From the first shocking outbreaks in 1976 to the massive epidemic that swept through West Africa four decades later, the history of Ebola is one of both terror and transformation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

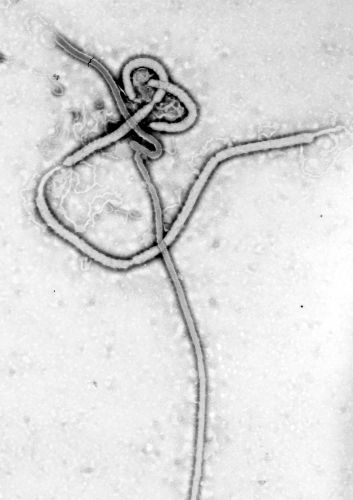

Few viruses have so forcefully impressed themselves upon both scientific discourse and the popular imagination as Ebola. Since its identification in 1976 in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Sudan, the Ebola virus has come to embody the dread of sudden, catastrophic epidemics – outbreaks marked by fever, hemorrhage, and extraordinary lethality. Yet the story of Ebola is not confined to the late twentieth century. It extends backward into fragmentary hints and parallel episodes, most notably the discovery of Marburg virus in 1967, that suggest filoviruses had been circulating silently long before Ebola acquired its name. What emerged in 1976, therefore, was not an entirely novel pathogen but the recognition of a threat that had already lingered unobserved at the interstices of human and animal populations.1

The historical significance of Ebola lies partly in its recurring drama of outbreak and containment. From the small and localized clusters in Central Africa during the 1970s and 1980s to the global alarm provoked by the West African epidemic of 2013–2016, each episode has revealed not only the biological ferocity of the virus but also the social, cultural, and political vulnerabilities of the communities it afflicts.2 Practices of caregiving and burial, the weakness of medical infrastructure, and mistrust of authorities have often amplified the spread of infection, while the very act of naming and framing the virus has shaped perceptions of Africa in the global media.3 Ebola’s history thus intertwines with questions of cultural practice, ecological disruption, and the geopolitics of global health.

Equally important is the way Ebola has served as a catalyst for scientific innovation and international cooperation. The virus became a proving ground for field epidemiology, for rapid diagnostic techniques, and eventually for the development of a vaccine, an achievement that culminated in 2019 with the approval of rVSV-ZEBOV.4 At the same time, Ebola illuminated the moral dilemmas of deploying experimental therapies under crisis conditions, exposing inequalities in access to care and the tensions between local and international priorities.5 The history of Ebola is therefore not only a narrative of microbial emergence and human suffering, but also one of scientific advance, contested ethics, and evolving frameworks of preparedness.

What follows traces the historical arc of Ebola from its pre-history in the shadows of Marburg to its emergence in 1976, its repeated return across Africa in the closing decades of the twentieth century, the epochal West African epidemic, and the more recent outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In doing so, it will highlight the virus’s entanglement with human practices, ecological change, and global systems of health governance. The aim is not merely to recount episodes of outbreak but to situate Ebola within the larger narrative of modern zoonotic disease: a story of fragile borders between species, societies, and states, continually tested by one of nature’s most devastating agents.

Pre-1976 Knowledge and Retrospective Traces

The identification of Ebola virus in 1976 did not occur in a vacuum. Rather, it was preceded by scattered accounts of diseases with hemorrhagic features in Central and West Africa, reports that only later would be revisited with the suspicion that they hinted at a filovirus presence. In the colonial medical records of the mid-twentieth century, occasional references to “acute hemorrhagic fevers” appear, though most were attributed at the time to malaria, yellow fever, or typhoid.6 Only in retrospect, once the distinctive pathology of Ebola was known, did some clinicians and historians suggest that these accounts might represent earlier, unrecognized encounters with the virus or its relatives.

A more concrete precursor came in 1967, with the sudden outbreak of Marburg virus disease among laboratory workers in Marburg and Frankfurt, West Germany, as well as in Belgrade, Yugoslavia.7 The index cases were traced to imported African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) used for polio vaccine research. Thirty-one people were infected, seven fatally.8 This episode marked the first recognition of the Filoviridae family, though the name itself had not yet been coined. The clinical syndrome (fever, rash, hemorrhage, and multiorgan failure) foreshadowed what would later be associated with Ebola. Importantly, it demonstrated that filoviruses were capable not only of causing devastating disease in Africa but also of sparking international alarm when introduced into research or medical contexts abroad.

