The archive is full of early alarms. The ethical question is whether we treat them only as history or also as instruction.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The story of Adolf Hitler’s ascendancy is often told as a swift descent into catastrophe. The timeline feels inevitable only in hindsight. In real time, it was a sequence of clear signals, public vows, trial balloons, and escalating tests of democratic limits that many contemporaries described, analyzed, and resisted. Their warnings were heard, then minimized, and finally dismissed as overstatement. The result was a political tragedy that unfolded in stages and in plain view.1

To take the early warnings seriously is to recognize how democratic cultures rationalize danger. Voters hope for stability. Elites gamble that power will tame the radical. Institutions assume norms will hold. Historians return to the record and find moments when a different choice remained possible. The decisive point is not that people failed to know. It is that people refused to believe.2

One pattern recurs throughout the 1920s and 1930s: the evidence of intent was published, performed, and enforced long before the worst crimes began.3

Context: Post–World War I Germany and the Seeds of Authoritarianism

Treaty of Versailles and National Humiliation

Versailles which took place in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles outside Paris. The treaty was signed by the victors of the First World War (1914-18) and the loser Germany on 28 June 1919. / Courtesy Imperial War Museum London, Wikimedia Commons

Germany’s defeat in 1918 produced a political culture saturated with loss. The Treaty of Versailles stripped territory, limited military capacity, and imposed reparations that became a moral and economic grievance. The “stab in the back” myth took root, claiming internal betrayal rather than battlefield defeat. Hitler would make this narrative a central pillar of his politics, promising national redemption and the exposure of alleged traitors.4

The myth did more than explain the past. It licensed the politics of purification. The Weimar Republic could be cast as illegitimate, its founding a capitulation to foreign diktat, its leaders objects of scorn. That interpretive frame prepared the public to see emergency measures not as violations of liberty but as necessary cures.5

Economic Collapse, Hyperinflation, and Social Unrest

By 1923, hyperinflation had destroyed savings and salaries alike. Notes with astronomical denominations could not buy a loaf of bread. Families who had trusted the state’s money lost their wealth overnight. Extremism became thinkable in such uncertainty.6

Stabilization in the mid-1920s did not erase earlier shocks. The Great Depression that began in 1929 drove unemployment to mass levels and discredited centrist coalitions that seemed unable to deliver relief. Economic despair supplied fertile ground for a politics that named enemies and promised swift, extralegal solutions.7

Weaknesses of the Weimar Republic’s Democratic Structures

The Weimar Constitution offered democratic innovations but held structural liabilities. Proportional representation produced fragmented parliaments. Presidential emergency powers under Article 48 proved dangerously elastic. Veterans’ leagues and party militias normalized street force as politics by other means.8

The constitution did not fail on paper. It failed in practice when actors used its provisions to short-circuit deliberation. The willingness to govern by decree in a crisis taught citizens to accept exceptionalism as norm. That habit would be exploited.9

The Beer Hall Putsch and the Warning Signs of Violence

The 1923 Coup Attempt

On 8–9 November 1923, Hitler and an alliance of right-wing figures attempted a coup in Munich, known as the Beer Hall Putsch. It collapsed when Bavarian authorities and the army held their line. Several people died on the Odeonsplatz. The episode revealed two points that should have remained vivid. Hitler was willing to overthrow a state government by force. He was also willing to gamble that elite allies would yield to momentum and fear.10

Hitler’s Trial and the Courtroom as Political Stage

The trial in 1924 turned peril into opportunity. Hitler used the dock as a lectern, portraying himself as a patriot rather than a criminal. Judges indulged his speeches. Reporters circulated his rhetoric across Germany. The sentence was lenient. What should have been a lesson in the cost of sedition became a proof of concept in the politics of spectacle.11

The performance mattered. It trained Hitler to convert legal jeopardy into political capital. It also taught supporters that the state could be defied without ruin, at least for someone who commanded a crowd.12

Early Warnings from Conservatives and Liberals

Conservative civil servants, Catholic politicians, and liberal journalists recorded their alarm. They described the new völkisch activism as a volatile mixture of racial mythology, leader worship, and violence. Their letters and editorials survive as documents of foresight. Yet their peers often answered with condescension. He was a provincial agitator, they said, an orator without a program, useful against the left, destined to be contained by serious men.13

Containment became a euphemism for abdication.14

Mein Kampf: Blueprint in Plain Sight

Prison Writings as Roadmap of Ideology and Ambition

Published in two volumes beginning in 1925, Mein Kampf is not an obscure text. It lays out the racial worldview, the antisemitic conspiracy theory that cast Jews as a global enemy, the fixation on propaganda, and the plan for territorial expansion in the east. It also articulates contempt for parliamentary compromises and a cult of decisive leadership. Nothing essential to later practice is absent from these pages.15

