The citizen’s wary gaze, formed in the crucible of revolution, slavery, and urban unrest, remains fixed upon the figure of authority.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

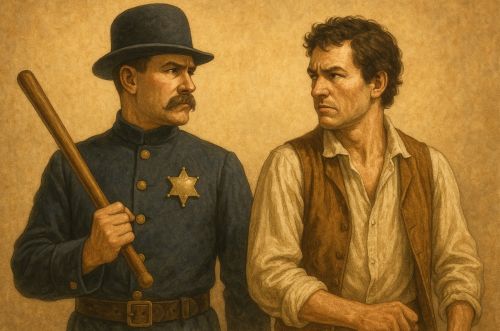

The first half of the nineteenth century was a formative period for law enforcement in the United States, a nation still experimenting with the balance between liberty and order, wary of power yet increasingly dependent on it. Between 1800 and 1850, Americans inhabited a political landscape haunted by the memory of royal troops in colonial streets and general warrants that had violated their homes. The Revolution had been, in part, a revolt against armed authority unmoored from consent. In the new republic that followed, citizens remained deeply suspicious of any force that might resemble a “standing army” in civilian life. Law enforcement was thus born into contradiction: indispensable for maintaining civic peace yet constantly scrutinized for its potential to threaten the very freedoms it was meant to secure.

In the early republic, there was no national police and scarcely any professional police at all. Order was maintained through sheriffs, constables, watchmen, and militias, figures whose powers were diffuse, local, and largely uncoordinated. These officers were accountable not to a centralized state but to county courts, town councils, or community elections. Yet that same decentralization, meant to protect liberty, produced a system ripe for abuse. Fee-based constables could extort rather than serve; watchmen might arrest with little oversight; and citizens, empowered through the ancient notion of posse comitatus, could be compelled into violence by local elites. Law enforcement was personal, improvised, and unpredictable. For many Americans, especially those in the new urban centers of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, this uneven patchwork blurred the line between protection and oppression.

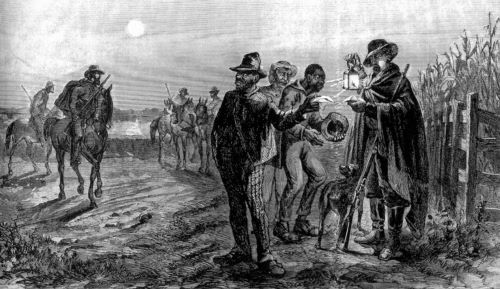

At the same time, beneath the republican rhetoric of liberty and law ran the darker architecture of slavery, a system that made racial subjugation a central feature of American policing. In the slaveholding South, law enforcement was inseparable from the maintenance of bondage. The slave patrols that swept through plantation districts were not a peripheral or accidental phenomenon; they were institutionalized forces of surveillance and terror, empowered by statute to whip, detain, and kill. These patrols represented the most naked form of state-sanctioned violence in early America. They also embodied the structural contradiction at the heart of the young republic: a nation that proclaimed freedom while enforcing bondage, that distrusted authority while constructing one of its most pervasive systems of racial control.1

By the 1830s and 1840s, as industrialization and urbanization accelerated, the old constabulary and watch systems faltered under the pressures of population growth, immigration, and disorder. Reformers began calling for permanent, salaried, and uniformed police forces modeled partly on London’s new Metropolitan Police of 1829. The resulting debates in Boston, New York, and other cities reflected not only concerns about crime but also fears of tyranny: whether the establishment of an organized police threatened to replicate the very abuses Americans had fought to escape. These anxieties reveal that, even as law enforcement modernized, its legitimacy remained fragile. Citizens viewed every badge as a potential emblem of despotism, every patrol as a possible encroachment upon republican freedom.

What follows explores this fraught landscape of authority and suspicion between 1800 and 1850, a period when the United States was simultaneously constructing its institutions of public order and contesting their moral and constitutional limits. It examines how citizens negotiated the paradox of freedom and control, how racial hierarchies shaped the application of law, and how the early forms of enforcement, ranging from sheriffs and watchmen to slave patrols and emerging city police, reflected the enduring tension between civic protection and coercive power. Through this lens, the story of American law enforcement before the Civil War becomes less a tale of progress toward professionalism than a drama of contested legitimacy, in which the promise of liberty was shadowed by the constant possibility of abuse.

