The crisis of unemployment during the Great Depression transformed the relationship between American workers and the federal government.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

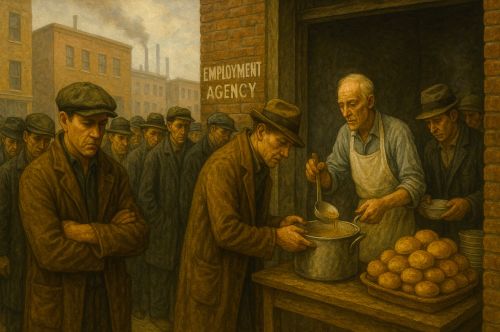

The collapse of the American labor market during the Great Depression exposed deep structural weaknesses in the national economy and forced a reconsideration of the federal government’s responsibility to protect its citizens. By 1933 unemployment had reached an estimated peak of roughly twenty five percent, with more than 12.8 million Americans out of work according to later reconstructions by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.1 The United States did not yet maintain a systematic national system for tracking unemployment, which meant that the crisis was measured unevenly in real time and later reconstructed by economists and historians using payroll records, census materials, and contemporary surveys. The scale of the breakdown stood without precedent in American history and shaped the trajectory of federal policy for decades to come.2

The consequences of this labor collapse extended far beyond economic statistics. Families experienced rapid declines in income, depletion of savings, and the collapse of community networks that had functioned for generations as informal support systems. Some households fractured under strain as family members left home in search of work, creating new patterns of mobility across the country. These movements included long distance searches for temporary agricultural labor, internal migrations from industrial centers into surrounding counties, and regionally specific relocations such as the westward movement from drought stricken parts of the Great Plains. Contemporary letters, oral histories, and relief agency records document the anxiety, humiliation, and dislocation experienced by millions who confronted long term joblessness.3

The magnitude of the crisis stemmed from a convergence of domestic and global forces. Deflation reduced consumer spending as households delayed purchases in the expectation of future price declines. International trade contracted sharply after the Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 provoked retaliatory measures abroad that restricted markets for American goods.4 The Federal Reserve raised interest rates in an effort to protect the gold standard, a decision that contributed to monetary contraction and reduced business investment. Economic historians have shown that each of these forces exerted downward pressure on employment and that their combined impact produced a cascading sequence of industrial, agricultural, and commercial failures that overwhelmed local relief systems.5

When Franklin D. Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1933, the federal government confronted a level of unemployment that state and municipal institutions could no longer manage. Early New Deal programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Civil Works Administration provided immediate work relief, while the Federal Emergency Relief Administration expanded direct aid to households.6 These efforts marked a turning point in the federal role in labor markets and created an administrative framework for later social policies. The Social Security Act of 1935 established the first national system of unemployment compensation, linking federal oversight to state administration and setting a precedent for long term federal responsibility.7 Roosevelt’s policies did not eliminate unemployment entirely, but they reshaped national expectations regarding public responsibility during economic crises.

Full recovery required a different scale of government expenditure that emerged only with the onset of global war. Rearmament and wartime mobilization in the late 1930s and early 1940s generated levels of federal spending that sharply reduced joblessness and eventually produced labor shortages across key industries.8 The shift from mass unemployment to full employment confirmed that the crisis had been rooted in a collapse of aggregate demand rather than individual failings. These transformations altered the political and economic landscape of the United States and shaped the design of postwar social policy.

Measuring Unemployment before and during the Crisis

The United States entered the Great Depression without a standardized national system for measuring unemployment, which meant that contemporary observers struggled to grasp the full scale of joblessness. Economists later reconstructed unemployment levels using census materials, payroll records, and industry surveys, most famously in the statistical series developed by Stanley Lebergott.9 These retrospective figures became the basis for the Bureau of Labor Statistics historical unemployment series, although Christina Romer later reexamined Lebergott’s methodology and argued that some early estimates overstated unemployment by misclassifying short term or irregular work.10 Their debate highlighted the difficulty of reconstructing a national labor crisis from incomplete or inconsistent data.

