The immobilization of peasants within the feudal order was neither accidental nor peripheral: it was fundamental to the system’s survival.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The figure of the medieval peasant has too often been cast as static, anonymous, and peripheral to the grand narratives of kings, knights, and clergy. Yet the daily lives of peasants, who composed the overwhelming majority of Europe’s population between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, were structured within a system designed less for their flourishing than for the benefit of an elite minority. The feudal order, while varied across regions and centuries, provided a framework of lordship and subordination that immobilized peasants within a rigid hierarchy. The mechanisms were multiple: legal restrictions on movement, customary obligations that tied families to the soil, economic burdens that drained surplus, and cultural or religious ideologies that sanctified inequality. Together these mechanisms forged a system in which peasants were bound to their stations, not by chance but by design.

This essay argues that feudalism should not be romanticized as a benign order of mutual obligations, as earlier historiography sometimes suggested, but rather understood as a structural means of channeling resources and labor upward to an aristocratic and ecclesiastical elite. The immobilization of peasants was not incidental but fundamental: the extraction of labor and produce required a population unable to exercise meaningful choice about leaving, resisting, or rising. In this sense, the feudal order can be analyzed as a form of what Marxist historians have called “extra-economic compulsion,” the imposition of obligations outside of market exchange that nonetheless ensured the steady transfer of surplus to lords and masters.1

The significance of such an inquiry lies not only in illuminating medieval social relations but also in challenging broader assumptions about the historical persistence of inequality. To understand how peasants were kept in their stations is to grasp how institutions reproduce class over generations, and how power operates not only through overt coercion but also through custom, belief, and the shaping of horizons of possibility. As Marc Bloch observed in his seminal Feudal Society, the system was “a web of rights and duties” that appeared reciprocal but functioned asymmetrically.2 More recent scholarship has extended this perspective, stressing both the variety of peasant experiences and the long-term effects of structural immobility on social development.3

What follows proceeds in several stages. It begins by examining the conceptual foundations of feudalism and the historiographical debates surrounding peasant immobility. It then analyzes the institutional and legal mechanisms that curtailed peasant freedom, followed by the economic dependencies that left households with little margin to maneuver. A further section considers the ideological and cultural frameworks that legitimated hierarchy and obedience. I also address resistance and negotiation, exploring both everyday evasions and large-scale revolts, before concluding with comparative reflections on regional variation and the eventual erosion of feudal constraints.

By tracing these interlocking mechanisms, this highlights the logic of feudal subordination as a system that maintained elite power at the expense of the many. It also raises broader questions about the persistence of inequality, the reproduction of social orders, and the ways in which human beings internalize or contest the roles assigned to them. Ultimately, the peasantry was not simply “there” in medieval society but actively constrained, shaped, and immobilized by structures that were at once legal, economic, and cultural. The story of their immobility is thus the story of feudalism itself.

