The incarceration of Japanese Americans during the Second World War demonstrates how national security concerns can be reframed through racial ideology.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Japanese Americans and the Making of an Internal Enemy

The attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 produced a political climate in which Japanese Americans were rapidly transformed from neighbors and citizens into objects of suspicion. Public anxiety and longstanding racial bias merged into a narrative that cast people of Japanese ancestry as potential threats to national security. Although no evidence indicated widespread disloyalty, military and civilian officials framed the West Coast as a zone in which ordinary constitutional protections could be suspended. This shift laid the groundwork for policies that targeted more than one hundred thousand individuals, two thirds of whom were American citizens, for forced removal and incarceration.1

The mechanism for this transformation emerged through presidential authority. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, granting the War Department power to designate military areas and exclude persons deemed a danger. The order contained no reference to Japanese Americans, yet it created an administrative space in which military commanders exercised broad discretion with minimal oversight. The Western Defense Command soon issued civilian exclusion orders that applied almost exclusively to individuals of Japanese ancestry.2 Under this framework, mass action replaced individualized assessments, and citizenship no longer provided protection from military power.

The consequences of these policies appeared immediately in the daily lives of Japanese American communities. Families received notices instructing them to dispose of property, close businesses, and prepare for forced removal within days. Many struggled to sell homes, farms, and equipment under intense time pressure, often accepting prices far below market value.3 Government agencies offered no meaningful assistance or compensation. The swift nature of removal revealed how little consideration had been given to the human and economic impact of these actions. It also demonstrated the extent to which racial assumptions shaped decision making, since no comparable system targeted other groups on the West Coast.

Military and civilian agencies organized the next phase of confinement through a network of temporary assembly centers housed in converted racetracks and fairgrounds. Families were held in overcrowded stalls and makeshift barracks surrounded by guards and barbed wire.4 These conditions reflected the government’s belief that Japanese Americans required containment but did not warrant the protections ordinarily associated with detention. Assembly centers served as holding sites until larger, long term relocation centers could be completed in remote areas of the interior. The system functioned as a chain of displacement, moving people from their homes into temporary sites and ultimately into desert or swamp environments where surveillance and control were constant.

The forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans revealed how racial ideology and wartime fear could reshape the boundaries of constitutional rights. The government justified its actions through claims of military necessity, yet subsequent investigations found no evidence of disloyal conduct that would have warranted mass exclusion.5 The creation of assembly and relocation centers reflected a political decision rather than an unavoidable wartime response. This introduction sets the stage for examining how administrative authority, racialized national security, and the erosion of due process combined to produce one of the most sweeping violations of civil liberties in United States history.

Executive Order 9066 and the Legal Foundations of Incarceration

Executive Order 9066 created the legal structure that allowed military officials to transform racial suspicion into state policy. The order itself used neutral language about “military areas,” but its practical effect was to grant the War Department sweeping authority to exclude any person without requiring evidence of disloyalty. Within days, the Western Defense Command issued regulations that defined the entire West Coast as a restricted zone.6 These directives gave military officers the ability to circumvent the usual mechanisms of due process. Lawyers within the War Department justified the authority by emphasizing the unpredictable nature of modern warfare, arguing that exclusion could be preventive rather than punitive. Yet the broad scope of the order ensured that the policy targeted entire communities rather than individuals whose conduct had raised any specific concern.

The legal instruments that followed reinforced this system of extrajudicial action. Public Law 503, passed by Congress in March 1942, made it a federal crime to violate any military order issued under EO 9066.7 This law did not define standards for exclusion or establish procedures for appeal. Instead, it provided criminal penalties that allowed the government to prosecute Japanese Americans who violated curfew rules, travel restrictions, or exclusion notices. The existence of such penalties heightened the pressure to comply with removal orders even when individuals believed their rights were being violated. The courts accepted the basic framework of the legislation, giving the government a legal veneer for policies that fundamentally altered the relationship between citizens and the state.

Military officials defended exclusion as a temporary measure motivated by wartime necessity, but internal records show that the policy rested largely on racial assumptions. Reports from the Western Defense Command cited concerns that Japanese Americans were “unassimilable” because of cultural and ancestral ties, rather than because of evidence of espionage or sabotage.8 The Federal Bureau of Investigation had already investigated and detained individuals considered actual security risks, and its leadership reported that further mass action was unnecessary. Nevertheless, military authorities proceeded with broad exclusion, arguing that it was impossible to conduct individual assessments on the required scale. The claim of administrative impossibility became a justification for collective punishment.