The Policing Landscape, 1800–1830 — Local, Fragmented, and Racially Embedded

Overview

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, the United States possessed no national law enforcement apparatus and little conception of what “policing” in the modern sense would entail. Instead, it inherited from the English common law a decentralized mosaic of officers (sheriffs, constables, watchmen, and militias) whose authority was rooted in local statute, custom, and communal consent. This structure reflected both ideological conviction and institutional limitation. Americans had emerged from revolution convinced that concentrated power was the enemy of liberty; thus, coercive authority was to remain scattered and local, not centralized in any national or bureaucratic form.2 Yet this fragmentation, while intended as a safeguard against tyranny, created fertile ground for abuse. In the absence of uniform standards or consistent oversight, the administration of justice often depended upon personality, reputation, and whim.

Sheriffs, Constables, and the Watch

The sheriff was the most enduring of these offices, a direct descendant of the medieval English shire reeve. Elected or appointed at the county level, sheriffs combined administrative, judicial, and military duties: they served writs and warrants, collected taxes, conducted elections, managed county jails, and executed court orders.3 The sheriff’s wide jurisdiction made him both indispensable and dangerous. In rural America, where judicial institutions were sparse, sheriffs often wielded near-absolute local power, and abuses, particularly in debt collection and property seizures, were frequent subjects of complaint.4

Below the sheriff in the hierarchy stood the constables, typically appointed or elected at the township or municipal level. Their responsibilities were eclectic: arresting offenders, delivering subpoenas, maintaining the peace, and supervising the local watch.5 Many were paid by fees rather than salary, a system that rewarded activity over justice and encouraged corruption.6 Since few towns could afford to maintain full-time law officers, constables relied heavily on the unpaid or part-time night watch, ordinary citizens compelled by rotation or civic duty to patrol the streets after dark.7

The watch system, though inherited from colonial practice, had by the nineteenth century become widely derided as ineffective. Watchmen were poorly trained, poorly supervised, and often asleep or drunk on duty.8 They lacked the authority to investigate crimes or apprehend offenders beyond immediate disturbances. Their principal tasks were preventive and reactive: to cry the hour, watch for fires, and sound alarms for theft or violence.9 Newspapers of the 1820s regularly mocked the watch as an anachronism, a relic of small-town life unsuited to the growing complexity of urban America. Yet reform proposals to professionalize or expand policing were typically met with suspicion. Citizens feared that a salaried, uniformed force might evolve into a domestic army, a “standing police” whose loyalty lay with the state rather than the people.10

The Posse Comitatus and the Militia

Beyond these offices, the ancient common-law concept of posse comitatus empowered sheriffs to summon the able-bodied male population to assist in apprehending criminals or maintaining order.11 Theoretically a civic duty, this obligation reflected republican ideals of shared responsibility for law and order. In practice, however, it could transform citizens into instruments of repression. Sheriffs sometimes used posses to intimidate political opponents, break strikes, or enforce unpopular laws.12 In areas where social or racial tensions ran high, the line between lawful posse and mob blurred easily. The reliance on ad hoc citizen enforcement underscored both the weakness of formal institutions and the persistent distrust of permanent authority.

Militia forces also served quasi-policing functions. Governors or local magistrates might call out militia companies to suppress riots, enforce quarantines, or protect prisoners from lynch mobs.13 The deployment of armed citizens for internal security reflected the absence of a professional alternative but also mirrored the American anxiety about “regular” forces. The militia embodied the ideal of popular defense, armed yet civilian, coercive yet accountable through participation. But the militia’s very nature made restraint unreliable: the same emotional currents that animated civic zeal could ignite mob violence, particularly against marginalized groups.

Federal Marshals and the Fragile Reach of National Authority

The federal government’s contribution to law enforcement during this period was limited to the U.S. Marshals Service, established by the Judiciary Act of 1789.14 Marshals and their deputies executed federal warrants, served the courts, and enforced federal statutes, but their resources were minimal, and their reach seldom extended beyond major ports or territorial capitals. Their involvement in politically sensitive matters, such as the enforcement of fugitive slave laws, made them lightning rods for public resentment.15 For most Americans, “law enforcement” remained an affair of local custom rather than national power, reinforcing the belief that liberty was safest when government was near and known.

