The evangelical takeover of the Republican Party was not a sudden rupture but the culmination of decades of social, cultural, and political transformations.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Republican Party of the mid-twentieth century bore little resemblance to the coalition that emerged by the 1980s under the leadership of Ronald Reagan. Once anchored by a northeastern establishment of business elites and moderate Protestants, the GOP was transformed into the political home of conservative evangelicals, who came to define its cultural and electoral base. This profound realignment, often described as part of the broader “Great Reversal” of the American party system, did not occur overnight. It was the product of intersecting forces (civil rights backlash, cultural upheaval, and religious mobilization) that took place over decades beginning around the 1930s, converged most powerfully in the 1970s, and crystallized in the 1980 election of Reagan with the support of the newly formed Moral Majority.

Historians have long debated the origins of this evangelical ascendancy. Frances FitzGerald has emphasized the persistence of a distinct evangelical subculture that, once awakened to politics, dramatically reshaped the national landscape.1 Kevin Kruse has shown how corporate and religious interests fused as early as the 1950s to craft a rhetoric of “Christian America,” preparing the ideological terrain for later mobilization.2 Daniel K. Williams traces the trajectory more directly, contending that evangelicals entered Republican politics less from sudden moral panic over abortion or school prayer than from long-standing concerns about race, local control, and social authority.3 This revisionist strand of scholarship challenges the popular myth that Roe v. Wade (1973) alone galvanized the religious right. Instead, it highlights battles over desegregation and federal regulation of private Christian academies, such as the Bob Jones University tax-exemption case, as central catalysts.4

By the late 1970s, evangelical leaders such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Francis Schaeffer forged a movement that defined itself against secular liberalism, feminism, and gay rights, while finding a willing partner in the Republican Party. President Jimmy Carter, himself a self-professed born-again Christian, initially attracted evangelical voters but soon disappointed them with his perceived lukewarmness on abortion and school prayer. Reagan, in contrast, signaled clear solidarity, famously telling a gathering of evangelical leaders, “I know you can’t endorse me, but I endorse you.”5 This moment epitomized the merger of evangelical identity with partisan politics, cementing the GOP’s transformation into a party of cultural conservatism grounded in religious conviction.

The evangelical takeover of the Republican Party was not simply a matter of electoral strategy; it represented a profound reorientation of American political culture. By turning religious belief into a vehicle for partisan mobilization, the GOP and its evangelical allies reshaped the contours of debate over constitutional rights, public morality, and the meaning of democracy itself. What follows examines the evangelical ascendancy from the party realignments of the 1960s through the Reagan era, arguing that it marked both the culmination of long-standing grievances and the beginning of a new political order in which the boundaries between faith and politics became inextricably blurred.

The Great Reversal: From Democratic South to Republican Stronghold

Overview

For much of American history, white evangelical Protestants in the South were loyal Democrats. The “Solid South” of the mid-twentieth century was held together by a peculiar alliance: white supremacy as the foundation of Democratic dominance, coupled with a strong evangelical Protestant moral culture. Yet, by the late twentieth century, these same constituencies had become the backbone of the Republican Party. Understanding how and why this reversal occurred is crucial to tracing the evangelical takeover of the GOP.

From the Solid South to Political Fracture

The Democratic Party’s long hold on the South began to fray under the pressures of the civil rights movement. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented turning points. President Lyndon Johnson, upon signing the Civil Rights Act, reportedly told an aide, “We have lost the South for a generation.”6 His assessment proved prescient: white Southerners, many of them devout evangelicals, felt betrayed by the national Democratic Party’s embrace of racial equality.