Contemporary reports from the Hoover administration painted a far less accurate picture. Federal officials relied heavily on voluntary employer surveys and state labor bureau submissions, which often underreported employment reductions because employers had little incentive to disclose the full extent of layoffs. Relief agencies, including the President’s Emergency Committee for Employment, tracked applicants seeking assistance, but their totals excluded many unemployed workers who never sought public aid.11 These discrepancies required later historians to reconcile administrative records with broader demographic data drawn from the 1930 and 1940 federal censuses, as well as from industrial surveys issued by the Department of Commerce.

One of the most significant blind spots in early measurement was underemployment, which affected workers who lost full time positions and found only sporadic or part time work. Construction, transportation, and retail jobs were particularly vulnerable, and many workers shifted between temporary positions that never appeared in federal reports. Case files preserved by state relief agencies reveal families attempting to survive on unstable income from irregular day labor.12 Community studies from the early 1930s, including investigations supported by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, show that widespread underemployment sharply reduced consumer demand even among households with some access to work.

Despite these obstacles, the statistical reconstructions produced by BLS and leading scholars remain indispensable for understanding the trajectory of the Depression. They show a rapid escalation of unemployment after the crash, a prolonged plateau of high joblessness through the mid-1930s, and a gradual decline that still left millions out of work by the end of the decade. These findings helped drive the federal government’s eventual creation of more consistent labor reporting systems and contributed to the institutional reforms that shaped modern employment measurement in the 1940s.13

Economic Factors Behind Mass Unemployment

The economic collapse that produced unprecedented joblessness during the Great Depression emerged from a convergence of interrelated forces that undermined production, spending, and investment across the country. Deflation intensified the downturn by encouraging households to postpone purchases in the belief that prices would continue to fall. This pattern is evident in contemporary commodity and retail price indexes, which show sustained declines between 1929 and 1933.14 As demand contracted, businesses faced shrinking revenues, reduced output, and mounting inventories, which in turn prompted layoffs that deepened the crisis.

International trade disruption further weakened industrial employment. The passage of the Smoot Hawley Tariff Act in 1930 raised American tariffs to historically high levels, prompting retaliatory measures from major trading partners.15 Export dependent industries, including agriculture, machinery, and metals, saw contracts disappear as foreign markets constricted. Congressional debates from 1929 to 1930 reveal warnings from economists and business leaders that higher tariffs would provoke global retaliation, and subsequent trade data from the Department of Commerce confirm a sharp decline in exports after the law went into effect. These losses directly affected industrial regions that relied on international markets to sustain employment.

Monetary contraction compounded these pressures. In an effort to defend the gold standard, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates in 1931 at precisely the moment when businesses and banks required greater liquidity.16 Higher rates discouraged borrowing, tightened credit, and accelerated failures among already weakened financial institutions. The Federal Reserve’s own annual reports from the early 1930s show a consistent prioritization of gold outflows over domestic stabilization, a policy orientation that restricted credit even as unemployment rose. Economic historians have demonstrated that monetary contraction significantly reduced output and increased the severity of the downturn.

Industrial dislocation also extended into agriculture, where falling prices and reduced demand undermined farm incomes across the Midwest, South, and Great Plains. Farmers who had borrowed heavily during the 1920s struggled to service debts as crop prices collapsed, leading to widespread foreclosures and farm abandonment. Records from the Department of Agriculture document substantial declines in farm commodity prices and note the growing distress among rural households during the early 1930s.17 As agricultural purchasing power shrank, rural communities reduced spending on manufactured goods, deepening declines in both urban and rural employment.