Retrospective serological studies conducted decades later offered further evidence that Ebola was present in human and animal populations well before 1976. Surveys of preserved blood samples from the 1960s in Sudan and the Ivory Coast revealed antibodies consistent with exposure to Ebola-like viruses.9 Although the interpretation of such data remains contested, the findings suggest a silent circulation of the pathogen in both forest and savanna ecosystems. These results dovetail with ecological observations pointing to bats, particularly fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family, as likely reservoirs, capable of maintaining the virus asymptomatically and transmitting it intermittently to other species.10

Such evidence reinforces the notion that 1976 was not the origin but rather the moment of recognition. The sudden convergence of ecological, social, and medical conditions (hospital practices, ecological disturbances, and globalizing networks of public health surveillance) brought Ebola into visibility. In that sense, the virus’s “birth” in human history resembles that of many zoonotic pathogens: a presence long unrecognized until ecological or epidemiological accidents forced it into the medical record.

The First Identified Outbreaks (1976)

The year 1976 marked the dramatic entrance of Ebola virus onto the stage of global health. Two nearly simultaneous outbreaks, one in northern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and the other in southern Sudan, alerted the international community to a previously unknown hemorrhagic fever. Though separated by more than a thousand kilometers, both episodes shared striking clinical features and high case fatality rates, yet they also displayed distinctive epidemiological patterns that underscored the complexity of the virus’s behavior.11

In Yambuku, a mission hospital in Zaire, the first recognized cases appeared in late August.12 The outbreak spread rapidly within the hospital environment, facilitated by the reuse of inadequately sterilized needles and syringes, a common practice in resource-limited medical settings.13 Approximately 318 cases were recorded, with a staggering fatality rate of nearly 90 percent.14 The epidemic’s intensity prompted the dispatch of international teams, including experts from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control, who identified a novel filovirus under electron microscopy and subsequently named it “Ebola virus” after a nearby river.15

Meanwhile, in Nzara, Sudan, a separate outbreak unfolded. Here the initial infections appeared among workers in a cotton factory, suggesting a possible zoonotic introduction through bats or other animals inhabiting the surrounding environment.16 The outbreak involved 284 cases, with a fatality rate of about 53 percent, significantly lower than in Zaire, though still devastating.17 This strain, later classified as Sudan virus, was genetically distinct from the Zairean isolate, inaugurating the recognition of multiple species within the Ebola genus.

The near-simultaneity of these two outbreaks raised urgent questions about the ecology of the virus: Was Ebola newly emergent, or had it circulated undetected in animal reservoirs for decades? Why did the Zairean outbreak burn with such ferocity within a hospital setting, while the Sudanese outbreak appeared more connected to workplace and community exposures? The very act of investigation produced insights that would shape the trajectory of Ebola research: the recognition of zoonotic origins, the dangers of unsafe medical practices, and the necessity of rapid, coordinated international response.

The naming of the virus after the Ebola River in Zaire was itself a symbolic gesture, meant to dissociate the new disease from the stigmatization of Yambuku village.18 Yet this choice also reflected the power of geography in the global imagination of disease. From its inception, Ebola was framed not only as a medical problem but as a phenomenon rooted in the African landscape, a framing that would influence both research priorities and the cultural narratives surrounding the virus in decades to come.

Outbreaks in the 1980s–1990s

Following the dual outbreaks of 1976, Ebola seemed to vanish almost as suddenly as it had appeared. Yet the respite proved temporary. In 1979, the virus re-emerged in Nzara, Sudan, the same region affected just three years earlier.19 This second Sudanese outbreak was smaller, involving thirty-four cases and twenty-two deaths, but it demonstrated that Ebola was not a one-time anomaly. The persistence of the virus in the same geographic zone suggested the presence of a stable reservoir, even if its identity remained elusive.20

For nearly two decades, no confirmed Ebola outbreaks were reported, fostering a sense of uneasy dormancy. Then, in the mid-1990s, the virus erupted once more, this time in Gabon and Zaire. In 1994, an outbreak in Minkébé, Gabon, caused thirty-two deaths and was linked to contact with a dead chimpanzee, highlighting the role of primates as intermediate hosts in the chain of transmission.21 That same year, a Swiss researcher became infected while performing a necropsy on a chimpanzee in Côte d’Ivoire.22 This was the first documented case of Ebola infection in a non-African scientist and underscored the occupational hazards faced by field researchers working at the human–animal interface.