Citizens and the Anxiety of Power

Beneath these institutional forms lay a pervasive cultural fear: that those entrusted with law enforcement might themselves become lawless. Newspapers and legislative debates of the early republic are replete with warnings against “overbearing constables,” “tyrannical sheriffs,” and “mercenary watchmen.”16 Citizens remembered vividly the abuses of British enforcement under the writs of assistance and quartering acts; they saw in every uniform or badge the ghost of imperial domination.17 Consequently, the very design of early American policing aimed to prevent concentration of power, but in dispersing it, the system often sacrificed accountability.

This paradox defined the era’s law enforcement: a nation unwilling to empower authority yet unable to function without it. The result was an improvisational and deeply human system, prone to favoritism, corruption, and violence, yet sustained by republican ideals of local control. Those ideals, however noble in conception, concealed profound exclusions. In the southern states, law enforcement took on a far more sinister role: the organized surveillance and coercion of enslaved Africans and their descendants. There, the republican fear of tyranny was replaced by the planter’s fear of insurrection, and the machinery of order became the machinery of racial terror. To understand the origins of American policing fully, one must turn to that shadowed institution: the slave patrol.

Slave Patrols and the Enforcement of Racial Order

Overview

While the North experimented with constables and watchmen under the banner of civic republicanism, the South institutionalized a far more coercive model of control: the slave patrol. These units, sanctioned by statute and sustained by racial fear, reveal the deepest paradox of early American law enforcement. In a republic that proclaimed liberty as its founding virtue, entire systems of policing were constructed to deny liberty to others. Between 1800 and 1850, the patrols formed not merely an auxiliary arm of plantation management but an organized arm of the state, one that fused racial hierarchy with legal authority.

The Origins and Structure of Slave Patrols

Slave patrols were not a spontaneous response to disorder but an entrenched institution, with roots reaching back to the colonial era. South Carolina codified the practice in 1704, authorizing local militias to inspect slave quarters, search for weapons, and punish enslaved people found away from plantations without passes.18

By the early nineteenth century, similar laws were established throughout the South, from Virginia and North Carolina to Georgia and Mississippi. These statutes empowered local justices of the peace or county courts to appoint patrollers, usually white men obligated to serve for a term in exchange for tax exemptions or other civic privileges.19

Patrollers typically operated in small, mounted bands, conducting nighttime sweeps through rural districts and along plantation roads. Their legal authority was sweeping: they could enter private homes, interrogate, whip, and detain enslaved persons at will.20 Patrols thus blurred the boundary between law and terror; their violence was not an aberration but an instrument of public order. As historian Sally Hadden observes, patrols “created a culture of surveillance and discipline that made every slave cabin a potential site of inspection.”21

In their design, slave patrols resembled a decentralized police force, organized locally, commanded by magistrates, and charged with enforcing statutory codes. Yet their purpose was not civic peace but racial submission. They policed not crime but condition. In their eyes, the mere mobility of a Black person constituted probable cause.22 To patrol was to assert the supremacy of whiteness and to reassert, nightly, the state’s complicity in bondage.

The Logic of Control and the Machinery of Fear

The patrol system operated through ritualized violence. Whippings were a standard, legally sanctioned form of discipline; the infliction of pain was viewed as preventive policing.23 Patrollers entered cabins unannounced, interrogated gatherings, and confiscated any tools, books, or weapons deemed suspect.24 This was not a marginal institution but a cornerstone of southern governance: public funds often subsidized weapons, horses, and uniforms, and patrol regulations were reviewed annually by county courts.25

The social composition of patrols reflected the hierarchical anxieties of the South. Wealthy planters often avoided active service, delegating the duty to poor and middling whites who saw in the patrol a means of asserting racial dominance.26 For these men, the uniform or badge of authority, however crude, offered symbolic compensation for their economic precarity. Policing Black bodies became a form of social belonging: a nightly rehearsal of whiteness and power.27

At its core, the patrol system sought not merely to prevent rebellion but to preserve the illusion of order. Fear of insurrection, particularly after events like Gabriel’s Rebellion in 1800 and Denmark Vesey’s alleged conspiracy in 1822, intensified patrol activity and expanded their authority.28 In effect, the entire southern countryside became a militarized space of surveillance, where law enforcement served the planter’s security rather than public justice.

Free Blacks, Mobility, and Legalized Suspicion

The patrol system did not distinguish clearly between enslaved and free African Americans. Free Blacks were required in many states to carry proof of manumission or “freedom papers,” and failure to produce such documents could result in arrest, flogging, or sale into bondage.29 Thus, even free persons lived under constant threat of detention. Their very existence exposed the contradictions of the slaveholding republic: legal freedom coupled with social captivity.