Conceptual and Theoretical Foundations

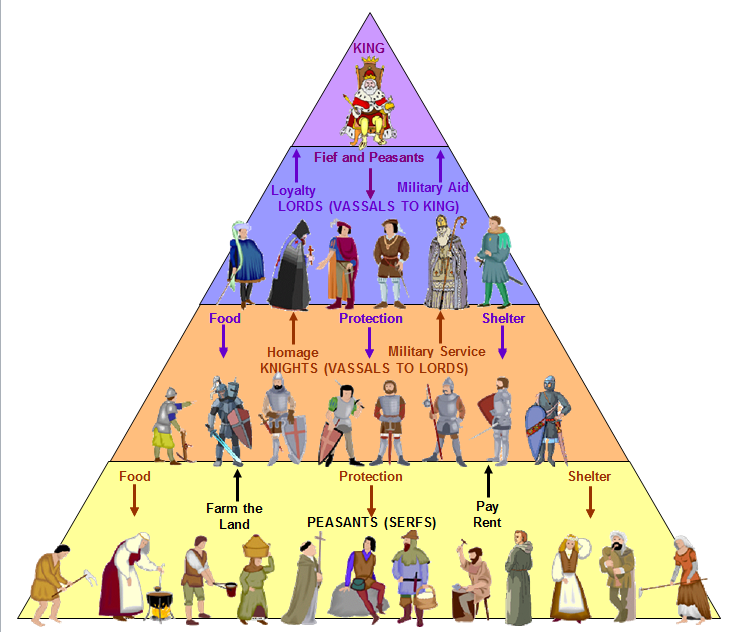

The term “feudalism” has long been both indispensable and controversial in the study of medieval Europe. Nineteenth-century historians popularized the idea of a singular “feudal system” that bound lords and vassals in personal ties of landholding and military service.4 Yet peasants were not vassals; they occupied the lower rungs of what scholars more precisely describe as manorialism, the organization of rural production, labor, and obligations under the authority of a lord.5 To conflate feudalism with manorialism risks obscuring the mechanisms through which peasants were immobilized. Nevertheless, the two were intertwined: the power of lords derived from feudal ties among elites, but their wealth was ultimately sustained by the labor and rents of those at the base of the pyramid.

The immobilization of peasants was not merely the product of personal domination but of institutions and legal norms that created “customary” obligations. As Paul Freedman has shown, many peasants believed themselves to be free even while subject to severe restrictions on their movements and livelihoods, a paradox created by the gradual naturalization of manorial duties.6 Such “customary law” was not written down in the same way as royal statutes but was enforced with equal or greater force at the local level. This localized legal culture exemplifies what Perry Anderson termed “extra-economic compulsion,” whereby the direct control of persons ensured the extraction of surplus beyond what free markets could achieve.7

The theoretical frameworks applied to the study of feudal society reveal competing emphases. Marxist historians such as Rodney Hilton and Georges Duby have interpreted the system as a “mode of production” structured by class conflict, with lords extracting rents and corvée labor from a subordinate class.8 By contrast, sociologists like Max Weber stressed the status dimension of feudal hierarchy, noting how the symbolic capital of noble lineage and honor codes buttressed economic exploitation.9 Both approaches converge on the insight that peasant immobility was not natural but constructed, a product of both material and ideological forces.

Historiography has increasingly highlighted that the image of the peasantry as a “nameless mass” is itself a distortion. Judith Bennett and other gender historians have demonstrated that peasant households varied significantly by wealth, gender roles, and access to community resources.10 Even within apparent immobility, there were differences in vulnerability and opportunity. Recent work in economic history, drawing on manorial accounts and tax registers, shows that intergenerational wealth persistence was strikingly high, particularly in places like late medieval Florence, where elite families maintained dominance across centuries while the majority of smallholders struggled to improve their lot.11 These findings underscore that while some peasants might maneuver within narrow margins, systemic barriers ensured the long-term reproduction of inequality.

The debate over “mobility” versus “immobility” is therefore more than semantic. Medieval society was not entirely closed: peasants could, in rare instances, move to towns, enter clerical life, or even purchase freedom. But as M. M. Postan observed, these instances were exceptions that proved the rule, and the overwhelming reality was continuity of status.12 For the vast majority, social horizons were bounded by obligations inherited at birth, sustained by custom, and reinforced by law. It is within this conceptual and theoretical framework that the immobilization of peasants must be understood.

Legal and Institutional Mechanisms of Immobilization

Overview

If peasants were to remain in their stations, the law had to do much of the work. Lords relied not only on military power but also on an intricate lattice of legal and institutional mechanisms to restrict mobility and reproduce dependence. These were not abstract regulations but living frameworks, enforced in local courts, embedded in contracts, and transmitted through custom.

Hereditary and Customary Tenure

At the heart of peasant immobility was tenure: peasants typically held land not as outright owners but as tenants bound to the manor. Tenure was hereditary, meaning children inherited both plots and obligations. Unlike freeholders, they could not sell their land without lordly consent, nor could they always subdivide it among heirs. Custom fixed families to the soil, ensuring a stable base of labor for the estate. As Susan Reynolds emphasizes, such “customary tenures” were defended by lords as ancient and immovable, even when evidence shows they were often innovations crafted to tighten control.13

Seigneurial Rights and Jurisdiction

Legal jurisdiction formed another pillar. Lords possessed judicial authority within their domains, often through manorial courts. These courts adjudicated disputes over debts, inheritance, trespass, and minor crimes. They also regulated peasants’ daily lives by enforcing obligations to use the lord’s mill or oven, collecting fines for defaulted labor, and controlling marriages.14

The court was both judge and creditor: the same authority that defined obligations also profited from their enforcement. This dual role reinforced lordly power while limiting avenues of redress.

