Seen from the present, Shaw and Marven stand not as relics of an immature republic but as enduring figures within an unfinished one.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Corruption, Silence, and the Fragile Republic

The United States did not begin as a settled or confident republic. In the years following independence, Americans lived with a pervasive fear that the hard-won victory over imperial power could be undone not by foreign invasion, but by internal decay. Corruption, secrecy, and the unchecked authority of officeholders loomed large in the political imagination of the new nation. The Revolution had been fought not only against British rule, but against the habits of governance that allowed power to operate without accountability.1 The central question facing the early republic was therefore not merely how to govern, but how to prevent authority from quietly reproducing the abuses it claimed to have overthrown.

This anxiety was especially acute within the military. Standing armies and navies had long been associated with tyranny in Anglo-American political thought, and the concentration of power in officers far from civilian oversight was viewed as inherently dangerous.2 Yet the realities of war and international insecurity required the maintenance of armed forces, placing republican ideals in constant tension with practical necessity. Discipline, hierarchy, and obedience were indispensable, but so too was the expectation that officers remained servants of the public rather than masters over it. In this unstable balance, silence in the face of wrongdoing could itself become a form of betrayal.

It was within this context that America’s first whistleblowers emerged. Long before the term existed, Samuel Shaw and Richard Marven confronted a dilemma that would become a recurring feature of American political life. To expose misconduct was to risk one’s career, reputation, and livelihood. To remain silent was to accept that the new republic might tolerate the very abuses it claimed to reject. Their decision to speak was neither theatrical nor ideological. It was grounded in a conviction that loyalty to the republic required something more demanding than obedience to superiors.3

The significance of Shaw and Marven lies not simply in the scandal they revealed, but in what their actions exposed about the early American understanding of accountability. Whistleblowing did not arise as an adversarial practice aimed at undermining the state. It emerged as a civic obligation, rooted in revolutionary notions of virtue, transparency, and public trust.4 The act of disclosure was framed not as insubordination, but as fidelity to the principles that justified independence in the first place.

By examining the case of Samuel Shaw and Richard Marven, what follows traces the origins of whistleblowing to the fragile moral architecture of the early republic. Their story reveals how deeply the survival of American self-government depended on individuals willing to disrupt silence, challenge authority, and accept personal cost in defense of institutional integrity. The struggle between corruption and accountability did not begin in modern bureaucracies. It was present at the nation’s founding, when the future of republican governance remained uncertain and easily undone.

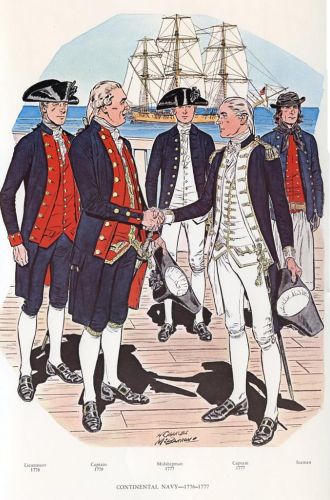

The Revolutionary Context: Honor, Duty, and Military Authority

The Revolutionary generation inherited a deep suspicion of standing armies that predated independence itself. Anglo-American political culture long associated permanent military forces with despotism, corruption, and the erosion of civic liberty. This suspicion drew on English Whig thought, colonial experience under British garrisons, and classical republican warnings that armed professionals detached from civil society posed an existential threat to free government.5 The Revolution did not erase these fears. It intensified them by placing military power at the center of a political experiment that claimed legitimacy from popular sovereignty rather than coercion.

