Radical Christianity in the twentieth century thus remains a testament to the enduring power, and peril, of faith when it refuses moderation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The twentieth century produced extraordinary transformations in the global landscape of religion and politics. Amid wars, revolutions, decolonization, and civil rights struggles, Christianity took on radical forms that challenged both church and state. “Radical Christianity” encompassed diverse movements: liberationist theologians who fused Marxist critique with biblical justice, pacifists who confronted militarism and nuclear war, countercultural Christians who rejected consumerism, and nationalist believers who demanded theocratic authority. While differing in aims, each embodied the conviction that Christian faith required disruptive action in the public sphere. Radical Christianity thus reshaped not only theology but the political imagination of the century.

Intellectual Roots of Radical Christianity

“God Against Culture”: The Crisis of Modernity

The devastations of the First World War discredited much of the optimistic liberal theology that had dominated the nineteenth century. Karl Barth emerged as a decisive voice against the identification of Christianity with cultural progress. In his Epistle to the Romans (1919), Barth emphasized the sovereignty of God and denounced the “cultural Christianity” that had supported nationalism and war.1 His theology set a precedent: Christianity had to resist accommodation and instead confront the social order.

The wars, the Great Depression, and the rapid secularization of the West deepened the sense that Christianity must rediscover its prophetic urgency. Many Christians rejected institutional complacency and sought radical engagement with the crises of the modern world.

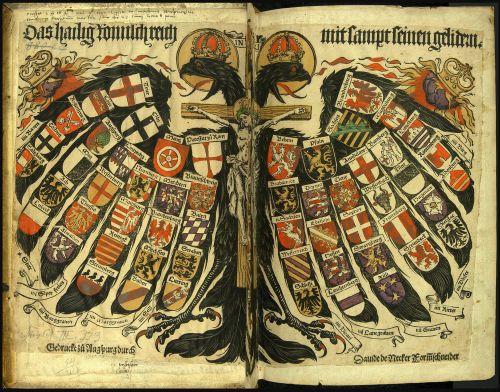

Prophets Old and New: Recovering a Radical Tradition

This radical turn drew upon earlier prophetic traditions. The abolitionist movement of the nineteenth century had already fused biblical imagery with revolutionary struggle. The Social Gospel, though moderate by later standards, taught that faith demanded transformation of social structures. These traditions gave radical Christians a vocabulary of justice and discipleship that would reemerge in more confrontational forms in the twentieth century.2

Radical Christianity and Liberation

Exodus in the Andes: Latin American Liberation Theology

In the 1960s and 1970s, Latin America produced one of the most influential radical Christian movements: liberation theology. Gustavo Gutiérrez’s A Theology of Liberation (1971) articulated a “preferential option for the poor,” insisting that God’s presence was revealed in the struggles of the oppressed.3 Drawing upon Marxist social analysis, Gutiérrez and others argued that structural injustice was sinful and demanded revolutionary transformation.

Ecclesial Base Communities, small groups of peasants studying scripture together, became the grassroots embodiment of this theology. They treated the Bible as a text of liberation, identifying with Israel’s Exodus and Christ’s proclamation of good news to the poor. The movement threatened elites and drew sharp criticism from the Vatican, but it permanently altered Catholic and Protestant theology.

“God Is Black”: Theology of Resistance in America

Across the Atlantic, Black theologians in the United States developed their own liberationist vision. James Cone’s Black Theology and Black Power (1969) declared that “God is Black,” meaning that God identifies with the oppressed Black community against white supremacy.4 Christianity, Cone argued, must empower resistance, not justify oppression.

This theology emerged within the crucible of the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of Black Power. It demanded that churches take sides, exposing the complicity of white Christianity in racism. In so doing, Black theology reframed Christian faith as inherently political, bound to the liberation of the marginalized.