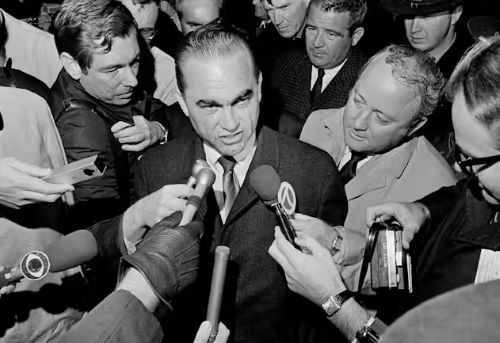

Prominent segregationist politicians such as George Wallace, Strom Thurmond, and Lester Maddox capitalized on this discontent. Wallace’s 1968 presidential campaign, though technically independent, drew enormous evangelical support in the South, fusing opposition to civil rights with a populist moral rhetoric.7 Thurmond’s defection to the Republican Party in 1964 foreshadowed a broader exodus, signaling that the GOP would welcome disaffected white Southerners.

Nixon and the Southern Strategy

The figure most associated with consolidating these shifts was Richard Nixon. His so-called “Southern Strategy” appealed to white resentment in coded, racially neutral terms; they emphasized “law and order,” “states’ rights,” and resistance to federal overreach. Though Nixon did not openly court evangelicals on cultural grounds, his administration laid the foundation for their later migration by recasting the Republican Party as the defender of traditional authority against federal liberalism.8

Barry Goldwater’s earlier campaign in 1964 had already revealed this potential. Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act not out of overt racism, he argued, but on grounds of limited government and constitutional principle. Evangelicals and segregationists alike embraced this stance, seeing in it a defense of their autonomy against what they perceived as creeping federal intrusion.9 Goldwater’s landslide defeat nevertheless planted the seeds of a conservative coalition that would flower in the 1980s.

Evangelical Cultural Unease

Beyond civil rights, evangelicals increasingly saw federal power as hostile to their values. Desegregation of public schools was followed by scrutiny of private Christian academies, many of which had arisen in the South as “segregation academies” after Brown v. Board of Education. When the Internal Revenue Service threatened to revoke the tax-exempt status of racially discriminatory schools in the 1970s, evangelicals viewed the action as a direct attack on their religious liberty. The most famous case was Bob Jones University, which lost its tax-exempt status in 1976 for banning interracial dating among students.10

While the later narrative of the Christian Right often foregrounded abortion or school prayer, historians such as Randall Balmer and Daniel K. Williams argue that resistance to federal regulation of Christian education was the true spark that ignited evangelical political mobilization.11 For many conservative believers, the defense of their institutions against Washington bureaucrats resonated more powerfully than abstract legal debates over reproductive rights.

Thus, by the mid-1970s, the stage was set. Evangelicals, once scattered across both parties and often politically disengaged, had come to view the Democratic Party as an enemy of their cultural world. The Republican Party, increasingly defined by opposition to federal intervention, emerged as their natural home. This transition (rooted in racial politics, institutional defense, and cultural unease) formed the necessary prelude to the evangelical surge of the Reagan era.

The Evangelical Awakening of the 1970s

Overview

The cultural and political turbulence of the 1970s provided the crucible in which evangelical activism was transformed from a scattered movement into a coherent political force. While evangelicals had long been a major cultural presence in American life, their mobilization into explicitly partisan politics was relatively new. During this decade, disillusionment with liberal policies, combined with catalytic cultural flashpoints, pushed evangelicals out of the pews and into the political arena.

Billy Graham and Mainstream Evangelicalism

For decades, Billy Graham represented the public face of evangelical Christianity. His sprawling crusades, national radio and television presence, and close ties to presidents from Truman through Nixon made him one of the most influential religious figures of the twentieth century. Yet Graham consistently avoided overt partisanship, preferring to frame his ministry in broadly moral and spiritual terms. His reluctance to fully embrace the political right left a vacuum for more aggressive leaders to fill in the late 1970s.12 Graham’s model demonstrated the potential reach of evangelical Christianity but also underscored the limitations of a nonpartisan approach in an era of growing cultural conflict.