Yet the demands of war forced an uneasy accommodation. The Continental Army and the fledgling Continental Navy required discipline, hierarchy, and obedience to function at all. Officers were expected to command decisively, enforce order, and maintain authority over men drawn from disparate colonies and social backgrounds. Military authority thus became both indispensable and suspect. The republican solution was not to deny hierarchy, but to moralize it. Authority was tolerated only so long as it was exercised in service of the public good rather than personal ambition.6

Honor functioned as the ethical bridge between power and restraint. Revolutionary officers were expected to embody a civic ideal in which personal reputation, virtue, and public trust were inseparable. Honor was not merely social standing. It was a moral currency that linked private conduct to public legitimacy. An officer who abused power, mistreated subordinates, or acted beyond lawful authority did not simply violate regulations. He threatened the moral foundation upon which republican military command rested.7

Duty, in this framework, extended beyond obedience to superiors. Revolutionary political thought insisted that loyalty ultimately ran upward to the people and the principles for which the Revolution had been fought. Officers were servants of the republic, not autonomous wielders of force. This conception created an inherent tension. Obedience was necessary for military effectiveness, yet blind obedience risked reproducing the very abuses associated with imperial rule. The ethical burden placed on officers was therefore unusually heavy, requiring constant judgment rather than mechanical compliance.8

The absence of mature institutional oversight magnified these tensions. Early American military structures lacked clear mechanisms for internal accountability, independent inspection, or protected channels of complaint. Civilian authorities exercised theoretical control, but distance, slow communication, and political fragmentation limited effective supervision. In practice, much depended on individual character. When authority failed, there were few safeguards beyond the willingness of officers and sailors to speak against it, often at considerable personal risk.9

In this moral and institutional landscape, whistleblowing became thinkable, even if unnamed. The decision to report misconduct was not an innovation imposed from outside military culture. It emerged from within the revolutionary understanding of honor and duty itself. To remain silent in the face of abuse could constitute complicity. To speak was dangerous, but it could also be framed as fidelity to republican ideals. Shaw and Marven’s actions would draw their meaning from this context, where authority was legitimate only when restrained by conscience and accountable to the public it claimed to serve.

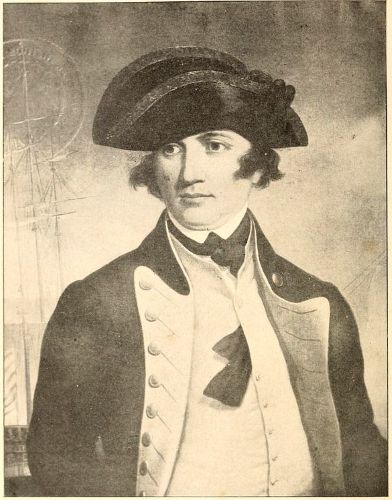

Commodore Esek Hopkins and the Abuse of Naval Power

Esek Hopkins was appointed the first commander in chief of the Continental Navy in December 1775, a position that placed extraordinary authority in his hands at a moment when naval oversight barely existed. Congress granted Hopkins wide discretion, authorizing him to harass British forces along the American coast but leaving operational details largely to his judgment. In practice, this latitude reflected both necessity and uncertainty. The new republic lacked naval tradition, administrative depth, and clear chains of accountability, making trust in individual commanders unavoidable.10

That trust soon frayed. Hopkins ignored explicit congressional instructions to clear British ships from the Chesapeake and Carolina coasts, instead leading an expedition to the Bahamas in pursuit of military supplies. While the raid captured valuable matériel, it also signaled a troubling pattern of unilateral decision-making. Subsequent complaints accused Hopkins of mistreating prisoners, abusing subordinates, and exercising authority in ways that exceeded both legal mandate and republican restraint.11 These actions were not isolated misjudgments but part of a broader erosion of confidence among officers and crew.

The nature of Hopkins’s misconduct exposed the structural fragility of early American naval power. Command at sea was inherently distant from civilian supervision, and communications delays made real-time oversight impossible. In this environment, the line between initiative and insubordination blurred easily. Hopkins’s defenders framed his actions as necessary assertiveness in wartime, while critics argued that unchecked discretion threatened to reproduce the very abuses associated with British naval rule.12 The debate was not merely personal. It was constitutional in spirit, touching on whether republican authority could survive without enforceable limits.

