Rome’s warning lies not in tyranny, but in normalization. The quiet death of civic law occurs when legality remains visible but restraint does not.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Law, Power, and the Illusion of Continuity

Roman law has long been celebrated as one of antiquity’s most enduring achievements, admired for its procedural sophistication, conceptual clarity, and extraordinary afterlife in later legal traditions. From the Twelve Tables through the mature Republic, Romans understood law as a civic framework that mediated power, constrained magistrates, and defined the reciprocal obligations between state and citizen. Legal process was not merely technical; it was performative and moral, reinforcing the idea that authority flowed through publicly recognizable procedures. Even violence, when sanctioned, was expected to conform to formal rules and collective oversight. This self-conception did not disappear with the emergence of imperial rule. Emperors, senators, and jurists alike continued to speak the language of legality, tradition, and restoration, presenting Roman law as an unbroken inheritance rather than a transformed instrument of governance.

The central paradox of imperial Rome is that law appeared to remain intact even as its practical force eroded. Courts continued to function, magistracies retained familiar titles, and legal reasoning flourished in juristic writing. Legal education expanded, commentaries multiplied, and appeals to precedent remained central to political legitimacy. Yet beneath this surface continuity, enforcement increasingly shifted away from civic legal process toward administrative discretion. Authority flowed not from publicly accountable procedures, but from imperium exercised through mandates, commands, and delegated power. The result was not the abolition of law, but its internal reinterpretation by those who wielded coercive authority.

This transformation was neither abrupt nor openly acknowledged. Roman political culture prized continuity and abhorred the language of rupture. Successive regimes presented their innovations as restorations, corrections, or necessary adaptations to crisis. Emergency measures were framed as temporary responses to instability, even when they produced lasting precedents. Civil war, internal unrest, and the rhetoric of survival created a political environment in which extraordinary authority could be justified repeatedly without ever being formally normalized. Over time, repetition itself did the work of normalization, quietly altering expectations about where legality truly resided.

The erosion of civic law was most visible not in constitutional proclamations, but in its everyday consequences. Protections once understood as fundamental became conditional, dependent on administrative judgment rather than procedural guarantee. The sanctity of the household, long treated as a cornerstone of Roman civic order, proved especially vulnerable as officials asserted the right to enter, search, and seize in the name of loyalty, security, or public order. Appeals and reviews increasingly flowed upward within administrative hierarchies rather than outward to independent civic bodies. Legality came to mean conformity with state-defined necessity rather than adherence to stable legal standards. Rome thus illustrates how law does not collapse through dramatic repeal, but is hollowed out through reinterpretation, until continuity itself becomes the illusion that masks the quiet triumph of administrative power.

The Roman Household as Legal Sanctuary

In Republican Rome, the household was not conceived merely as a private refuge from public life, but as a legally and symbolically protected unit embedded within the civic order. The domus functioned as a foundational space of Roman identity, linking family, property, religion, and status into a single juridical framework. It was within the household that Roman citizens exercised authority, fulfilled religious obligations, and reproduced social hierarchy. The law treated this space with particular reverence, recognizing that civic stability depended in part on the autonomy and integrity of domestic life.

Central to this legal structure was the authority of the paterfamilias, whose control over the household was extensive yet normatively bounded. His power over children, dependents, and property was recognized by law, but it was not conceived as arbitrary sovereignty. Rather, it operated within a dense web of social expectation, customary restraint, and legal principle that distinguished domestic authority from public coercion. The household was understood as a site of governance, but one governed according to its own internal norms rather than direct state supervision. This distinction mattered because it established a clear boundary between civic magistracy and private jurisdiction. State officials possessed immense power in public spaces, yet were expected to respect the household as a domain in which authority was already properly ordered and therefore not ordinarily subject to intrusion.

The sanctity of the household was further reinforced by its religious dimensions, which gave legal protections a sacred character that went beyond procedural rules. Domestic cults centered on the lares, penates, and ancestral spirits bound the household to Rome’s religious order and, by extension, to the moral legitimacy of the state itself. These rituals were not peripheral practices but central expressions of Roman piety, performed daily and tied to notions of continuity, memory, and obligation. To violate the household was therefore to disrupt more than property or privacy. It risked offending the gods, dishonoring ancestors, and undermining the moral foundations of civic life. Law and religion thus worked together to naturalize the idea that the household stood as a protected threshold, one that power crossed only under exceptional and formally justified circumstances.