In 1995, Kikwit, Zaire, became the site of a devastating epidemic.23 More than 300 people died in an outbreak marked by widespread community transmission and the involvement of healthcare workers. International response teams, again coordinated by the WHO and CDC, deployed containment strategies of patient isolation, barrier nursing, and contact tracing, methods that would become the standard toolkit for Ebola control.24 The Kikwit epidemic also received significant global media attention, introducing Ebola to the broader public consciousness as a synonym for viral terror.

Further outbreaks followed in Gabon between 1996 and 1997, with mortality rates exceeding 70 percent. These events were frequently linked to hunting and butchering of wildlife, particularly gorillas and chimpanzees found dead in the forest.25 Such episodes reinforced the ecological dimension of Ebola’s history: human outbreaks were often the end point of chains that began with viral circulation among bats and spillover into primate populations, before cascading into local communities.

By the close of the 1990s, the pattern was unmistakable. Ebola was not an isolated curiosity but a recurring presence in Central Africa, capable of igniting epidemics when ecological disturbance, human practices, and weak healthcare infrastructures converged. The virus’s unpredictability, combined with its high lethality, gave it a reputation as a biological menace waiting in the shadows, an image that shaped scientific research agendas, policy discussions, and popular fears as the twenty-first century approached.

The Early 2000s: Expanding Knowledge and Recurring Outbreaks

The opening years of the twenty-first century revealed that Ebola was not confined to the dramatic flare-ups of the 1990s but had become a recurrent threat across multiple regions of sub-Saharan Africa. In 2000, northern Uganda experienced the largest outbreak to date in the district of Gulu.26 With over 400 cases and more than 200 deaths, this episode represented a new phase in the history of the virus. The Ugandan government, in collaboration with the World Health Organization and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), mounted an unprecedentedly large and coordinated response.27 For the first time, systematic measures of case isolation, contact tracing, and public communication were implemented at scale, laying the foundation for modern Ebola containment strategies.

The Gulu outbreak also highlighted the human cost borne by healthcare workers. Dozens of nurses and physicians contracted the virus, many fatally, in the course of treating patients.28 Their sacrifices underscored the need for improved protective protocols and sufficient resources, needs that would remain pressing in later epidemics. At the same time, the Ugandan epidemic catalyzed advances in laboratory diagnostics: mobile field laboratories capable of confirming Ebola cases within hours were deployed, reducing reliance on distant reference labs and accelerating containment efforts.29

In Côte d’Ivoire, a separate episode in 1994 had already signaled the occupational hazards faced by researchers. A Swiss ethologist contracted Ebola after performing a necropsy on a chimpanzee from the Taï Forest and survived following treatment in Switzerland.30 Though limited to a single case, this incident was the first documented infection with what came to be known as Taï Forest virus, further diversifying the taxonomy of the genus. It also made starkly visible the ecological risks of fieldwork in areas where humans and wildlife overlap.

Recurring outbreaks in Gabon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the early 2000s reinforced the perception of Ebola as a virus capable of reappearing without warning. Many of these episodes were linked to the hunting and consumption of bushmeat, particularly gorillas and chimpanzees, whose mass die-offs often preceded human cases.31 The virus thus became not only a public health issue but also a conservation concern, contributing to the decline of endangered great apes.

By the close of the first decade of the 2000s, Ebola had established itself as a virus of both medical and ecological significance. It was no longer perceived merely as a rare curiosity of Central Africa but as a recurring zoonotic hazard requiring international vigilance. Scientific progress had been made in understanding reservoirs, developing diagnostics, and improving outbreak response, yet the virus’s capacity to spark sudden and lethal epidemics remained undiminished. The stage was set for the crisis that would define Ebola’s global reputation in the twenty-first century: the West African epidemic of 2014–2016.