What made the situation especially volatile was the absence of protected avenues for complaint. Officers who challenged Hopkins did so without assurance of due process or immunity from retaliation. To accuse a superior officer was to invite professional ruin, social ostracism, and charges of disloyalty. It was within this atmosphere of fear and uncertainty that Samuel Shaw and Richard Marven chose to act. Their decision to report Hopkins’s abuses did not arise from ideological extremism, but from the recognition that silence would render republican ideals meaningless in practice.13

Samuel Shaw and Richard Marven: Profiles of Conscience

Shaw and Marven were not marginal figures within the Revolutionary naval world, nor were they predisposed to dissent. Shaw served as a Marine officer aboard the Continental Navy’s flagship, while Marven held command responsibilities as a naval captain. Both men occupied junior but respectable positions within a fragile and highly politicized military hierarchy, and neither had established a public reputation for insubordination or ideological agitation prior to their confrontation with Commodore Hopkins.14 Their service records reflected competence rather than controversy, making their later actions all the more striking.

Their professional circumstances heightened the risks they faced. Advancement in the Continental Navy depended heavily on reputation, patronage, and personal relationships, particularly given the absence of a standardized promotion system. Officers who attracted negative attention from superiors could find themselves stalled or removed with little recourse. To challenge a commander with congressional allies was therefore to jeopardize not only one’s career trajectory but one’s social standing within a tightly interconnected officer corps.15 In this environment, silence was often the safer course.

What compelled Shaw and Marven to speak was not disagreement over strategy or policy, but direct exposure to conduct they regarded as abusive and illegitimate. They objected to Hopkins’s treatment of prisoners, his retaliatory actions against subordinates, and his broader misuse of authority, framing these actions as violations of the moral constraints that republican command was supposed to observe.16 Their complaints did not question the necessity of discipline or hierarchy. They questioned whether authority exercised without restraint could remain compatible with the principles for which the Revolution had been fought.

Hopkins’s response demonstrated the vulnerability of those who challenged power. Using his authority, he dismissed both Shaw and Marven from service, effectively silencing their accusations and signaling to others the cost of dissent.17 At a moment when no formal protections existed for officers who reported misconduct, such retaliation carried severe consequences. Removal from service meant loss of income, damage to reputation, and exclusion from future advancement, reinforcing the structural incentives that discouraged accountability.

Yet Shaw and Marven persisted, appealing beyond their immediate chain of command to the Continental Congress itself. Their willingness to endure professional ruin in defense of public accountability transformed their actions into something more than personal grievance. It marked them as participants in a civic ethic that prioritized the integrity of republican institutions over individual security. In choosing conscience over convenience, they established an early model of whistleblowing rooted not in opposition to the state, but in fidelity to its founding ideals.18

The Act of Disclosure: Risking Career and Reputation

The decision to formally accuse a superior officer was extraordinary within the Revolutionary naval world. Shaw and Marven did not act impulsively or anonymously. They submitted their allegations directly to the Continental Congress, detailing Hopkins’s mistreatment of prisoners and retaliatory conduct toward subordinates.19 This choice reflected an understanding that ordinary military channels offered no meaningful remedy. By bypassing Hopkins’s authority entirely, they placed their faith in civilian oversight at a time when its reach was uncertain and its protections untested.

Such disclosure carried immediate and predictable risks. The Continental Navy was small, politicized, and deeply personal in its operations. Officers knew one another, reputations traveled quickly, and patronage mattered more than formal procedure. To accuse a commander with congressional allies was to invite swift reprisal, particularly in an institution where loyalty was often conflated with silence.20 Shaw and Marven were fully aware that Congress might choose expediency over principle, leaving them exposed to retaliation without recourse.

Hopkins responded exactly as feared. He dismissed both men from service, framing their accusations as insubordination rather than civic duty.21 The removal functioned as a warning to others who might consider similar action. Without formal whistleblower protections or guarantees of due process, Shaw and Marven’s professional lives were effectively placed on hold. Their experience revealed how easily republican rhetoric could yield to personal power when institutional safeguards were weak or absent.