Cities such as Charleston and Richmond created municipal patrols or “guards” to police the movement of free and enslaved Blacks alike, imposing curfews and restricting gatherings after dark.30 As the urban slave population grew, these measures became increasingly systematic, effectively an early form of racialized policing in municipal form.31 Even in Washington, D.C., patrols employed by city commissioners enforced pass systems and punished violations with imprisonment or forced labor.32

The effect of this pervasive scrutiny was the internalization of surveillance: every movement by a Black person could attract inquiry, every absence provoke punishment. In this environment, “law enforcement” was synonymous with racial control, and resistance to the patrol system (whether through flight, subterfuge, or open defiance) became both a political and existential act.33

The Continuities of Policing and Race

The racial logic embedded in the slave patrols outlived the institution of slavery itself. When the first formal municipal police departments emerged in southern cities during the 1830s and 1840s, many of their personnel and practices were drawn directly from the patrol tradition.34 Their jurisdiction widened, but their racial assumptions remained. The habits of surveillance, suspicion, and coercive control that had been normalized in the patrolling of plantations became standard features of urban law enforcement.

Northern observers, noting the brutality of southern patrols, often used them as rhetorical evidence of the moral decay of slavery. Yet even in the North, the pattern of racialized enforcement persisted under different names: Black codes, vagrancy laws, and street regulations disproportionately applied to people of color.35 The structural kinship between slave patrols and later policing systems lay not merely in personnel or tactics but in ideology, the belief that certain populations required exceptional monitoring to preserve social order.

By mid-century, the United States had developed two intertwined legacies of enforcement: one grounded in republican suspicion of power, the other in racial domination. Together they forged the contradictory DNA of American policing, a system born both from the fear of tyranny and from the tyranny of fear itself.

Toward Professional Policing — Transition, Tensions, and Citizen Resistance (1830–1850)

Overview

By the 1830s, rapid urbanization and industrialization began to expose the limits of America’s inherited systems of local enforcement. Small towns were transforming into populous cities, fueled by waves of immigration, economic dislocation, and widening class divisions. The night watch and constable arrangements, built for agrarian communities, proved unequal to the rising complexity of urban life. The result was an intensifying debate about whether order could be maintained without sacrificing liberty. Out of that debate, the first professional police departments were born. Yet, in their emergence, citizens again recognized the familiar shadow of centralized power, now dressed in uniform.

Urban Growth and the Pressure of Disorder

In places like New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia, the 1830s witnessed frequent riots, strikes, and ethnic tensions.36 Political clubs, volunteer fire brigades, and street gangs often acted as quasi-militias aligned with local factions.37 Municipal governments, already struggling to administer sanitation, street lighting, and welfare, were ill-equipped to respond to such unrest. In New York alone, the 1834 anti-abolition riots, the 1837 Flour Riots, and the 1849 Astor Place Riot revealed how easily social grievances could erupt into violence.38

The old constabulary system, with its part-time watchmen and unpaid magistrates, collapsed under this pressure. Reformers, often merchants and property owners, called for a full-time, salaried, and disciplined police force that could patrol day and night.39 Their argument echoed the British model: after London’s Metropolitan Police had been established in 1829 under Sir Robert Peel, many American elites saw professional policing as a necessary modernization.40 But to others, the proposal carried the scent of monarchy. Newspapers decried it as “a standing army in disguise,” while workingmen and radicals warned that uniformed police would serve as the enforcers of wealth and repression.41

Boston, New York, and the Birth of the Municipal Police

Boston became the first American city to establish an organized, publicly funded police department in 1838.42 Though initially small and limited to the wharves and commercial districts, it introduced features that defined modern policing: salaried officers, regular shifts, and hierarchical command.43 New York followed with reforms in the 1840s, though its system remained entangled with local politics. The New York City Municipal Police, formally organized in 1845, operated under the control of city aldermen and ward bosses.44 Political patronage determined hiring and promotion, ensuring that the new “professional” police were as corrupt and partisan as the politicians they served.

This politicization quickly bred scandal. Reports circulated of officers accepting bribes, targeting labor organizers, and using excessive force against immigrants and the poor.45 The city’s working-class newspapers accused the new police of replacing civic duty with coercion, noting that “where once the watchman knew the faces of his neighbors, now an armed stranger keeps the peace by threat.”46 For many citizens, professionalization signified not progress but alienation, the substitution of bureaucracy for community.