The West African Epidemic (2013–2016)

The largest and most consequential Ebola outbreak in history began in December 2013 in a small village in southeastern Guinea.32 A two-year-old child, later identified as the index case, developed fever and died, followed soon after by several family members. For weeks, the illness spread silently across rural communities before reaching urban centers and national borders. By the time the epidemic was officially recognized in March 2014, the virus had already seeded itself in Liberia and Sierra Leone, setting in motion a regional catastrophe.33

Unlike previous outbreaks, which were largely confined to remote forested areas, the West African epidemic penetrated cities.34 Dense urban populations, fragile health systems, and porous borders allowed Ebola to spread with unprecedented speed and scale. Over the course of two years, more than 28,000 cases were reported and over 11,000 people died.35 The epidemic overwhelmed local hospitals, shuttered economies, and left behind a trail of social disruption and stigma that outlasted the virus itself. Families were torn apart not only by mortality but also by the fear that survivors and caregivers might still harbor infection.

International response unfolded slowly, and in the early months, global institutions underestimated the scale of the crisis.36 It was not until the virus threatened to engulf Monrovia and Freetown that the United Nations, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Médecins Sans Frontières began to coordinate massive intervention efforts. The deployment of foreign medical staff, the construction of Ebola treatment units, and eventually the mobilization of military resources reflected both the gravity of the situation and the degree to which Ebola had become a global security concern.

The epidemic also accelerated the development and testing of experimental therapies and vaccines. Most significant was the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, which was fast-tracked through clinical trials in Guinea under a “ring vaccination” strategy in 2015.37 Its success, later confirmed in larger studies, marked one of the most important breakthroughs in the history of filoviruses. At the same time, ethical debates raged about the use of untested drugs, the prioritization of Western aid workers for scarce experimental treatments, and the unequal distribution of medical resources between local populations and international staff.38

The West African epidemic transformed Ebola from a sporadic regional outbreak into a crisis with global implications. Images of health workers in protective suits, mass burials, and frightened urban populations became iconic representations of epidemic vulnerability in the twenty-first century. Ebola had entered not only the annals of medical history but also the collective consciousness of a world suddenly aware that pathogens emerging in remote forests could destabilize entire regions and threaten international order.

Post-2016 Developments

The conclusion of the West African epidemic in 2016 did not mark the end of Ebola’s story. Rather, it ushered in a new phase defined by recurrent flare-ups, ongoing ecological mysteries, and the integration of the virus into global health preparedness frameworks. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), multiple outbreaks occurred between 2017 and 2020, demonstrating that the virus remained entrenched in its Central African heartland.39 The North Kivu and Ituri outbreaks of 2018–2020 proved especially challenging: they occurred in conflict zones marked by political instability, widespread displacement, and violence against health workers.40 Unlike earlier episodes, these outbreaks required not only epidemiological expertise but also negotiation with armed groups and the navigation of deep community mistrust.

The availability of a vaccine for the first time in Ebola’s history significantly altered the trajectory of these later outbreaks. In 2019, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine received regulatory approval, following its successful deployment under “compassionate use” protocols during the DRC outbreaks.41 More than 300,000 people were vaccinated in the course of those emergencies, and the use of ring vaccination demonstrated that immunization could decisively curtail chains of transmission. This milestone represented a historic achievement: Ebola, long seen as an unstoppable force, could now be prevented.

At the same time, renewed questions emerged about Ebola’s long-term ecology and persistence. Cases of viral relapse in survivors years after initial infection raised the possibility of chronic reservoirs within human hosts, complicating assumptions about epidemic closure.42 Survivors also reported ongoing medical and psychological sequelae, from joint pain to stigma, underscoring that Ebola’s burden does not end when an outbreak is declared over.43

In global health discourse, the post-2016 period marked a turning point. Ebola became a template for epidemic preparedness, cited in discussions of pandemic response when COVID-19 emerged in 2020.44 The infrastructures created during the West African crisis (laboratories, rapid deployment teams, community engagement strategies) were redeployed for coronavirus response, reflecting Ebola’s lasting influence on global health systems. Yet the memory of delayed international mobilization in 2014 also haunted the early months of COVID-19, serving as a reminder that political will often lags behind epidemiological necessity.