Labor Obligations and Rents

In addition to tenure, peasants were required to provide labor service, or week-work. These obligations bound peasants to spend part of their week cultivating demesne land for the lord. Even when labor service was commuted into money rents during the later Middle Ages, the underlying principle remained: peasants were compelled to surrender a portion of their productive capacity. Rodney Hilton describes this as a fundamental form of “unfreedom,” whereby peasants could never work exclusively for their own households.15

Restrictions on Movement

Perhaps the clearest sign of immobilization was the restriction on geographical mobility. Serfs were typically forbidden to leave without permission. English law codified this as villeinage, a status that deprived peasants of legal recourse in royal courts and tied them directly to manorial jurisdiction.16

Fugitives could be pursued, seized, and forced to return. In continental Europe, similar mechanisms prevailed; in Catalonia, manumission fees created barriers to departure, while in parts of Eastern Europe, runaway peasants were hunted with the cooperation of neighboring lords.17 The immobility of labor was thus the linchpin of aristocratic wealth.

Manumission and Limited Freedom

Though manumission existed, it was exceptional. Lords could free a serf in exchange for money, service, or favor, but the practice was limited and selective. In many cases, manumission benefited the lord as much as the peasant, producing a cash payment in times of financial strain. As Chris Wickham notes, freedom was not a universal ideal in the medieval village but a negotiated privilege, one more opportunity for lordly profit.18

Statutory Reinforcement

Finally, royal statutes often reinforced seigneurial power. For example, England’s Statute of Labourers (1351) sought to cap wages and restrict worker mobility in the aftermath of the Black Death, effectively reasserting aristocratic control at a time when demographic crisis had emboldened peasants.19 Similar legislation in France, Castile, and parts of the Holy Roman Empire sought to freeze the rural workforce in place, demonstrating that the state and nobility could act in tandem to maintain immobility.

Taken together, these mechanisms reveal that the feudal order was not merely a loose social arrangement but a legal and institutional framework designed to bind peasants to land, lord, and duty. It was, in effect, a machinery of immobilization.

Economic Constraints and Material Dependence

Overview

Legal restrictions alone could not secure the subordination of the peasantry. The feudal order also relied on economic mechanisms that reinforced dependence, leaving peasants with little surplus or freedom of maneuver. Even when formal obligations weakened in some regions, structural constraints ensured that most households remained bound to subsistence and service.

Subsistence Pressure and Lack of Surplus

The medieval village was always close to the margins of survival. Climatic variability, crop failures, and recurrent famine left peasant households with few reserves. As Bruce Campbell notes in his study of England’s agricultural economy, subsistence farmers typically produced “barely enough to sustain themselves, let alone to resist seigneurial demands.”20

In such conditions, even modest dues could drive households into dependence. Scarcity, in other words, was not just a natural condition but a tool of control, since chronic insecurity discouraged resistance and compelled peasants to cling to the security of customary tenure.

Control of Land, Resources, and Commons

Lords held title to critical resources. Peasants had access to land, but the best fields often remained under direct demesne cultivation, and access to forests, rivers, and pastures was subject to lordly regulation. Rights of common grazing or firewood collection could be withdrawn or monetized.21 By controlling not only land but also mills, ovens, and presses, lords ensured that even basic necessities carried rents. Manorial monopolies funneled a steady stream of micro-payments upward, binding peasants to a cycle of dependence.

Market Constraints and Transaction Costs

Even when peasants entered markets, they did so under constraints. Lords frequently taxed transactions, levied tolls at bridges or markets, and imposed “banalities” that required peasants to use seigneurial facilities.22 Such practices limited the profitability of peasant trade. Moreover, high transaction costs discouraged long-distance trade, leaving most households confined to local economies where lords held dominant positions.

Debt, Credit, and Usury

Economic dependence was reinforced through credit relations. Peasants often borrowed grain or coin from lords, monasteries, or urban moneylenders to survive periods of scarcity. Default could result in loss of land or heavier obligations. As Jacques Le Goff has shown, the medieval economy functioned within a pervasive system of debt and pledges, with peasants caught in cycles that transferred assets to elites.23 Credit thus became not a pathway to upward mobility but a mechanism of social reproduction.

