From medieval England onward, the requirement of independent authorization emerged as a response to power’s tendency to justify itself through necessity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Castle and the Crown

Medieval English law developed one of its most enduring principles around the protection of the home. The oft-cited maxim that every man’s house is his castle was not a metaphorical flourish but a concrete legal claim about the limits of authority. The household marked a boundary where private rights, property, and personal security converged. Crossing that threshold lawfully required justification, and increasingly, authorization grounded in judicial process. The home thus became a constitutional frontier long before the emergence of modern constitutionalism.

This protection did not arise from abstract theory but from recurring, practical conflict. Medieval governance relied heavily on local enforcement by sheriffs and royal officers, whose responsibilities included tax collection, debt enforcement, arrest, and the suppression of disorder. These agents frequently acted under the king’s command, invoking prerogative authority to enter homes without judicial warrants. Such practices exposed a deep fault line within English law: whether royal command itself constituted legality or whether legality required independent judicial authorization. The struggle over entry therefore became a recurring test of institutional authority. Each intrusion raised the same unresolved question, forcing courts, communities, and officials to confront whether law functioned as a restraint on power or merely as its rationalization.

The crown defended prerogative as a practical necessity of rule. Kings asserted the need for swift action in the name of order, loyalty, and security, particularly when judicial processes appeared slow or resistant. Royal officers entered homes not as acknowledged lawbreakers, but as agents claiming lawful authority grounded in sovereignty rather than adjudication. Prerogative thus operated as a parallel legal logic, one that did not deny law outright but subordinated it to executive judgment.

The importance of this conflict lies in its persistence rather than its resolution. Medieval England never decisively settled who possessed the final authority to authorize entry into the home. Instead, the struggle became institutionalized, recurring across reigns and crises. Courts repeatedly articulated limits on royal power, while the crown repeatedly tested those limits through practice. Over time, this tension shaped the development of warrants, judicial oversight, and the expectation that lawful entry required more than executive command. The household became the proving ground where English law learned, slowly and unevenly, to distinguish authority from legality, laying the groundwork for later constitutional protections without ever fully resolving the contest itself.

The Medieval English House as Legal Sanctuary

English common law developed a strong presumption that the home constituted a protected legal space, distinct from public authority and insulated from arbitrary intrusion. The household was not merely a site of residence or property, but a jurisdictional boundary where law recognized limits on coercive power. Entry into the home implicated questions of trespass, consent, and authority, making it one of the earliest arenas in which English law articulated restraint on governance. This presumption reflected a broader commitment to the idea that lawful power required justification when it crossed into private life. The threshold of the house thus became a legal test. To enter was to assert authority, and to assert authority was to invite legal scrutiny.

The legal protection of the home emerged gradually through doctrines of property and trespass rather than through explicit constitutional declaration. Common law treated unauthorized entry as a wrong even when committed by officials acting in the king’s name. This was not because royal authority was denied, but because its exercise was expected to conform to recognizable legal standards. The household thus functioned as a practical test of legality. If power could not justify its presence there, it exposed itself as force rather than law.

The sanctuary of the home was reinforced by social and moral expectations that linked property to personal security and communal order. Medieval jurists and judges understood that unchecked entry threatened not only individual households but confidence in law itself. The home was a space of livelihood, reputation, and familial authority, bound up with honor and social standing. Its violation could destabilize local relationships and provoke resistance far beyond the immediate intrusion. By protecting domestic space, common law asserted that order depended on visible restraint as much as on enforcement. Governance was legitimate only insofar as it demonstrated respect for boundaries that ordinary people recognized as meaningful.

Yet this protection was never absolute. Exceptions existed for hot pursuit, felony, or imminent danger, and these exceptions were often invoked expansively by royal officers. What distinguished the common law approach was not the absence of intrusion, but the insistence that intrusion be justified according to legal standards rather than mere command. The existence of exceptions sharpened the importance of the rule. Each claimed necessity forced courts to clarify whether an entry rested on law or prerogative.