Legal scholars and later federal commissions identified the fundamental flaw in the government’s approach. The structure created by EO 9066 eroded constitutional protections by placing decisions about liberty entirely within the hands of military commanders. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) concluded in 1982 that the policy had been shaped by racial prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership rather than by any genuine military need.9 Despite these findings, the wartime legal framework permitted the incarceration of tens of thousands of people who had no mechanism to challenge the deprivation of their homes, property, and freedom. The combination of executive authority, legislative support, and military discretion produced a system of confinement that operated outside the ordinary boundaries of American law.

Removal under Pressure: Property Loss, Coercion, and Forced Displacement

The removal process unfolded through a series of military orders that required Japanese Americans to abandon their daily lives with almost no preparation. Notices posted in towns and cities along the West Coast instructed families to bring only what they could carry and to assemble at designated points within days. These directives made no distinction between citizens and immigrants. They treated entire communities as potential threats whose continued presence was incompatible with wartime security. The compressed timeline left families struggling to decide what items to bring, what to store, and what to relinquish. Many people later recalled the sense of disbelief that ordinary life could be dismantled so rapidly through a single exclusion order.10

The economic impact of forced removal was immediate and severe. Farmers were compelled to sell crops, land, and equipment at distressed prices because potential buyers knew they had no bargaining power. Urban residents faced similar pressures, often selling homes, stores, and personal belongings for a fraction of their value. The CWRIC documented widespread property losses, noting that families “had no opportunity to protect their assets or obtain fair compensation.”11 Many placed belongings in storage facilities that were later vandalized or repossessed. Even when people attempted to leave property with trusted neighbors, wartime pressures and discriminatory attitudes often resulted in additional losses. The government provided no meaningful mechanism for safeguarding property during removal.

Transportation to assembly centers deepened the sense of coercion. Military police escorted families to pick up points where buses or trains transported them to temporary holding sites. These assembly centers were hurriedly constructed, frequently on fairgrounds or racetracks, and offered little privacy or comfort.12 Families were assigned to makeshift living quarters that reflected the government’s failure to plan for basic needs. Individuals reported that livestock stalls at centers like Santa Anita still carried the smell of horses, and sanitary facilities were inadequate for the number of residents. The government described these sites as temporary waystations, yet the conditions set the tone for the larger confinement system that followed.

The removal process also revealed the extent to which Japanese Americans were denied meaningful choice. Federal officials described the early stages as “voluntary evacuation,” but archival evidence shows that those who attempted to relocate independently encountered hostility, restrictive local ordinances, and pressure from authorities that made such movement nearly impossible.13 In practice, any attempt to avoid incarceration risked arrest under Public Law 503. The language of voluntariness served primarily to mask the coercive nature of the policy. Residents understood that compliance was required and that refusal would bring criminal penalties. The pretense of choice concealed the reality of forced displacement.

These pressures created emotional and psychological burdens that were inseparable from the physical uprooting. Many families carried the knowledge that their forced departure was driven by racial animosity rather than personal conduct. Diaries and oral histories preserved in the Densho Digital Archive describe the pain of leaving behind pets, heirlooms, gardens, and community networks.14 Elderly residents struggled with the rapid transition, and children sensed the fear that surrounded them as soldiers and police directed the evacuation. The government’s insistence on treating Japanese Americans as a collective risk eroded trust in public institutions and left a legacy of trauma that shaped later generations.