Demographic Shocks and Aristocratic Response

The Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century briefly disrupted this balance. With labor scarce, wages rose and some peasants negotiated better terms or abandoned servile tenures altogether.24

Yet elites responded with coercive legislation like England’s Statute of Labourers (1351) or France’s ordinances fixing wages, seeking to restore the pre-crisis hierarchy. The demographic catastrophe showed both the fragility and resilience of feudal constraints: while peasants gained bargaining power in the short term, the structural logic of immobilization reasserted itself within a generation.25

The economic dimension of immobility therefore rested not only on rents and dues but also on structural dependence: subsistence pressures, monopolies, debt, and state reinforcement. In such a system, even temporary opportunities for autonomy were circumscribed by institutions that ensured wealth and surplus flowed upward.

Ideological, Cultural, and Ritual Mechanisms

Overview

Coercion alone could not sustain the immobility of peasants. For the feudal order to endure, peasants had to internalize their subordination as part of the natural order of the world. Ideology, religion, and cultural practice thus served as essential complements to law and economics, embedding inequality into daily life and shaping the very imagination of what was possible.

Religious Legitimation and Moral Order

The Church provided the most powerful ideological reinforcement of feudal hierarchy. Medieval sermons and pastoral texts repeatedly emphasized the tripartite division of society: those who pray (clergy), those who fight (nobility), and those who work (peasants).26 This division was presented as divinely ordained, not socially constructed. By linking labor to sin and obedience to salvation, the Church endowed the peasant’s station with sacred necessity.27 To resist lord or priest was to resist God.

Custom, Tradition, and Social Norms

Custom was another form of soft power. As Paul Hyams observes, medieval law often blurred into custom, and custom itself was wielded as a weapon of control.28 Peasants might be told that their obligations stretched back to time immemorial, even when records show they were innovations. The invocation of “ancestral custom” gave coercive demands the appearance of timeless legitimacy. Social norms of deference (removing hats, bowing, using honorific titles) reinforced these hierarchies in everyday interaction.

Rituals and Symbolic Hierarchy

Symbolic practices dramatized inequality. Homage ceremonies, harvest festivals, and manorial courts were occasions where peasants performed subordination before their lord.29 In some villages, lords staged public displays, such as enforcing fines or compelling peasants to kneel in court, that reminded the community of their place. Ritualized hierarchy converted coercion into spectacle, reinforcing lordly prestige while normalizing submission.

Education, Literacy, and Discursive Control

Control of knowledge further reinforced immobility. Literacy rates among peasants remained extremely low, and texts (legal codes, theological treatises, manorial accounts) were monopolized by clerics and elites.30

Chronicles written by monks and clerics rarely gave peasants an independent voice, often portraying them as violent mobs or passive subjects.31 This discursive exclusion limited peasants’ ability to frame their own grievances within accepted narratives, confining their agency to oral complaint or rebellion.

Fragmentation and the Prevention of Solidarity

Finally, elites preserved immobility by discouraging peasant solidarity. Lords often co-opted wealthier peasants as intermediaries, granting them minor privileges in exchange for loyalty.32 Such stratification fractured villages, making unified resistance difficult. Inter-village rivalries and localism further prevented broader mobilization. In this way, social fragmentation became a tool of immobilization, ensuring that even when peasants resisted, they did so as isolated groups rather than a cohesive class.

Taken together, these ideological, cultural, and ritual mechanisms reveal that immobility was not only enforced by law and economy but also internalized by belief. Peasants learned to see their station as natural, customary, or sacred, and though cracks in this consensus periodically emerged, the system proved remarkably resilient across centuries.

Resistance, Negotiation, and the Limits of Immobilization

Overview

Despite the formidable legal, economic, and cultural apparatus designed to keep them bound, peasants were not merely passive recipients of lordly domination. They resisted, evaded, and occasionally revolted. Resistance ranged from the small acts of daily defiance to massive collective uprisings. These forms of contestation did not destroy the system, but they exposed its fragility and demonstrated that immobility was constantly contested.

Everyday Resistance and Evasion

James C. Scott’s influential framework of “everyday resistance” finds ample illustration in the medieval village.33 Peasants might feign illness to avoid labor service, work slowly on demesne fields, hide grain from tithe collectors, or use forests and meadows without permission. These acts rarely attracted chroniclers’ notice, but manorial court rolls reveal a steady trickle of minor offenses that reflect constant peasant pushback.34 Such “weapons of the weak” did not topple lordship, but they preserved small margins of autonomy.

Collective Revolt

At times, resentment exploded into rebellion. The Jacquerie in France (1358), the English Peasants’ Revolt (1381), and the German Peasants’ War (1524–25) all testify to the capacity of rural populations to organize on a large scale.35 These revolts often demanded reductions in dues, abolition of serfdom, or recognition of customary rights.