The English house became both a symbolic and practical anchor for the development of legal restraint. It was within this space that common law refined the principle that authority required authorization, and that legality demanded reasons independent of executive will. The household stood at the intersection of private rights and public power, making it an ideal site for testing the reach of governance. Doctrines governing entry, trespass, and justification gradually accumulated into expectations that would later crystallize into formal warrant requirements. Long before written constitutions or rights declarations, English law treated the threshold of the home as the place where power was compelled to explain itself.

Royal Prerogative: Authority beyond Ordinary Law

Royal prerogative in medieval England operated as a parallel logic of authority rather than as an absence of law. It referred to those powers claimed by the crown as inherent to kingship, exercised in the name of governance, security, and necessity. Unlike common law, which emphasized precedent, adjudication, and local participation, prerogative derived its legitimacy from sovereignty itself. The king’s command carried legal force not because it had been tested in court, but because it was understood as an expression of the realm’s ultimate authority. This distinction placed prerogative in constant tension with ordinary law, especially when royal action crossed into spaces traditionally protected from arbitrary power.

The crown defended prerogative as indispensable to effective rule in a politically fragmented and often unstable society. Medieval kings argued that governance required flexibility, speed, and discretion, qualities judicial process could not always supply. Fiscal emergencies, military threats, rebellion, and disorder were invoked to justify immediate action without recourse to courts. Royal officers acted under direct command to collect taxes, seize goods, arrest suspects, or suppress resistance. Entry into private homes frequently followed from such directives, justified not by warrants issued through judicial procedure, but by the authority of the king’s mandate itself. These actions were framed as lawful precisely because they emanated from sovereignty. Prerogative thus functioned as an alternative source of legality, capable of overriding procedural restraint whenever necessity was asserted.

This prerogative logic did not deny the existence of common law protections, but it consistently subordinated them. Royal authority claimed the right to determine when ordinary law applied and when it must yield to higher necessity. Sheriffs and royal officers understood themselves as lawful actors even when their conduct conflicted with established common law norms. Their legitimacy rested not on judicial approval, but on obedience to command. This created a structural ambiguity within English governance. If legality flowed from command, then judicial oversight became contingent rather than authoritative, and restraint depended on the crown’s willingness to limit itself rather than on enforceable legal standards. The household, long treated as a protected space, became the most visible arena in which this ambiguity played out.

The significance of royal prerogative lies in its persistence rather than its coherence. Medieval England never fully resolved whether prerogative was bounded by law or stood above it. Instead, the tension endured as a permanent feature of governance, reappearing whenever enforcement demanded intrusion without judicial authorization. Courts responded incrementally, asserting limits in particular cases while leaving the broader claim of prerogative intact. Royal authority thus remained expansive but contested, operating beyond ordinary law while never entirely escaping its gravitational pull.

Warrantless Entry in Practice: Sheriffs, Searches, and Seizures

In practice, warrantless entry in medieval England was not an occasional deviation from legal norms but a recurring feature of royal administration. Sheriffs and other local officers served as the crown’s primary instruments of enforcement, responsible for executing commands that ranged from tax collection to arrest, seizure, and surveillance. Their authority derived less from judicial authorization than from royal writs, verbal orders, and customary expectations of obedience. This administrative reality meant that the legality of entry was often presumed rather than demonstrated. The boundary between lawful enforcement and coercive intrusion was therefore determined on the ground, shaped by power relations and urgency, rather than clarified in advance by courts.

Sheriffs occupied an ambiguous position within the legal order. They were officers of the law, sworn to uphold common law norms, yet they were also agents of royal power, expected to act decisively in the king’s interest. This dual role encouraged a practical prioritization of command over procedure. When instructed to recover debts, seize goods, or apprehend suspects, sheriffs frequently entered homes without warrants issued by judges. Such entries were justified as necessary acts of governance, carried out under color of authority rather than pursuant to adjudicated process.

Searches and seizures often accompanied these intrusions. Property was taken to satisfy unpaid obligations, enforce fines, or secure evidence of wrongdoing. The legal justification for such actions was rarely tested at the moment they occurred. Instead, legality was assumed by virtue of the officer’s role and the crown’s interest. Individuals whose homes were entered or goods seized faced a difficult choice. They could submit, relying on later remedies, or resist and risk being treated as defiant of royal authority. In either case, enforcement preceded review, placing the burden on subjects rather than on the state.

