The combination of empirical observation, civic intervention, and evolving environmental theory created a legacy that shaped future approaches to urban health.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Water, Urban Growth, and the Problem of Contamination

The growth of medieval towns placed unprecedented pressure on local water systems, and the strain revealed significant vulnerabilities in the ways communities obtained, managed, and protected their supplies. Rivers, wells, and conduit networks formed the core of urban water access, yet these sources frequently lay in close proximity to waste disposal sites, industrial zones, and densely crowded neighborhoods.1 As populations increased during the high medieval period, municipal authorities confronted rising concerns about polluted waterways and the illnesses that accompanied them. These conditions created the foundation for some of the earliest attempts at urban sanitary regulation in European history.

Medieval urban waterways served many purposes, which magnified the risk of contamination. People drew water for cooking and drinking from the same rivers that received waste from households and trades.2 Archaeological and civic records reveal that industries such as tanning and butchering often operated along riverbanks where disposal was convenient. The competing demands of domestic life and craft production placed heavy burdens on water quality and made management difficult. The tension between everyday use and the dangers of pollution became increasingly visible as towns expanded and more people relied on shared sources.

Medical and technical writers of the Middle Ages attempted to evaluate water quality through empirical observation. Scholars such as those writing within the Hippocratic and Galenic traditions adapted classical criteria for distinguishing healthy from unhealthy waters.3 These assessments relied on characteristics such as clarity, odor, taste, and movement. Although medieval thinkers lacked microbial understanding, their writings show considerable attention to environmental conditions and the behavior of water in natural and urban settings. These early forms of environmental analysis did not yet shape policy directly, but they introduced principles that would influence later interpretations of disease.

Municipal officials responded to the growing problem of contamination by issuing ordinances aimed at protecting water sources. Records from cities such as London, Paris, and Venice include prohibitions on dumping waste into rivers, restrictions on the placement of latrines, and regulations intended to shield public conduits from corruption.4 These measures varied in scope and enforcement, yet they demonstrate that civic leaders recognized the relationship between polluted water and public welfare. Their interventions emerged within a complex social environment in which economic necessity, urban growth, and limited technological capacity constrained the effectiveness of reform.

The challenges posed by contaminated water and the diseases associated with urban environments contributed to the wider acceptance of miasma theory. Medieval authorities linked foul smells and decomposing matter to illness, and their observations reinforced the belief that unhealthy air arising from polluted sites posed direct threats to human health.5 While this theory lacked the precision of modern epidemiology, it encouraged the development of public sanitation measures that targeted the environmental conditions believed to foster disease. These actions formed an early stage in the evolution of public health thought, shaped by the intersection of empirical observation, municipal governance, and the lived experience of crowded medieval cities.

Water Sources and Everyday Use in Medieval Towns

Rivers and shallow wells formed the primary water supply for many medieval towns, and their accessibility made them central to daily routines. Households collected water directly from riverbanks or communal wells, using these sources for drinking, cooking, washing, and brewing.6 In towns without extensive conduit systems, these surface supplies remained indispensable despite risks of contamination. Archaeological work and civic records across England, France, and Italy reveal the degree to which these sources were embedded in the physical and social structure of medieval settlements. Their location near densely inhabited areas contributed to both convenience and vulnerability.

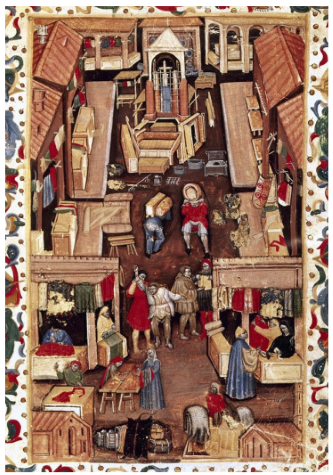

Urban waterways supported far more than domestic tasks. They also powered mills, cooled brewing vats, cleaned raw materials, and received the run off from numerous trades.7 Tanners, butchers, and fullers relied on nearby rivers for processes that produced significant waste. These industries often occupied riverfront zones because accessibility reduced labor and transport costs. The convergence of craft production and household water collection intensified the strain on local ecosystems. Town governments attempted to balance commercial utility with public need, yet economic pressures frequently outweighed concerns about cleanliness.