Early Readers Who Noted the Danger

Scholars, clergy, and politicians who read closely recognized the extremism. Some warned publicly that the author meant what he wrote. Others, including foreign observers, filed reports that described the book as an open declaration of intent. These warnings did not disappear. They were overwhelmed by the contrary claim that the text was too crude to be serious or too radical to be feasible.16

The Prevailing Response: Rhetoric as Exaggeration

Many educated readers dismissed the book as rant rather than doctrine. Elites assumed that coalition politics tames ideologues. They took the risk that written words would soften in the friction of governance. This cultivated disbelief became a habit that would repeat when promises turned into policies.17

Electoral Success and the Normalization of Extremism

Nazi Electoral Gains in the Late 1920s and Early 1930s

The Nazi Party remained marginal in 1928. The Great Depression altered the map. In 1930, the party jumped to 107 seats in the Reichstag. By July 1932, it was the largest party. The movement wrapped mass rallies, uniforms, and ritual into a powerful political style that merged community with obedience.18

Elections were not a rejection of democracy. They were the means of its capture. The ballot box delivered a mandate that could be repurposed as a license to hollow out the very institutions that granted it.19

Warnings from Opponents, Journalists, and Intellectuals

Social Democrats and Communists warned in their newspapers and pamphlets that fascism threatened unions, civil rights, and minorities. Liberal editors chronicled violence by party militias. International correspondents described a politics that promised national rebirth through exclusion. The evidence was abundant. The audiences were fatigued, polarized, and often more afraid of one another than of the new party on the rise.20

Conservative Elites’ Miscalculation: The Fantasy of Control

Nationalist conservatives, including President Hindenburg’s circle and men like Franz von Papen, believed they could harness Hitler. They imagined a cabinet populated by traditional right-wing figures who would hold the key ministries. The calculation was that the charisma would deliver votes and crowds while the “serious statesmen” would set policy.21

This bargain was not naïve. It was willful. Elites preferred a radical ally to a socialist rival. They valued order over pluralism. They mistook ambition for pliancy and confused popularity with dependency. Within weeks of the chancellorship, their leverage evaporated.22

Treating Rhetoric as Theater Rather Than Intent

Ordinary citizens often read Hitler’s language as performance. They heard the threat and bracketed it as exaggeration. They saw violence and explained it as excess on the fringes. People who had endured a decade of upheaval wanted a leader who would restore pride and jobs. They discounted the declared methods that would be used to achieve those ends.23

Early Governance: From Chancellor to Consolidation

Appointment as Chancellor and the Opening Moves

Hitler became chancellor on 30 January 1933 at the head of a coalition. He did not wait for a comfortable majority to act. The government sought fresh elections for March, using the campaign to intimidate rivals and flood the air with appeals to unity against alleged enemies of the nation. Police powers were reoriented toward regime priorities.24

The Reichstag Fire and Emergency Decrees

The burning of the Reichstag on 27 February 1933 supplied a pretext for sweeping restriction of civil liberties. The Reichstag Fire Decree suspended freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and privacy of communication. Arrests of Communists followed immediately. The decree did not expire. It became the framework for criminalizing dissent.25

It is important to see the mechanism. An emergency was named. A constitutional shortcut was invoked. A target group was blamed. The suspension of rights became the new baseline. People who said so at the time were accused of hysteria.26

Patterns of Repression: Targeting Communists, Socialists, and Jews

The first wave focused on the left. Offices were raided. Newspapers were closed. Union leaders were detained. Jewish lawyers and civil servants were pushed out through new rules that purported to cleanse the state. The pattern worked by increments. Each step altered expectations about what was permissible. Each new measure could be defended as a response to prior “disorder.”27

Public Reassurances and the Language of Protection

Officials spoke of protection rather than repression. They promised national renewal and moral order. They invoked culture, family, and faith. The vocabulary softened the edges of policies that removed legal protections from political enemies and minorities. This rhetoric gave cover to citizens who wished to look away.28

