Contemporary societies, equipped with vastly more sophisticated systems of governance, continue to wrestle with the same moral arithmetic.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

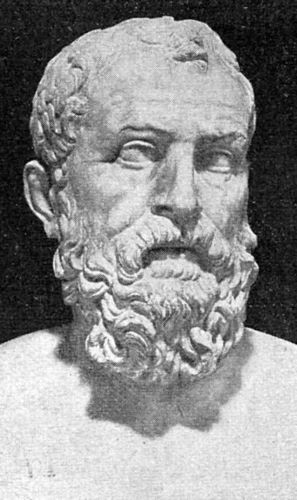

When the Athenian statesman Solon was granted extraordinary powers to resolve the deep economic crisis of 594 BCE, his city teetered on the edge of revolution. The vast inequalities of land and wealth had created a social order so brittle that the poorest citizens, enslaved for debt, could scarcely be called free men. Solon’s solution, the seisachtheia, or “shaking off of burdens,” would cancel all debts, abolish debt-slavery, and restore land to its rightful owners. It was a radical moment in the early history of political economy, a legislative act that placed justice above contract and human dignity above property. Yet in the shadows of this noble intent, corruption found opportunity. Before Solon’s decree was enacted, certain of his associates, privy to the secret of his coming reforms, took out large loans and purchased land, only to profit when the debts were annulled. Solon himself refused to benefit, but the moral stain of insider exploitation clung to his revolution like smoke over the altar of justice.1

The episode exposes one of the oldest paradoxes of reform: that even the most visionary acts of governance are vulnerable to the manipulations of those closest to power. Athens entrusted Solon to balance mercy and order, freedom and stability, but his very success invited duplicity. In ancient sources, such as Aristotle’s Athenian Constitution and Plutarch’s Life of Solon, the event is portrayed not as a scandal of greed alone but as a lesson in the fragility of moral authority when knowledge becomes capital.2 This tension between lawgiver and opportunist, between the spirit of reform and the exploitation of reform, would echo through centuries of political and financial history.

Solon’s Athens thus offers more than a study in antiquarian curiosity. It reveals a structural truth about human societies: that the instruments of justice can be turned into tools of profit when the few are allowed to act upon information denied to the many. The moral breach his contemporaries witnessed has become an enduring feature of economic systems from the Aegean to Wall Street. The debt-cancellation scandal, though ancient, speaks directly to the anatomy of insider advantage that pervades modern capitalism. Whether in the agora or the stock exchange, the logic remains the same—those who hear first, profit first.3

What follows will trace this pattern across time. Beginning with the economic and political conditions that led to Solon’s reforms, it will examine the seisachtheia itself as both a legal innovation and a moral statement. It will then analyze how the incident of insider exploitation illustrates a fundamental flaw in systems of reform, the inevitable gap between intention and execution, between justice proclaimed and profit seized. Finally, it will follow this thread into the modern age, revealing how the ancient Athenian paradox survives wherever elite access meets public policy. From Solon’s day to our own, the same drama unfolds: the lawgiver’s dream betrayed by the profiteer’s whisper.

Athens Before Solon: Crisis, Debt, and Class Strain

Before Solon’s appointment as archon, Athens was a society fractured by wealth, debt, and desperation. The sixth century BCE opened upon a polis in which economic disparity had reached unbearable extremes. A small elite of eupatridae (hereditary aristocrats) controlled most of the arable land, while the majority of small farmers survived precariously, mortgaging their property to these same creditors. The legal structure reinforced inequality: debts were secured not merely by land but by the person of the debtor. Many Athenians, unable to meet payments, became hektemoroi, obligated to surrender one-sixth of their produce to landlords who now effectively owned them. Others, trapped by compounding obligations, were sold abroad as slaves. The city was, as Aristotle wrote, “divided between the few and the many,” its social fabric strained to the breaking point.4

The crisis was not simply economic but moral and civic. Athens faced what Victor Ehrenberg described as a “pre-democratic revolution,” a moment when political authority risked collapsing beneath the weight of social injustice.5 The demos (the common people) threatened revolt, while the aristocracy feared that their dominance might dissolve in chaos. Out of this stalemate emerged the call for a mediator who could reconcile justice with stability. Solon, celebrated for both wisdom and integrity, was chosen to avert civil war through reform rather than repression. His appointment marked a rare moment in antiquity when political trust was extended not to lineage or divine right, but to reputation for fairness.