Judicial remedies existed in theory, particularly through actions for trespass or unlawful entry. In practice, however, these remedies were unevenly accessible and uncertain in outcome. Suing a royal officer required resources, persistence, and a willingness to challenge authority. Courts were often reluctant to interfere directly with the execution of royal commands, especially when officers claimed necessity or obedience. As a result, post hoc review functioned as a weak constraint, incapable of preventing intrusion even if it occasionally offered compensation afterward.

The repetition of warrantless entry normalized administrative intrusion into private space. What had once appeared exceptional gradually became routine, especially during periods of fiscal pressure, war, or political instability. Local communities learned to expect that royal officers could cross domestic thresholds without prior judicial approval. This habituation reshaped everyday assumptions about law and authority. The home remained symbolically protected in doctrine, but its practical defense increasingly depended on the restraint of officials rather than on enforceable procedural barriers. Protection existed in theory, while vulnerability defined experience.

The cumulative effect of these practices was a subtle but consequential redefinition of legality itself. Enforcement came to be understood as presumptively lawful when carried out by authorized officers, regardless of whether judicial warrants were obtained. Courts retained the ability to articulate limits after the fact, but they rarely prevented intrusion before it occurred. Warrantless entry thus became a structural feature of medieval governance rather than a legal anomaly. Through routine practice, prerogative authority reshaped the relationship between law, power, and the household, demonstrating how legality could be preserved in form while eroded in function.

Judicial Resistance and the Growth of Legal Constraint

Despite the persistence of prerogative practice, medieval English courts did not simply acquiesce to warrantless intrusion. Over time, judges articulated an increasingly firm expectation that royal authority, when exercised through officers, remained subject to legal standards. This resistance was rarely dramatic or confrontational. Courts did not deny the existence of prerogative, nor did they claim the power to abolish it outright. Instead, they worked incrementally, case by case, asserting the judiciary’s role as an arbiter of legality even in matters touching royal authority. Judicial resistance thus emerged not as open defiance, but as a disciplined insistence that power could be questioned, justified, and evaluated within a legal framework.

One of the principal tools of this resistance was the action for trespass. Individuals whose homes were entered without lawful justification increasingly sought redress through the courts, framing intrusion as a legal wrong regardless of the officer’s claim to royal authority. Judges proved willing, at least in some cases, to entertain these claims and to distinguish between lawful enforcement and unlawful excess. The very availability of trespass actions signaled an important principle: obedience to command did not automatically confer legality. Officers could be required to justify their conduct in legal terms, and failure to do so exposed them to liability.

This judicial posture placed growing pressure on the crown’s agents and gradually reshaped enforcement behavior. Sheriffs and royal officers became more attentive to the need for legal justification, even when acting under direct command. Courts increasingly emphasized the importance of warrants and formal authorization, not as procedural technicalities but as substantive safeguards distinguishing lawful authority from arbitrary force. The expectation that entry required judicial sanction began to solidify, particularly in cases involving the home. These developments did not eliminate prerogative intrusion, but they constrained it by introducing legal risk and accountability into practices that had previously relied on command alone.

The growth of legal constraint was therefore cumulative rather than decisive. Courts asserted their authority without directly challenging sovereignty, carving out spaces where law could reassert itself against administrative overreach. This process was uneven and often contested, but it laid crucial groundwork for later constitutional developments. By insisting that royal agents answer to law, medieval judges helped establish the principle that enforcement must be justified independently of executive will. Judicial resistance did not defeat prerogative, but it forced power to operate within an increasingly articulated legal framework, transforming the household into a lasting site of legal accountability.

Conflict without Resolution: The Crown versus the Courts

The tension between royal prerogative and judicial authority in medieval England never reached a definitive settlement. Instead of resolution, the legal system absorbed conflict as a recurring condition of governance. Kings asserted prerogative when necessity demanded speed, secrecy, or decisive action, while courts reasserted common law principles when opportunity allowed. This cyclical struggle did not weaken the system so much as it stabilized it through managed ambiguity. Authority and legality coexisted in tension, each shaping the other without eliminating the rival claim, producing a legal culture accustomed to unresolved boundaries rather than fixed constitutional lines.