Each of these forces interacted to create a downward spiral in production and employment. Deflation reduced consumer spending, which cut industrial output. International retaliation constricted exports, weakening industries that relied on foreign markets. Monetary contraction tightened credit, limited investment, and accelerated business failures. Agricultural collapse reduced rural incomes and further limited demand for manufactured goods. Together these developments created a chain reaction that overwhelmed local authorities and revealed the need for national intervention.18

Social and Emotional Consequences of Joblessness

Unemployment during the Great Depression produced widespread psychological strain that reshaped family life, community structures, and individual identity. Diaries, letters, and relief case files reveal that many Americans experienced unemployment as a profound loss of dignity and purpose. Federal Writers’ Project interviews collected during the 1930s describe workers who had been stable wage earners confronting long periods of uncertainty and humiliation as they searched for work that no longer existed.19 These testimonies show that joblessness threatened not only financial stability but also the sense of self that many workers had long anchored in their productive roles.

The emotional burden of unemployment often fell unevenly within households. Many married women took on informal or temporary work to supplement income, even in communities where employers favored male hiring. Social workers documented rising levels of domestic conflict as financial pressures accumulated, and case records from urban relief agencies record instances of family separations prompted by prolonged joblessness.20 Some families sent children to relatives or charitable institutions when they could no longer provide basic necessities. These decisions appeared throughout the files of the Children’s Bureau, which observed increasing requests for assistance from households that had never sought public aid before the Depression.

Housing instability became another defining feature of the crisis. As savings evaporated and credit tightened, families unable to maintain rent or mortgage payments moved into makeshift dwellings or joined extended kin. Photographs produced by the Farm Security Administration show improvised settlements on the edges of major cities, commonly referred to as Hoovervilles, which housed unemployed workers, migrants, and families living on relief.21 These improvised communities varied widely in size and organization, but they shared a common origin in the widespread inability of households to secure stable shelter during prolonged periods of unemployment.

Migration became an essential survival strategy for many who sought temporary or seasonal work across the country. Some traveled by freight train in search of agricultural or industrial employment that was rumored to be available in distant regions. Contemporary reports from state police and local governments describe thousands of transient workers moving along rail lines, creating what officials sometimes called “the floating labor population.”22 Rural families in drought stricken regions of the Great Plains relocated westward, hoping to find more stable employment in California’s agricultural sector. Although popular memory often associates these migrations exclusively with Dust Bowl refugees, the broader movement included unemployed workers from across the Midwest and South.

The collapse of employment also strained traditional community networks that had previously provided informal support. Churches, mutual aid societies, and fraternal organizations attempted to meet rising needs but quickly became overwhelmed as the numbers of unemployed grew. Records of urban welfare agencies show that charitable organizations depleted their resources within months of the 1929 crash and appealed to municipal governments for assistance.23 The rapid exhaustion of private relief underscored the scale of economic distress and revealed the limits of local capacity in the face of nationwide unemployment.

Despite these hardships, unemployed workers and their families developed new forms of collective action. Local associations organized demonstrations, petition drives, and rent strikes in response to evictions and service shutoffs. The Unemployed Councils, associated with the Communist Party, mobilized tens of thousands of jobless workers in protests that demanded expanded relief and fair treatment from authorities.24 Although these movements varied in size and influence, they expressed the growing conviction that unemployment was a structural failure requiring public intervention rather than a private misfortune to be endured alone.

Local and State Relief Before the New Deal

Before the federal government assumed a central role in relief, local and state authorities attempted to manage a crisis whose scale exceeded anything they had previously encountered. Municipal governments relied on tax revenues that collapsed as businesses failed and property values declined, leaving cities unable to fund growing demand for assistance. Minutes from city councils in Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago show officials repeatedly warning that relief funds would be exhausted within weeks.25 State governments, constrained by balanced budget requirements and limited borrowing capacity, issued emergency appropriations but often did so reluctantly, fearing long term fiscal instability. As unemployment mounted, these early efforts proved insufficient to meet rapidly expanding needs.