The burden Solon inherited was immense. He faced a city on the verge of dissolution, its citizens divided by resentment and despair. Debt-slavery had eroded the ideal of citizenship itself, for those enslaved could neither vote nor defend their polis. The social hierarchy of Athens, which once rested upon shared obligations of community, had hardened into a system of predation.6 Solon’s poetry, fragmentary though it is, captures this despair:

“Our city will never perish by the decree of Zeus; but her own citizens, through their folly, seek to destroy her.”7

The lines reveal a profound awareness that corruption, not foreign invasion, threatened Athens most deeply.

By 594 BCE, Athens stood poised between oligarchic tyranny and social revolution. Solon’s challenge was to rescue both liberty and order without surrendering to either extreme. His response, the seisachtheia, would “shake off the burdens” of debt and restore a measure of equality. Yet in doing so, it would also expose how reform, even when born of justice, could become an avenue for the very exploitation it sought to end. That contradiction, forged in the crucible of Athenian crisis, remains one of the oldest moral dilemmas in the history of governance.8

The Seisachtheia: Law, Reform, and Immediate Consequences

Solon’s reforms, collectively known as the seisachtheia, literally the “shaking off of burdens,” represented one of the most consequential social and legal transformations in the history of the ancient polis. His decrees eliminated all debts secured upon the person, canceled existing mortgages marked by horoi (boundary stones), and prohibited the future enslavement of citizens for debt.9 The law ordered the manumission of those already sold into servitude, and as Plutarch recounts, Solon even arranged for many Athenians who had been enslaved abroad to be brought home.10 For the first time, the citizen body of Athens was reconstituted upon a foundation of legal freedom, rather than economic dependence.

The immediate effects were dramatic. The creditors, largely members of the landed elite, denounced the measures as confiscatory and unjust; the impoverished masses, having expected redistribution of land, accused Solon of betraying their hopes. In his own verse, he defended his actions as a deliberate middle course:

“I stood with my mighty shield before both parties, and did not permit either to prevail unjustly.”11

The policy exemplified his ideal of metriotes (moderation), a concept he regarded as the moral mean between excess and deficiency. Yet in his moderation lay a subtle irony. By revealing his intention only upon enactment, Solon created a window in which privileged information could be weaponized for profit.

According to both Aristotle and Plutarch, certain of Solon’s associates, forewarned of his plans to abolish debts, hurried to borrow vast sums and purchase land shortly before the decree was proclaimed.12 When the seisachtheia was enacted, their debts vanished, leaving them owners of estates obtained at no cost. Solon’s reputation for integrity survived because he refused to participate, but the incident became one of the earliest recorded examples of economic manipulation through insider knowledge. In the language of modern ethics, it was the first “information asymmetry scandal.” The irony was unmistakable: the lawgiver who sought to purify Athens from corruption had inadvertently provided new means for corruption to flourish.

The scandal’s repercussions extended beyond mere economics. It struck at the very legitimacy of reform itself. Aristotle’s Athenian Constitution portrays Solon as lamenting the backlash that followed, declaring that both rich and poor “maligned him unjustly.”13 His ideal of justice depended on transparency and shared sacrifice, yet his reforms had revealed how unevenly information, and therefore power, was distributed in Athenian society. Those closest to the levers of governance could anticipate, adapt, and ultimately profit from measures meant to restore fairness. That paradox, reform as both remedy and opportunity, would become a recurring motif in the history of legislation.

Still, Solon’s achievement cannot be dismissed as naïve idealism undone by greed. The seisachtheia redefined Athenian citizenship by detaching legal status from economic bondage.14 It restored civic participation to those who had been silenced by debt, making possible the later political evolution toward democracy. The abuse of inside information, while corrosive, could not erase the structural transformation he initiated. In abolishing debt-slavery, Solon forced Athens to confront the moral cost of profit built upon the suffering of fellow citizens, a question that echoes through every subsequent age of reform.