While brutally suppressed, they revealed the tension between immobilization and the aspiration to freedom. As Rodney Hilton argued, the English revolt in particular was not a spontaneous riot but a coordinated movement with political consciousness, challenging the legitimacy of villeinage.36

Legal Petitions and Negotiated Resistance

Resistance did not always take violent form. Many peasants appealed to royal courts, urban patrons, or even the Church to mediate disputes with their lords.37 Surviving petitions show peasants invoking “custom” to defend themselves, a rhetorical move that turned the language of lordship back upon itself. In some cases, legal challenges succeeded in winning reductions of fines or recognition of liberties. Negotiation, rather than confrontation, thus became a survival strategy.

Vertical Alliances and Exceptional Mobility

Though rare, instances of upward mobility did occur. Talented peasants could enter clerical careers, particularly in monasteries seeking recruits of modest origin.38 In other cases, wealthy peasants (kulaks in Eastern Europe, laboureurs in France) accumulated enough resources to acquire quasi-gentry status. Yet these cases remained exceptional, and as Guido Alfani has demonstrated, intergenerational wealth persistence overwhelmingly favored elites.39 For most, the barriers to sustained mobility were insurmountable.

Transition and Decline of Servile Constraints

By the later Middle Ages, demographic, economic, and political pressures eroded the foundations of servile immobility. The Black Death weakened labor supply, towns offered alternative livelihoods, and monarchies increasingly centralized authority at the expense of local lords.40

In England, commutation of labor dues into money rents became widespread, while in parts of Western Europe outright serfdom gradually disappeared. Still, as Robert Brenner has shown, this decline was not uniform: in Eastern Europe, the “second serfdom” of the sixteenth century intensified bondage rather than loosening it.41

Resistance therefore underscores both the limits and endurance of immobilization. Peasants found ways to subvert and challenge their station, yet the system proved adaptable, reasserting constraints whenever cracks appeared. The story of resistance is thus also the story of resilience, not only of peasants but of the structures that held them down.

Comparative and Regional Variation

Overview

The immobilization of peasants was not uniform across medieval Europe. Regional variations reveal how different political structures, demographic shifts, and economic pressures shaped the degree of constraint. Examining these contrasts highlights both the adaptability of feudalism and the universality of its goal: to preserve elite dominance by restricting peasant mobility.

Western Europe: Gradual Erosion of Servility

In Western Europe, particularly in England and parts of France, the late Middle Ages witnessed the gradual decline of classic serfdom. Commutation of labor dues into money payments expanded significantly after the Black Death, as lords found it easier to extract cash rents from a reduced labor force.42 The relative strength of urban economies also provided alternative livelihoods for peasants, undermining strict manorial control. By the fifteenth century, large areas of England had shifted to tenant farming with increasing numbers of freeholders, although many remained dependent on landlords for access to land.43

Eastern Europe: The “Second Serfdom”

In stark contrast, Eastern and Central Europe experienced the entrenchment of servitude well into the early modern era. From the fifteenth century onward, nobles in Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and later Russia imposed harsher restrictions on peasants, a phenomenon historians describe as the “second serfdom.”44

Rising demand for grain in Western markets gave Eastern landlords incentives to bind peasants more tightly, ensuring steady production for export. Runaway peasants were hunted down across borders, and lords acquired increasingly direct judicial powers over their tenants. As Sheilagh Ogilvie notes, this intensification of bondage reveals that feudal structures could regenerate when economic incentives aligned with elite interests.45

Case Studies: Florence and Central Europe

In regions like Tuscany, where archival records are abundant, patterns of continuity emerge. Florentine elites preserved their wealth across centuries, while peasants struggled to ascend socially despite periodic opportunities.46 Similarly, Markus Cerman’s studies of late medieval Central Europe show that land markets existed, but institutional constraints kept peasants from transforming tenure into mobility.47 Property transactions, far from liberating peasants, often reinforced existing hierarchies.