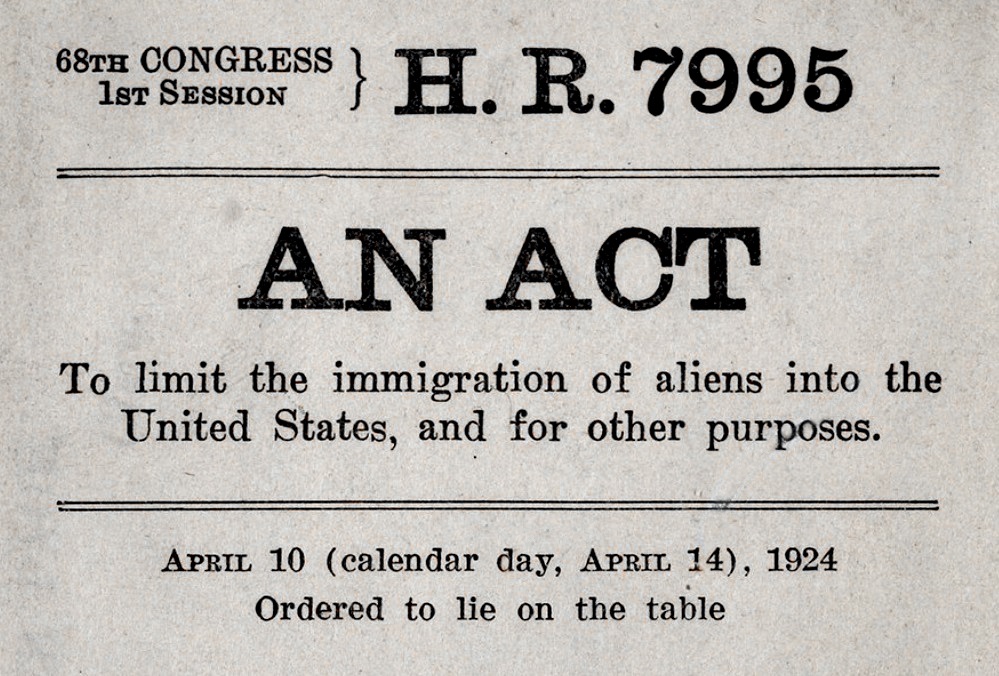

Historians analyzing this period emphasize that removal was not merely a logistical undertaking but a form of racialized state violence. The policy must be understood within a longer history of exclusionary immigration laws and anti-Asian sentiment in the United States.15 The forced sale of property, breakdown of communities, and loss of autonomy were not incidental outcomes but predictable consequences of a system built on the assumption that ancestry could determine loyalty. By examining these processes, it becomes clear that the removal of Japanese Americans was driven by structural racism amplified by wartime fear. The forced displacement created conditions from which families would struggle to recover long after the war had ended.

Assembly Centers: Temporary Confinement in Converted Civilian Spaces

Assembly centers were the first physical manifestation of the government’s confinement system and revealed the improvisational nature of wartime exclusion. Once removal orders were issued, Japanese Americans were transported to temporary holding sites located primarily at racetracks, county fairgrounds, and exhibition spaces. These facilities had been chosen for their large capacity rather than their suitability for human habitation. The War Relocation Authority later acknowledged that the speed of the removal process left little time for preparation. Families arrived to find converted livestock stalls, hastily built barracks, and open communal latrines that provided minimal privacy.16 The abrupt transformation of public recreational spaces into detention sites underscored the government’s willingness to sacrifice civil norms in the name of security.

Conditions inside assembly centers varied, but overcrowding and inadequate sanitation were common. Large rooms were divided by thin partitions that did not block sound, and the rapid influx of thousands of residents strained water supplies and medical services. Infectious diseases spread easily in the crowded quarters. At the Santa Anita Assembly Center, built around a functioning racetrack, thousands of people lived in converted horse stalls, many of which retained dust, odors, and structural limitations associated with their original purpose.17 Complaints documented by WRA officials described insufficient bathing facilities, insect infestations, and food shortages that reflected the scale of the logistical challenge. These complaints provided an early indication of the structural deficiencies that would later appear in the relocation centers.

Despite these conditions, the government attempted to frame assembly centers as orderly, controlled environments. Reports produced by the WRA described the facilities as temporary communities in which residents could contribute to camp life through cleaning crews, mess hall duties, or volunteer organizations. Yet oral histories and personal diaries consistently reveal a sense of disorientation and loss.18 The contradiction between official portrayals and lived experiences reflects the broader disjunction in wartime policy. Authorities emphasized the temporary nature of the sites, while residents struggled to adapt to the reality of confinement under guard. The lack of clarity about the duration or purpose of the stay contributed to a pervasive sense of uncertainty.

Daily life in the assembly centers also highlighted the racial logic that underpinned the entire system. Armed military police monitored perimeters, and guard towers reinforced the perception that Japanese Americans were being held as prisoners rather than as civilians under administrative care. Families became subject to curfews, regulated meal schedules, and restrictions on movement within the compound.19 The presence of soldiers patrolling fences created an atmosphere in which normal patterns of autonomy were replaced by formalized surveillance. Residents who sought space for privacy or moments of psychological relief found their options limited. Assembly centers thus became transitional spaces in which the government normalized the treatment of Japanese Americans as people whose freedom could be curtailed without due process.