Knowledge as Capital: The Moral Dimension of Inside Information

The scandal surrounding Solon’s reforms did more than expose opportunism; it illuminated a deeper truth about the relationship between knowledge and power in civic life. In Athens, where citizenship was a sacred trust and the polis a moral community, the possession of privileged information became a form of capital as potent as land or silver. To know the law before it was law was to command the economy of an entire city. In this sense, Solon’s dilemma anticipated a principle that has never ceased to haunt democratic societies: when governance depends upon the discretion of a few, even reform itself can become a marketable commodity.15

Solon himself seemed acutely aware of the moral stakes. His surviving poetic fragments, preserved by later writers, oscillate between pride in his justice and sorrow at human greed. In one, he writes that “the citizens themselves, through their folly, bring great ruin upon their city,” a lament not of divine wrath but of civic failure.16 For Solon, injustice (adikia) was not merely a social ill but a spiritual disorder, an imbalance of dike (justice) that eroded the harmony of the whole community. His choice to forgo personal profit was thus more than political restraint; it was an act of ethical purification, a statement that virtue required detachment from gain. Yet the betrayal of that ideal by his associates demonstrated how virtue alone could not safeguard justice in the absence of institutional transparency.

The moral tension embedded in the seisachtheia, between private interest and public good, reverberated throughout Greek political thought. Hesiod’s Works and Days, composed a century earlier, had already warned that corrupt judges “devour the bribes of the unjust,” a reflection on how moral failure corrodes civic life from within.17 Solon’s reforms gave that warning legal form. His Athens was attempting, perhaps for the first time, to legislate fairness itself. But fairness, when filtered through unequal access to information, became merely another vector of advantage. The philosopher’s paradox was born: justice cannot exist where ignorance is systemic and knowledge is hoarded by the few.

Later thinkers would recognize this paradox as a recurring flaw of governance. Aristotle, reflecting on Solon two centuries later, observed that even good laws cannot restrain the corrupting influence of self-interest unless sustained by civic virtue.18 Josiah Ober, in his modern analysis of Athenian democracy, argues that Athens’ later institutions (public deliberation, open archives, and citizen juries) were deliberate responses to the failures exposed in Solon’s time.19 The very birth of democracy, in this sense, can be read as Athens’ attempt to democratize knowledge, to ensure that no one man or faction could again profit secretly from the fate of all.

Solon’s tragedy, then, lies not in his failure but in his foresight. He recognized that moral reform must contend not only with laws and institutions but with human nature itself, the appetite for advantage disguised as prudence, and the capacity for betrayal beneath the mask of friendship. Knowledge had become the new coin of the realm, and in every age since, it remains the most potent currency of power.20

Structural Continuity: From Athenian Reform to Modern Economic Manipulation

The story of Solon’s seisachtheia does not end with antiquity. Its pattern, the exploitation of reform by those closest to power, has repeated itself through every age of economic transformation. The principle remains constant: when information precedes law, advantage precedes justice. The Athenian elites who used Solon’s secret to cancel their debts were forerunners of a lineage that stretches through the mercantile empires of early modern Europe, the speculative manias of the eighteenth century, and the financial crises of the modern global economy. What began as a civic lesson in moral restraint evolved into a structural truth of capitalism itself, the system rewards those who act before others can know.²¹

The eighteenth century provided one of the clearest analogues to the Athenian precedent in the career of John Law, the Scottish economist who engineered France’s infamous Mississippi Scheme of 1719–1720. Law’s grand experiment in debt conversion and colonial speculation promised to stabilize France’s finances after the reign of Louis XIV. Yet insiders (nobles, courtiers, and financiers with early access to information) profited immensely before the bubble burst. The public, trusting in reform, was left ruined.²² The episode mirrored Solon’s dilemma in a modern key: economic reform conceived as salvation devolved into exploitation through asymmetric knowledge. The moral vocabulary had changed, but the mechanics of advantage had not.