For the crown, unresolved conflict preserved essential flexibility. By refusing to concede that judicial authorization was always required for entry, the king retained the capacity to act swiftly in moments framed as urgent or dangerous. Royal officers continued to rely on command rather than warrant, confident that necessity, loyalty, or service to the realm could later be invoked as justification. Even when courts ruled against individual officers, such judgments were treated as correctable excesses rather than as binding limits on prerogative itself. The crown could retreat in specific cases without surrendering its broader claim, allowing royal authority to absorb legal criticism while continuing to operate largely on its own terms.

For the courts, the absence of final resolution created space for gradual assertion without provoking open constitutional confrontation. Judges avoided framing their decisions as challenges to sovereignty. Instead, they narrowed prerogative through interpretation, procedural expectation, and the imposition of liability. Trespass actions, evidentiary scrutiny, and demands for justification slowly expanded judicial oversight over enforcement practices. Each decision reinforced the idea that royal agents were subject to law, even if the crown remained theoretically supreme. Over time, this accumulation of rulings reshaped expectations about lawful entry, not by abolishing prerogative, but by forcing it to coexist uneasily with judicial standards.

This unresolved conflict shaped the lived experience of law for medieval subjects. Legality appeared contingent, dependent on circumstance, authority, and timing. An entry might be justified by prerogative in one moment and condemned as unlawful trespass in another. Such uncertainty favored power, but it also preserved avenues for resistance. Subjects learned to invoke common law language, to seek redress after intrusion, and to treat the courts as potential allies even when enforcement proceeded under royal command. The household remained a contested site where legal principle and executive necessity collided repeatedly, making domestic space a focal point of constitutional tension.

The endurance of this conflict is its most significant legacy. Medieval England did not resolve the struggle between crown and courts. It institutionalized it as a permanent feature of governance. By allowing prerogative and common law to coexist without a fixed hierarchy, the legal system created conditions under which restraint could be argued, expanded, and defended incrementally. This unresolved tension would resurface with greater intensity in the early modern period, shaping debates over warrants, parliamentary authority, and constitutional limits. What medieval law bequeathed was not clarity, but a durable framework in which the meaning of legality remained contested and therefore politically consequential.

From Medieval Conflict to Constitutional Principle

The unresolved struggle between royal prerogative and common law restraint did not dissipate with the close of the medieval period. Instead, it hardened into doctrine. What had been contested in practice became articulated in principle as English jurists, parliamentarians, and judges sought to clarify the relationship between authority and legality. The centuries-long conflict over warrantless entry supplied both the vocabulary and the institutional memory through which later constitutional limits were framed. Medieval ambiguity thus became the raw material of early modern constitutionalism.

One of the most significant developments was the growing insistence that lawful authority required prior authorization rather than post hoc justification. Courts increasingly emphasized that intrusion into the home demanded more than sovereign intent or administrative convenience. This insistence emerged through repeated confrontation with abuse, not through abstract theorizing. Each contested entry sharpened the distinction between necessity asserted after the fact and legality established in advance. The household, long treated as a contested space, became the anchor for a procedural principle: power must explain itself before it acts. The warrant, as it gradually took clearer institutional form, embodied this shift by relocating judgment from the discretion of officers to an external authority capable of restraint.

Parliament played a crucial role in transforming medieval tension into constitutional assertion. As conflicts between crown and courts intensified, legislative interventions increasingly reframed prerogative as a systemic problem rather than an episodic excess. Parliamentary grievances catalogued familiar injuries: entry without warrant, seizure without adjudication, and enforcement justified by command alone. These complaints drew directly on medieval experience, invoking the language of common law protection and domestic inviolability that had long circulated in local courts. By elevating these disputes to the national stage, Parliament converted localized resistance into constitutional argument. The struggle over entry thus migrated from case law to statute, from judicial remedy to political principle.