What distinguished their disclosure, however, was its framing. Shaw and Marven did not present themselves as aggrieved subordinates seeking redress, but as officers fulfilling an obligation to the public. In appealing to Congress, they invoked the authority of the people rather than the hierarchy of command, insisting that military power remained accountable to civilian judgment.22 Their action exposed a foundational tension within the early republic: whether loyalty meant obedience to superiors or fidelity to the principles that justified independence itself.

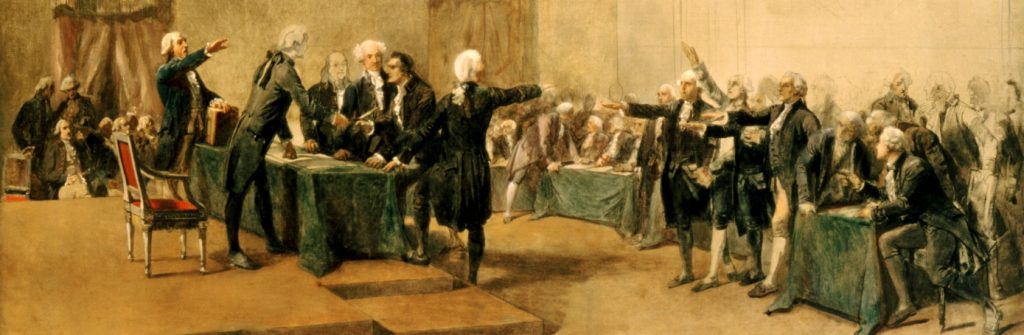

Congressional Response: Accountability over Authority

The Continental Congress did not initially move swiftly or decisively in response to Shaw and Marven’s disclosures. Members faced competing pressures: the need to preserve naval effectiveness during wartime, personal and regional loyalties to Commodore Hopkins, and the broader question of how far civilian authority should intrude into military affairs. Congressional deliberations unfolded amid uncertainty about precedent. No clear model existed for disciplining senior officers accused by subordinates, and the risk of undermining command authority weighed heavily on the proceedings.23

Despite these hesitations, Congress ultimately chose investigation over deference. Committees were convened to examine the charges against Hopkins, drawing on testimony, correspondence, and prior complaints that had circulated informally within naval circles.24 The process exposed not only specific abuses but the structural weaknesses of early naval administration. Congressional scrutiny transformed what might have remained an internal dispute into a public question of republican accountability, shifting the locus of authority away from personal command and toward institutional judgment.

The findings placed Congress in an uncomfortable but revealing position. While acknowledging Hopkins’s earlier service and the material gains of the Bahamian expedition, legislators could not ignore evidence of misconduct and retaliation. The issue was no longer one of military competence alone. It was whether a republic founded on resistance to arbitrary power could tolerate similar behavior within its own institutions. In weighing this question, Congress signaled that authority derived from office did not confer immunity from oversight.25

Crucially, Congress also addressed the treatment of the whistleblowers themselves. In a series of resolutions, legislators affirmed that officers had not only the right but the duty to report misconduct to civilian authorities.26 This declaration reframed Shaw and Marven’s actions as acts of loyalty rather than insubordination, establishing a moral hierarchy in which fidelity to the republic superseded obedience to individual commanders. Although limited in immediate practical effect, the language marked a significant conceptual shift.

The congressional response did not resolve all tensions between military authority and civilian control, nor did it eliminate retaliation as a practical risk. Yet it established a foundational principle: accountability was not an external constraint imposed on the armed forces, but an internal requirement of republican legitimacy. In siding with Shaw and Marven, Congress articulated an early vision of whistleblowing as a civic obligation embedded within democratic governance rather than a threat to it.27

The 1778 Resolution: America’s First Whistleblower Protection

On July 30, 1778, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution that articulated, for the first time in American history, a formal duty to report official misconduct. The resolution declared that it was the obligation of all persons in the service of the United States to inform Congress of any wrongdoing by officers or agents acting under its authority.28 This language was striking not only for its clarity but for its inversion of traditional military norms. Rather than treating disclosure as a breach of loyalty, Congress framed it as a positive civic responsibility grounded in republican governance.