Beyond Europe: Feudal Analogues

Though “feudalism” remains a contested label outside Europe, comparisons are illuminating. In India, R. S. Sharma has argued that landholding elites extracted surplus from peasants in ways strikingly parallel to European manorialism, embedding immobility within both economic and ritual hierarchies.48

In the Ottoman Empire, the timar system bound peasants to land administered by cavalry officers, ensuring revenue flows to the state while restricting peasant mobility.49 In China, landlords wielded significant power over tenant farmers, though the imperial state often mediated, preventing the consolidation of hereditary serfdom on the European model.50 These analogues underscore that while forms of peasant immobility differed, the underlying principle, restricting rural producers for elite benefit, was not unique to Europe.

Lessons from Variation

The comparative record demonstrates that peasant immobility was neither inevitable nor uniform. Where towns and markets flourished, peasants carved out limited mobility; where elites retained military or judicial dominance, constraints deepened. This regional diversity highlights the structural flexibility of feudalism: its essence lay not in identical institutions, but in the reproduction of dependency across varied contexts.

Synthesis: How the Elite Benefited and the Structural Logic

Overview

The cumulative evidence demonstrates that feudalism was not simply a patchwork of local customs but a coherent structural logic. Its purpose, whether consciously articulated or not, was the reproduction of elite power through the immobilization of the peasantry. The system’s genius lay in its ability to integrate legal, economic, cultural, and ideological mechanisms into a web that made resistance costly and mobility nearly impossible.

Extraction of Surplus

At its core, the feudal order was an extraction machine. Labor services, cash rents, banal monopolies, and judicial fines all funneled resources upward. As Marc Bloch observed, lords “did not live on their own lands, but on the peasants’ lands”; their wealth derived from siphoning off surplus that peasants produced under duress.51 This structure of extraction enabled aristocrats to sustain military retinues, finance crusades, and build monumental estates, all without engaging in productive labor themselves.

The Balance of Coercion and Consent

The durability of the system depended on more than coercion. Force was certainly present, but equally important was the crafting of legitimacy. By presenting obligations as ancient custom or divine will, elites reduced the costs of enforcement and encouraged peasants to accept their place as natural.52 The interplay of coercion and consent thus gave feudalism its longevity. Where coercion dominated without legitimacy, as during moments of excessive taxation or war, revolt was more likely to erupt.

Social Reproduction Across Generations

The structural effect of immobility was the reproduction of inequality across generations. Children inherited their parents’ obligations and had few avenues for advancement. Wealth persisted overwhelmingly among elites, while peasants were trapped in cycles of scarcity, debt, and subordination.53 Even when moments of crisis (such as the Black Death) temporarily disrupted this balance, elites quickly recalibrated institutions to restore immobility. The system therefore proved not static but adaptive, constantly reinventing itself to maintain the downward flow of resources.

Transition and Adaptability

The eventual erosion of servile structures in Western Europe should not obscure their resilience. Feudalism adapted to demographic collapse by converting dues into money rents, to urban growth by monetizing resources, and to state centralization by aligning seigneurial rights with royal law.54

In Eastern Europe, elites responded to similar pressures by reinforcing bondage rather than abandoning it. The adaptability of the system underscores that its defining logic was not a fixed set of institutions but a persistent aim: to bind peasants in ways that preserved elite privilege.

Taken together, these dynamics reveal that peasant immobility was neither incidental nor peripheral, but central to the feudal project. It was the condition of possibility for aristocratic life, enabling elites to live by consuming the labor of others. Feudalism’s legacy, then, is not merely a medieval curiosity but a reminder of how inequality reproduces itself through a combination of force, ideology, and structural constraint.

Conclusion

The immobilization of peasants within the feudal order was neither accidental nor peripheral: it was fundamental to the system’s survival. By binding the majority of the population to the soil through a combination of legal obligation, economic dependency, cultural ritual, and religious justification, elites created a durable structure that secured their wealth and power at the expense of the many.

This has shown how the mechanisms of immobility operated on multiple levels. Legally, manorial courts, customary tenure, and statutes such as the English Statute of Labourers confined peasants to their obligations. Economically, lords controlled land, monopolized resources, and ensnared peasants in debt. Culturally and ideologically, the Church sanctified hierarchy, and ritual practices dramatized inequality. Even when peasants resisted through everyday evasion, petitions, or open revolt, the system adapted, reasserting its structural logic. The comparative perspective further demonstrates that while Western Europe gradually loosened servile ties, Eastern Europe tightened them, revealing the adaptability of feudalism in different contexts.