Water use also varied according to the technological infrastructure available. Larger cities such as London, Paris, and Rome developed conduit systems that carried water from springs or upland sources to central cisterns and fountains.8 These systems provided cleaner water to residents within their distribution radius, though most urban inhabitants still depended on rivers and wells for routine tasks. Conduits offered partial relief from the burden placed on local waterways, but their effectiveness was uneven. Maintenance issues, seasonal shortages, and disputes over access limited their capacity to replace direct collection from open sources.

The quality of river water fluctuated throughout the year. Seasonal changes in rainfall, flooding, and temperature affected sediment levels and flow rates, altering clarity and taste. Medieval observers noted that water from fast moving channels often appeared cleaner and more suitable for consumption, while stagnant zones near wharves and industrial quarters acquired foul odors and discoloration.9 These sensory evaluations guided household decisions about which sources to rely upon, although necessity often forced people to draw from polluted areas regardless of observable conditions. The inconsistency of supply heightened the risks associated with everyday water use.

In rural hinterlands, wells and springs provided more predictable access to water, yet these sources were not immune to contamination. Proximity to cesspits, animal pens, and agricultural runoff threatened groundwater quality. Urban expansion frequently incorporated former rural zones without relocating waste infrastructure, a pattern that brought older wells into close contact with new wastes.10 Civic officials occasionally issued regulations to protect wells from encroachment, but enforcement was uneven. These tensions reveal the complexity of managing water in environments where built structures and natural systems intertwined.

The dependence on shared, unprotected water sources created conditions in which contamination was difficult to avoid. The close integration of domestic life, craft production, and transportation networks meant that rivers and wells carried multiple burdens.11 Towns continued to rely on these sources because alternative systems were expensive and slow to develop. The strain on urban water supplies thus reflected the broader challenges of medieval urbanization, where rapid population growth outpaced the capacity of civic authorities to regulate and maintain essential resources.

Public Latrines, Waste Disposal, and the Burden on Urban Waterways

Public latrines were a common feature of medieval towns, and many were constructed directly over rivers or drainage channels to simplify removal of waste. Civic records from major centers describe latrines positioned above watercourses so that tides or river flow would carry away the contents.12 Although convenient in design, this system created persistent health risks. Human waste entered the same waterways used for washing, brewing, and in some cases drinking. Latrines connected to rivers became chronic sources of pollution, especially in densely settled districts where disposal loads were highest.

Industrial waste compounded these problems. Butchers discarded offal into rivers, tanners flushed lime-soaked hides and chemical byproducts into open channels, and fullers discharged contaminated wash water from cloth production.13 These activities concentrated pollutants near working waterfronts and downstream residential quarters. Municipal governments attempted to regulate such practices, yet economic necessity often won out over environmental concerns. The cumulative effect of human and industrial waste created heavily fouled stretches of river that could not sustain clean water for domestic use. Archaeological excavations confirm these patterns, with riverbed deposits revealing layers of organic and industrial waste dating to active periods of urban growth.

Cesspits provided an alternative means of waste disposal, but they also posed risks to water sources. Many medieval homes relied on privately dug pits that required periodic emptying by professional waste collectors.14 Improperly constructed or poorly maintained pits leaked into surrounding soil, where waste could infiltrate groundwater and contaminate nearby wells. In densely inhabited neighborhoods, cesspits stood only a short distance from household water sources. Civic authorities issued regulations requiring minimum distances between cesspits and wells, but these standards were inconsistently applied and often ignored when space was limited.

Urban topography intensified the burden on waterways. Streets sloped toward rivers and open drains, carrying refuse and stormwater into channels that lacked filtration or settling mechanisms.15 Wastewater flowed freely across surfaces and accumulated in low lying areas before reaching streams or rivers. Heavy rains accelerated this movement and washed accumulated debris into public water sources. Medieval towns lacked systematic sewage systems, and the interplay of gravity, street layout, and informal waste practices shaped overwhelmingly unsanitary conditions.