The resolution’s significance lay less in its immediate enforcement mechanisms than in its moral logic. Congress did not merely tolerate whistleblowing. It elevated truth-telling above hierarchical obedience, explicitly affirming that allegiance to the public outweighed deference to individual officeholders.29 In doing so, legislators embedded accountability within the structure of authority itself. The state was not portrayed as weakened by internal criticism but strengthened by the exposure of abuse. This conception stood in sharp contrast to European military traditions, where disclosure outside the chain of command was typically treated as mutiny or sedition.

Yet the protections offered by the resolution remained largely aspirational. Congress lacked the administrative capacity to enforce its principles consistently, and retaliation against whistleblowers continued to occur in practice. Shaw and Marven’s own experience underscored this gap between declaration and reality. Still, the resolution established a durable precedent. It articulated a foundational principle that would resurface across centuries of American political conflict: that the legitimacy of authority depends not on silence, but on the willingness of individuals to speak when power exceeds its bounds.30

Retaliation, Rehabilitation, and Uneven Justice

The immediate aftermath of disclosure was punitive rather than protective. Despite Congress’s growing unease with Hopkins’s conduct, Shaw and Marven remained dismissed from service, their reputations damaged by the stigma of insubordination. In the tightly interconnected world of Revolutionary military service, removal carried consequences beyond loss of pay. It marked an officer as unreliable and politically dangerous, discouraging future appointments and eroding networks of patronage essential to advancement.31 Retaliation thus functioned less as formal discipline than as an informal warning mechanism, reinforcing silence even as Congress debated accountability.

Over time, congressional sentiment shifted more clearly against Hopkins. Continued complaints, corroborating testimony, and the accumulation of administrative failures weakened his political defenses. Congress ultimately suspended and then dismissed him from command, acknowledging that his behavior had exceeded acceptable bounds.32 Yet this outcome did not immediately restore Shaw and Marven. Vindication of principle did not translate smoothly into personal rehabilitation, revealing a persistent asymmetry in how institutions corrected abuses. Authority could be removed more easily than reputations repaired.

Shaw and Marven were eventually reinstated, but the process was slow and incomplete. Congressional resolutions affirmed their conduct as justified, and back pay was authorized to compensate for lost service.33 Still, reinstatement could not fully erase the professional damage already done. Time lost from service, stalled careers, and lingering suspicion limited their prospects in ways that formal declarations could not remedy. The republic had acknowledged the rightness of their actions, but it lacked the institutional capacity to make them whole.

This uneven outcome exposed a central paradox of early American whistleblowing. The state could articulate lofty principles of accountability while remaining structurally incapable of protecting those who acted on them. Shaw and Marven’s experience demonstrated that moral clarity did not guarantee material justice. Yet their partial rehabilitation mattered nonetheless. It established that retaliation was not the final word, and that public acknowledgment of wrongdoing could alter outcomes, even if imperfectly. In this tension between principle and practice lay the enduring challenge of whistleblowing in a republic still learning how to govern itself.34

Whistleblowing as Republican Practice, Not Bureaucratic Exception

The actions of Shaw and Marven were not anomalies within Revolutionary political culture. They emerged from a broader republican ethic that treated vigilance against corruption as a civic duty rather than a procedural inconvenience. Eighteenth-century republican thought, shaped by classical and early modern sources, warned repeatedly that unchecked power invited decay. Public virtue depended on the willingness of citizens and officeholders alike to expose abuses before they hardened into habit.35 In this context, whistleblowing was not oppositional. It was preservative.

Revolutionary Americans inherited deep suspicions of standing authority, particularly in military institutions. British rule had been experienced not merely as distant governance but as a system sustained by unaccountable officials and insulated command structures. Republican reformers therefore insisted that power remain porous to scrutiny, even during wartime.36 Shaw and Marven’s disclosures aligned with this logic. Their appeal to Congress reflected an expectation that civilian oversight was not an emergency measure but a permanent feature of legitimate authority.