The Rise of New Leaders

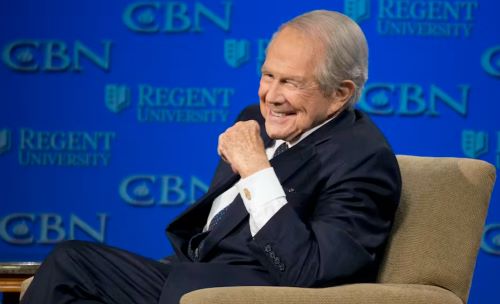

In Graham’s wake, a new generation of evangelical leaders adopted a more militant stance. Jerry Falwell, a Baptist pastor from Lynchburg, Virginia, emerged as the most prominent spokesman. His Liberty Baptist College (later Liberty University) and nationally syndicated “Old-Time Gospel Hour” provided both a base and a megaphone for mobilization. Pat Robertson built a similar empire through the Christian Broadcasting Network, while intellectual figures like Francis Schaeffer articulated a theological justification for political engagement, warning that secular humanism threatened to destroy the moral foundations of Western civilization.13

These figures fused theology with politics, framing liberalism not merely as a competing policy vision but as a spiritual enemy. Their rhetoric of moral emergency resonated with millions of evangelicals who felt alienated by the cultural revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s.

Flashpoints of Evangelical Mobilization

Several issues catalyzed evangelical activism in this period, often more potent in combination than in isolation.

- Roe v. Wade (1973): The Supreme Court’s landmark decision legalizing abortion nationwide was initially met with mixed evangelical responses. The Southern Baptist Convention even issued statements in the 1970s supporting limited access to abortion. Yet by the latter part of the decade, abortion was reframed as a central moral crisis, aided by Catholic–evangelical collaboration.14

- The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA): Feminist activism, epitomized by the ERA campaign, drew evangelical backlash. Leaders such as Phyllis Schlafly mobilized conservative Christian women against the amendment, arguing it threatened traditional gender roles and family structures. Evangelical preachers echoed these themes from pulpits across the country.15

- Gay Rights: The push for local anti-discrimination ordinances in the 1970s provoked evangelical resistance. Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign in Miami (1977) captured national attention and provided a template for later religious-right organizing against LGBTQ rights.16

- School Prayer and Secularization: Following Supreme Court rulings in Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington v. Schempp (1963), evangelicals increasingly lamented the removal of prayer and Bible reading from public schools. Though these cases predated Roe, the 1970s saw renewed emphasis on “secular humanism” as the enemy of Christian culture.17

Together, these flashpoints fostered a sense of existential threat. Evangelical leaders portrayed the decade as a time of moral decline, in which Christians had to “take back America” from secular elites. The stage was set for the formation of the Moral Majority and the alliance with Reagan in 1980.

The Moral Majority and Reagan’s 1980 Victory

Overview

By the close of the 1970s, evangelical discontent with the cultural and political order had coalesced into an organized political movement. The most significant institutional expression of this awakening was the Moral Majority, founded in 1979 by Jerry Falwell. Under its banner, evangelicals entered national politics with a vigor and coordination that fundamentally altered the Republican Party and propelled Ronald Reagan to the presidency.

Formation of the Moral Majority

The Moral Majority emerged as a coalition of fundamentalists, conservative evangelicals, and traditionalist Catholics united around a shared agenda: opposition to abortion, feminism, gay rights, and secularism, alongside support for school prayer, strong national defense, and family values. Falwell declared that the Moral Majority sought to “reverse the moral decay” of American life, a message amplified through his church network, broadcasting platforms, and direct-mail campaigns.18

At its peak, the Moral Majority claimed millions of members and mobilized tens of thousands of churches across the country. While its numbers were sometimes inflated, its impact was undeniable: for the first time, evangelicals were organized into a mass political constituency that could rival labor unions and civil rights groups in influence.19

The Reagan Alliance

The Moral Majority found its ideal political partner in Ronald Reagan. Although Reagan himself was not particularly devout, his church attendance was sporadic, he skillfully used evangelical rhetoric to signal solidarity. In a famous address to evangelical leaders in Dallas in August 1980, Reagan told them: “I know you can’t endorse me, but I endorse you.”20 This declaration captured the new alignment: Reagan embraced the moral concerns of evangelicals, and in turn, they delivered him a decisive electoral base.