Although the assembly centers were intended as temporary measures, they played a central role in shaping the experience of incarceration. These sites introduced families to the administrative routines that would govern their lives for years. Medical examinations, property inspections, and camp identification procedures foreshadowed the deeper intrusions of the relocation centers.20 The combination of institutional disorder and growing regimentation revealed a system that had been built hastily but was capable of long term control. By the time residents were transferred to permanent camps, they had already endured the first stage of a confinement process that challenged the fundamental meaning of citizenship in the United States.

Relocation Centers: Long-Term Incarceration and the Structure of Camp Life

Relocation centers formed the core of the long-term incarceration system that held Japanese Americans for up to four years. Administered by the War Relocation Authority, these camps were built in remote regions of the interior, including deserts, swamps, and high plains that created harsh living conditions. Families who had already endured the assembly centers found themselves transported hundreds of miles inland by guarded trains. Upon arrival, rows of tar paper barracks surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers revealed a setting that bore more resemblance to prisons than to the “communities” described in government publications.21 The placement of the camps in isolated terrain ensured limited contact with the outside world and reinforced the idea that Japanese Americans required segregation from the broader population.

Daily life within the relocation centers revolved around regimentation and surveillance. The WRA established administrative structures that regulated work assignments, education, healthcare, and food distribution. Residents received identification numbers that replaced ordinary civic documentation.22 Armed military police patrolled the perimeters, and camp administrators enforced strict rules governing curfews and movement. Barracks lacked insulation, forcing families to endure extreme temperatures. Dust storms, inadequate heating, and limited medical supplies created chronic discomfort. Although some attempts were made to provide schooling and employment, the underlying environment constrained autonomy and reinforced a sense of confinement. The combination of routine and restriction shaped a daily reality in which personal agency was sharply curtailed.

The internal organization of the camps depended heavily on the labor of the incarcerated themselves. Residents staffed schools, hospitals, mess halls, and maintenance crews under the direction of WRA officials. Camp newspapers, produced by residents, documented both community resilience and ongoing frustration.23 These sources reveal efforts to sustain cultural life, from sports teams to religious services. Yet they also record grievances about food quality, unpaid or low paid labor, and administrative decisions that ignored community voices. The reliance on resident labor served a practical function for the government, reducing operational costs, but it also reinforced the unequal power structure within the camps. Participation in camp life did not mitigate the fact that residents remained confined without charge.

Relationships within the camps were affected by the uncertainty of the incarceration’s duration and by tensions created by government policies. Those who cooperated with WRA initiatives often clashed with individuals who resisted perceived injustice. Scholars have noted that the loyalty questionnaire of 1943 intensified these divisions by forcing residents to answer ambiguous questions about military service and allegiance.24 Responses could result in family separations or transfers to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, which became a heavily policed site for individuals labeled problematic. The questionnaire’s impact illustrated how the government’s administrative practices intruded upon intimate aspects of identity and belonging, creating divisions that lingered long after the war ended.

Camp conditions also demonstrated how incarceration reshaped legal and civic identities. Residents who attempted to challenge their confinement encountered bureaucratic obstacles and legal uncertainty. Despite being American citizens, they remained under military jurisdiction and lacked access to courts that could review the legality of their detention.25 The structure of the relocation centers thus reflected a profound deviation from constitutional principles. It placed an entire population under a system that blended civilian administration with military oversight. By the time families left the camps in 1945, many had lost homes, savings, and years of their lives within an environment created by wartime prejudice rather than individualized evidence. The relocation centers stand as a reminder of how state power can redefine the boundaries of freedom when racialized national security concerns go unchallenged.

Citizenship, Race, and the Suspension of Due Process

The incarceration of Japanese Americans represented a profound break with constitutional norms and highlighted the degree to which race shaped interpretations of national security. Although the majority of those removed from the West Coast were American citizens, their legal status did not protect them once EO 9066 placed decisions about exclusion in the hands of military commanders. The lack of individualized assessment meant that citizenship was effectively overridden by ancestry.26 Government memoranda from early 1942 reveal that officials framed exclusion as a preventive measure rather than a punitive one, but this distinction mattered little to the people who were ordered to leave their homes under military guard. The suspension of due process was justified through a broad understanding of “military necessity” that treated racial identity as sufficient grounds for action.