This sanctuary was never absolute. Even in the Republic, extraordinary situations such as accusations of treason, sacrilege, or grave threats to public order could justify intrusion. What distinguished the Republican framework was not the impossibility of state entry, but the presumption against it and the expectation of formal legal process when it occurred. Intrusion was framed as an exception that required justification, oversight, and accountability. The household’s protection rested on disciplined restraint rather than the absence of authority. That presumption would prove increasingly fragile as Rome moved toward administrative governance, where justification itself became internal to power and the boundary between exception and norm gradually dissolved.

Republican Legal Process and Its Limits

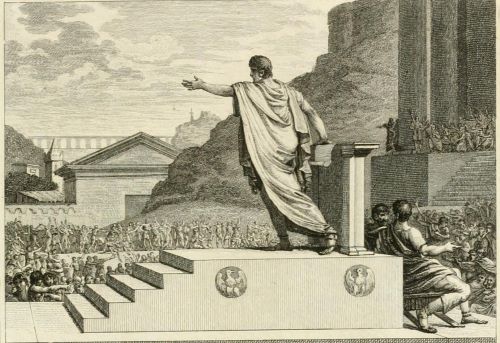

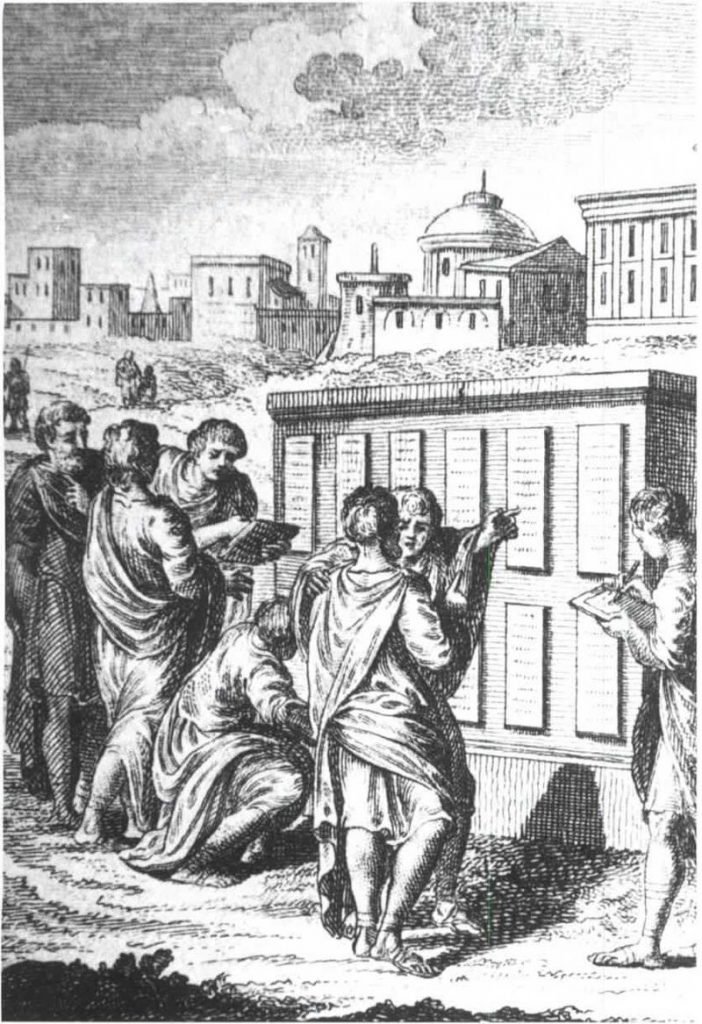

The Roman Republic rested on a strong normative commitment to legal process as the legitimate mediator of power. Magistrates possessed authority, but that authority was expected to operate within publicly recognizable procedures that emphasized accusation, deliberation, and judgment. Courts, assemblies, and collegial offices functioned not merely as mechanisms of governance, but as visible assurances that power was being exercised lawfully. Even when outcomes favored elites, procedural form mattered because it sustained the fiction and the practice of civic consent. Legality drew its strength from the expectation that coercion would be justified through shared institutions rather than imposed through unilateral command.