Jimmy Carter, by contrast, proved a disappointment to many evangelicals. Despite being the first openly “born-again” president, Carter refused to pursue school prayer amendments and hesitated to oppose abortion forcefully. Evangelical leaders increasingly accused him of betraying their values, and Carter’s support among white evangelicals collapsed by 1980.21 Reagan capitalized on this disenchantment, portraying himself as the true defender of Christian America.

Electoral Impact of 1980

Evangelical turnout in 1980 was unprecedented. An estimated two-thirds of white evangelicals voted for Reagan, helping him win in key battleground states such as Texas, Florida, and Ohio.22 The Republican Party platform, heavily influenced by the Moral Majority and allied groups, incorporated strong opposition to abortion, support for voluntary school prayer, and explicit commitments to “family values.”23

The 1980 election thus marked more than just Reagan’s personal triumph; it represented the institutionalization of the evangelical–Republican alliance. From this point forward, evangelicals were not merely a voting bloc but the cultural backbone of the GOP. The Moral Majority, though it would decline by the late 1980s, had demonstrated the power of evangelical mobilization, setting a precedent for future organizations like the Christian Coalition in the 1990s.

Institutionalization of the Evangelical–Republican Alliance

Overview

While the Moral Majority was the symbolic spearhead of evangelical political activism, the 1980s witnessed the deeper institutional embedding of evangelical priorities within the Republican Party. Through policy battles, organizational infrastructure, and media ecosystems, the evangelical–GOP alliance became more than an electoral marriage of convenience; it was a lasting cultural and political reorientation.

Policy Outcomes in the Reagan Years

The Reagan administration provided evangelicals with symbolic validation, even if it did not always deliver substantive legislative victories. Abortion was a central rallying point. Reagan endorsed the Hyde Amendment, which barred federal funding for abortion, and appointed outspoken pro-life figures to his administration. In 1981, his Justice Department issued briefs in support of restrictions on abortion, and Reagan himself published a book, Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation, articulating his opposition.24 Although Roe v. Wade was not overturned, evangelical leaders felt that for the first time a president publicly championed their moral cause.

Other policy battles included efforts to reintroduce voluntary school prayer through constitutional amendment. While these initiatives consistently failed in Congress, their prominence in Reagan’s agenda reassured evangelicals that their concerns had entered the national mainstream.25 The administration also sought to roll back regulations on Christian schools and protect their tax-exempt status in the wake of the Bob Jones controversy, though the Supreme Court ultimately sided against the university in 1983.26

Judicial appointments were perhaps the most consequential area of institutionalization. Reagan’s nomination of Antonin Scalia to the Supreme Court in 1986, and his elevation of William Rehnquist to Chief Justice, reflected a new emphasis on conservative jurisprudence that evangelicals hoped would one day reverse Roe and reshape constitutional interpretation.27

Think Tanks, PACs, and Media Networks

The 1980s also saw the proliferation of evangelical-aligned institutions that extended the reach of the movement beyond electoral cycles. Conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation and the Free Congress Foundation developed policy blueprints infused with evangelical moral concerns. Political action committees (PACs), including the National Conservative Political Action Committee (NCPAC), provided the financial muscle to back evangelical-friendly candidates at every level of government.28

Equally significant was the rise of evangelical media. Televangelism became a cultural juggernaut, with figures like Falwell, Robertson, and Jim Bakker reaching millions of viewers weekly. Christian radio stations multiplied, disseminating political as well as spiritual content. This infrastructure created an alternative public sphere where evangelical perspectives dominated unchallenged, reinforcing partisan identity and mobilizing grassroots activism.29

Critiques and Fractures

Yet not all evangelicals welcomed this politicization. Some leaders, including Billy Graham, cautioned that the church risked compromising its spiritual mission by aligning too closely with partisan politics. Others argued that the Moral Majority and its successors alienated moderate Christians and reduced the gospel to a platform plank. By the late 1980s, scandals involving televangelists such as Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart damaged the credibility of the movement, fueling public skepticism about the entanglement of faith and politics.30

Despite these fractures, the core achievement of the 1980s was clear: evangelicals were no longer outsiders to American politics but central actors within the Republican Party. Their influence extended beyond elections to shape the ideological trajectory of conservatism itself, ensuring that the GOP’s future would be inseparable from evangelical identity.

