The working class of ancient Rome remains, in many respects, a hidden majority. Their lives rarely occupy the center of our surviving literary sources, which were written by and for elites.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

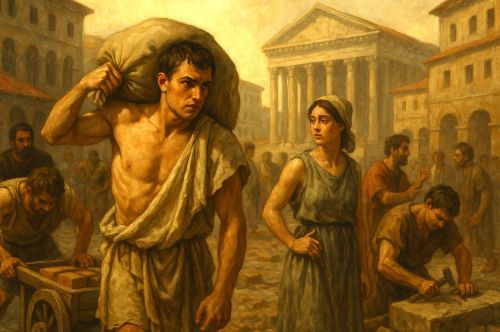

To speak of a “working class” in ancient Rome is, at the outset, to navigate a tension between modern categories and ancient realities. Historians have long debated whether the language of “class,” with its Marxian echoes of labor and capital, can be applied to societies that lacked both modern industry and a self-conscious proletariat. Yet the social and economic fabric of Rome was undeniably composed of men and women who lived by their hands and labor: tenant farmers in the countryside, artisans and tradesmen in the city, dockworkers on the Tiber, freedmen running shops, and slaves whose toil was both coerced and indispensable. These individuals, diverse in status and circumstance, collectively formed the indispensable backbone of Rome’s economy and its imperial grandeur.

The historiography of Roman labor has shifted dramatically in the past half-century. Moses Finley famously argued that Rome’s economy was “primitive,” embedded in social relations rather than market mechanisms, thereby limiting the agency of free wage labor in shaping broader structures of production.1 Keith Hopkins, by contrast, emphasized the social and economic transformations wrought by conquest, enslavement, and redistribution, situating Rome’s working population in a more dynamic system of economic change.2 More recent scholarship has explored the complexities of freedmen’s social roles, the realities of urban guilds, and the precariousness of daily subsistence in both the city and countryside.3 What emerges from this body of work is not a unified “class” in the modern sense, but rather a spectrum of laboring groups whose existence was defined by economic vulnerability, political marginality, and cultural ambivalence.

This essay examines the working class in ancient Rome through multiple lenses: their occupations and livelihoods, their economic conditions, their cultural and social identities, and their role in politics and public life. By situating these laboring populations within both the material structures of Roman society and the ideological frameworks imposed by elites, we can better understand how the Roman world functioned at its most fundamental level. Rome’s grandeur (its aqueducts, forums, baths, circuses, and armies) was not conjured ex nihilo by emperors and senators, but built and sustained by the millions whose lives rarely entered the pages of Livy or Tacitus. In recovering their story, we recover something essential about Rome itself.

Defining the Roman Working Class

The vocabulary of “class” in Rome is both fluid and elusive. Roman society was rigidly hierarchical in its legal and political distinctions, yet far less systematic in its social categories than modern class analysis would presume. The most familiar dichotomy is between patricii and plebeii, but by the late Republic and early Empire this ancient distinction had lost much of its practical significance. Instead, the term plebs, particularly the plebs urbana, was used to describe the mass of ordinary free citizens who lacked wealth, office, or noble ancestry.4 Among them existed profound variations: prosperous artisans, small shopkeepers, day laborers, and impoverished citizens reliant on public distributions.

Beyond the freeborn plebs, the Roman working population encompassed freedmen (liberti), whose ambiguous status placed them in a liminal space between slavery and citizenship. Freedmen often rose to prominence in commerce, industry, and even imperial administration, though they carried the indelible social stigma of servile origins.5 Slaves themselves, legally excluded from citizenship, formed the largest body of laborers in Rome. They worked in households, workshops, mines, farms, and docks, sustaining nearly every aspect of urban and rural life.6 Finally, in the countryside, coloni (tenant farmers) and smallholding peasants, often deeply indebted, labored under conditions that tethered them to elite landowners while leaving them vulnerable to economic fluctuation and natural disaster.

The absence of a unified identity among these groups has led many scholars to question the appropriateness of the term “working class” altogether. Henrik Mouritsen emphasizes that Roman freedmen, unlike a modern proletariat, had access to civic participation and entrepreneurial opportunities that blurred the line between dependency and autonomy.7 At the same time, Fergus Millar highlights the ways in which the urban plebs functioned collectively, particularly as a political crowd, capable of exerting real pressure on elites through assemblies, protests, and riots.8 Taken together, these observations suggest that Rome’s laboring groups, though fragmented, can be understood as a “working class” insofar as their existence was defined by labor, their freedom constrained by economic precarity, and their power circumscribed by elite domination.