This proceduralism reflected a broader political culture that treated law as a civic performance embedded in public life. Trials unfolded before audiences, accusations followed ritualized forms, and verdicts were rendered in ways that reinforced the visibility of judgment. Legal conflict was therefore not only about outcomes, but about reaffirming the norms that bound citizens to the state. Even punitive measures such as exile or confiscation were framed as the culmination of collective decision-making rather than personal will. The insistence on formality created a powerful expectation that authority would explain itself, defend itself, and submit itself to recognizable standards. In this sense, procedure functioned as both a practical mechanism and a moral language through which power justified its legitimacy.

Yet this system revealed its fragility during moments of acute crisis. Civil violence, military emergency, and political instability strained deliberative mechanisms and encouraged appeals to necessity. Magistrates turned to extraordinary authority when normal procedures seemed too slow or ineffective. Though such measures were formally exceptional, each invocation weakened the boundary between ordinary law and emergency power, subtly recalibrating expectations about when procedure could be set aside.

The deeper limitation of Republican legal process lay not in corruption or incompetence, but in its dependence on restraint and shared assumptions about limits. Emergency powers were justified as temporary defenses of the Republic, but their repetition created a precedent logic that normalized suspension without abolishing form. Legality remained intact in language and structure even as its constraining force diminished. Authority increasingly rested on political judgment about necessity rather than on procedural guarantees. The Republic thus illustrates how a system devoted to law can undermine itself incrementally, not by rejecting process outright, but by allowing exception to reshape the meaning of legality itself.

Crisis, Emergency, and the Expansion of Imperium

From the late Republic onward, Rome was marked by a near-constant sense of crisis. Foreign wars, internal revolts, economic instability, and factional violence created a political atmosphere in which emergency became not the exception but a recurring condition of governance. In this environment, imperium, the supreme authority vested in magistrates and commanders, expanded in both scope and justification. Originally conceived as a defined power exercised within legal and temporal limits, imperium increasingly functioned as a flexible instrument for responding to perceived threats to order, stability, and survival.

The Republic had long possessed mechanisms for extraordinary authority, most notably the dictatorship, which allowed for the temporary concentration of power during moments of grave danger. In theory, these measures were carefully bounded by duration, purpose, and the expectation of restoration to normal civic governance. In practice, however, repeated reliance on emergency authority undermined confidence in those boundaries. Each invocation demonstrated that legality could be suspended without dismantling the political system that claimed to safeguard it. Emergency power thus acquired a paradoxical legitimacy: it was justified as a defense of law while simultaneously weakening law’s procedural constraints. Over time, crisis ceased to be an anomaly and became a political resource, invoked to authorize actions that would have been unthinkable under ordinary circumstances.

Civil war intensified this dynamic dramatically and permanently altered Roman expectations about authority. The conflicts of the first century BCE collapsed the distinction between military command and civic governance, as generals exercised imperium not only over armies but over cities, provinces, and civilian populations. Proscriptions, mass confiscations, and summary punishments were justified as necessities of survival rather than as violations of law. These actions were rhetorically framed as temporary expedients, yet they produced durable precedents that reshaped the relationship between power and legality. The Republic endured these episodes formally intact, but each crisis expanded the range of actions considered acceptable when order was perceived to be at stake.

What made this expansion especially consequential was its cumulative and self-reinforcing character. Emergency powers were rarely relinquished in full once the immediate threat subsided. Instead, they remained embedded in institutional memory as available tools of governance. Magistrates learned that necessity could substitute for procedure, while citizens learned to expect decisive action rather than legal deliberation in moments of instability. Over time, imperium no longer required constant justification through civic legal forms. Crisis itself became sufficient authorization, allowing officials to interpret legality internally rather than submit their actions to independent review. Authority thus shifted from being procedurally grounded to being situationally defined.

By the time Augustus claimed to restore the Republic, the logic of emergency governance was deeply entrenched. The language of crisis had normalized administrative discretion and eroded expectations of restraint without requiring explicit legal rupture. Courts, magistracies, and legal rhetoric remained in place, preserving the appearance of continuity. Yet the balance between civic law and executive authority had shifted decisively. Crisis did not abolish Roman law. It transformed it, expanding imperium into a governing principle that privileged order, security, and survival over procedural accountability.