Cross and Empire: Decolonial Theologies in the Global South

The end of colonial empires brought forth additional radical Christian theologies. African and Asian theologians insisted that Christianity must be disentangled from imperial domination. Figures such as Desmond Tutu in South Africa linked the Gospel to the struggle against apartheid, while Asian theologians drew upon indigenous traditions to articulate contextual theologies of liberation.5

Here too, scripture was reread as a narrative of emancipation. The Exodus became a symbol for national liberation, while Christ’s cross was seen as solidarity with the crucified peoples of history. Radical Christianity thus aligned itself with anti-colonial revolution, fusing theology with the politics of liberation.

Radical Christianity and Peace

Swords into Plowshares: Pacifist Witness

Not all radical Christianity embraced revolution. For some, the radical call of Christ lay in absolute nonviolence. Reinhold Niebuhr’s “Christian realism” rejected pacifism as naïve, but radical pacifists like A. J. Muste and Dorothy Day insisted that the Sermon on the Mount could not be compromised.6

Day’s Catholic Worker Movement, founded in 1933, practiced voluntary poverty, hospitality to the homeless, and resistance to war. Her pacifism extended even to the nuclear age, when she denounced atomic weapons as crimes against God’s creation. Radical pacifists were often marginalized, but their witness challenged the alignment of Christianity with state violence.

Prophets in Prison: The Berrigan Brothers

The Vietnam War produced some of the most dramatic examples of radical Christian pacifism. Daniel and Philip Berrigan, Jesuit priests, staged symbolic acts of resistance, including burning draft files with homemade napalm. They declared that faith demanded civil disobedience against unjust war.7

The Berrigans’ defiance scandalized both church and state but also inspired a generation of Christian activists. Their witness highlighted how radical Christianity could confront militarism not only in words but in acts of prophetic disruption.

Radical Christianity and Counterculture

The Catholic Worker: Hospitality as Revolt

The Catholic Worker Movement also embodied radical Christianity as countercultural community. By rejecting consumerism, practicing voluntary poverty, and offering hospitality houses for the destitute, the movement presented an alternative vision of Christian society. It was radical precisely because it refused integration into capitalist or nationalist frameworks.

Jesus Freaks: Evangelical Youth and the 1970s Counterculture

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Jesus People movement took root among disaffected youth. While theologically conservative, its style was radical: long-haired converts, communal living, and a rejection of mainstream consumer culture. The movement blended evangelicalism with countercultural aesthetics, embodying radical discipleship even as it remained apolitical compared to liberationist counterparts.8

Communal Experiments: Living the Early Church Today

Across denominational lines, Christian communes and intentional communities proliferated. Anabaptist groups revived radical traditions of simplicity and nonviolence, while neo-monastic movements explored forms of shared life inspired by the early church. These experiments represented radical Christianity not as protest but as alternative embodiment, living differently rather than seizing political power.

Radical Christianity and Nationalist/Theocratic Tendencies

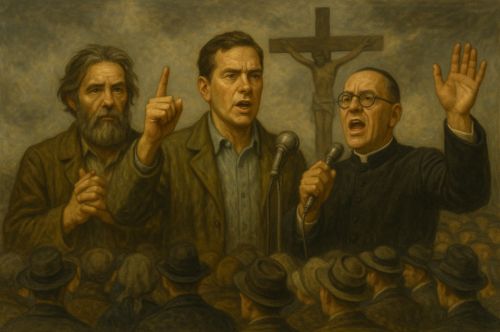

Christ and Caesar: Christian Fascism in Europe

Radical Christianity did not always lean left. In interwar Europe, some Catholic integralists and Orthodox leaders fused Christianity with authoritarian nationalism. Christianity was invoked to legitimate fascist regimes, presenting the church as the guardian of state authority. These movements were radical not in liberating the oppressed but in demanding total theocratic integration of church and state.9

“Christian America”: Evangelical Nationalism in the Cold War

In the United States, postwar evangelicalism often embraced radical nationalist rhetoric. The Cold War produced apocalyptic nationalism: premillennialists tied America’s destiny to biblical prophecy, framing the conflict with communism as a cosmic battle between God and Satan. Evangelical activists declared the U.S. a “Christian nation,” opposing secularism and pluralism in militant tones.10