The combination of public latrines, private cesspits, and industrial waste made medieval waterways vulnerable to chronic contamination.16 These systems reflected pragmatic attempts to manage human activity within limited technological and infrastructural frameworks. Although officials occasionally issued bans or corrective measures, structural pressures often prevented meaningful change. The result was a hazardous urban environment in which rivers served simultaneously as necessary lifelines and persistent carriers of disease.

Medieval Technical Knowledge: Observations of Clarity, Flow, and Taste

Medieval writers concerned with health and natural philosophy developed systematic ways of evaluating water quality. Their frameworks drew heavily on classical traditions, particularly the Hippocratic and Galenic corpus, which associated certain environmental conditions with bodily well-being. Scholars and practitioners applied these inherited principles to local contexts by assessing water according to its clarity, movement, odor, and taste.17 These criteria appear in medical treatises and practical manuals that guided physicians, civic advisors, and householders in identifying safer sources for consumption. Although sensory evaluation could not detect pathogens, it reflected an empirical approach grounded in observation and experience.

Technical and medical texts describe distinctions between flowing and stagnant waters. Authors working in the Islamic and Latin traditions emphasized that moving water was generally safer than still pools, which were thought to collect impurities. Writers such as al Rhazi and Avicenna, whose works circulated widely in medieval Europe, offered guidance on identifying undesirable qualities such as turbidity, foul smells, or discoloration.18 Their classifications influenced European compendia and commentaries, where scholars adapted earlier insights to Northern climates and urban settings. This intellectual continuity helped integrate environmental assessment into broader discussions of public health.

Urban medical practitioners also relied on experiential knowledge gathered from daily work within towns. Observations of polluted rivers and discolored wells informed treatises that warned against the dangers of using water from compromised sources.19 Physicians recognized that proximity to industrial quarters or waste channels increased the likelihood of contamination. Their recommendations encouraged residents to avoid water that appeared visibly tainted or that carried strong odors, although such guidance could not always be followed in crowded neighborhoods where alternatives were limited. These writings added a practical dimension to scholarly discussions of water quality.

Despite the sophistication of sensory evaluation, medieval observers operated within a conceptual framework that lacked microbial understanding. Their assessments could identify visible or olfactory signs of corruption but could not detect waterborne pathogens.20 The limits of sensory analysis did not diminish its significance, however. The effort to distinguish safe from unsafe water contributed to the intellectual foundations of environmental health. It also provided a vocabulary that civic authorities would later use when regulating water sources. Medieval writers approached water with genuine empirical curiosity, and their insights helped shape subsequent interpretations of disease and sanitation.

Civic Responses and the Rise of Regulation

Municipal governments increasingly confronted the dangers posed by contaminated water as urban populations expanded. Civic records from major towns show that authorities recognized polluted rivers as threats to communal well-being, even if they did not understand the biological mechanisms behind disease. Regulations targeting waste disposal began to appear in city statutes, often responding to visible degradation of rivers and streams that served domestic and industrial needs.21 These ordinances marked some of the earliest attempts to manage environmental hazards through formal governance and reflected growing administrative involvement in urban sanitation.

Authorities directed particular attention to trades that produced large volumes of organic waste. Butchers, tanners, and fishmongers were frequent subjects of municipal legislation because their activities generated materials likely to foul waterways. Records from cities such as London and York imposed restrictions on disposing of animal remains and industrial byproducts into rivers, sometimes pairing prohibitions with financial penalties for violators.22 Although enforcement varied, the existence of such measures demonstrates that civic leaders attempted to curb practices that endangered water supplies. Their interventions reveal a pragmatic approach shaped by the need to balance commercial activity with public welfare.

Civic regulations also addressed domestic sources of contamination. Town governments issued rules governing the placement and maintenance of cesspits, seeking to limit leakage into groundwater and reduce the risk of polluting wells. In some cities, ordinances required householders to keep cesspits at specified distances from public water sources, while others mandated periodic emptying.23 These measures show an awareness that waste management had direct implications for urban health. Municipal attempts to supervise cesspit construction and upkeep indicate that authorities recognized the importance of mitigating contamination within crowded neighborhoods.