Labor and Occupations

The Roman working population sustained itself and the empire through a diverse array of occupations, ranging from the agrarian labor of the countryside to the specialized trades and services of Rome and its provincial cities. Agriculture remained the backbone of the Roman economy. Smallholding peasants cultivated their plots, but many fell into debt or dependency upon larger estates. Tenant farmers (coloni) often leased land from elite landowners, bound by contracts that left them vulnerable to fluctuating harvests and exploitative rents.9 In addition, seasonal laborers were frequently employed during harvests, underscoring the precariousness of rural employment.

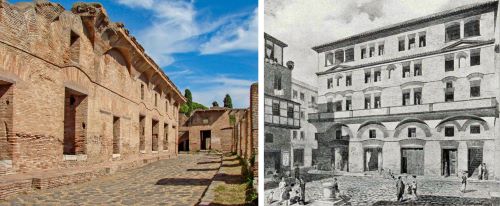

In urban contexts, occupations multiplied. Rome’s artisans included builders, potters, smiths, bakers, fullers, and weavers, whose workshops lined the insulae of the Subura and the port city of Ostia.10 Dockworkers along the Tiber and at Ostia played a particularly crucial role in the storage and distribution of imported grain, oil, and wine.11 Their labor, while largely invisible in elite literary sources, was indispensable to the functioning of the capital. Construction workers built aqueducts, temples, roads, and public monuments, projects that not only employed vast numbers of laborers but also symbolized the grandeur of imperial power.12

The collegia, associations of craftsmen and laborers, organized many of these trades. Though not equivalent to modern trade unions, these guilds provided a social and religious framework for workers, including burial clubs, communal banquets, and collective identity.13 While some scholars stress their limited political function, inscriptions reveal that collegia could serve as vehicles for patronage and, at times, as semi-political entities.14 Freedmen were especially prominent in these associations, reflecting their concentration in artisanal and commercial labor.

At the lowest end of the occupational spectrum were slaves, who were employed in virtually every field of labor. Domestic slaves staffed elite households, while others labored in workshops, on estates, or in Rome’s infrastructural projects.15 Slavery blurred the lines of “working class” status, since their lack of legal personhood placed them outside the category of citizen laborers, yet their toil constituted the foundation upon which the free labor economy was built.

Economic Conditions

For Rome’s working population, daily life was marked less by prosperity than by the constant negotiation of subsistence. Wage levels varied widely across occupations, but even skilled laborers often earned little more than what was necessary for daily survival. Surviving papyri and inscriptions suggest that wages for a manual worker could range from a few sesterces per day to slightly more for specialized artisans, though payments were frequently unstable or seasonal.16 Agricultural laborers were particularly vulnerable, dependent on the unpredictability of harvests, weather, and landlords’ demands.17

The urban poor depended heavily on the annona, the state-subsidized grain distribution. Beginning in the late Republic and expanded under Augustus, the grain dole provided monthly rations to citizens of Rome.18 While it did not eliminate poverty, the annona served as a safety net, forestalling famine and mitigating unrest among the plebs urbana. Its very existence underscores how precarious urban livelihoods were: without state intervention, many would have been unable to meet basic caloric needs.19 Elite critics, from Cicero to Juvenal, often disparaged the dole as fostering idleness, but such rhetoric masked the structural inequalities that forced workers into dependency.20

Housing costs further strained working-class budgets. The majority of Rome’s urban poor lived in insulae: multi-story tenement buildings that were often crowded, unsafe, and vulnerable to collapse or fire.21 Rent consumed a disproportionate share of wages, forcing many to share cramped quarters. The contrast with the domus of the wealthy highlighted the spatial inequality of the city. Even access to water was stratified: while aqueducts supplied the baths and fountains of the elite, poorer neighborhoods relied on public fountains and wells.22

Economic shocks could devastate the working class. Grain shortages, caused by war, piracy, or environmental disaster, drove up prices and rendered wages insufficient.23 Taxation in the provinces disproportionately burdened peasant farmers, who risked losing their land if unable to meet fiscal demands. In both city and countryside, the thin margin between survival and ruin meant that most of Rome’s workers lived lives of profound economic insecurity, constantly at the mercy of forces far beyond their control.

Social Life and Identity

The daily lives of Rome’s working population were shaped not only by labor and economic precarity but also by the cultural practices, communal spaces, and identities that gave meaning to existence. Housing conditions were the most visible marker of inequality. While elite families occupied spacious domus adorned with mosaics and atria, the vast majority of laborers lived in insulae, multi-story tenements that often crammed dozens of families into a single building.24 Fire and collapse were constant dangers, and overcrowding fostered both social intimacy and squalor.25 These material conditions created a distinct urban identity (dense, communal, and precarious) far removed from the villa culture celebrated in elite literature.