Long-Term Consequences and the Legacy of the 1980s

Overview

The institutionalization of the evangelical–Republican alliance in the Reagan era reshaped not only the politics of the 1980s but also the trajectory of American conservatism into the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The evangelical surge of the Reagan years created enduring patterns of party identity, electoral strategy, and cultural conflict that would outlast the Moral Majority itself.

Continuation and Transformation in the 1990s

Although the Moral Majority formally dissolved in 1989, evangelical political activism hardly faded. Instead, it reconstituted under new organizational forms. Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition, founded in 1989, quickly became the most powerful religious-right organization of the 1990s, boasting a membership of nearly two million and distributing voter guides to churches nationwide.31 Under the leadership of Ralph Reed, the Christian Coalition perfected grassroots mobilization strategies, ensuring evangelical dominance in Republican primaries.

Evangelicals played a central role in shaping opposition to the Clinton administration, particularly on issues of abortion, gay rights, and the role of government in healthcare. The 1994 Republican “Contract with America” drew heavily on evangelical themes of family, morality, and limited government, reflecting the extent to which religious conservatism had become indistinguishable from party orthodoxy.32

From George W. Bush to Donald Trump

The early 2000s confirmed the evangelical hold on Republican politics. George W. Bush, who openly spoke of his evangelical conversion experience, made “faith-based initiatives” a cornerstone of his administration. Evangelicals responded by giving Bush overwhelming support, especially in the 2004 election, where ballot measures opposing same-sex marriage helped drive turnout in key states.33

The rise of Donald Trump in 2016 presented a paradox. A thrice-married casino mogul with little personal piety, Trump seemed an unlikely evangelical champion. Yet white evangelicals supported him at rates surpassing even those for Reagan or Bush. Scholars argue that evangelicals redefined their political identity less around personal morality and more around cultural defense, viewing Trump as a “bulwark” against secular liberalism, immigration, and demographic change.34 The alliance between Trump and evangelicals underscored how deeply the partisan identity forged in the Reagan era had endured: evangelicals were no longer simply participants in the Republican Party, but its defining base.

Evangelical Identity and the Republican Party

By the twenty-first century, evangelicals constituted the GOP’s most reliable constituency, with upwards of 80 percent of white evangelical voters consistently supporting Republican presidential candidates.35 This shift marked the collapse of the old Republican establishment, once rooted in mainline Protestantism, business interests, and moderate conservatism. The GOP had become, in large measure, the political expression of evangelical cultural identity.

The long-term consequences have been profound. The evangelical takeover reshaped constitutional debates on abortion, same-sex marriage, and religious liberty; fueled the culture wars of the 1990s and 2000s; and contributed to the deep partisan polarization of contemporary America. What began as a reaction to desegregation battles and cultural upheavals in the 1960s and 1970s culminated in a Republican Party remade in the image of evangelical conservatism. The “Great Reversal” was thus not only a political realignment but a cultural transformation whose legacy continues to define American democracy.

Conclusion

The evangelical takeover of the Republican Party was not a sudden rupture but the culmination of decades of social, cultural, and political transformations. Rooted in the civil rights backlash and the defense of Christian institutions in the 1960s and 1970s, evangelical mobilization found organizational form in the Moral Majority and ideological validation in Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Though the Moral Majority itself faded, the institutional groundwork of the 1980s permanently aligned evangelicals with the Republican Party, ensuring their dominance in shaping party platforms, judicial nominations, and cultural discourse.