Despite these efforts, regulatory measures often faced practical limitations. Rapid population growth strained enforcement capacities, and economic pressures made it difficult for officials to impose strict controls on established trades. Some regulations emerged only after prolonged complaints about pollution or in response to acute crises.24 Nonetheless, the accumulation of ordinances over the later Middle Ages reflects a gradual shift toward more systematic management of urban sanitation. Civic responses laid important groundwork for later public health reforms by articulating connections between environmental conditions and community well-being.

Disease, Urban Mortality, and the Search for Causation

Patterns of illness in medieval towns were closely tied to environmental conditions, particularly the quality of water available to crowded neighborhoods. Chronic contamination of rivers and wells created circumstances in which diarrheal diseases, skin infections, and other waterborne illnesses became regular features of urban life. Physicians and civic observers recognized that outbreaks often appeared in districts where waste accumulated most visibly.25 Although their explanations varied, these accounts reveal a consistent effort to link the physical environment with the spread of disease. Urban mortality patterns reflected the vulnerability of populations that depended on shared and frequently polluted water sources.

Medical writers offered interpretations that blended inherited classical theory with empirical observations of local conditions. Many treatises emphasized the role of corrupted water in producing fevers, digestive disorders, and epidemics, drawing on Hippocratic ideas about the influence of place and season.26 Physicians noted that stagnant or foul smelling water was particularly dangerous and advised communities to avoid sources that displayed discoloration or unusual taste. Their recommendations reveal a growing awareness that polluted environments contributed to sickness, even though the mechanisms remained poorly understood. These texts represent early attempts to conceptualize disease within an environmental framework.

Civic chronicles and administrative records provide additional insight into how communities perceived links between pollution and illness. Complaints about outbreaks often accompanied appeals for stricter waste control, and officials occasionally referenced specific sites known for foul odors or visible contamination.27 These accounts suggest that residents drew connections between environmental degradation and the onset of illness, even if explanations remained grounded in premodern understandings of physiology. The clustering of disease in low lying or densely inhabited districts reinforced perceptions that unsanitary conditions contributed to the intensity and spread of sickness.

Urban mortality also rose during periods of migration, when new arrivals increased both population density and pressure on already strained water systems. Rapid influxes of people into cities such as Florence, London, and Paris placed additional burdens on wells and rivers that were already compromised by industrial and domestic waste.28 Contemporary observers noted the heightened vulnerability of poorer residents, who often lived near polluted water sources and lacked access to cleaner supplies. These demographic pressures made disease a persistent threat and strengthened calls for civic intervention. The difficulties of maintaining sanitary systems in expanding urban environments contributed to cycles of illness that shaped medieval health patterns.

The search for causation unfolded within this context of environmental strain and recurring epidemics. Medical and civic writers did not yet possess microbial theory, but they increasingly recognized that foul environments and contaminated water played a critical role in producing disease. Their attempts to explain illness within an ecological framework laid important intellectual foundations for later developments in public health.29 Even when explanations were incomplete, the effort to understand how contaminated water contributed to sickness represented a significant step toward more systematic approaches to sanitation and disease prevention.

The Formation of Miasma Theory and its Public Health Consequences

Growing concern over foul smells in medieval cities helped shape the development and acceptance of miasma theory. Medical writers, drawing on classical models, argued that putrefaction released harmful vapors that could enter the body and disrupt its humoral balance.30 These ideas, inherited from Galenic and Aristotelian traditions, gained renewed relevance in expanding urban environments where waste accumulation and deteriorating water quality created persistent odors. Physicians interpreted these smells as indicators of corruption, and their writings increasingly emphasized the dangers posed by stagnant or contaminated air. This theoretical framework provided a language through which communities could articulate anxieties about environmental decay.

Civic legislation responded to these developments by targeting the visible and olfactory signs of pollution. Municipal authorities issued ordinances removing noxious trades from crowded districts, relocating tanneries, and prohibiting the dumping of offal or sewage into rivers.31 Officials justified these measures not only on practical grounds but also through the logic of miasma theory, which linked unpleasant smells to disease. These actions reflected a growing conviction that urban health depended on controlling the environmental conditions believed to generate harmful vapors. Although the measures often focused on eliminating odors rather than directly addressing microbial contamination, they marked a shift toward more systematic sanitation policies.