Private charities faced even greater strain. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and local relief societies had long provided emergency assistance, but they relied on donations that fell sharply after 1929. Case records from the Charity Organization Society in New York indicate that requests for food, rent aid, and fuel increased far beyond what private agencies could provide.26 Many relief societies adopted stricter eligibility requirements in an attempt to ration limited resources, which excluded numerous unemployed workers who had previously relied on charitable support. These decisions generated significant public resentment and contributed to rising pressure for broader government involvement.

The Hoover administration encouraged voluntary cooperation and urged local communities to organize committees to assist the unemployed. The President’s Emergency Committee for Employment attempted to coordinate these initiatives by gathering data and encouraging private fundraising campaigns, but it lacked authority and financial resources to direct large scale relief.27 Reports from the committee reveal that many communities were already overwhelmed by early 1931 and that voluntary action could not sustain relief efforts as unemployment grew. Hoover maintained that direct federal aid would undermine local responsibility, a position that became increasingly untenable as the crisis deepened.

By 1932 the shortcomings of local and state relief were evident nationwide. Municipal shortages forced widespread cuts in assistance, and state legislatures reported that emergency appropriations were insufficient to stabilize households facing long term unemployment.28 The inability of existing institutions to respond effectively helped shape public support for expanded federal intervention and created the political conditions that enabled the New Deal to transform the structure of relief. When Roosevelt assumed office in 1933, he inherited a fragmented system on the verge of collapse, one that illustrated the limits of decentralized governance during a national economic emergency.

New Deal Emergency Relief and Work Programs

When Franklin D. Roosevelt entered office in March 1933, unemployment had reached levels that local and state governments could no longer manage. His administration responded by launching a series of emergency relief initiatives intended to stabilize households, expand purchasing power, and prevent further economic deterioration. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration became the first major relief agency of the New Deal, distributing federal grants to states to support direct aid. Its records show that millions of households relied on cash assistance or work relief during its first year of operation, a level of support that no prior national institution had attempted.29 The creation of FERA marked the moment when federal responsibility for unemployment shifted from symbolic coordination to material intervention.

One of the most visible early work programs was the Civilian Conservation Corps, which provided employment to young unmarried men in reforestation, soil conservation, and wildfire prevention. Enrollment records demonstrate that the Corps eventually employed more than three hundred thousand men at a time, with camps operating in every state.30 The program offered wages, food, housing, and vocational training, and families benefited directly because most participants sent a required portion of their earnings home. Contemporary evaluations by the Department of Labor emphasized the CCC’s effectiveness in providing immediate employment and supporting regional development through conservation projects that continued to benefit communities long after the Depression.

The Civil Works Administration represented a more intensive experiment in work relief. Created in late 1933, it provided jobs to more than four million workers in a matter of months on construction, repair, and service projects. CWA records show that the rapid expansion of employment helped stabilize purchasing power during the harsh winter of 1933–1934, particularly in urban areas where joblessness had been most severe.31 Although the program lasted only a few months, its scope demonstrated the capacity of the federal government to mobilize vast labor resources when coordinated through federal agencies rather than left to states or municipalities.

The Works Progress Administration, created in 1935, became the largest long term work relief program of the New Deal. It employed workers in construction, education, public health, and the arts, creating infrastructure that reshaped communities across the country.32 Project summaries from the WPA detail the construction of roads, schools, airports, and public buildings, as well as cultural initiatives such as theater productions, oral history projects, and community art programs. Unlike earlier programs, the WPA incorporated workers with varied skills and levels of education, reflecting an understanding that the federal government needed to provide opportunities for both manual and professional labor.

These programs also reshaped political expectations surrounding federal intervention. Relief administrators emphasized that employment, rather than direct cash payments, preserved workers’ dignity and encouraged participation in community life. Reports from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration note that households receiving work relief reported greater stability and fewer long term hardships than those relying purely on direct aid.33 At the same time, debates within the Roosevelt administration revealed tensions between providing immediate relief and promoting structural reforms that would prevent future crises. Some policymakers argued for a permanent system of public employment, while others viewed work relief as a temporary necessity during an extraordinary emergency.