This alliance redefined American politics. Evangelicals, once wary of overt political entanglement, emerged as the most reliable and cohesive voting bloc in the GOP. Their concerns (abortion, school prayer, gender roles, and cultural authority) became synonymous with Republican identity. The party’s transformation was so thorough that by the twenty-first century, evangelical Christianity and Republican partisanship were often indistinguishable in both rhetoric and electoral outcomes.

The consequences for American democracy have been profound. Evangelical political power intensified the culture wars, contributed to hyper-partisan polarization, and shifted debates about the Constitution, morality, and public life. As scholars such as Frances FitzGerald and Robert P. Jones remind us, this merger of faith and politics has not only reshaped the Republican Party but also recast the nation’s understanding of itself.36 Whether seen as a moral revival or as a distortion of democratic pluralism, the evangelical ascendancy represents one of the most significant realignments in modern American history.

The Great Reversal, therefore, was not merely a partisan shift of Southern voters from Democrat to Republican. It was a transformation in the very grammar of American politics: where the language of evangelical Christianity became inseparable from the vocabulary of conservatism. The legacy of this fusion, cemented in the Reagan years and carried forward into the Trump era, continues to shape the contested landscape of American democracy in the twenty-first century.

Postscript: Donald Trump’s Personal “Great Reversal”

The irony of Donald Trump’s later position as the champion of white evangelical conservatism is that he himself underwent a striking partisan transformation, one that in some ways mirrored the broader realignment of the Republican Party decades earlier. Public records reveal that Trump was a registered Democrat from 2001 until 2009, during which time he donated to prominent Democrats, expressed support for abortion rights, and embraced positions more aligned with the liberal establishment of New York City than with the social conservatism of the Republican base.37 In a 1999 interview, he described himself as “very pro-choice,” a stance that would later seem almost unthinkable given his role as the president who appointed the justices who overturned Roe v. Wade.38

Trump’s abrupt pivot came in the aftermath of Barack Obama’s election in 2008. Just as the Republican Party’s Great Reversal in the mid-twentieth century was catalyzed by backlash against desegregation and civil rights, Trump’s personal reversal followed the election of the nation’s first Black president. His sudden embrace of conservative rhetoric (most notably through his championing of the “birther” conspiracy, which falsely questioned Obama’s citizenship) marked both a political and cultural realignment. This pivot positioned Trump as a voice for those who felt alienated by demographic change and liberal ascendency, echoing the grievances that had driven the earlier evangelical migration into the Republican fold.39

In this sense, Trump’s personal Great Reversal did not simply parallel the party’s earlier transformation; it reenacted it on an individual level. His shift was less about ideology than about identity and resentment, less about a considered philosophy than about seizing the language of grievance that had long fueled the evangelical–Republican alliance. It was this adaptation that allowed a man with little personal religiosity to become, in the eyes of white evangelicals, their most powerful political champion since Reagan.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Frances FitzGerald, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 507–12.

- Kevin M. Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 23–45.

- Daniel K. Williams, God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 115–42.

- Randall Balmer, Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts Faith and Threatens America (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 13–27.

- Quoted in Thomas Byrne Edsall and Mary D. Edsall, Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights, and Taxes on American Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 1992), 178.

- Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Knopf, 2012), 475.

- Dan T. Carter, The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 289–316.

- Matthew Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 215–48.

- Rick Perlstein, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 392–410.

- U.S. Supreme Court, Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983).

- Balmer, Thy Kingdom Come, 13–27; Williams, God’s Own Party, 115–42.

- Grant Wacker, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 278–301.

- Michael Lienesch, Redeeming America: Piety and Politics in the New Christian Right (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 65–89.

- Daniel K. Williams, Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 197–223.

- Donald T. Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman’s Crusade (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 225–56.

- Lillian Faderman, The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 241–56.

- Steven P. Miller, The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 72–94.

- Jerry Falwell, Listen, America! (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980), 15–27.

