mark Warschauer, Laptops and Literacy: Learning in the Wireless Classroom (New York: Teachers College Press, 2006), 61–64.

- Wayne Holmes, Maya Bialik, and Charles Fadel, Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning (Boston: Center for Curriculum Redesign, 2019), 14–19.

- Neil Selwyn, Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 77–82.

Bibliography

- Abbate, Janet. Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

- Ackoff, Russell L., and Daniel Greenberg. Turning Learning Right Side Up: Putting Education Back on Track. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2008.

- Amory, Hugh, and David D. Hall, eds. A History of the Book in America: Volume I. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Ceruzzi, Paul E. A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998.

- Cortada, James. Before the Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, and Remington Rand and the Industry They Created, 1865–1956. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Cuban, Larry. Teachers and Machines: The Classroom Use of Technology Since 1920. New York: Teachers College Press, 1986.

- Holmes, Wayne, Maya Bialik, and Charles Fadel. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning. Boston: Center for Curriculum Redesign, 2019.

- Kelly, William E. “Harnessing the River of Time.” Journal of Employment Counseling 39 (2002), 12-21.

- Monaghan, E. Jennifer. Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007.

- Musser, Charles. The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Owen, David. Copies in Seconds. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

- Petroski, Henry. The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance. New York: Knopf, 1990.

- Saettler, Paul. The Evolution of American Educational Technology. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, 1990.

- Schneider, Jack. From the Ivory Tower to the Schoolhouse. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Selwyn, Neil. Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019.

- Skinner, B.F. The Technology of Teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1968.

- Tyack, David, and Larry Cuban. Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Warschauer, Mark. Laptops and Literacy: Learning in the Wireless Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press, 2006.

- Watters, Audrey. Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

- Wiggins, Richard H. III. “Personal Digital Assistants.” Journal of Digital Imaging 17: (2004), 5-17.

- Wood, Charles W. The Story of the Typewriter, 1873–1923. New York: Herkimer County Historical Society, 1923.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.