Although these initiatives alleviated immediate suffering, they did not eliminate unemployment entirely. By 1937 the economy showed signs of recovery, but a new downturn that year revealed the continuing vulnerability of households to economic instability.34 Scholars have noted that relief programs succeeded in expanding income, stabilizing communities, and preventing deeper social collapse, yet they remained insufficient to restore full employment. Their limitations underscored the scale of the economic crisis and foreshadowed the additional expenditures that would eventually come with wartime mobilization at the end of the decade.

Institutionalizing Labor Security: The Social Security Act of 1935

The passage of the Social Security Act in 1935 marked a fundamental redefinition of federal responsibility for economic security. Prior to its enactment, the United States had no national unemployment compensation system, and workers faced prolonged joblessness without stable protection from income loss. Congressional hearings leading to the Act record widespread support for establishing a coordinated national program after the failures of local and state relief became undeniable.35 The Committee on Economic Security, created by Roosevelt in 1934, drafted an expansive proposal that linked unemployment insurance to state administration but ensured federal oversight, creating a hybrid model that balanced national coordination with regional autonomy.

Unemployment compensation became one of the cornerstone provisions of the Act. States were required to establish their own unemployment insurance systems, funded through payroll taxes, while the federal government levied a uniform tax on employers and offered credits to states that complied with federal standards.36 This structure encouraged states to participate while maintaining national consistency in design and funding. Early administrative reports show that by 1938 nearly all states had operational unemployment systems that provided temporary income to workers who lost their jobs through no fault of their own. These programs helped stabilize incomes and reduce pressure on local relief agencies that had been overwhelmed earlier in the decade.

The Act also introduced old age benefits that created a permanent system of income support for aging workers. Before 1935 older Americans often depended on family networks, charitable institutions, or limited state pensions that varied widely in coverage and adequacy. The Social Security program established a contributory insurance model funded by payroll taxes, with benefits scheduled to begin in 1940.37 Records from the Social Security Board indicate that millions of workers enrolled during the initial years, a scale of participation that demonstrated the broad appeal of a national retirement system. Although the original program excluded certain categories of workers, including agricultural and domestic laborers, it represented the most far reaching federal commitment to economic security in American history.

Debates surrounding the Act revealed differing visions of economic policy within the Roosevelt administration and Congress. Some policymakers advocated for more expansive relief programs that would include health insurance and universal unemployment coverage.38 Others expressed concern that federal involvement would displace state authority or impose excessive costs on employers. Congressional debates preserved in the Congressional Record show that business groups opposed certain tax provisions, while labor organizations pressed for broader protections. The final legislation reflected political compromise, but it also established mechanisms for future expansion as economic conditions and public expectations evolved.

Implementation of the Act required the creation of new administrative structures at both federal and state levels. The Social Security Board coordinated with state agencies to establish eligibility standards, payment procedures, and recordkeeping practices. Administrative manuals published during the first years of the program reveal the extensive bureaucratic development required to create a functioning national system.39 This institutional framework remained flexible enough to accommodate later amendments, including expansions in coverage and increases in benefit levels during the 1940s and 1950s.

The long term significance of the Social Security Act lay in its recognition that unemployment and old age insecurity were systemic risks that demanded national solutions. The Depression had demonstrated that labor markets could collapse at a scale far beyond the capacity of individuals or communities to manage. By creating permanent systems of unemployment insurance and retirement benefits, the Social Security Act redefined the relationship between workers and the federal government and established a foundation for modern social policy in the United States.40 These developments helped stabilize household incomes during economic fluctuations and provided a model for later social welfare initiatives.