The elite few benefited immensely. The extraction of surplus underwrote aristocratic lifestyles, financed states and crusades, and perpetuated dynastic wealth across generations. The immobility of the peasantry, in turn, ensured that inequality was not a temporary imbalance but a long-term social fact. As recent scholarship has shown, wealth persistence across centuries was extraordinarily high, leaving most peasants with little prospect of mobility.55

Yet the endurance of immobility should not obscure its contested nature. Resistance was constant (sometimes quiet, sometimes explosive) and moments of crisis such as the Black Death reveal how fragile the system could become when demographic or economic shifts empowered peasants.56 Ultimately, feudalism’s legacy is not only the story of medieval lords and peasants but also a broader lesson in how social orders reproduce inequality: by embedding it in law, custom, belief, and daily life.

The study of medieval peasant immobility thus offers more than historical insight; it provides a lens for examining inequality in all eras. Whether in serfdom, slavery, or modern forms of labor dependency, the strategies of immobilization (restricting mobility, controlling resources, legitimizing hierarchy) remain strikingly familiar. The medieval village, in this sense, was not an anachronism but a prototype, reminding us that the persistence of inequality depends not only on force but on the construction of worlds in which subordination appears natural.57

Appendix

Footnotes

- Rodney Hilton, The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975), 12–15.

- Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, trans. L. A. Manyon (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1939), 59.

- Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 223–30.

- Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 1–12.

- Bloch, Feudal Society, 228–32.

- Paul Freedman, The Origins of Peasant Servitude in Medieval Catalonia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 45–47.

- Perry Anderson, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism (London: Verso, 1974), 149–53.

- Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381 (London: Routledge, 1973), 5–7; Georges Duby, Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West, trans. Cynthia Postan (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), 31–35.

- Max Weber, Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, ed. Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 1057–60.

- Judith M. Bennett, Women in the Medieval English Countryside: Gender and Household in Brigstock before the Plague (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 22–29.

- Guido Alfani and Matteo Di Tullio, The Lion’s Share: Inequality and the Rise of the Fiscal State in Preindustrial Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 119–24.

- M. M. Postan, The Medieval Economy and Society: An Economic History of Britain in the Middle Ages (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972), 85–88.

- Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals, 198–202.

- Zvi Razi, Life, Marriage and Death in a Medieval Parish: Economy, Society and Demography in Halesowen, 1270–1400 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 67–70.

- Hilton, The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages, 34–38.

- Paul Hyams, Kings, Lords and Peasants in Medieval England: The Common Law of Villeinage in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980), 112–16.

- Freedman, The Origins of Peasant Servitude in Medieval Catalonia, 96–101.

- Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages, 271–75.

- Anthony Musson, Medieval Law in Context: The Growth of Legal Consciousness from Magna Carta to the Peasants’ Revolt (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 139–43.

- Bruce M. S. Campbell, The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 72–75.

- Richard C. Hoffmann, Land, Liberties, and Lordship in a Late Medieval Countryside: Agrarian Structures and Change in the Duchy of Wrocław (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989), 101–4.

- Duby, Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West, 85–90.

- Jacques Le Goff, Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages, trans. Patricia Ranum (New York: Zone Books, 1986), 29–35.

- David Herlihy, The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, ed. Samuel K. Cohn (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 43–46.

- Musson, Medieval Law in Context, 144–47.

- Georges Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 15–18.

- Jacques Le Goff, Medieval Civilization 400–1500, trans. Julia Barrow (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988), 137–42.

- Paul R. Hyams, Rancor and Reconciliation in Medieval England (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), 59–64.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 188–92.

- Malcolm B. Parkes, Their Hands Before Our Eyes: A Closer Look at Scribes (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), 54–57.

- Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England (London: Hambledon and London, 2004), 92–95.

- Rodney Hilton, Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism (London: Verso, 1985), 211–15.

- James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), xv–xviii.

- Razi, Life, Marriage and Death in a Medieval Parish, 142–46.

- Peter Blickle, The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War from a New Perspective (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), 33–37.

- Hilton, Bond Men Made Free, 109–15.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, Of Good and Ill Repute: Gender and Social Control in Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 74–78.

- Lester K. Little, Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978), 92–95.

- Guido Alfani, “Economic Inequality in Preindustrial Times: Europe and Beyond.” Journal of Economic Literature 59:1 (2021), 3-44.

- Chris Wickham, Medieval Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 289–94.

- Robert Brenner, Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 32–36.

- R. H. Hilton, The Decline of Serfdom in Medieval England (London: Macmillan, 1969), 43–47.