Public health responses grounded in miasma theory also influenced the organization of urban space. Town governments attempted to separate residential areas from industries that produced strong odors, and some cities implemented street cleaning programs aimed at reducing decomposing matter.32 These initiatives varied in scale and consistency, yet they show how environmental theory shaped practical governance. Efforts to maintain cleaner streets and waterways were motivated by the belief that removing sources of putrefaction would diminish the spread of disease. Even when enforcement faltered, the conceptual link between environment and health encouraged communities to view sanitation as a civic responsibility.

Despite its limitations, miasma theory created a framework that supported the expansion of regulatory authority over waste and water management.33 The emphasis on eliminating foul smells encouraged officials to address some of the most visible and harmful forms of pollution, even without an understanding of pathogens. These interventions helped establish long term administrative practices concerned with monitoring environmental conditions. The theory did not provide accurate explanations of disease transmission, yet it fostered practical reforms that contributed to healthier urban environments and laid groundwork for later public health innovations.

Institutional and Structural Responses: Conduits, Cesspits, and Waste Management Systems

Municipalities across medieval Europe increasingly recognized that sanitation required more than occasional regulation. Structural solutions became central to urban management, particularly in growing commercial centers where population density placed continued pressure on water supplies. Conduit systems expanded in cities such as London, Paris, and Bruges, where officials sought to bring cleaner water from distant springs into urban districts.34 These networks distributed water to public cisterns and fountains, offering alternatives to polluted riverbanks. Their construction required significant financial investment, reflecting the value placed on improving access to reliable and comparatively clean water.

Cesspit regulation formed another critical element of urban sanitation. Towns issued ordinances requiring cesspits to be built with specific materials and kept at regulated distances from wells and shared water sources.35 These measures attempted to mitigate infiltration of waste into the groundwater, particularly in densely populated neighborhoods. Some cities employed professional waste collectors who emptied cesspits at regular intervals and transported the material beyond the urban limits. The establishment of such systems suggests growing civic recognition that waste management needed to be organized, supervised, and incorporated into broader public health strategies.

Efforts to manage industrial waste also shaped the development of urban space. Authorities relocated certain trades that posed risks to water quality, placing tanners, dyers, and butchers in districts situated downstream or outside the town walls.36 These decisions often reflected a desire to protect rivers used for household needs, as well as the influence of miasma theory, which associated foul smells with illness. Urban zoning policies evolved to separate noxious trades from residential quarters, revealing how environmental concerns informed urban planning. This separation did not eliminate pollution but redirected it away from areas of concentrated domestic activity.

Street cleaning and drainage improvements further supported sanitation goals by limiting the accumulation of waste in public spaces. Municipal governments invested in periodic removal of refuse and implemented drainage projects designed to move wastewater away from crowded neighborhoods.37 These initiatives reduced the visible presence of decomposing matter and improved the general condition of streets and marketplaces. Although their effectiveness varied according to local resources and administrative capacity, such measures reflect a broader trend toward infrastructural solutions that complemented regulatory efforts aimed at protecting water sources.

The combined development of conduits, cesspit management, industrial zoning, and drainage reform illustrates a gradual institutionalization of sanitation in the medieval world.38 Civic authorities endeavored to create stable frameworks for managing waste and preserving water quality, even within the constraints of contemporary scientific understanding. These structural responses did not eliminate contamination, but they marked a significant shift toward sustained public health planning. Their implementation demonstrates that medieval communities approached environmental challenges with a range of coordinated strategies that laid important groundwork for later public health systems.

Migration, Crowding, and Public Health Pressure

Migration into medieval towns intensified the strain on already vulnerable water systems. As people arrived seeking work, protection, or opportunity, urban populations expanded faster than civic infrastructure could adapt. In many centers, newcomers settled in marginal districts where rents were low and where access to clean water was limited.39 These neighborhoods often developed along riverbanks or near industrial zones, placing residents in close contact with contaminated water sources. The rapid increase in population density heightened exposure to environmental hazards and contributed to recurrent outbreaks of disease.