Path to Recovery and the Impact of Rearmament

By the late 1930s the American economy showed signs of improvement, but unemployment remained stubbornly high, revealing the limits of relief and work programs alone. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports from the period document that millions of workers continued to rely on irregular employment or remained outside the labor market altogether.41 Industrial production rose during the early years of the Roosevelt administration, yet the recovery proved vulnerable to shifts in federal spending. The recession of 1937–1938 demonstrated that premature reductions in government expenditures could quickly undermine fragile gains. Economists examining the period argue that the downturn exposed the continued weakness of private investment and the fragility of demand in an economy still scarred by years of contraction.

The persistence of unemployment prompted renewed debate within the Roosevelt administration about the appropriate scale and form of federal intervention. Treasury Department officials favored balanced budgets and sought reductions in relief spending, while others argued for sustained or expanded federal commitments. Correspondence preserved in the papers of the Works Progress Administration reveals disagreements over whether the federal government should maintain long term public employment programs or transition workers back into private industry.42 These debates reflected broader tensions in economic policy as policymakers attempted to balance fiscal restraint with the need to support households that had little prospect of stable employment.

Rearmament in the late 1930s altered this landscape dramatically. European political instability, rising military tensions, and congressional appropriations for defense production generated a surge in demand for industrial output. War Production Board summaries show that federal contracts for aircraft, ships, and armaments began to accelerate well before the United States formally entered the Second World War.43 Factories expanded shifts, reopened previously shuttered facilities, and hired workers at a pace unmatched since the 1920s. The defense buildup initiated a transformation in labor markets, drawing unemployed workers into industries that had been stagnant or declining only a few years earlier.

The transition from peacetime relief to wartime production created immediate effects on employment. Industries such as steel, automobiles, and machine tools experienced dramatic increases in output, and defense contractors recruited workers nationwide. Bureau of Labor Statistics wartime data show that by 1941 unemployment had fallen sharply as military contracts absorbed available labor.44 The geographic distribution of employment also shifted, with significant growth in coastal regions and industrial centers involved in shipbuilding, aviation, and munitions production. Migration patterns changed as workers relocated to areas experiencing rapid expansion, creating new regional labor landscapes.

By the early 1940s the United States had effectively reached full employment. Scholars emphasize that it was the scale of wartime spending, rather than the relief programs of the 1930s, that finally eliminated unemployment.45 The mobilization required financial commitments far exceeding those of any New Deal program and demonstrated the capacity of large scale federal expenditure to reshape labor markets. The contrast between the limited recovery of the mid 1930s and the rapid absorption of labor during the defense buildup underscored the importance of aggregate demand in sustaining employment, a lesson that influenced postwar economic policy and debates surrounding federal responsibility for stabilizing the economy.

Conclusion

The crisis of unemployment during the Great Depression transformed the relationship between American workers and the federal government. The collapse of labor markets exposed the limits of local and state relief and demonstrated that private charity and decentralized governance could not manage nationwide economic failure. Contemporary reports from the early 1930s show that households confronted long term unemployment without the institutional protections that would later become central to American social policy.46 The unprecedented scale of the crisis forced policymakers to reconsider long standing assumptions about the boundaries of public responsibility.

Federal intervention in the form of relief and work programs reshaped expectations of government in American life. New Deal initiatives provided income, employment, and stability to millions of families who otherwise faced prolonged hardship. Administrative records from the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, and the Works Progress Administration reveal the extensive reach of these programs and the immediate impact they had on communities across the country.47 Their success in mitigating suffering demonstrated the importance of coordinated national action, even though they did not restore full employment on their own.

The Social Security Act of 1935 institutionalized the federal role by creating permanent systems of unemployment insurance and retirement benefits that extended beyond the temporary demands of the Depression. Policymakers understood that unemployment was not simply a personal misfortune but a structural risk inherent in modern industrial economies. Legislative debates and administrative reports from the late 1930s show that the Act provided a foundation for future expansions of social policy and stabilized the economic security of millions of workers.48 These developments created a lasting shift in the trajectory of American governance.