Augustus and the Administrative Turn

Augustus presented his rise to power as a restoration rather than a revolution. After decades of civil war, his political program emphasized stability, continuity, and the revival of traditional institutions that Romans associated with legitimate governance. Magistracies were preserved, senatorial forms endured, and the familiar language of Republican legality remained central to public discourse. Augustus repeatedly claimed that he held no extraordinary powers beyond those granted by law, precedent, and collective consent. These claims were carefully staged through public acts, inscriptions, and constitutional settlements that emphasized restraint rather than domination. Yet this rhetorical commitment to restoration masked a profound structural shift. Authority increasingly flowed not through civic legal process rooted in collective deliberation, but through administrative control exercised in the emperor’s name, insulated from the procedural constraints that had once defined Republican legality.

The genius of Augustan governance lay in its ability to preserve legal forms while redirecting their function. Courts continued to operate, assemblies met, and jurists elaborated legal doctrine with renewed vigor. At the same time, decisive power migrated toward the emperor’s household, advisors, and delegated officials. Augustus accumulated imperium and auctoritas in ways that allowed him to intervene across legal domains without formally abolishing Republican constraints. What emerged was not a lawless regime, but a system in which law operated alongside, and often subordinate to, executive discretion.

Central to this transformation was the expansion of administrative authority justified by necessity, efficiency, and the promise of restored order. Augustus consistently framed his interventions as pragmatic responses to disorder, corruption, and moral decline rather than as assertions of personal sovereignty. By casting administrative action as corrective rather than coercive, he normalized the idea that executive decisions could precede or bypass formal legal process without undermining legitimacy. Over time, administrative mandates came to be treated as inherently lawful because they emanated from the emperor’s responsibility to safeguard the state. Decisions increasingly originated in imperial directives rather than civic deliberation, particularly in matters touching security, loyalty, and public morality. This subtle shift redefined legality itself, transforming it from a procedural guarantee into an expression of administrative judgment.

Delegation played a crucial role in sustaining this new model of governance. Augustus relied on prefects, legates, and other appointed officials who exercised authority directly on his behalf. These agents operated within broad mandates that prioritized outcomes over process. Accountability flowed upward through administrative hierarchies rather than outward to civic institutions. While this system enhanced efficiency and centralized control, it also weakened traditional mechanisms of review and appeal. Legal protection became increasingly contingent on imperial favor and administrative interpretation rather than guaranteed by established procedural rights.

The effects of this administrative turn were especially visible in the regulation of social order, where law and governance merged most clearly. Augustan legislation on marriage, morality, citizenship, taxation, and public conduct expanded the state’s presence within everyday life. Enforcement often relied less on formal prosecution than on surveillance, reporting, and discretionary intervention by officials empowered to act in the emperor’s name. These measures reshaped the boundary between public authority and private conduct, allowing administrative oversight to penetrate areas once governed by custom and civic restraint. Augustus did not abolish civic law, but he repositioned it within a broader framework of executive management, where compliance and order mattered more than procedural contestation. Law became an instrument for shaping behavior as much as for adjudicating disputes.

By the end of Augustus’ reign, the transformation was complete in substance if not in name. Rome remained a legalistic society, deeply invested in precedent, procedure, and juristic reasoning. Yet the locus of authority had shifted decisively. Administrative power now structured the relationship between state and citizen, redefining legality through executive interpretation and delegated enforcement. Augustus thus inaugurated a political order in which continuity masked innovation, and where the preservation of legal form concealed the ascendancy of administrative rule over civic law.

Intrusion into the Household: From Legal Exception to Routine Practice

Under the early Empire, the Roman household gradually ceased to function as a presumptively inviolable space and became instead a site of administrative concern. What had once required extraordinary justification increasingly fell within the normal scope of imperial oversight. Officials entered homes to conduct censuses, enforce taxation, investigate loyalty, or carry out moral regulation, often without the formal procedures that had characterized Republican intrusions. These actions were rarely framed as violations of law. Rather, they were presented as necessary extensions of administrative responsibility, justified by the emperor’s duty to preserve order and stability.

This shift did not occur through explicit legal abolition of household protections. Instead, it unfolded through reinterpretation, accumulation of precedent, and everyday practice. Administrative authority expanded incrementally, treating the household less as a protected civic unit and more as a functional component of governance. Imperial agents acted under broad mandates that emphasized effectiveness and compliance over procedural restraint. Judicial warrants or independent authorization became less central than administrative instruction. As a result, the evaluation of legality moved inward. Decisions were judged lawful because they aligned with imperial purpose, not because they had passed through an external civic process capable of limiting power.