Modern markets have only refined the Athenian principle. During the 1929 crash and the 2008 financial crisis, the concentration of financial knowledge in the hands of a few proved decisive. The same insider dynamic that plagued Solon’s Athens recurred on a global scale. Liaquat Ahamed’s study of the interwar central bankers, the self-styled “Lords of Finance,” reveals how their private communications shaped entire national economies while the public bore the cost of their misjudgments.²³ Robert Shiller’s analysis of speculative exuberance in the early twenty-first century echoes this diagnosis: reform, regulation, and stimulus policies intended to stabilize markets often served those positioned to anticipate them.²⁴ What Solon faced on the Athenian agora, modern economists confront in the algorithms of Wall Street.

Yet the continuity is not merely financial; it is moral and structural. Every reform movement generates, by its very secrecy and timing, an insider class, those informed early enough to profit or shield themselves. The logic of insider advantage is therefore embedded within reform itself. Transparency, though often hailed as a safeguard, remains imperfect because legislation must first be conceived, drafted, and approved before it can be disclosed. Between those stages lies the vulnerable interval where knowledge becomes capital.²⁵ In this sense, the ethical failure of Solon’s companions foreshadowed a permanent dilemma of governance: the impossibility of absolute equality where knowledge is sequential rather than simultaneous.

Economists such as Charles Kindleberger have shown how this dynamic produces recurrent cycles of “manias, panics, and crashes.”²⁶ In every age, from the South Sea Bubble to the digital currency markets of the present, speculative elites translate foresight into fortune while the majority experience reform as aftershock. The resilience of this pattern suggests that economic exploitation is less an aberration of policy than a consequence of human behavior under conditions of unequal access. Athens’ struggle was not unique; it was the prototype of a moral economy perpetually vulnerable to its own cleverness.

If Solon’s Athens marked the birth of legislative reform, our modern world represents its industrialization. Governments and markets now operate on information systems so vast that the distinction between reformer and profiteer can vanish entirely. The insider, once a friend at court, is now an algorithm trading in microseconds. Yet the ethical question remains identical to that which faced Solon in 594 BCE: can justice survive the speed of profit? The persistence of insider exploitation across millennia suggests that laws alone cannot equalize knowledge, and that the promise of reform will always contend with the ingenuity of self-interest. In this continuity lies the tragedy of progress, the advancement of civilization without the advancement of virtue.²⁷

The Legacy of Solon: Lawgiver, Idealist, and Reluctant Realist

Solon’s reputation as the founder of Athenian justice endures precisely because his reforms were both visionary and flawed. He was neither the utopian his admirers imagined nor the cynic his critics accused him of being. His legacy rests in his willingness to legislate against the instincts of his own class, to privilege civic harmony over private advantage. Yet even as he codified equality before the law, his experience revealed how fragile that equality could be when law itself became a vessel for profit. The same seisachtheia that freed the poor also enriched the cunning. His Athens learned, and the world after him would relearn, that corruption thrives not in tyranny alone but also in freedom unguarded by vigilance.28

Plutarch’s portrait of Solon captures the duality of this legacy. He describes a man who, after finishing his reforms, left Athens voluntarily for ten years to avoid pressure to alter his laws.29 That self-imposed exile symbolized more than political prudence; it was a withdrawal from the corrupting intimacy between lawgiver and those who would twist his laws for gain. Solon understood that proximity to power is perilous to virtue. In leaving Athens, he preserved the moral authority of his reforms, even as he acknowledged their imperfect execution. His departure reads almost like a philosophical retreat, a recognition that justice, once released into the world, must contend with forces beyond its author’s control.

In the centuries that followed, Solon became a moral archetype: the wise legislator whose integrity outlives his legislation. Aristotle credited him with “laying the foundations of democracy,”30 while later thinkers from Cicero to Montesquieu invoked his name as a model of enlightened moderation. Yet this admiration often obscured the irony at the heart of his story, the fact that his reforms were exploited even before they took effect. The legend of Solon, polished by generations of moralists, concealed the uneasy truth that good laws can generate new forms of inequality. In this sense, his failure was as instructive as his success.