Wartime mobilization ultimately achieved what relief programs could not by restoring full employment through large scale federal expenditure. Defense production absorbed available labor, revived stagnant industries, and reshaped migration patterns across the country.49 The contrast between the partial recovery of the mid 1930s and the rapid labor absorption of the early 1940s underscored the power of aggregate demand and reinforced the principle that economic stability required robust public policy. Together these transformations redefined the responsibilities of the federal government, created enduring protections for workers, and reshaped the political and economic landscape of the United States.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” Historical Unemployment Series; David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 86–90; Christina D. Romer, “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 105, no. 3 (1990): 597–624.

- Library of Congress, “Voices from the Dust Bowl,” American Folklife Center; Federal Writers’ Project, Slave Narratives and Life Histories, Library of Congress; Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- United States Congress, Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930; Douglas A. Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot Hawley and the Great Depression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

- Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963).

- Barry Eichengreen, Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

- Civilian Conservation Corps, Annual Report of the Director (1933–1935); Civil Works Administration Records, National Archives.

- Social Security Board, Social Security Act of 1935.

- War Production Board, War Production Board Reports (1942–1945); Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment and Payrolls During World War II,” BLS Historical Archives; Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 303–345.

- Robert Higgs, “Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s,” Journal of Economic History 52, no. 1 (1992): 41–60.

- Stanley Lebergott, Manpower in Economic Growth: The American Record since 1800 (New York: McGraw Hill, 1964); Christina D. Romer, “The Prewar Business Cycle Reconsidered: New Estimates of Gross National Product, 1869–1908,” Journal of Political Economy 97, no. 1 (1989): 1–37.

- President’s Emergency Committee for Employment, Preliminary Reports, National Archives; United States Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States (1930–1935).

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, State Relief Reports, National Archives; James Richardson, Interpreting American History: The New Deal and the Great Depression (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Development of the Monthly Unemployment Series,” BLS Historical Archives.

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Historical Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers,” BLS Historical Series.

- United States Congress, Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930; Douglas A. Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot Hawley and the Great Depression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

- Federal Reserve Board, Annual Report (1931–1933); Barry Eichengreen, Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Statistics (1930–1935).

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.

- Federal Writers’ Project, Life Histories and Interviews, Library of Congress, American Folklife Center.

- United States Children’s Bureau, Annual Reports (1930–1935).

- Farm Security Administration, Photographic Prints Collection, Library of Congress.

- California State Emergency Relief Administration, Reports on Transient Populations (1933–1935).

- New York City Welfare Council, Emergency Relief Reports (1930–1933).

- Daniel Walkowitz, Working with Class: Social Workers and the Politics of Middle Class Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

- Detroit City Council, Proceedings of the Common Council (1930–1932); Cleveland City Council, Journal of Proceedings (1931).

- Charity Organization Society of New York, Annual Reports (1930–1933).

- President’s Emergency Committee for Employment, Preliminary Reports (1930–1931), National Archives.

- National Governors’ Conference, Relief and Public Welfare in the States (1932).

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, First Annual Report of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934).

- Civilian Conservation Corps, Annual Report of the Director (1933–1937).

- Civil Works Administration, Final Statistical Report of the Civil Works Administration (1934), National Archives.

- Works Progress Administration, Report on Progress of the WPA Program (1936–1940), U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, State Relief Reports (1934–1935), National Archives.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment, Hours, and Earnings, 1937–1938,” BLS Historical Series.

- United States Congress, Hearings on the Social Security Bill, House Committee on Ways and Means (1935).

- Committee on Economic Security, Report to the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1935).

- Social Security Board, Annual Report of the Social Security Board (1936–1938).

- Congressional Record, 74th Congress, Debates on H.R. 7260 (1935).

- Social Security Board, Administrative Manual, Unemployment Insurance (1936), National Archives.

- Edwin Amenta, Bold Relief: Institutional Politics and the Origins of Modern American Social Policy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment, Hours, and Earnings, 1930–1940,” BLS Historical Series.