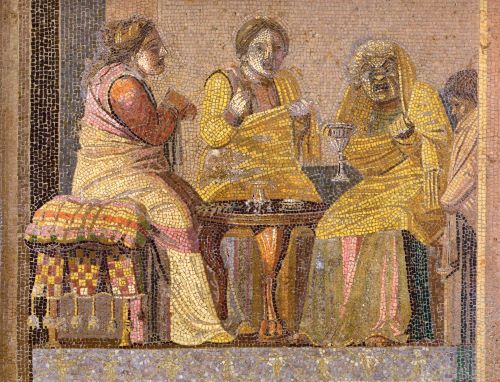

Leisure, though limited by financial constraints, offered the working class moments of respite and collective belonging. Public baths (thermae) were accessible even to the poor for a modest fee, serving as centers of hygiene, sociability, and relaxation.26 Likewise, taverns and wine shops provided inexpensive entertainment, though elite authors often associated them with vice.27 Above all, the circus and amphitheater offered a powerful venue for popular culture. The ludi circenses and gladiatorial games drew massive crowds, where the plebs urbana found both entertainment and a rare opportunity to express collective opinion.28

Religion was another critical dimension of working-class identity. Participation in household cults, neighborhood shrines (compita), and collegia reinforced social bonds.29 Collegia, in particular, served both professional and religious functions, binding members through worship of patron deities and collective banquets. Funerary inscriptions attest to the importance of these associations in providing burial benefits and ensuring remembrance, a crucial concern in a society where anonymity threatened the lower orders.30

The cultural divide between elite ideals and working-class realities was profound. Roman elites prized otium, the cultivated leisure of the landed aristocrat, while they denigrated labor as the mark of necessity and inferiority.31 Yet for the working class, labor was the unavoidable condition of existence, and identity was forged not in the villas of Cicero but in the streets, workshops, and insulae of Rome. This tension reveals not only social stratification but also the resilience of ordinary Romans, who carved out spaces of meaning and solidarity within the structures of inequality.

Political Engagement

Despite their economic precarity and social marginalization, Rome’s working populations were not politically inert. In the late Republic especially, the plebs urbana wielded real influence as a collective body, primarily through assemblies and the threat of mob action. The comitia tributa and concilium plebis provided citizens with the legal framework to vote on legislation and elect magistrates, even if elite patronage and manipulation often shaped outcomes.32 Politicians like the Gracchi brothers, Clodius Pulcher, and Julius Caesar mobilized the urban plebs by promising grain subsidies, land reform, and spectacles, illustrating both the agency of the working class and their instrumentalization by the elite.33

The phenomenon of the political crowd was central to this dynamic. Fergus Millar has emphasized that plebeian assemblies were not mere symbolic theater but genuine sites of deliberation and decision-making, however unruly.34 At the same time, these gatherings often spilled into riots, where the collective power of the plebs forced concessions from magistrates. Bread, circuses, and grain distributions were not simply elite tools of pacification but part of an ongoing negotiation between rulers and ruled.35

Under the Principate, however, the political agency of the working class diminished. Augustus and his successors retained the forms of popular assemblies but transferred substantive power to the Senate and, ultimately, the emperor himself.36 The urban plebs remained a visible presence, but their political role was increasingly expressed through acclamation at games, demonstrations of loyalty, and, at times, violent protest. The emperor’s duty to “care for the people” (cura annonae) reflected not just paternalism but recognition of the plebs’ potential for unrest.37

Patron-client relationships also structured political engagement. Working-class Romans sought protection and favors from elite patrons, who in turn mobilized clients as part of their political base.38 This reciprocity, while unequal, linked the fates of senators, equestrians, and plebs in a system that blurred the lines between social hierarchy and political participation. Freedmen, too, could enter into these networks, leveraging their economic activity and guild membership to build connections with more powerful figures.39

Though fragmented, the working class of Rome exerted an undeniable influence on the political culture of the city. Whether voting in assemblies, rioting in the Forum, or cheering in the Circus Maximus, they shaped the strategies of politicians and emperors alike, demonstrating that even in a society of stark inequality, power was never wholly monopolized by the elite.