In the years following 2016, Ebola transitioned from a terrifying unknown to a managed but persistent threat. It is no longer imagined solely as an African catastrophe but as a global disease whose lessons about surveillance, trust, and scientific innovation reverberate far beyond the regions where the virus itself continues to smolder.

Broader Themes

The recurring history of Ebola illuminates broader questions that transcend virology. At its core, Ebola is a zoonotic disease, arising from the fragile boundaries between human communities and animal reservoirs. The identification of bats as likely hosts underscores how ecological disruption: deforestation, mining, agricultural expansion, creates conditions for viral spillover.45 Each outbreak has traced a path back to human encroachment upon forest ecologies, reminding us that emerging infectious diseases are not isolated accidents but consequences of environmental change.

The virus also exposes the intimate intersection of biology and culture. Funeral practices, caregiving traditions, and communal forms of reciprocity, acts rooted in dignity and solidarity, have often become sites of transmission.46 Efforts to control outbreaks frequently clashed with these cultural norms, generating resistance to health interventions and mistrust of both local authorities and international responders. In West Africa, for instance, attempts to impose cremation or to prevent families from touching the bodies of the dead were perceived as assaults on cultural identity.47 The success of later interventions depended not simply on biomedical strategies but on partnerships that respected and incorporated community knowledge.

Ebola’s history further highlights the inequalities of global health infrastructure. The virus’s lethality drew international attention, but the pattern of delayed mobilization, especially in 2014, revealed how crises in the Global South often struggle to command urgency until they are perceived as threats to the Global North.48 The unequal access to experimental therapies, where foreign healthcare workers were prioritized over local patients, remains a stark reminder of enduring hierarchies in medical ethics.49

At the same time, Ebola has served as a crucible for scientific and institutional innovation. The establishment of mobile diagnostic laboratories, the development of ring vaccination strategies, and the integration of rapid response units into the World Health Organization’s framework all represent lasting contributions to the field of epidemic preparedness.50 Ebola thus stands not only as a history of tragedy but also as a record of evolving knowledge, cooperation, and adaptation.

In the broader historical arc of emerging infectious diseases, Ebola exemplifies the dual reality of global interconnectedness: pathogens once confined to remote ecologies can threaten entire continents, while the response to such threats increasingly depends upon international solidarity and scientific exchange. The history of Ebola is therefore not solely about a virus; it is about the vulnerabilities and capacities of humanity in an age where the boundaries between local and global, natural and social, are constantly tested.

Conclusion

From the first shocking outbreaks in 1976 to the massive epidemic that swept through West Africa four decades later, the history of Ebola is one of both terror and transformation. The virus, long invisible in animal reservoirs, has erupted episodically into human populations, leaving behind trails of death, fear, and social rupture. Each outbreak has illuminated the precarious relationship between human societies and their environments, revealing how fragile infrastructures, cultural practices, and political neglect can turn viral emergence into catastrophe.51

Yet Ebola’s history is also a chronicle of resilience and discovery. The virus compelled the creation of new methods of field epidemiology, spurred innovations in diagnostics and treatment, and accelerated the development of one of the fastest vaccines ever brought to approval.52 It has forced the international community to confront uncomfortable ethical questions about equity, trust, and the responsibilities of wealthy nations in moments of crisis. In this sense, Ebola has been both a scourge and a teacher: exposing weaknesses in global health systems while offering lessons that extend into the era of COVID-19 and beyond.

As with many zoonotic diseases, the story of Ebola is unfinished. The virus continues to smolder in the forests of Central Africa, reappearing in sudden flare-ups that remind the world of its persistence. Survivors live with both medical sequelae and social stigma, bearing witness to the long shadows epidemics cast even after the last case is declared.53 The legacy of Ebola lies not only in the mortality it has inflicted but also in the infrastructures it has reshaped, the solidarities it has tested, and the questions it continues to raise about humanity’s place in a changing ecological and political order.

In the final measure, Ebola belongs to the broader narrative of modern epidemic history: a reminder that the boundaries between human and nonhuman worlds are porous, that global health security is fragile, and that vigilance, humility, and equity must guide the responses to future microbial threats. To write the history of Ebola is therefore to write a cautionary tale about the entanglements of life and death in a world where the next outbreak is never entirely unexpected.