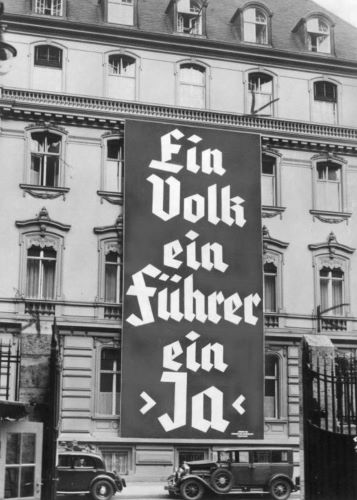

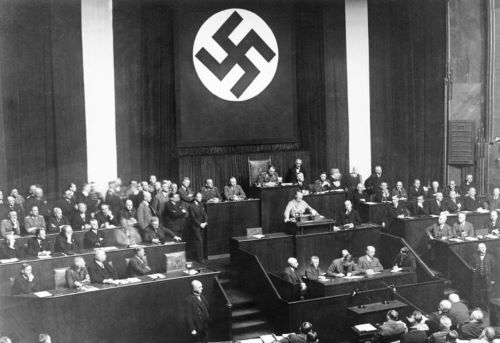

The Enabling Act and the Dissolution of the Reichstag

Legal Mechanisms that Handed Hitler Dictatorial Power

On 23 March 1933, the Reichstag passed the Enabling Act, granting the cabinet the authority to enact laws without parliamentary consent and even to deviate from the constitution. Intimidation shaped the chamber’s mood. Communists had been arrested. Some deputies voted under the gaze of uniformed men. The law was legal in form, revolutionary in effect.29

Parliamentary Voices of Resistance and Their Warnings

The Social Democratic leader Otto Wels spoke against the act, defending constitutional liberty and warning that freedom could not be bartered for promises of unity. His voice was principled and isolated. The moment shows that democracy was not voiceless. It was outnumbered and hemmed in by fear.30

Dismissing Warnings as Alarmist

Supporters of the act argued that extraordinary times required extraordinary tools. They treated civil libertarian objections as impractical, sentimental, or unpatriotic. The charge of alarmism neutralized the very vocabulary needed to describe what was happening.31

From Parliament to One-Party State

Within months, parties dissolved or were banned. By July 1933, the Nazi Party stood alone as the legal party of the state. Institutions were harmonized, professional associations reorganized, and federalism curtailed. The Reichstag became ceremonial. What had been predicted in writing and speech for years was now policy.32

Incremental Repression and the Silence of Critics

Early Concentration Camps for Political Opponents

Dachau opened in March 1933 to hold political prisoners. Camps were presented as measures to secure the public against enemies and to rehabilitate the misguided. The euphemism masked a new architecture of coercion.33

Normalization of Violence: SA, SS, and the Gestapo

Street violence by the SA had helped deliver power. The SS and Gestapo professionalized repression. Surveillance expanded. Interrogations and “protective custody” became common practices. Violence moved from the margins to the institutions of the state.34

Universities, Churches, and the Press

Universities purged Jewish and left-leaning professors. Student groups organized book burnings that dramatized the new cultural order. Churches navigated a narrow path, divided in their responses, often reluctant to confront the regime’s political sins while seeking room for pastoral life. Newspapers learned the limits of permissible criticism. Self-censorship followed.35

Exile, Emigration, and the Loss of Critical Voices

Writers, artists, jurists, and scientists left. Their exile impoverished German culture and law. Many warned from abroad that the regime’s direction was unmistakable. At home, the absence of dissent clarified what had been visible already. Silence was not neutral. It was the condition on which repression thrived.36

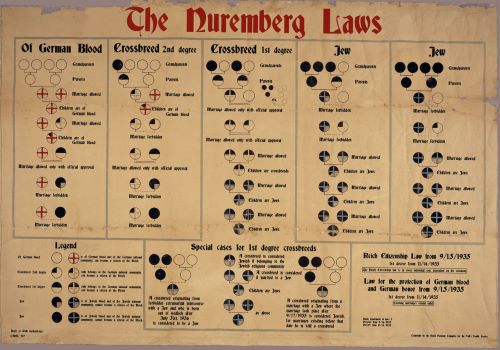

From Warnings to Reality: The Road to Genocide

Early Antisemitic Policies as Foreshadowing

From boycotts in April 1933 to the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, Jews were stripped of rights and status. Public humiliation, professional exclusion, and legal segregation advanced step by step. Officials described these as regulatory or hygienic measures. Critics identified them as the construction of a racial state. The critics were correct.37

Jewish Voices and International Critics

Jewish organizations in Germany documented assaults, legal changes, and social exclusion. International journalists filed reports. Foreign governments expressed concern. Relief efforts and emigration assistance began. The record demonstrates that people knew. The difficulty was not information. It was the willingness of outsiders to prioritize other interests over threatened lives and the reluctance of insiders to accept that the logic of policy pointed to a catastrophic end.38

Calling Warnings “Overreaction”