Case Studies

The Building Trades in Rome and Ostia

The monumental architecture of Rome, from the Colosseum to the Baths of Caracalla, was made possible only by the vast numbers of laborers engaged in construction. Literary and archaeological evidence reveals the scale of these enterprises. Skilled artisans such as stonemasons, mosaicists, and carpenters worked alongside unskilled day laborers and slaves, often under the direction of imperial architects.40 Janet DeLaine’s study of the Baths of Caracalla demonstrates not only the massive coordination of resources but also the employment of thousands of workers over years of construction.41 The laboring poor, though largely anonymous in our sources, left their mark in graffiti, tomb inscriptions, and in the very fabric of the buildings they helped create.

Dockworkers at Ostia and Portus

Rome’s survival as a metropolis of over one million inhabitants depended on the grain shipments that arrived through its ports. Dockworkers (saccarii, navicularii) unloaded, stored, and transported goods from the harbors at Ostia and Portus to the city’s warehouses and markets.42 Epigraphic evidence shows that these workers often organized themselves into collegia, combining economic function with religious and social roles.43 Their labor was crucial to the functioning of the annona, linking the imperial administration with the lived experience of the plebs urbana. Despite their indispensability, they remained socially marginal, often residing in the poorer quarters of Ostia.44

Freedmen’s Associations

Freedmen offer one of the richest case studies for understanding the working population of Rome. Manumitted slaves often pursued occupations in trade, crafts, or administration, leveraging the entrepreneurial opportunities denied to most freeborn poor.45 Inscriptions from Pompeii, for instance, reveal freedmen serving as magistrates of collegia and patrons of local temples, reflecting their social mobility and community presence.46 Mouritsen has emphasized, however, that this mobility came with the stigma of servile origins, meaning that freedmen’s achievements often carried an ambivalent social status.47 Their associations provided mutual support, religious cohesion, and a means of collective visibility in a society otherwise structured to exclude them from the highest honors.

Together, these case studies highlight the diversity of Rome’s working population. Builders, dockworkers, and freedmen’s associations reveal not only the indispensable labor that sustained Rome but also the strategies through which ordinary people carved out spaces of community, identity, and limited influence within the structures of imperial society.

Conclusion

The working class of ancient Rome remains, in many respects, a hidden majority. Their lives rarely occupy the center of our surviving literary sources, which were written by and for elites, but they formed the indispensable base upon which the empire rested. Farmers, dockworkers, artisans, freedmen, and slaves produced the food, goods, infrastructure, and services that sustained the largest urban population of the ancient world. Their labor not only built the aqueducts, amphitheaters, and baths that symbolized Rome’s greatness but also ensured the daily functioning of an empire stretching from Britain to Syria.

The historiography of the Roman working class highlights both continuity and change. Finley’s characterization of a “primitive” economy stressed dependency and embeddedness, but subsequent scholarship has revealed a more nuanced picture, one where wage labor, freedmen’s enterprises, and collegia provided real, if limited, opportunities for agency.48 Economic insecurity and social marginality defined the conditions of laboring groups, yet they were far from passive: plebeian crowds influenced politics, dockworkers organized through collegia, and freedmen carved out new forms of identity.

What emerges from this study is not a coherent “class” in the modern Marxian sense, but rather a spectrum of laboring populations whose lives were united by necessity, vulnerability, and exclusion from elite ideals of otium.49 To speak of the Roman working class is, therefore, to acknowledge both the diversity of labor and the shared structural position of those whose existence was defined by work. Their story complicates the triumphalist narrative of Rome as an empire of emperors and senators, reminding us that its endurance rested on the shoulders of those least likely to be remembered.

Recovering the lives of Rome’s workers is more than an antiquarian exercise. It illuminates the dynamics of inequality in the ancient world, parallels with later societies, and the fragility of cultures that marginalize those who sustain them. As Keith Hopkins observed, Rome’s grandeur was inseparable from the exploitation and mobilization of its lower orders.50 By bringing the working class back into focus, we not only recover Rome’s forgotten majority but also confront the perennial question of how societies value, and devalue, the labor upon which they depend.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Moses I. Finley, The Ancient Economy, updated ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 22–25.

- Keith Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 98–120.

- Henrik Mouritsen, The Freedman in the Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 3–15.

- Peter Garnsey and Richard Saller, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 17–20.

- Henrik Mouritsen, The Freedman in the Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 41–68.

- Keith Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 100–103.

- Mouritsen, Freedman in the Roman World, 89–95.

- Fergus Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998), 18–22.

- Paul Erdkamp, The Grain Market in the Roman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 32–37.

- Lionel Casson, Everyday Life in Ancient Rome, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 66–75.

- Steven J. R. Ellis, The Roman Retail Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 52–55.