The persistence of insider exploitation across history lends Solon’s example a modern resonance. Contemporary societies, equipped with vastly more sophisticated systems of governance, continue to wrestle with the same moral arithmetic. Whistleblower laws, financial disclosure requirements, and corporate transparency statutes all reflect the ancient realization that justice cannot survive secrecy. Yet these measures, too, depend on the virtue of those who enforce them. The tension between ideal and practice remains unresolved. What Solon confronted on the Pnyx, lawmakers now face in parliaments and trading floors around the world: the perpetual collision between moral aspiration and human avarice.31

Solon’s legacy, therefore, is not the perfection of justice but its pursuit. His reforms inaugurated a tradition in which law serves both as a mirror and as a restraint upon human nature. The Athenians called him nomothetes (lawgiver) but his true contribution was philosophical rather than merely legal. He revealed that justice is not an equilibrium achieved once and for all but a struggle continually renewed against the ingenuity of exploitation.32 In that struggle, the modern world remains Athenian. The insiders still whisper, the markets still stir, and the lawgiver still walks alone, searching for a balance between mercy and truth.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 6.11; Plutarch, Solon 15–17.

- Alain Duplouy, “The So-Called Solonian Property Classes Citizenship in Archaic Athens,” Annales HHS Vol. 69, No. 3 (2014): 411-439.

- Kurt Raaflaub, The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 88–93.

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 2–6.

- Victor Ehrenberg, From Solon to Socrates: Greek History and Civilization during the Sixth and Fifth Centuries B.C. (London: Routledge, 1968), 22.

- Paul Millett, Lending and Borrowing in Ancient Athens (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 14–19.

- Solon, Fragments, in Poetae Elegiaci Graeci, ed. Martin L. West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), fr. 4.

- Duplouy, “The So-Called Solonian Property Classes Citizenship in Archaic Athens.”

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 6.1–3.

- Plutarch, Solon 15.4–6.

- Solon, Fragments, in Poetae Elegiaci Graeci, fr. 5.

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 6.12; Plutarch, Solon 17.2–4.

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 12.

- A.R. Hands, Charities and Social Aid in Greece and Rome (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1968), 9–11.

- Josiah Ober, Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 44–47.

- Solon, Fragments, in Poetae Elegiaci Graeci, fr. 4.

- Hesiod, Works and Days 213–285.

- Aristotle, Politics II.1274a–b.

- Ober, Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens, 63–65.

- Kurt A. Raaflaub, The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 93–95.

- Raaflaub, The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece, 96–100.

- Charles P. Kindleberger, Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises (New York: Basic Books, 1978), 57–63.

- Liaquat Ahamed, Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World (New York: Penguin, 2009), 112–118.

- Robert J. Shiller, Irrational Exuberance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 143–148.

- Ober, Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens, 70–73.

- Kindleberger, Manias, Panics, and Crashes, 25–27.

- Duplouy, “The So-Called Solonian Property Classes Citizenship in Archaic Athens.”

- John H. Finley Jr., Politics in the Ancient World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 41–45.

- Plutarch, Solon 25–27.

- Aristotle, Politics II.1274a–b.

- Raaflaub, The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece, 102–105.

- Duplouy, “The So-Called Solonian Property Classes Citizenship in Archaic Athens.”

Bibliography

- Ahamed, Liaquat. Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Aristotle. Athenian Constitution. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935.

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932.

- Duplouy, Alain. “The So-Called Solonian Property Classes Citizenship in Archaic Athens.” Annales HHS Vol. 69, No. 3 (2014): 411-439.

- Ehrenberg, Victor. From Solon to Socrates: Greek History and Civilization during the Sixth and Fifth Centuries B.C. London: Routledge, 1968.

- Finley, John H., Jr. Politics in the Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Hands, A.R. Charities and Social Aid in Greece and Rome. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1968.

- Hesiod. Works and Days. Translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. New York: Basic Books, 1978.

- Millett, Paul. Lending and Borrowing in Ancient Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Plutarch. Lives: Solon. In Parallel Lives. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A. The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Shiller, Robert J. Irrational Exuberance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Solon. Fragments. In Poetae Elegiaci Graeci, edited by Martin L. West. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.