What distinguished this early republican model from later bureaucratic frameworks was its moral rather than procedural emphasis. Whistleblowing did not depend on formal reporting channels, statutory protections, or institutional compliance regimes. It depended on conscience, reputation, and public judgment.37 The legitimacy of disclosure rested on motive and substance rather than adherence to process. This placed heavy burdens on individuals while offering limited guarantees in return, but it also grounded accountability in civic virtue rather than administrative permission.

Over time, this ethic would be narrowed and formalized, transformed into regulatory compliance rather than republican obligation. Yet the example of Shaw and Marven reminds us that whistleblowing originated not as an exception carved out within bureaucratic systems, but as a foundational practice of self-government. To speak against abuse was to participate in the republic itself, affirming that authority existed to serve the public rather than shield itself from scrutiny.38

Long Shadows: From Shaw and Marven to Modern Whistleblowers

The precedent established by Shaw and Marven did not fade with the Revolutionary generation. Their case entered American political memory as an early demonstration that loyalty to the republic could require defiance of authority. Subsequent generations would encounter similar dilemmas as the federal state expanded, particularly during periods of war and administrative consolidation. The basic tension remained constant: whether disclosure of wrongdoing constituted betrayal or civic obligation.39 While the institutional context changed, the moral grammar of whistleblowing endured.

Nineteenth-century whistleblowers confronted a government increasingly defined by bureaucracy rather than personal command. As federal agencies professionalized, misconduct became less visible and more difficult to challenge. Still, Congress periodically reaffirmed the principle that exposure of fraud and abuse served the public interest, most notably through statutes protecting informants who reported corruption within government contracting.40 These measures echoed the logic of 1778, even as they translated moral expectation into legal form.

The twentieth century intensified these conflicts. The rise of the national security state narrowed acceptable boundaries of disclosure, particularly during wartime and the Cold War. Whistleblowers who revealed classified misconduct were often portrayed as threats to national survival rather than guardians of constitutional principle.41 Yet defenders of disclosure continued to invoke Revolutionary precedent, arguing that secrecy unchecked by accountability posed dangers equal to those of foreign adversaries. The question was no longer whether whistleblowing was legitimate, but under what conditions it could be tolerated.

Modern whistleblowers operate within a far more elaborate legal environment, one that promises protection while often delivering retaliation through subtler means. Career derailment, legal jeopardy, and social isolation remain common outcomes, even when disclosures are later validated.42 This continuity underscores the limits of formal safeguards. Statutes can recognize rights, but they cannot eliminate the personal costs of challenging entrenched power. In this respect, Shaw and Marven’s experience remains disturbingly familiar.

What distinguishes contemporary cases is scale rather than substance. Digital records, global media, and instantaneous dissemination amplify the impact of disclosure while magnifying the risks faced by those who speak. The whistleblower is no longer a marginal figure appealing quietly to Congress, but a public actor whose actions reverberate internationally.43 Yet the underlying ethical claim remains unchanged: that authority derives its legitimacy from accountability, not concealment.

Shaw and Marven cast a long shadow across American political life. They remind us that whistleblowing is not a modern aberration born of technological excess or partisan conflict. It is an enduring feature of republican governance, rooted in the conviction that power must remain answerable to the people it serves. The republic’s survival has always depended not on silence, but on the courage of those willing to speak when silence becomes complicity.44

Conclusion: Truth-Telling and the Burden of Republican Freedom

The story of Samuel Shaw and Richard Marven exposes a truth often obscured by celebratory narratives of American origins. Republican government did not emerge fully formed, nor did it automatically protect those who acted in its name. It required individuals willing to test its commitments under conditions of uncertainty and personal risk. Shaw and Marven did not benefit from robust institutions or settled norms. They confronted a republic still improvising its relationship to power, accountability, and dissent. Their actions revealed that freedom, if it was to mean anything more than rhetoric, demanded sacrifice from those who took its principles seriously.45