Appendix

Footnotes

- K. M. Johnson, et al. “Evidence for Occurrence of Filovirus in Humans and Imported Monkeys,” Medical Microbiology and Immunology 181 (1992): 43-55.

- Piot, P., No Time to Lose: A Life in Pursuit of Deadly Viruses (New York: Norton, 2012), 33–35.

- Hewlett, B. S., and R. P. Amola, “Cultural Contexts of Ebola in Northern Uganda,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 9, no. 10 (2003): 1242–48.

- Feldmann, H., and T. W. Geisbert, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever,” The Lancet 377, no. 9768 (2011): 849–62.

- Calain, P., “Ethics and Images of Suffering Bodies in Humanitarian Medicine,” Social Science & Medicine 63, no. 2 (2006): 376–88.

- Pattyn, S., ed., Ebola Virus Haemorrhagic Fever (Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press, 1978), 3–6.

- Martini, G. A., and R. Siegert, Marburg Virus Disease (Berlin: Springer, 1971), 8–10.

- Siegert, R., et al., “On the Etiology of an Unknown Human Infection,” Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 92 (1967): 2341–46.

- Le Guenno, B., et al., “Isolation and Partial Characterization of a New Strain of Ebola Virus,” The Lancet 345 (1995): 1271.

- Leroy, E. M., et al., “Fruit Bats as Reservoirs of Ebola Virus,” Nature 438 (2005): 575–76.

- Johnson et al., “Isolation and Partial Characterization,” 569.

- Piot, No Time to Lose, 38.

- Pattyn, Ebola Virus Haemorrhagic Fever, 14.

- WHO, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever in Zaire, 1976,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 56 (1978): 271–93.

- Pattyn, Ebola Virus Haemorrhagic Fever, 18.

- WHO, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever in Sudan, 1976,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 56 (1978): 247–70.

- Ibid.

- Piot, No Time to Lose, 41.

- WHO, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever in Sudan, 1979,” Weekly Epidemiological Record 54 (1979): 345–47.

- Feldmann and Geisbert, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever,” 851.

- Georges, A. J., et al., “Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreaks in Gabon, 1994,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 175, Suppl 1:S65-75 (1999).

- Le Guenno et al., “Isolation and Partial Characterization,” 1271.

- Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J., et al., “Ebola Outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 179 (1999): S1–7.

- Ibid.

- Leroy, E. M., et al., “Multiple Ebola Virus Transmission Events and Rapid Decline of Central African Wildlife,” Science 303, no. 5656 (2004): 387–90.

- Okware, S. I., et al., “An Outbreak of Ebola in Uganda,” Tropical Medicine & International Health 7, no. 12 (2002): 1068–75.

- Hewlett and Amola, “Cultural Contexts,” 1242–43.

- Okware et al., “An Outbreak of Ebola in Uganda,” 1070.

- Feldmann and Geisbert, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever,” 854.

- Le Guenno et al., “Isolation and Partial Characterization,” 1272.

- Leroy et al., “Multiple Transmission Events,” 387.

- Baize, S., et al., “Emergence of Zaire Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea,” New England Journal of Medicine 371 (2014): 1418–25.

- WHO, “Ebola Virus Disease—Guinea,” Disease Outbreak News (March 2014).

- Baize et al., “Emergence of Zaire Ebola Virus,” 1420.

- WHO, “Ebola Situation Report” (2016).

- Moon, S., et al., “Will Ebola Change the Game? Ten Essential Reforms before the Next Pandemic,” The Lancet 386, no. 10009 (2015): 2204–21.

- Henao-Restrepo, A. M., et al., “Efficacy and Effectiveness of an rVSV-Vectored Vaccine in Preventing Ebola Virus Disease,” New England Journal of Medicine 377 (2017): 372–82.

- Calain, “Ethics and Images,” 377.

- WHO, “Ebola Virus Disease—Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Disease Outbreak News (2018–2020).

- Ilunga Kalenga, O., et al., “The Ongoing Ebola Epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2018–2019,” New England Journal of Medicine 381 (2019): 373–83.

- Henao-Restrepo et al., “Efficacy and Effectiveness,” 375.