Citizens’ Fears of State Power

These anxieties were not unfounded. Early police ordinances granted officers broad discretionary powers to detain individuals on suspicion alone, regulate street gatherings, and enforce vagrancy laws.47 The working poor, free Blacks, and recent immigrants were the principal targets. Even in northern cities that prided themselves on republican liberty, policing quickly acquired a class and racial dimension. In 1844, the New York Herald noted that “the police seem most active in the poorer wards, where a man’s poverty is itself suspicious.”48

Courts offered little recourse against police misconduct. The doctrine of “officer discretion” insulated many abuses from scrutiny, and municipal oversight boards often doubled as political machines.49 Citizens who protested arrests or challenged searches could find themselves charged with “disorderly conduct,” a vague offense that granted near-total authority to the arresting officer.50

The tension between liberty and order, so central to the American founding, thus resurfaced within the city streets. To many citizens, the uniformed policeman looked alarmingly like the standing army their ancestors had resisted. Even reformers sympathetic to policing recognized the danger. Boston’s mayor, Josiah Quincy Jr., admitted in 1848 that the city must “tread carefully, for in preserving order we risk stifling the freedom that gives order meaning.”51

Race, the Law, and the Expansion of Federal Enforcement

The rise of municipal police coincided with growing national conflict over slavery and the enforcement of fugitive slave laws. Federal marshals, empowered under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and later strengthened by the law of 1850, increasingly collaborated with local police to capture escaped slaves and suppress abolitionist resistance.52 In effect, the machinery of local law enforcement became an extension of the slave system, even in free states.

Northern citizens often viewed this cooperation as a violation of state sovereignty and moral conscience. When U.S. Marshals and Boston police arrested the fugitive Anthony Burns in 1854 (a few years beyond this essay’s central timeframe), the public outrage reflected sentiments already brewing in the 1840s.53 As historian Gary Potter observes, “policing in the antebellum North could not be disentangled from the racial politics of the nation.”54 Whether through patrols in the South or police actions in the North, the underlying logic was consistent: maintaining social order by controlling marginalized bodies.

Reform and Resistance

By the close of the 1840s, calls for accountability grew louder. Citizens’ associations demanded public oversight boards and limits on police discretion.55 Some cities experimented with complaint registries or required officers to wear numbered badges for identification.56 Yet the basic structure of coercive authority had been established. Once a city acquired a professional police, it rarely relinquished it. The state’s capacity to surveil, detain, and enforce had become normalized, ironically, in a republic still proclaiming its distrust of power.

Between 1830 and 1850, American law enforcement underwent a profound metamorphosis. The transformation was not linear nor universally accepted. It was contested in town halls, newspapers, and courtrooms; it was feared by workers and celebrated by merchants; it promised safety yet threatened autonomy. In that crucible, the modern American police took shape, not as a neutral instrument of order, but as a reflection of the nation’s unresolved struggle between liberty and control, equality and hierarchy.

The Citizen’s Wary Gaze — Themes of Rights, Resistance, and Legitimacy

Overview

By mid-century, the American experiment in liberty had come full circle. The young republic that once defined freedom as the absence of arbitrary power now found itself governed by systems increasingly reliant on it. Sheriffs, constables, watchmen, patrols, and police (each born of practical necessity) had collectively transformed the landscape of civic life. Yet, for ordinary citizens, especially those without property or privilege, these institutions often represented not the shield of justice but its weapon. The central paradox of American law enforcement was now fully exposed: the state that distrusted authority had created, step by step, the mechanisms of its own domestic coercion.

Rights Under Stress: Search, Seizure, and the Limits of Liberty

The Bill of Rights promised citizens protection against unreasonable searches, seizures, and the deprivation of liberty without due process.57 In practice, these guarantees were frequently suspended by the exigencies of “order.” Municipal ordinances empowered police and constables to detain individuals deemed vagrants or “disorderly persons” without formal warrant, a broad category that encompassed the poor, the drunk, and the politically inconvenient.58 Local courts often upheld such arrests as necessary exercises of police power, a doctrine increasingly invoked to justify nearly any encroachment upon personal freedom in the name of public welfare.59

This elasticity of law made abuse not exceptional but systemic. Arrests without cause, warrantless searches, and the use of summary punishment blurred the line between legal authority and personal vendetta. In Boston, for example, reformers complained that the new police “exercised a discretionary tyranny under the pretense of protecting peace.”60 The language of protection thus became the moral vocabulary of control. The same Constitution that limited federal intrusion now enabled local governments to intrude daily into the lives of their citizens, so long as it was done in the name of safety.