- William Martin, With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America (New York: Broadway Books, 1996), 191–214.

- Quoted in Frances FitzGerald, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 528.

- Steven P. Miller, Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 212–18.

- Robert Wuthnow, The Restructuring of American Religion: Society and Faith Since World War II (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 177.

- Republican Party Platform, 1980, available in Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, eds., The American Presidency Project (Santa Barbara, CA: University of California).

- Ronald Reagan, Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1984).

- Steven P. Miller, The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 98–112.

- Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983).

- Mark Tushnet, A Court Divided: The Rehnquist Court and the Future of Constitutional Law (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 31–56.

- Sidney Blumenthal, The Rise of the Counter-Establishment: From Conservative Ideology to Political Power (New York: Times Books, 1986), 204–19.

- Martin, With God on Our Side, 235–52.

- Wacker, America’s Pastor, 315–22.

- Clyde Wilcox and Carin Robinson, Onward Christian Soldiers? The Religious Right in American Politics, 4th ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), 89–113.

- Dan T. Carter, From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 251–67.

- David Domke and Kevin Coe, The God Strategy: How Religion Became a Political Weapon in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 156–74.

- Robert P. Jones, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 219–34.

- Pew Research Center, “How the Faithful Voted: A Preliminary 2016 Analysis,” Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, November 9, 2016.

- FitzGerald, The Evangelicals, 623–34; Jones, White Too Long, 247–60.

- Jessica Chasmar, “Trump Changed Parties at Least Five Times,” Washington Times, June 16, 2015.

- “Donald Trump: ‘I’m Very Pro-Choice,’” Meet the Press, NBC News, October 24, 1999.

- Jonathan Rieder, Gospel of Freedom: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and the Struggle That Changed a Nation (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 291–94; see also Randall Balmer, “The Real Origins of the Religious Right,” Politico Magazine, May 27, 2014.

Bibliography

- Balmer, Randall. Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts Faith and Threatens America. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

- Balmer, Randall. “The Real Origins of the Religious Right.” Politico Magazine, May 27, 2014.

- Blumenthal, Sidney. The Rise of the Counter-Establishment: From Conservative Ideology to Political Power. New York: Times Books, 1986.

- Caro, Robert A. The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power. New York: Knopf, 2012.

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995.

- ———. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

- Chasmar, Jessica. “Trump Changed Parties at Least Five Times.” Washington Times, June 16, 2015.

- Critchlow, Donald T. Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman’s Crusade. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Domke, David, and Kevin Coe. The God Strategy: How Religion Became a Political Weapon in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Edsall, Thomas Byrne, and Mary D. Edsall. Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights, and Taxes on American Politics. New York: W.W. Norton, 1992.

- Faderman, Lillian. The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

- Falwell, Jerry. Listen, America!. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980.

- FitzGerald, Frances. The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

- Jones, Robert P. White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020.

- Kruse, Kevin M. One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

- Lassiter, Matthew. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Lienesch, Michael. Redeeming America: Piety and Politics in the New Christian Right. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Martin, William. With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America. New York: Broadway Books, 1996.

- Miller, Steven P. Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

- ———. The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- NBC News. “Donald Trump: ‘I’m Very Pro-Choice.’” Meet the Press, October 24, 1999.

- Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- Pew Research Center. “How the Faithful Voted: A Preliminary 2016 Analysis.” Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. November 9, 2016.

- Reagan, Ronald. Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1984.

- Rieder, Jonathan. Gospel of Freedom: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and the Struggle That Changed a Nation. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

- Tushnet, Mark. A Court Divided: The Rehnquist Court and the Future of Constitutional Law. New York: W.W. Norton, 2005.

- U.S. Supreme Court. Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983).

- Wilcox, Clyde, and Carin Robinson. Onward Christian Soldiers? The Religious Right in American Politics. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996.

- Williams, Daniel K. Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- ———. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Wuthnow, Robert. The Restructuring of American Religion: Society and Faith Since World War II. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Wacker, Grant. America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.