Their experience also clarifies what republican liberty is not. It is not comfort, safety, or assurance of vindication. The early republic offered none of these reliably. Instead, liberty functioned as a moral burden placed on citizens and officeholders alike. To govern oneself required vigilance, and vigilance required speech. Silence, while often safer, carried its own costs, allowing power to detach itself from justification. Shaw and Marven’s disclosures demonstrate that truth-telling was not ancillary to republican freedom. It was one of its operating conditions.46

The uneven justice they encountered should not be read as evidence of failure alone. It reflects the persistent tension between ideals and institutions that characterizes democratic governance in every era. The republic could recognize wrongdoing and still struggle to repair its consequences. It could affirm principles while lacking the capacity to enforce them consistently. This gap did not negate the significance of whistleblowing. It defined its necessity. Without individuals willing to act before systems were ready, accountability would remain permanently deferred.47

Seen from the present, Shaw and Marven stand not as relics of an immature republic but as enduring figures within an unfinished one. Their legacy reminds us that freedom is sustained not by declarations alone, but by acts that expose abuse at personal cost. Republican government survives only when citizens accept the burden of truth-telling, even when institutions lag behind principle. The courage to speak, rather than the comfort of silence, remains the quiet price of self-rule.48

Appendix

Footnotes

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 229–284.

- J.G.A. Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975), 506–543.

- U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 10 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 732–734.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 403–418.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 330–360.

- Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment, 506–543.

- Joanne B. Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 3–38.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 414–447.

- James Kirby Martin and Mark Edward Lender, A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763–1789 (Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1982), 145–178.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1905), 378–380.

- Charles Oscar Paullin, The Navy of the American Revolution: Its Administration, Its Policy, and Its Achievements (Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1906), 79–92.

- Ray Raphael, A People’s History of the American Revolution (New York: New Press, 2001), 247–250.

- U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 10, 732–734.

- Paullin, The Navy of the American Revolution, 94–101.

- Martin and Lender, A Respectable Army, 162–168.

- U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 10, 732–734.

- Freeman, Affairs of Honor, 57–61.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 259–265.

- U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 10, 732–734.

- Martin and Lender, A Respectable Army, 168–173.

- Paullin, The Navy of the American Revolution, 101–106.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 418–425.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 10 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 720–728.

- Paullin, The Navy of the American Revolution, 106–113.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 425–432.

- U.S. Continental Congress, “Resolution on Reporting Misconduct,” July 30, 1778, in Journals of the Continental Congress, vol. 11 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 732–733.

- The Machiavellian Moment, 547–551.

- U.S. Continental Congress, “Resolution on Reporting Misconduct,”, 732–733.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 432–436.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 345–352.

- Freeman, Affairs of Honor, 61–68.

- Paullin, The Navy of the American Revolution, 113–118.

- U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 11 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 733–735.

- Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 265–270.

- Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment, 506–515.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 55–93.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 418–425.

- Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (New York: Viking Press, 1963), 181–188.

- Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 286–292.

- U.S. Congress, “False Claims Act,” 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729–3733 (originally enacted 1863).

- Daniel Ellsberg, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers (New York: Viking Press, 2002), 3–15.

- Alford, C. Fred, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 17–34.

- Yochai Benkler, Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 281–287.

- Arendt, On Revolution, 181–188.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic607–615.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 319–331.

- Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment, 550–556.

- Arendt, On Revolution, 223–230.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Benkler, Yochai. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Ellsberg, Daniel. Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. New York: Viking Press, 2002.

- Freeman, Joanne B. Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Martin, James Kirby, and Mark Edward Lender. A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763–1789. Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1982.

- Paullin, Charles Oscar. The Navy of the American Revolution: Its Administration, Its Policy, and Its Achievements. Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1906.

- Pocock, J.G.A. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- United States Congress. False Claims Act, 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729–3733. Originally enacted 1863.

- United States Continental Congress. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Vols. 3, 10, 11. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1905–1908.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

- —-. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.