The accumulation of waste in crowded districts created overlapping challenges for sanitation. Streets filled quickly with refuse, cesspits overflowed, and riverbanks became repositories for household and industrial waste.40 Municipal governments attempted to regulate these conditions, but enforcement proved difficult as urban populations expanded. The pressure placed on limited water resources increased the likelihood that households would draw from polluted wells or river sites. Chronic contamination became a defining feature of many medieval towns, and the combination of dense settlement patterns and inadequate sanitation created conditions favorable to the spread of waterborne illnesses.

Migration also altered the social and economic landscape of cities, influencing how communities responded to environmental threats. Many newcomers worked in trades that relied heavily on water, including brewing, dyeing, tanning, and textile production.41 These industries required significant quantities of water and often discharged waste into the same channels used by households. The expansion of such trades intensified pollution and made it more difficult for civic authorities to balance economic productivity with public health concerns. Urban economies depended on these crafts, yet their environmental impact contributed directly to the degradation of local waterways.

Some cities attempted to manage the pressures of population growth by creating new residential zones or by extending existing neighborhoods. These developments sometimes included efforts to protect water sources, such as relocating polluted industries or improving conduit distribution.42 However, the pace of urban expansion often exceeded the capacity of municipal governance. Newly settled areas frequently lacked adequate drainage or protection from nearby waste channels. As a result, the spatial reorganization of cities did little to reduce the broader risks associated with contaminated water, and environmental problems continued to follow patterns established during earlier phases of urbanization.

The demographic effects of migration were compounded by the cyclical nature of disease. Epidemics such as plague and dysentery struck hardest in densely populated districts where water contamination was most severe. Chronicles and civic reports describe localized mortality spikes in neighborhoods situated near industrial waste sites or compromised wells.43 These patterns underscored the relationship between population density, environmental degradation, and vulnerability to disease. Although medieval observers could not identify pathogens, they recognized that crowded districts faced disproportionate risks, and their accounts reflect growing concern about the spatial distribution of illness within cities.

Despite the challenges posed by rapid migration, the pressures it created played a significant role in shaping long term sanitation policy. The persistent association between crowded districts and high mortality helped convince civic leaders that water quality and waste management required sustained intervention.44 Ordinances targeting waste disposal, improvements to conduit systems, and early forms of urban zoning all emerged partly in response to demographic realities. Migration amplified the dangers of contaminated water, but it also motivated officials to pursue new strategies for protecting public health. These developments contributed to the broader evolution of urban governance and helped create frameworks that later public health reforms would build upon.

Conclusion: Sanitation, Knowledge, and the Long Arc of Public Health

The intertwined problems of contaminated water, industrial waste, and dense settlement patterns shaped the evolution of medieval public health in ways that reveal early attempts to manage environmental risk. Municipal ordinances, medical writings, and infrastructural developments demonstrate that medieval societies confronted the dangers posed by polluted waterways with a mixture of practical measures and theoretical interpretation.45 Although their scientific understanding was limited, communities recognized that deteriorating environmental conditions contributed to illness and mortality. Their responses formed an important part of the broader history of urban governance and public welfare.

Medieval scholars and practitioners contributed to this history by developing observational criteria for assessing water quality. Their reliance on sensory evaluation reflected both the possibilities and constraints of the period. Technical and medical treatises reveal growing attention to the relationship between environmental conditions and human health, even when explanations fell short of identifying microbial causation.46 These efforts did not produce a unified scientific model, but they provided a foundation for later developments by emphasizing the significance of environmental knowledge in addressing disease.

Civic authorities built upon these insights by enacting measures intended to regulate waste, protect water supplies, and reorganize urban space. Their actions were shaped by the pressures of migration, economic growth, and repeated outbreaks of disease.47 Miasma theory offered a conceptual language through which officials justified interventions, linking foul smells to broader concerns about public welfare. Even when enforcement remained inconsistent, the gradual accumulation of ordinances and infrastructural improvements marked a shift toward a more systematic approach to sanitation. These initiatives reveal that medieval urban governance engaged actively with environmental challenges rather than responding passively to crisis.