- Works Progress Administration, Correspondence of the Administrator, 1935–1939, National Archives.

- War Production Board, War Production Board Reports (1940–1942), U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment and Payrolls During World War II,” BLS Historical Archives.

- Robert Higgs, “Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s,” Journal of Economic History 52, no. 1 (1992): 41–60; Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- New York City Welfare Council, Emergency Relief Reports (1930–1933).

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, First Annual Report of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (1934); Works Progress Administration, Report on Progress of the WPA Program (1936–1940).

- United States Congress, Hearings on the Social Security Bill, House Committee on Ways and Means (1935).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment and Payrolls During World War II,” BLS Historical Archives; War Production Board, War Production Board Reports (1940–1942).

Bibliography

- Amenta, Edwin. Bold Relief: Institutional Politics and the Origins of Modern American Social Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Development of the Monthly Unemployment Series.” BLS Historical Archives.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment and Payrolls During World War II.” BLS Historical Archives.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings, 1930–1940.” BLS Historical Series.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings, 1937–1938.” BLS Historical Series.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Historical Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.” BLS Historical Series.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.” Historical Unemployment Series.

- California State Emergency Relief Administration. Reports on Transient Populations. 1933–1935.

- Charity Organization Society of New York. Annual Reports. 1930–1933.

- Children’s Bureau (United States). Annual Reports. 1930–1935.

- Civilian Conservation Corps. Annual Report of the Director. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1933–1937.

- Civil Works Administration. Final Statistical Report of the Civil Works Administration. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934.

- Cleveland City Council. Journal of Proceedings. 1931.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Committee on Economic Security. Report to the President. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1935.

- Congressional Record. 74th Congress. Debates on H.R. 7260. 1935.

- Detroit City Council. Proceedings of the Common Council. 1930–1932.

- Eichengreen, Barry. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration. First Annual Report of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration. State Relief Reports. 1934–1935. National Archives.

- Federal Reserve Board. Annual Report. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board, 1931–1933.

- Federal Writers’ Project. Life Histories and Interviews. Library of Congress, American Folklife Center.

- Federal Writers’ Project. Slave Narratives and Life Histories. Library of Congress.

- Farm Security Administration. Photographic Prints Collection. Library of Congress.

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

- Higgs, Robert. “Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s.” Journal of Economic History 52, no. 1 (1992): 41–60.

- Irwin, Douglas A. Peddling Protectionism: Smoot Hawley and the Great Depression. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Lebergott, Stanley. Manpower in Economic Growth: The American Record since 1800. New York: McGraw Hill, 1964.

- Library of Congress. “Voices from the Dust Bowl.” American Folklife Center.

- National Governors’ Conference. Relief and Public Welfare in the States. Washington, DC: National Governors’ Conference, 1932.

- New York City Welfare Council. Emergency Relief Reports. 1930–1933.

- President’s Emergency Committee for Employment. Preliminary Reports. 1930–1931. National Archives.

- Richardson, James. Interpreting American History: The New Deal and the Great Depression. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

- Romer, Christina D. “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 105, no. 3 (1990): 597–624.

- —- “The Prewar Business Cycle Reconsidered: New Estimates of Gross National Product, 1869–1908.” Journal of Political Economy 97, no. 1 (1989): 1–37.

- Social Security Board. Administrative Manual, Unemployment Insurance. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936.

- Social Security Board. Annual Report of the Social Security Board. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936–1938.

- United States Congress. Hearings on the Social Security Bill. House Committee on Ways and Means. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1935.

- United States Congress. Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Statistics. 1930–1935.

- United States Department of Commerce. Statistical Abstract of the United States. 1930–1935.

- Walkowitz, Daniel. Working with Class: Social Workers and the Politics of Middle Class Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- War Production Board. War Production Board Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1940–1942.

- Works Progress Administration. Correspondence of the Administrator, 1935–1939. National Archives.

- Works Progress Administration. Report on Progress of the WPA Program. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936–1940.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.