Theocracy Now: Dominionist Impulses

Some strands of evangelicalism developed explicitly theocratic visions. Dominionist and Reconstructionist theologies argued that biblical law should govern civil society. While marginal, these movements embodied a radical insistence that democracy itself was insufficient without theocracy. In this vision, the radical Christian was not prophet or pacifist but lawgiver, enforcing divine rule over the nation.11

Critiques, Limits, and Contradictions

Church versus Prophet: Institutional Pushback

Radical Christianity often provoked backlash. The Vatican condemned Marxist elements of liberation theology, fearing its revolutionary potential. Protestant denominations hesitated to embrace Black and feminist theologies, wary of their confrontational politics. Radical Christianity was celebrated by activists but often marginalized by institutions.12

Radical but Not Inclusive: Gender and Sexuality

Feminist and queer theologies emerged from radical currents but frequently encountered resistance. By foregrounding women’s experience and LGBTQ identities as sites of divine revelation, they challenged both church and society. Yet their marginalization revealed the limits of radical Christianity’s inclusivity.

The Price of Success: Co-optation and Decline

Some radical movements lost their edge over time. Liberation theology, once revolutionary, became institutionalized in parts of Latin America. Countercultural communities dissolved or were absorbed into mainstream denominations. The fate of radical Christianity raised a perennial question: can radicalism survive success, or does it inevitably decline when integrated into the structures it sought to overturn?

Conclusion: The Many Faces of Radical Christianity

Radical Christianity in the twentieth century was never one thing. It included revolutionaries who fused faith with Marxism, pacifists who resisted war at great personal cost, countercultural communities that lived alternative forms of discipleship, and nationalists who sought theocratic rule. Each represented a refusal to accept the status quo, insisting that Christian faith demanded public disruption.

The legacy of these movements remains paradoxical. They revitalized Christian thought, reshaped global politics, and gave voice to the oppressed. Yet they also exposed the dangers of conflating faith with national destiny or revolutionary ideology. What unites them is their conviction that discipleship meant confrontation: whether against injustice, violence, or pluralism. Radical Christianity in the twentieth century thus remains a testament to the enduring power, and peril, of faith when it refuses moderation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, trans. Edwyn C. Hoskyns (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), 35–38.

- Christopher H. Evans, The Social Gospel in American Religion (New York: NYU Press, 2017), 41–45.

- Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1973), 67–72.

- James H. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power (New York: Seabury, 1969), 35–40.

- John Parratt, Reinventing Christianity: African Theology Today (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 92–98.

- Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness (New York: Harper, 1952), 217–220.

- Daniel Berrigan, No Bars to Manhood (New York: Doubleday, 1970), 143–147.

- Larry Eskridge, God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 201–205.

- John Pollard, Catholicism in Modern Italy: Religion, Society and Politics since 1861 (London: Routledge, 2008), 178–183.

- Kevin M. Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 211–218.

- R. J. Rushdoony, The Institutes of Biblical Law (Nutley: Craig Press, 1973), 3–9.

- Leonardo Boff, Church: Charism and Power (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1981), 101–104.

Bibliography

- Barth, Karl. The Epistle to the Romans. Translated by Edwyn C. Hoskyns. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933.

- Berrigan, Daniel. No Bars to Manhood. New York: Doubleday, 1970.

- Cone, James H. Black Theology and Black Power. New York: Seabury, 1969.

- Day, Dorothy. The Long Loneliness. New York: Harper, 1952.

- Eskridge, Larry. God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Evans, Christopher H. The Social Gospel in American Religion. New York: NYU Press, 2017.

- Gutiérrez, Gustavo. A Theology of Liberation. Maryknoll: Orbis, 1973.

- Kruse, Kevin M. One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

- Parratt, John. Reinventing Christianity: African Theology Today. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995.

- Pollard, John. Catholicism in Modern Italy: Religion, Society and Politics since 1861. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Rushdoony, R. J. The Institutes of Biblical Law. Nutley: Craig Press, 1973.

- Boff, Leonardo. Church: Charism and Power. Maryknoll: Orbis, 1981.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.