Political Control and the Machinery of Patronage

Nowhere was the potential for abuse clearer than in the political manipulation of law enforcement. In the great northern cities, policing was woven tightly into the fabric of urban patronage. Appointments were rewards for party loyalty; officers collected “contributions” for political campaigns; and arrests often targeted rival factions rather than actual criminals.61

The partisan nature of policing provoked both satire and protest. The New York Tribune observed in 1849 that “the constable’s truncheon is as much a party emblem as the banner of Tammany Hall.”62 Officers were expected to suppress opposition gatherings, disperse reform societies, and protect friendly mobs during elections.63 This corruption did not merely offend republican ideals; it eroded the fragile legitimacy of law itself. The citizen who perceived the constable as a political enforcer ceased to see him as the guardian of justice.

Southern law enforcement was no less politicized, though its object differed. There, the patrol and sheriff operated as the guardians of racial hierarchy.64 The abuse of authority was sanctioned not by political faction but by social order itself, legitimized through law and tradition. In both regions, the result was the same: law enforcement that answered upward to power rather than outward to the people.

Resistance, Reform, and the Discourse of Accountability

Despite these realities, citizens did not submit silently. Public resistance to abusive enforcement took many forms, from legal petitions and newspaper exposés to riots, lawsuits, and legislative reforms. In Philadelphia, free Black activists such as Robert Purvis and William Still documented cases of police harassment and kidnapping under fugitive slave pretenses, later using that evidence in abolitionist publications.65 In New York, working-class associations formed committees to monitor police conduct and publish annual “Black Books” cataloging misconduct.66

Some reformers sought institutional remedies. Civic groups demanded that officers be numbered for identification and required to appear before independent review boards when accused of misconduct.67 Others argued for professional training and merit-based hiring as antidotes to corruption.68 Yet such proposals met with fierce resistance from city politicians who feared losing control of patronage, and from conservative citizens who equated oversight with disorder.

At the rhetorical level, however, these reform movements helped redefine the relationship between citizens and state power. Newspapers and pamphlets revived revolutionary language, warning that “a government armed within its own streets is but the ghost of monarchy revived.”69 The suspicion that once targeted royal troops now fixed upon the domestic police. The difference was that the new enforcers spoke with the accent of one’s neighbor, not the king.

The Racial Fault Line and the Limits of Universal Rights

Nowhere did the contradiction between American ideals and American reality appear more starkly than in the racialized application of law. In both North and South, Black Americans faced a double jeopardy: excluded from full citizenship yet subject to the full coercive power of the state.70 In the South, this took the form of patrols and slave codes; in the North, it appeared in curfews, discriminatory arrests, and racialized vagrancy statutes.71

Northern police routinely targeted free Black communities for raids under the pretense of enforcing minor ordinances.72 When confronted, city officials defended such actions as “necessary to maintain order among a volatile class.”73 The persistence of this logic revealed the moral continuity between slavery and freedom: emancipation without equality still required enforcement.

For reformers like Frederick Douglass, this hypocrisy was intolerable. Writing in 1850, he argued that “the badge of the police is now what the whip was before; it strikes the Black man first.”74 His words captured the emerging recognition that racial hierarchy had become embedded not just in the social fabric but in the state’s mechanisms of control. Even as the republic celebrated its expansion westward, its systems of law enforcement mirrored the inequalities it refused to confront.

Liberty and Power in a Republic of Fear

By 1850, the line between freedom and enforcement had grown perilously thin. Citizens continued to debate whether the price of order was too high, but the apparatus of policing (once improvised, now institutional) was firmly established. What had begun as a local defense of communal peace had evolved into a professional bureaucracy capable of surveillance, detention, and coercion. For many, this transformation represented the unavoidable maturation of a modern nation-state; for others, it marked the betrayal of republican virtue.

The citizen’s wary gaze, however, never disappeared. From Boston’s wharves to Charleston’s plantations, Americans remained uneasy with those who bore the authority to enforce the law. They understood, instinctively, if not philosophically, that the same power that could protect could also destroy. In the shadow of that understanding, the modern American relationship to policing was born: a mixture of dependence and distrust, reverence and resentment, liberty guarded by the instruments that could most easily take it away.