- Zvi Razi and Richard Smith, Medieval Society and the Manor Court (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 198–202.

- Evsey Domar, “The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis,” Journal of Economic History 30, no. 1 (1970): 18–32.

- Sheilagh Ogilvie, Institutions and European Trade: Merchant Guilds, 1000–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 212–16.

- Alfani, Economic Inequality in Preindustrial Societies, 137–40.

- Markus Cerman, “Social Structure and Land Markets in Late Medieval Central and East-Central Europe,” Continuity and Change 24, no. 1 (2008): 55–86.

- R. S. Sharma, Indian Feudalism, c. 300–1200 (Calcutta: Macmillan, 1965), 71–75.

- Halil İnalcık, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973), 109–13.

- Philip C. C. Huang, The Peasant Family and Rural Development in the Yangzi Delta, 1350–1988 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), 32–37.

- Bloch, Feudal Society, 180–83.

- Duby, The Three Orders, 41–45.

- Alfani and Di Tullio, The Lion’s Share, 201–5.

- Brenner, Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe, 37–41.

- Alfani, Economic Inequality in Preindustrial Societies, 153–57.

- Herlihy, The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, 57–62.

- Anderson, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, 151–55.

Bibliography

- Alfani, Guido. “Economic Inequality in Preindustrial Times: Europe and Beyond.” Journal of Economic Literature 59:1 (2021), 3-44.

- Alfani, Guido, and Matteo Di Tullio. The Lion’s Share: Inequality and the Rise of the Fiscal State in Preindustrial Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Anderson, Perry. Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. London: Verso, 1974.

- Bennett, Judith M. Women in the Medieval English Countryside: Gender and Household in Brigstock before the Plague. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Blickle, Peter. The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War from a New Perspective. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975.

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society. Translated by L. A. Manyon. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1939.

- Brenner, Robert. Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Campbell, Bruce M. S. The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Cerman, Markus. “Social Structure and Land Markets in Late Medieval Central and East-Central Europe.” Continuity and Change 24, no. 1 (2008): 55–86.

- Domar, Evsey. “The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis.” Journal of Economic History 30, no. 1 (1970): 18–32.

- Duby, Georges. Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West. Translated by Cynthia Postan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968.

- Duby, Georges. The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- Freedman, Paul. The Origins of Peasant Servitude in Medieval Catalonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Given-Wilson, Chris. Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. Of Good and Ill Repute: Gender and Social Control in Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Herlihy, David. The Black Death and the Transformation of the West. Edited by Samuel K. Cohn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Hilton, Rodney. Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381. London: Routledge, 1973.

- Hilton, Rodney. Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism. London: Verso, 1985.

- Hilton, Rodney. The Decline of Serfdom in Medieval England. London: Macmillan, 1969.

- Hilton, Rodney. The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Hoffmann, Richard C. Land, Liberties, and Lordship in a Late Medieval Countryside: Agrarian Structures and Change in the Duchy of Wrocław. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

- Huang, Philip C. C. The Peasant Family and Rural Development in the Yangzi Delta, 1350–1988. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

- Hyams, Paul. Kings, Lords and Peasants in Medieval England: The Common Law of Villeinage in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

- Hyams, Paul R. Rancor and Reconciliation in Medieval England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003.

- İnalcık, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973.

- Le Goff, Jacques. Medieval Civilization 400–1500. Translated by Julia Barrow. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

- Le Goff, Jacques. Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages. Translated by Patricia Ranum. New York: Zone Books, 1986.

- Little, Lester K. Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

- Musson, Anthony. Medieval Law in Context: The Growth of Legal Consciousness from Magna Carta to the Peasants’ Revolt. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001.

- Ogilvie, Sheilagh. Institutions and European Trade: Merchant Guilds, 1000–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Parkes, Malcolm B. Their Hands Before Our Eyes: A Closer Look at Scribes. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008.

- Postan, M. M. The Medieval Economy and Society: An Economic History of Britain in the Middle Ages. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972.

- Razi, Zvi. Life, Marriage and Death in a Medieval Parish: Economy, Society and Demography in Halesowen, 1270–1400. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Razi, Zvi, and Richard Smith. Medieval Society and the Manor Court. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Reynolds, Susan. Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Scott, James C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

- Sharma, R. S. Indian Feudalism, c. 300–1200. Calcutta: Macmillan, 1965.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Wickham, Chris. Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Wickham, Chris. Medieval Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.