- Jacobs, M., et al., “Late Ebola Virus Relapse Causing Meningoenchephalitis: A Case Report,” The Lancet 388 (2016): 498.

- James, P. B., et al., “Ebola Survivors and Stigma in Sierra Leone,” BMC Public Health 20 (2020): 182.

- Moon et al., “Will Ebola Change the Game?” 2205.

- Leroy et al., “Fruit Bats as Reservoirs,” 575.

- Hewlett and Amola, “Cultural Contexts,” 1244.

- Ibid.

- Moon et al., “Will Ebola Change the Game?” 2206.

- Calain, “Ethics and Images,” 379.

- Feldmann and Geisbert, “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever,” 856.

- Piot, No Time to Lose, 212.

- Henao-Restrepo et al., “Efficacy and Effectiveness,” 376.

- James et al., “Ebola Survivors and Stigma,” 185.

Bibliography

- Baize, S., et al. “Emergence of Zaire Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea.” New England Journal of Medicine 371 (2014): 1418–25.

- Calain, P. “Ethics and Images of Suffering Bodies in Humanitarian Medicine.” Social Science & Medicine 63, no. 2 (2006): 376–88.

- Feldmann, H., and T. W. Geisbert. “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever.” The Lancet 377, no. 9768 (2011): 849–62.

- Georges, A. J., et al. “Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreaks in Gabon, 1994.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 179, Suppl 1:S65-75 (1999).

- Henao-Restrepo, A. M., et al. “Efficacy and Effectiveness of an rVSV-Vectored Vaccine in Preventing Ebola Virus Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine 377 (2017): 372–82.

- Hewlett, B. S., and R. P. Amola. “Cultural Contexts of Ebola in Northern Uganda.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 9, no. 10 (2003): 1242–48.

- Ilunga Kalenga, O., et al. “The Ongoing Ebola Epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2018–2019.” New England Journal of Medicine 381 (2019): 373–83.

- Jacobs, M., et al. “Late Ebola Virus Relapse Causing Meningoenchephalitis: A Case Report.” The Lancet 388 (2016): 498.

- James, P. B., et al. “Ebola Survivors and Stigma in Sierra Leone.” BMC Public Health 20 (2020): 182.

- Johnson, K. M., et al. “Evidence for Occurrence of Filovirus in Humans and Imported Monkeys.” Medical Microbiology and Immunology 181 (1992): 43-55.

- Le Guenno, B., et al. “Isolation and Partial Characterization of a New Strain of Ebola Virus.” The Lancet 345 (1995): 1271.

- Leroy, E. M., et al. “Fruit Bats as Reservoirs of Ebola Virus.” Nature 438 (2005): 575–76.

- Leroy, E. M., et al. “Multiple Ebola Virus Transmission Events and Rapid Decline of Central African Wildlife.” Science 303, no. 5656 (2004): 387–90.

- Martini, G. A., and R. Siegert. Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin: Springer, 1971.

- Moon, S., et al. “Will Ebola Change the Game? Ten Essential Reforms before the Next Pandemic.” The Lancet 386, no. 10009 (2015): 2204–21.

- Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J., et al. “Ebola Outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 179 (1999): S1–7.

- Okware, S. I., et al. “An Outbreak of Ebola in Uganda.” Tropical Medicine & International Health 7, no. 12 (2002): 1068–75.

- Pattyn, S., ed. Ebola Virus Haemorrhagic Fever. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press, 1978.

- Piot, P. No Time to Lose: A Life in Pursuit of Deadly Viruses. New York: Norton, 2012.

- Siegert, R., et al. “On the Etiology of an Unknown Human Infection.” Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 92 (1967): 2341–46.

- World Health Organization. “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever in Zaire, 1976.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 56 (1978): 271–93.

- World Health Organization. “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever in Sudan, 1976.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 56 (1978): 247–70.

- World Health Organization. “Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever in Sudan, 1979.” Weekly Epidemiological Record 54 (1979): 345–47.

- World Health Organization. “Ebola Situation Report.” Geneva: WHO, 2016.

- World Health Organization. “Ebola Virus Disease—Guinea.” Disease Outbreak News. March 2014.

- World Health Organization. “Ebola Virus Disease—Democratic Republic of the Congo.” Disease Outbreak News, 2018–2020.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.