The courts reinforced this erosion of constitutional protections. In Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), the Supreme Court upheld the curfew imposed on Japanese Americans, accepting the government’s argument that wartime conditions justified broad racial restrictions.27 A year later, the Court reached similar conclusions in Korematsu v. United States, ruling that exclusion from the West Coast was constitutional despite the absence of evidence indicating individual disloyalty. These decisions reflected deference to executive and military authority, even when the policies in question targeted a racially defined group. The Court’s reasoning ignored the underlying context of prejudice documented within military and civilian agencies, thereby legitimizing the legal framework that supported mass incarceration.

Although the Court endorsed exclusion, it reached a different conclusion regarding detention in Ex parte Endo (1944). The justices ruled that the government could not detain loyal American citizens who had been found to pose no threat.28 This decision did not directly challenge the exclusion policy, but it undermined the rationale for holding Japanese Americans in relocation centers once the War Relocation Authority had determined that many residents were loyal. The ruling pushed federal officials to begin the process of closing the camps, although the decision came after nearly three years of incarceration. The contradiction between the Korematsu and Endo decisions revealed the instability of the government’s legal justification and exposed the tension between wartime policies and constitutional principles.

Investigations conducted decades later confirmed what many Japanese Americans had argued from the beginning. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded in its 1982 report that the incarceration had been shaped by racial prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership rather than by proven military necessity.29 The Commission found no evidence of espionage or sabotage by Japanese Americans on the West Coast and criticized the government for suppressing intelligence reports that contradicted its public claims. These findings reinforced the historical view that the policy rested on unfounded assumptions and that the suspension of due process had produced widespread injustice. The report served as an official acknowledgment of the constitutional violations committed during the war.

The denial of legal recourse was further compounded by the government’s failure to provide mechanisms for compensating damaged or lost property. Japanese Americans were forced to navigate a patchwork of inadequate programs, such as the Claims Act of 1948, which seldom restored the value of homes, farms, or businesses lost during removal.30 The absence of timely compensation highlighted the depth of the government’s disregard for the economic and legal rights of its own citizens. Families who had been uprooted under the banner of national security returned to find their livelihoods shattered and their communities dispersed. The slow and limited nature of postwar assistance reflected the lingering effects of racialized assumptions that had justified the incarceration.

The suspension of due process during the incarceration of Japanese Americans illustrates how wartime fear can distort legal protections when racial ideology becomes intertwined with national security. Scholars have emphasized that the constitutional violations of the early 1940s were not inevitable responses to military conditions but choices shaped by prejudice and political calculation.31 The experience of Japanese Americans demonstrates how easily rights can be curtailed when the government constructs entire communities as potential threats. By examining the legal and racial dynamics that enabled incarceration, this section illuminates the broader implications of policies that prioritize perceived security over constitutional safeguards.

Resistance, Compliance, and Community Responses Within the Camps

Japanese Americans responded to incarceration through a range of strategies shaped by age, generation, political outlook, and camp conditions. Many residents attempted to maintain daily routines and preserve family stability amid forced confinement. Community leaders organized schools, sports programs, religious services, and cultural events that helped maintain cohesion in an environment designed to suppress agency.32

These efforts reflected a determination to sustain dignity under oppressive circumstances, even as families struggled to navigate the psychological burden of confinement. Maintaining a semblance of normalcy was itself a form of resilience that countered the narrative of passivity often associated with incarceration.

Legal challenges emerged early in the incarceration process, led by individuals who rejected the government’s claim that ancestry could determine loyalty. Gordon Hirabayashi, Minoru Yasui, and Fred Korematsu each defied curfew or exclusion orders to test the constitutionality of the government’s actions. Their cases reached the Supreme Court in 1943 and 1944, generating national attention despite the unfavorable rulings.33 These challenges forced the government to defend its policies in public forums and revealed weaknesses in the logic behind mass exclusion. Although the Court accepted the government’s arguments during the war, the legal record produced by these cases later provided critical evidence of constitutional misconduct.

Inside the relocation centers, protest took collective as well as individual forms. Strikes at camps such as Manzanar and Poston were sparked by disputes over working conditions, rationing, and the treatment of detainees accused of disloyalty.34 These incidents reflected frustration with administrative policies that demanded cooperation while offering limited transparency or accountability. Camp administrators often responded by tightening security measures, imposing curfews, or segregating individuals labeled as troublemakers. The strikes demonstrated that communities were not passive recipients of government policy but active participants in shaping the internal dynamics of the camps, even when those efforts carried significant risk.