Repetition transformed exception into routine and habituated subjects to intrusion as an ordinary feature of governance. The more frequently officials crossed the threshold of private space in the name of security, taxation, or moral discipline, the less visible the legal rupture appeared. Resistance became difficult precisely because the language of law remained intact. Subjects were not told that protections had been abolished. They were told that intervention was lawful. Appeals, when available, flowed upward through administrative hierarchies rather than outward to independent courts, reinforcing a system in which enforcement agencies effectively defined the scope of legality themselves. What had once been a boundary policed by procedure became a zone regulated by discretion.

The result was a quiet but consequential redefinition of the relationship between household and state. Domestic sanctuary did not disappear, but it became conditional, dependent on administrative judgment rather than guaranteed by civic law. Rome demonstrates how power can penetrate private life without formally renouncing legality, until intrusion becomes unremarkable and protection exists only at the pleasure of authority.

Legality Redefined: When Power Becomes Its Own Justification

By the early Imperial period, Roman law had not disappeared, but its function had shifted in decisive ways. Legal language and institutions remained visible, preserving the appearance of continuity with Republican norms. Yet judgment was no longer anchored primarily in independent civic process. Increasingly, legality depended on administrative interpretation exercised by those who held power.

This transformation altered the relationship between law and authority at a structural level. In the Republic, law claimed an external position, at least in principle, standing apart from magistrates as a procedural standard against which power could be measured. Under the Empire, law became an internal language of governance. Officials did not abandon legality; they absorbed it. Administrative action acquired legal force by virtue of its origin within the imperial system itself. Mandates, directives, and delegated authority were treated as lawful not because they had passed through independent review, but because they emanated from recognized power. Legality thus ceased to function primarily as a constraint and instead became an attribute of authority.

As this internalized legality expanded, the distinction between lawful action and command steadily eroded. Enforcement agencies increasingly interpreted legality on their own authority, leaving little room for meaningful external review. Appeals, when permitted, moved upward through administrative hierarchies rather than outward to institutions capable of restraining power. This structure prioritized efficiency, coordination, and predictability, but it hollowed out accountability. Subjects encountered their legal framework less as a forum for contestation and more as a framework of compliance, justified through administrative reasoning after the fact. The question was no longer whether an action was lawful in procedural terms, but whether it could be rationalized as necessary within the system itself.

Crucially, this redefinition of legality did not provoke sustained resistance because it preserved familiar forms. Courts continued to operate, jurists continued to write, and legal education continued to flourish. These institutions created the impression that law remained intact as an independent force. Yet their function had subtly changed. Increasingly, they explained and systematized decisions already made through executive discretion rather than determining outcomes through adversarial process. Law became retrospective and justificatory, supplying coherence to authority rather than limiting it in advance.

Rome offers a powerful illustration of how legality can endure even as its substance is transformed. When power becomes its own justification, law does not vanish; it is reoriented. It survives as administrative reason, stabilizing authority through continuity of language and form. The danger of such a system lies precisely in its durability. By preserving legality’s outward appearance, it renders the erosion of restraint gradual, normalized, and difficult to perceive. Legality remains, but it no longer stands apart from power. It speaks in power’s voice, and in doing so, secures obedience without the need for overt rupture.

Ancient Rome and Modern Administrative Enforcement

Rome’s transformation from civic law to administrative legality offers more than a historical case study. It provides a structural pattern for understanding how modern states expand enforcement power without formally abandoning legal norms. In both contexts, authority does not announce the end of law. Instead, it redefines legality internally, shifting judgment from independent civic institutions to executive agencies tasked with maintaining order. The result is a system in which enforcement precedes adjudication, and legality is determined by administrative mandate rather than judicial review.

Modern administrative enforcement mirrors this Roman trajectory most clearly in the use of executive authorization to bypass traditional legal safeguards. Agencies empowered to act in the name of security, efficiency, or necessity increasingly rely on internally generated warrants, directives, or administrative approvals rather than independent judicial oversight. These mechanisms are framed as lawful instruments of governance, not as exceptional departures from constitutional norms. As in imperial Rome, the justification rests on delegated authority and institutional competence rather than on adversarial review. The language of legality remains intact, but the procedural substance associated with civic law is displaced. What changes is not the existence of law, but the locus at which legality is defined and enforced.