- Janet DeLaine, The Baths of Caracalla: A Study in the Design, Construction, and Economics of Large-Scale Building Projects in Imperial Rome (Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1997), 113–118.

- J. S. Kloppenborg and Richard S. Ascough, Greco-Roman Associations: Texts, Translations, and Commentary, vol. 1 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1988), 89–93.

- John Patterson, Landscape and Cities: Rural Settlement and Civic Transformation in Early Imperial Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 145–150.

- Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves, 121–124.

- Walter Scheidel, “Real Wages in Early Economies: Evidence for Living Standards from 1800 BCE to 1300 CE,” Journal of The Economic and Social History of The Orient 53:3 (2010): 452-462.

- Garnsey and Saller, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture, 38–42.

- Erdkamp, The Grain Market in the Roman Empire, 201–206.

- Peter Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 231–234.

- Juvenal, Satires 10.77–81; Cicero, Pro Sestio 103.

- J. E. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 132–135.

- Frontinus, De aquis urbis Romae 1.4; Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City, 140–143.

- Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply, 207–214.

- Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City, 127–133.

- Casson, Everyday Life in Ancient Rome, 42–47.

- Garrett G. Fagan, Bathing in Public in the Roman World (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 85–91.

- Juvenal, Satires 1.130–135; Martial, Epigrams 11.27.

- Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic, 249–252.

- Kloppenborg and Ascough, Greco-Roman Associations, 99–104.

- Mouritsen, The Freedman in the Roman World, 116–122.

- Garnsey and Saller, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture, 28–31.

- Cicero, De Legibus 3.19; Pro Sestio 106.

- Erich S. Gruen, The Last Generation of the Roman Republic (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 24–29.

- Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic, 32–36.

- Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World, 234–238.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 71–76.

- Suetonius, Divus Augustus 42; Cassius Dio, Roman History 55.10.

- Richard Saller, Personal Patronage Under the Early Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 15–19.

- Mouritsen, The Freedman in the Roman World, 173–178.

- Lionel Casson, Everyday Life in Ancient Rome, 88–92.

- DeLaine, The Baths of Caracalla, 119–123.

- Erdkamp, The Grain Market in the Roman Empire, 289–293.

- Kloppenborg and Ascough, Greco-Roman Associations, 201–206.

- Patterson, Landscape and Cities, 152–155.

- Mouritsen, The Freedman in the Roman World, 132–137.

- Alison E. Cooley, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (London: Routledge, 2013), 106–109.

- Mouritsen, Freedman in the Roman World, 140–144.

- Finley, The Ancient Economy, 22–27.

- Garnsey and Saller, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture, 28–33.

- Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves, 104–107.

Bibliography

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Casson, Lionel. Everyday Life in Ancient Rome. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- Cicero. De Legibus. Translated by Clinton W. Keyes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1928.

- ———. Pro Sestio. Translated by R. Gardner. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958.

- Cooley, Alison E. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, 2013.

- DeLaine, Janet. The Baths of Caracalla: A Study in the Design, Construction, and Economics of Large-Scale Building Projects in Imperial Rome. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1997.

- Ellis, Steven J. R. The Roman Retail Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Erdkamp, Paul. The Grain Market in the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Fagan, Garrett G. Bathing in Public in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Finley, Moses I. The Ancient Economy. Updated edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

- Frontinus. De aquis urbis Romae. Translated by C. E. Bennett. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1925.

- Garnsey, Peter. Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Garnsey, Peter, and Richard Saller. The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Gruen, Erich S. The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

- Hopkins, Keith. Conquerors and Slaves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Juvenal. Satires. Translated by Susanna Morton Braund. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Kloppenborg, J. S., and Richard S. Ascough. Greco-Roman Associations: Texts, Translations, and Commentary. Vol. 1. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1988.

- Martial. Epigrams. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. 2 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Millar, Fergus. The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- Mouritsen, Henrik. The Freedman in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Patterson, John. Landscape and Cities: Rural Settlement and Civic Transformation in Early Imperial Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Scheidel, Walter. “Real Wages in Early Economies: Evidence for Living Standards from 1800 BCE to 1300 CE.” Journal of The Economic and Social History of The Orient 53:3 (2010): 452-462.

- Saller, Richard. Personal Patronage Under the Early Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Stambaugh, J. E. The Ancient Roman City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988.

- Suetonius. Divus Augustus. Translated by J. C. Rolfe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Tacitus, Cornelius. The Annals of Imperial Rome. Translated by Michael Grant. London: Penguin, 1996.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.