Conclusion: Legacies, Ironies, and Scholarly Reflections

By 1850, the architecture of American law enforcement had been firmly established, but the spirit that animated it remained divided. What began as a set of pragmatic responses to local disorder had become a powerful apparatus of surveillance and control, an apparatus that citizens alternately feared, resisted, and relied upon. In the process, the republic had stumbled into a defining paradox: its people had built institutions to protect liberty that now threatened to confine it.

The first half of the nineteenth century thus stands as a hinge between two eras, the premodern world of communal watchfulness and the modern state of bureaucratic policing. In its early years, the republic mistrusted authority so deeply that it diffused enforcement through sheriffs, constables, and militias, ensuring that no single entity could monopolize coercive power.75 Yet, as population, commerce, and inequality grew, that very diffusion appeared inadequate. In their search for efficiency, Americans found themselves resurrecting the structures of command they had once despised. The emergence of salaried, uniformed police in the 1830s and 1840s marked the triumph of order over the fear of standing power, but it also marked the quiet erosion of the citizen’s supremacy over the state.

Nowhere was this erosion clearer than in the racial foundations upon which much of American enforcement had been built. The slave patrols of the South, with their legal sanction to interrogate, whip, and terrorize, revealed the extent to which liberty was never meant for all.76 Policing became the mirror through which the republic’s contradictions were reflected: a white democracy secured by Black subjugation, a free society dependent on surveillance and force. The patrol’s ideology, the conflation of danger with race, of order with domination, would persist long after slavery’s demise.77 In this sense, the racial logic of early policing was not an aberration but a constitutive element of American law itself.

Northern reformers often congratulated themselves for rejecting the brutality of southern patrols, yet their own cities bore subtler versions of the same injustice. The vagrancy laws that targeted free Blacks and the poor, the arbitrary arrests under “public order” statutes, and the discretionary violence of police batons all reproduced, under new symbols, the old assumption that some lives required restraint for the safety of others.78 As Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists recognized, the distinction between slavery and freedom was not one of law but of degree. A republic that tolerated racial policing in the name of stability was already betraying its founding principle: that government exists by consent of the governed.79

Historians have long debated whether these early forms of enforcement were necessary stages in the evolution of a modern state or evidence of an enduring failure to reconcile freedom with authority.80 The truth lies in the tension itself. The young republic’s distrust of centralized power did not vanish; it simply adapted, transforming into cycles of reform and backlash that continue to define American policing. Every generation since has revived the same questions voiced in 1838 Boston or 1845 New York: How much force may a free society tolerate? What safeguards make power legitimate? And who, in practice, is counted among the “citizens” that power exists to protect?

The legacy of early American law enforcement endures not only in institutions but in national temperament. The citizen’s wary gaze, formed in the crucible of revolution, slavery, and urban unrest, remains fixed upon the figure of authority. The tension between liberty and order, equality and control, is not a historical artifact but a living inheritance. The republic’s founders feared that tyranny might come marching in red coats; they did not foresee that it might arrive instead in blue.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

- Roger Lane, Policing the City: Boston, 1822–1885 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 12–15.

- William J. Novak, The People’s Welfare: Law and Regulation in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 71.

- Ibid., 73.

- Samuel Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform: The Emergence of Professionalism (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1977), 18.

- Gary Potter, “The History of Policing in the United States,” The Police Studies Journal 8, no. 2 (1985): 5–8.

- Lane, Policing the City, 17–19.

- Ibid., 21.

- James F. Richardson, Urban Police in the United States (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1974), 10.

- Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform, 23.

- Potter, “The History of Policing,” 6.

- Novak, The People’s Welfare, 76.

- David R. Johnson, Policing the Urban Underworld: The Impact of Crime on the Development of the American Police, 1800–1887 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1979), 29.

- Judiciary Act of 1789, ch. 20, 1 Stat. 73.

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 34.

- The Boston Gazette, July 3, 1821.

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 117–20.

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 3–4.

- Ibid., 15–18.

- South Carolina Slave Code, 1740, in Thomas R. R. Cobb, An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in the United States of America (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, 1858), 258–62.

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 23.

- Ibid., 30–33.

- Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Vintage, 1974), 598.

- Clayton E. Jewett and John O. Allen, Slavery in the South: A State-by-State History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004), 62.

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 45–46.

- Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 81.

- Ibid., 83.

- Douglas R. Egerton, Gabriel’s Rebellion: The Virginia Slave Conspiracies of 1800 and 1802 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 142.

- Ira Berlin, Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), 123.