Many Germans insisted that the regime sought order, not annihilation. They said policy would stop at segregation. They believed that international pressure or economic rationality would impose limits. They clung to the hope that cruelty had a ceiling. That hope was not realistic.39

Realization Through Irreversibility: Kristallnacht, Ghettos, Camps

Kristallnacht in November 1938 shattered illusions. Synagogues burned. Businesses were smashed. Jews were arrested in the thousands. The violence was coordinated and public. It was a rehearsal for the far greater crimes that the war would facilitate. Once ghettos were sealed and deportations began in the east, the machinery of genocide ran with bureaucratic routine. The destination had been signaled years earlier in words and policies that many chose to discount.40

Historiographical Perspectives on Ignored Warnings

Why Contemporaries Downplayed Hitler’s Rhetoric

Historians emphasize denial, fatigue, and the normalcy bias. People who had endured inflation and unemployment wanted quiet more than justice. Elites prized order and hierarchy. Voters trusted that institutions would constrain a leader who needed their cooperation. The pattern is not uniquely German. It is human.41

Political Expediency and the Culture of Excuse

Supporters explained away each abuse as an exception. Opponents calibrated resistance to avoid greater harm. Neutral observers translated radical action into technical vocabulary. A culture of excuse replaced a culture of judgment. The cumulative effect was to make the extraordinary appear incremental.42

Comparative Frames

Scholars have compared the German case with other authoritarian ascents. The similarities include personalization of power, vilification of minorities, emergency rule, politicization of law enforcement, and capture of media and education. The variances lie in timing, ideology, and the scope of later violence. Comparative work clarifies that early warnings matter most when they are least welcomed.43

Lessons for Recognizing Early Signs in Modern Contexts

Three lessons recur. Take texts and speeches literally when they describe enemies and promised methods. Watch for the move from emergency language to permanent exception. Track the shift from party violence to state violence as a signal that repression has been institutionalized. These are not abstract cautions. They are empirical guides distilled from a specific past.44

Conclusion

From the beer hall in Munich to the vote that emptied parliament of its function, Hitler’s path was marked by declarations of intent and trials of strength. Opponents warned again and again. They were called hysterical, partisan, or naïve. The lesson is not only that they were right. It is that societies protect themselves by listening when the warnings are unwelcome. To do otherwise is to repeat the habit that turned a book into policy and a promise into a camp.

The archive is full of early alarms. The ethical question is whether we treat them only as history or also as instruction.45

Appendix

Footnotes

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2003).

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

- Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939 (New York: Knopf, 2013).

- Heinrich August Winkler, Germany: The Long Road West, Volume 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Hans Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

- Detlev J. K. Peukert, The Weimar Republic (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992).

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- Mommsen, Weimar Democracy.

- Peter Fritzsche, Germans into Nazis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (London: Odhams Press, 1952).

- Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939.

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- Kershaw, Hitler.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (Munich: Franz Eher Verlag, 1925–27).

- Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939.

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960).

- Peter Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days: When Germans Embraced the Third Reich (New York: Basic Books, 2021).

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- Kershaw, Hitler.

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- Fritzsche, Germans into Nazis.

- Ulrich Herbert, A History of Twentieth-Century Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

- Benjamin Hett, Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (New York: Penguin, 2005).

- Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days.

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power.

- Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

- Kershaw, Hitler.

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power.

- Nikolaus Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015).

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power.

- Uta Poiger, Jazz, Rock, and Rebels (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) [context on culture and control].

- Marion Kaplan, Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power.

- Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews (New York: HarperCollins, 1997–2007).

- Kershaw, Hitler.

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power.

- Fritzsche, Germans into Nazis.

- Mommsen, Weimar Democracy.

- Juan J. Linz, Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1975).

- Sheri Berman, The Primacy of Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich; Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939.

Bibliography

- Berman, Sheri. The Primacy of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Bullock, Alan. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. London: Odhams Press, 1952.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin, 2003.

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

- Fritzsche, Peter. Germans into Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Fritzsche, Peter. Hitler’s First Hundred Days: When Germans Embraced the Third Reich. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

- Herbert, Ulrich. A History of Twentieth-Century Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Hett, Benjamin. Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Munich: Franz Eher Verlag, 1925–27.

- Kaplan, Marion. Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

- Linz, Juan J. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1975.

- Mommsen, Hans. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Peukert, Detlev J. K. The Weimar Republic. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

- Poiger, Uta. Jazz, Rock, and Rebels. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960.

- Ullrich, Volker. Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939. New York: Knopf, 2013.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Winkler, Heinrich August. Germany: The Long Road West, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.