One of the most significant points of tension arose with the 1943 loyalty questionnaire, which forced residents to declare willingness to serve in the U.S. military and to forswear any allegiance to the Japanese emperor. For many of those incarcerated, the questions were deeply confusing, especially for U.S.-born citizens who felt that their loyalty had never been in doubt. Others feared that answering affirmatively might separate them from family members who answered differently.35 Those who responded “no” to both controversial questions, often labeled “No-No,” were transferred to Tule Lake after it became the system’s segregation center. Conditions there included heightened surveillance, increased militarization, and deeper divisions between residents. The questionnaire revealed the extent to which policy makers used administrative tools to shape community behavior and measure conformity to wartime expectations.

Resistance also emerged through draft protests, most notably at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Members of the Fair Play Committee refused induction into the U.S. military unless their rights as citizens were restored.36 Their stance challenged the contradiction of being asked to fight for freedoms they were denied at home. Government officials prosecuted many resisters, and public debate over their actions revealed deep rifts both within Japanese American communities and in broader American society. After the war, however, many of these resisters were recognized for highlighting the fundamental injustice of the incarceration. Their actions demonstrate how Japanese Americans confronted the moral complexities of wartime citizenship, even as state power constrained their options.

Aftermath: Redress, Memory, and the Legacy of Wartime Incarceration

The end of the war did not immediately repair the damage caused by the incarceration. Most Japanese Americans left the camps between 1944 and 1945 to find that their homes, farms, and businesses had been sold, vandalized, or seized during their absence. Many returned to cities where anti Japanese sentiment lingered, and where housing discrimination restricted settlement options.37 Families who had once lived in stable communities were often forced into temporary hostels, churches, or converted military barracks while they struggled to rebuild their lives. The economic harm documented by federal commissions shows that recovery was uneven and that many never regained the financial security they had lost.

Government programs offered limited assistance. The WRA provided small resettlement stipends, but these funds could not compensate for years of lost income or the forced liquidation of property.38 In 1948, Congress passed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, which allowed individuals to file claims for losses. Yet the program required complicated documentation, and approved payments rarely matched the actual value of property forfeited under duress. The CWRIC later concluded that the law failed to deliver meaningful restitution and that it reflected an incomplete understanding of the consequences of mass removal.39 These shortcomings burdened the community for decades.

Public memory of the incarceration shifted gradually as survivors began sharing their experiences more widely. Oral histories, community archives, and cultural activism played essential roles in reshaping national understanding of the wartime policies. Organizations formed by former incarcerated persons and their descendants pushed for official acknowledgment and compensation. Their efforts converged in the establishment of the CWRIC in 1980, which conducted interviews, reviewed government records, and published its findings in Personal Justice Denied.40 The report concluded that the incarceration had been motivated by racial prejudice, war hysteria, and political failure rather than by proven military need. This federal acknowledgment marked a turning point in the broader narrative.

These findings ultimately contributed to the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which issued a formal apology on behalf of the United States and authorized monetary redress for surviving detainees. The law represented a significant, though incomplete, effort to confront the injustices of wartime policy. It also signaled a broader public willingness to interrogate the relationship between citizenship, security, and civil rights. Yet the legacies of incarceration extended beyond financial compensation. Communities continued to grapple with generational trauma, disrupted family histories, and a lingering awareness of how tenuous constitutional protections can become during national crises. The aftermath of incarceration therefore occupies a central place in Japanese American memory and remains a crucial part of the larger history of civil liberties in the United States.41

Conclusion: State Power, Racialized National Security, and the Boundaries of Citizenship

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during the Second World War demonstrates how national security concerns can be reframed through racial ideology when institutions fail to maintain constitutional limits. Policies that targeted a population defined by ancestry rather than conduct reflected a deeper history of exclusion that predated Pearl Harbor. Executive Order 9066 provided military authorities with a legal foundation that circumvented judicial oversight, and this framework allowed decisions based on generalized suspicion to replace individualized evaluation.42 As a result, citizenship ceased to function as a guarantee of rights. The government’s treatment of Japanese Americans reveals how easily constitutional protections can erode when political leaders interpret racial identity as evidence of potential disloyalty.