The medieval experience with contaminated water laid important groundwork for later public health reforms. Although cities lacked the scientific tools to identify pathogens, their efforts to manage waste, protect water sources, and reshape urban environments demonstrated an emerging recognition that health and sanitation were inseparable from the physical conditions of daily life.48 The combination of empirical observation, civic intervention, and evolving environmental theory created a legacy that shaped future approaches to urban health. Medieval public health was not a precursor defined by absence or failure, but a dynamic field in which communities experimented with strategies that informed the long arc of environmental governance and disease prevention.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Carol Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2013), 17–20.

- John Henderson, The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), 34.

- Nancy Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 50–52.

- Martha Carlin, “Medieval English Towns,” in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, vol. 1, ed. D. M. Palliser (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 191–195.

- Luke Demaitre, Medieval Medicine: The Art of Healing, from Head to Toe (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2013), 89–92.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 17–21.

- Bruce L. Venarde, Women’s Monasticism and Medieval Society: Nunneries in France and England, 890–1215 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), 67.

- Mark Leone, “Conduits and Urban Sanitation,” in A History of Water, ed. Terje Tvedt and Richard Coopey (London: I. B. Tauris, 2010), 144–146.

- Paolo Squatriti, Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400–1000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 101–104.

- John Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages (London: Routledge, 2011), 62–63.

- Carlin, “Medieval English Towns,” 191–195.

- Richard Holt, The Mills of Medieval England (Oxford: Blackwell, 1948), 44–45.

- Martha Carlin, Medieval Southwark (London: Hambledon Press, 1996), 112–115.

- Dolly Jørgensen, The Medieval Pig (Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2024), 39–41.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 58–60.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 30–33.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 50–52.

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2013), 220–223.

- Demaitre, Medieval Medicine, 87–90.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 56–58.

- Carlin, “Medieval English Towns,” 191–195.

- Derek Keene, “Issues of Water in Medieval London,” Urban History Vol. 28, No. 2 (2001): 161-179.

- Jørgensen, The Medieval Pig, 41–43.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 61–63.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 35–38.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 54–57.

- Carlin, Medieval Southwark, 118–121.

- John Henderson, Florence Under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 44–47.

- Demaitre, Medieval Medicine, 92–94.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine, 229–232.

- Keene, “Issues of Water in Medieval London,” 144–147.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 70–73.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 64–66.

- Leone, “Conduits and Urban Sanitation,” 144–146.

- Jørgensen, The Medieval Pig, 41–46.

- Carlin, “Medieval English Towns,” 191–195.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 72–74.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 66–68.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 70–72.

- Jørgensen, The Medieval Pig, 48–51.

- Carlin, Medieval Southwark, 122–124.

- Leone, “Conduits and Urban Sanitation,” 147–149.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 82–85.

- Keene, “Issues of Water in Medieval London,” 150–153.

- Carlin, “Medieval English Towns,” 191–195.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 50–52.

- Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies, 70–73.

- Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages, 66–68.

Bibliography

- Aberth, John. An Environmental History of the Middle Ages: The Crucible of Nature. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Carlin, Martha. Medieval Southwark. London: Hambledon Press, 1996.

- —-. “Medieval English Towns.” In The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, vol. 1, edited by D. M. Palliser, 191–195. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Demaitre, Luke. Medieval Medicine: The Art of Healing, from Head to Toe. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2013.

- Henderson, John. Florence Under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

- Henderson, John. The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

- Holt, Richard. The Mills of Medieval England. Oxford: Blackwell, 1948.

- Jørgensen, Dolly. The Medieval Pig. Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2024.

- Keene, Derek. “Issues of Water in Medieval London.” Urban History Vol. 28, No. 2 (2001): 161-179.

- Leone, Mark. “Conduits and Urban Sanitation.” In A History of Water, edited by Terje Tvedt and Richard Coopey, 144–149. London: I. B. Tauris, 2010.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Rawcliffe, Carol. Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2013.

- Siraisi, Nancy. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Squatriti, Paolo. Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400–1000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Venarde, Bruce L. Women’s Monasticism and Medieval Society: Nunneries in France and England, 890–1215. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.