- Walter J. Fraser Jr., Charleston! Charleston!: The History of a Southern City (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989), 211.

- Peter P. Hinks, To Awaken My Afflicted Brethren: David Walker and the Problem of Antebellum Slave Resistance (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 76.

- Clarence Lusane, Black History and Black Identity: A Call for a New Historiography (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 54.

- Camp, Closer to Freedom, 91.

- Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004), 35.

- Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008), 9–10.

- Lane, Policing the City, 27.

- Eric H. Monkkonen, Police in Urban America, 1860–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 14.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 33–35.

- James F. Richardson, Urban Police in the United States, 16.

- Clive Emsley, The English Police: A Political and Social History (London: Longman, 1996), 55.

- Boston Daily Atlas, June 4, 1838.

- Lane, Policing the City, 31.

- Ibid., 33–34.

- Richardson, Urban Police in the United States, 18–20.

- Johnson, Policing the Urban Underworld, 42.

- The Workingman’s Advocate (New York), February 12, 1847.

- Monkkonen, Police in Urban America, 17.

- New York Herald, August 23, 1844.

- Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform, 25.

- Ibid., 26.

- Josiah Quincy Jr., “Annual Message to the City Council of Boston,” January 1848, Boston City Documents, vol. 5 (Boston: Eastburn’s Press, 1848), 12.

- Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 14–16.

- Ibid., 29–30.

- Gary Potter, “The History of Policing in the United States,” EKU School of Justice Studies (2013).

- Lane, Policing the City, 45.

- Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform, 27.

- U.S. Constitution, Amendment IV.

- Johnson, Policing the Urban Underworld, 58.

- Novak, The People’s Welfare, 97.

- Boston Courier, October 2, 1843.

- Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform, 31.

- New York Tribune, August 14, 1849.

- Monkkonen, Police in Urban America, 18.

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 112.

- Campbell, The Slave Catchers, 47.

- Potter, “The History of Policing in the United States,” 13.

- Lane, Policing the City, 47.

- Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform, 35.

- The Liberator, March 15, 1845.

- Berlin, Slaves Without Masters, 203.

- Hinks, To Awaken My Afflicted Brethren, 79.

- Fraser, Charleston! Charleston!, 221.

- Boston Daily Bee, November 11, 1847.

- Frederick Douglass, “The Claims of the Negro, Ethnologically Considered,” The North Star, April 1850.

- Novak, The People’s Welfare, 104.

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 173.

- Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name, 12.

- Johnson, Policing the Urban Underworld, 81.

- Douglass, “The Claims of the Negro, Ethnologically Considered.”

- Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform, 40–42.

Bibliography

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Berlin, Ira. Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South. New York: Pantheon Books, 1974.

- Bernstein, Iver. The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books, 2008.

- Camp, Stephanie M. H. Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Campbell, Stanley W. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

- Cobb, Thomas R. R. An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in the United States of America. Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, 1858.

- Douglass, Frederick. “The Claims of the Negro, Ethnologically Considered.” The North Star, April 1850.

- Egerton, Douglas R. Gabriel’s Rebellion: The Virginia Slave Conspiracies of 1800 and 1802. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Emsley, Clive. The English Police: A Political and Social History. London: Longman, 1996.

- Fraser, Walter J., Jr. Charleston! Charleston!: The History of a Southern City. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989.

- Genovese, Eugene D. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage, 1974.

- Hadden, Sally E. Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Hinks, Peter P. To Awaken My Afflicted Brethren: David Walker and the Problem of Antebellum Slave Resistance. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

- Jewett, Clayton E., and John O. Allen. Slavery in the South: A State-by-State History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

- Johnson, David R. Policing the Urban Underworld: The Impact of Crime on the Development of the American Police, 1800–1887. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1979.

- Lane, Roger. Policing the City: Boston, 1822–1885. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Lusane, Clarence. Black History and Black Identity: A Call for a New Historiography. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004.

- Monkkonen, Eric H. Police in Urban America, 1860–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Novak, William J. The People’s Welfare: Law and Regulation in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Potter, Gary. “The History of Policing in the United States.” EKU School of Justice Studies (2013).

- Quincy, Josiah Jr. “Annual Message to the City Council of Boston.” In Boston City Documents, vol. 5. Boston: Eastburn’s Press, 1848.

- Richardson, James F. Urban Police in the United States. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1974.

- Walker, Samuel. A Critical History of Police Reform: The Emergence of Professionalism. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1977.

- Williams, Kristian. Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.08.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.