The long duration of incarceration, combined with the structure of the camps, exposed the extent to which administrative authority can transform ordinary life into a system of control. The War Relocation Authority’s regulation of employment, education, and community governance created an environment in which surveillance and loss of autonomy shaped daily existence.43 Residents adapted through cultural, social, and political responses, but their capacity to do so remained constrained by the fundamental fact of confinement. The physical separation of Japanese Americans from the rest of the population depended on both federal policy and local cooperation, showing how multiple layers of government contributed to maintaining the incarceration system.

Legal challenges brought during the war and the investigations that followed illustrate the difficulty of contesting state action during periods of crisis. While the Supreme Court upheld exclusion and curfew policies, the decision in Ex parte Endo and later findings by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians revealed the underlying contradictions in the government’s rationale.44 The Commission’s conclusion that incarceration resulted from racial prejudice, war hysteria, and political failure shifted the national understanding of the policy’s origins. By tracing the gaps between wartime rhetoric and historical evidence, scholars and federal investigators helped establish a record that exposed the constitutional violations at the heart of the policy.

The legacy of incarceration continues to shape discussions of civil liberties and national security. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 offered redress, but it also underscored the importance of institutional accountability in preventing future abuses. The experience of Japanese Americans demonstrates that protecting individual rights requires more than legal guarantees. It depends on the willingness of political and legal institutions to resist pressures that encourage the use of race as a measure of loyalty.45 By examining how wartime policies evolved and how communities responded, this history provides a framework for understanding the consequences of racialized security practices and affirms the necessity of vigilance in defending constitutional principles.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Roger Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 1–6.

- Executive Order 9066, February 19, 1942, National Archives; Western Defense Command, Civilian Exclusion Orders, 1942.

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), Personal Justice Denied (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1982), 133–142.

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946), 30–39; Densho Digital Archive, assembly center photographs and testimonies.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, xv–xvi.

- Executive Order 9066.

- Public Law 503, March 21, 1942, 56 Stat. 173.

- Western Defense Command, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1943), 7–12.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 3–18.

- Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial, 30–38.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 133–142.

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation, 30–39; Densho Digital Archive, assembly center records.

- Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 98–103.

- Densho Digital Archive, oral histories and diaries of Japanese American incarcerees, various collections.

- Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 245–252.

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human, 30–39.

- Densho Digital Archive, Santa Anita Assembly Center photographs and testimonies.

- Densho Digital Archive, personal diaries and oral histories of Japanese American incarcerees, various collections.

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation, 35–38.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 143–150.

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation, 40–54.

- National Archives, War Relocation Authority records, camp administrative files.

- Densho Digital Archive, camp newspapers and resident-produced documents, various collections.

- Robinson, By Order of the President, 190–204.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 151–162.

- Executive Order 9066; Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial, 15–22.

- Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943).

- Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 3–18.

- United States Congress, Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, 62 Stat. 1231; CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 303–319.

- Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 257–276; Eric Yamamoto, Interracial Justice (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 42–55.

- Densho Digital Archive, camp newspapers, cultural programs, and oral histories, various collections.

- Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943); Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944); Yasui v. United States, 320 U.S. 115 (1943).

- National Archives, War Relocation Authority records, reports on disturbances at Manzanar and Poston, 1942–1943.

- Robinson, By Order of the President, 190–204.

- Eric L. Muller, Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 45–72.

- Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial, 104–113.

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation, 100–108.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 303–319.

- Ibid., 1–25.

- Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100–383; Eric Yamamoto, Interracial Justice (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 42–55.

- Executive Order 9066; Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

- War Relocation Authority, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation, 40–54.

- CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied, 1–25; Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

- Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100–383; Eric Yamamoto, Interracial Justice, 42–55.

Bibliography

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). Personal Justice Denied. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1982.

- Daniels, Roger. Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

- Densho Digital Archive. Oral histories, diaries, camp newspapers, photographs, and resident–produced documents. Various collections.

- Executive Order 9066. February 19, 1942. National Archives.

- Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

- Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015.

- Muller, Eric L. Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- National Archives. War Relocation Authority administrative files and camp disturbance reports. Various collections.

- Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- United States Congress. Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948. 62 Stat. 1231.

- War Relocation Authority. WRA: A Story of Human Conservation. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946.

- Western Defense Command. Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1943.

- Ex parte Endo. 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

- Hirabayashi v. United States. 320 U.S. 81 (1943).

- Korematsu v. United States. 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

- Yasui v. United States. 320 U.S. 115 (1943).

- Yamamoto, Eric. Interracial Justice. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.