The structural similarity lies in the relocation of judgment from external review to internal discretion. In both Rome and modern administrative systems, enforcement bodies increasingly determine for themselves when intrusion is justified, what evidentiary standards apply, and how compliance is assessed. Oversight mechanisms, when present, often operate within the same administrative hierarchy, emphasizing managerial accountability over independent restraint. This inward turn enhances speed, coordination, and predictability, particularly in large and complex states. Yet it also collapses the distinction between law as a limit and law as an instrument. Legality becomes whatever the enforcement apparatus recognizes as valid, rendering procedural protection contingent rather than guaranteed.

Rome’s experience demonstrates that such systems do not require authoritarian rupture to succeed. They rely instead on continuity, normalization, and the quiet accumulation of precedent. Civic law persists in form, preserving the appearance of restraint and legitimacy, while its function is altered as administrative discretion becomes the primary engine of governance. The lesson is not that modern states are Rome reborn, but that Rome reveals how legal systems can be transformed from within. When enforcement agencies define legality internally, law survives, but restraint becomes conditional, dependent on power rather than secured against it.

Conclusion: The Quiet Death of Civic Law

Rome’s experience demonstrates that civic law does not perish through dramatic overthrow or explicit repeal. It erodes through reinterpretation, delegation, and normalization. Legal forms endure, institutions persist, and the language of legality remains intact, even as the function of law shifts away from constraint and toward administration. Power does not announce its independence from law. Instead, it absorbs law into itself, redefining legality as whatever authority determines to be necessary for order.

This transformation succeeds precisely because it preserves continuity. Romans did not wake up to find law abolished or rights openly revoked. Courts still convened, jurists still reasoned, and officials continued to speak in the idiom of tradition and restoration. Yet the practical meaning of legality had altered in subtle but decisive ways. Procedural guarantees increasingly yielded to discretionary judgment, and formal review gave way to executive mandate. What once required public justification through civic process could now be resolved administratively, behind closed doors, and without independent scrutiny. Civic law survived as structure, vocabulary, and ritual, but it no longer functioned as a reliable check on power. Its authority rested less on procedure than on alignment with the priorities of governance.

The fate of the Roman household captures this shift with particular clarity. Once treated as a legally and symbolically protected space, the domus became subject to routine administrative intrusion justified by loyalty, security, taxation, or moral regulation. The threshold of the home, long associated with restraint and autonomy, gradually lost its juridical force. This change did not occur because lawmakers openly repudiated domestic protections, but because enforcement practices redefined their meaning. Law was not removed from the household; it was repurposed within it. Protection became conditional, contingent on compliance and administrative interpretation rather than guaranteed by civic right. In this way, the household became a microcosm of Rome’s broader legal transformation.

Rome’s warning lies not in tyranny, but in normalization. The quiet death of civic law occurs when legality remains visible but restraint does not. When enforcement agencies define legality internally, law survives in name while its capacity to oppose power dissolves. Rome reminds us that the most enduring transformations of law are those that preserve its appearance. Continuity becomes the mechanism through which constraint is hollowed out, and legality speaks with the voice of authority alone.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- —-. Law, Language, and Empire in the Roman Tradition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

- Crook, John A. Law and Life of Rome, 90 B.C.–A.D. 212. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967.

- Flower, Harriet I. Roman Republics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Gardner, Jane F. Family and Familia in Roman Law and Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Garnsey, Peter. Thinking about Property: From Antiquity to the Age of Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Harries, Jill. Law and Crime in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Levy, Ernst. “Statute and Judge in Roman Criminal Law.” Washington Law Review 13:4 (1938): 291-304.

- Lintott, Andrew. The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- —-. Violence in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Malsbary, Gerald. “Pietas and the Origins of Western Culture.” Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture 4:2 (2001): 93-116.

- Metzger, Ernest. “An Outline of Roman Civil Procedure.” Roman Legal Tradition 9 (2013): 1-30.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC–AD 337). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Riggsby, Andrew M. Roman Law and the Legal World of the Romans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Smith, Hailey. “Cultural Imperialism in the Roman Empire: a Give and Take Relationship between Imperial Rome and Provincial/External Cultures.” Venture: The University of Mississippi Undergraduate Research Journal 6:11 (2024): 126-133.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Augustan Rome. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1921.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.28.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.