The Petition of Right marked a pivotal moment in this transition. It did not invent new protections, nor did it abolish prerogative. Instead, it codified a long-standing objection to the idea that royal command could substitute for law. By insisting that the king could not override legal process through mere assertion of necessity, the Petition distilled centuries of judicial resistance into constitutional form. Although enforcement remained uneven and contested, the claim itself represented a decisive shift. Prerogative could no longer plausibly present itself as an independent source of legality without encountering institutional opposition grounded in precedent rather than innovation.

Sir Edward Coke’s jurisprudence further transformed medieval conflict into constitutional doctrine. Drawing explicitly on common law tradition, Coke articulated the principle that even the sovereign was subject to law. His defense of the home as a protected legal space echoed medieval trespass doctrine while projecting it into a broader constitutional framework. The maxim that a man’s house is his castle thus evolved from a practical rule governing entry into a symbolic boundary of liberty. Domestic security became inseparable from the rule of law itself, linking private space to public restraint.

These developments crossed the Atlantic with English settlers and profoundly shaped American constitutional thought. Colonial resistance to general warrants and writs of assistance did not emerge in a vacuum. It reflected an inherited legal memory in which executive intrusion had long been contested. The same medieval concern reappeared in colonial argument: whether power could enter the home without independent authorization. The Fourth Amendment crystallized this tradition by constitutionalizing the warrant requirement as a condition of legitimacy. In this sense, American protections against unreasonable searches represent not a break with the past, but the culmination of a struggle that began centuries earlier, when English law first treated the threshold of the house as the place where authority must justify itself.

Medieval Prerogative and Modern Administrative Entry

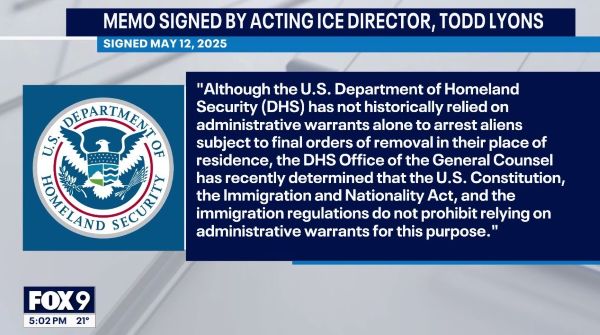

The logic that underpinned medieval royal prerogative did not disappear with the rise of constitutional government. It was transformed, professionalized, and relocated within administrative structures. In both medieval England and modern states, the central claim remains strikingly similar: executive authority asserts the power to act first and justify later, particularly in the name of order, security, efficiency, or necessity. What changes over time is not the structure of the argument, but its institutional clothing. Where medieval kings relied on command conveyed through sheriffs and writs, modern administrations rely on internal memoranda, delegated authority, and agency interpretation to authorize entry without independent judicial review. The form is bureaucratic rather than personal, but the logic of prerogative endures.

Modern administrative entry mirrors medieval prerogative most clearly in its reliance on internally generated authorization. Enforcement agencies empowered to regulate borders, collect revenue, or police compliance often assert that executive instruction alone suffices to justify intrusion. Judicial warrants are reframed as optional, impractical, or incompatible with effective governance. As in medieval England, the claim is not that law is irrelevant, but that legality is satisfied by executive determination itself. Authority thus defines the scope of its own restraint, collapsing the distinction between enforcement and adjudication that common law historically worked to preserve.

The structural danger of this logic lies in its normalization. Medieval prerogative did not announce itself as tyranny. It operated through routine practice, gradually reshaping expectations about lawful entry. Modern administrative systems function in much the same way. When agencies regularly enter homes based on internal authorization, the extraordinary becomes ordinary. Review mechanisms, when available, tend to be retrospective and internal, offering rationalization rather than restraint. Law remains visible, procedures remain codified, and accountability appears intact, even as the capacity of courts to intervene in advance diminishes.

The medieval experience demonstrates why this pattern matters so deeply. English law did not preserve the sanctity of the home by trusting executive self-restraint or benevolent intent. It preserved it by insisting, over centuries of conflict, that independent authorization was a condition of legitimacy. Warrants emerged not as technical devices, but as constitutional boundaries separating lawful authority from mere command. When modern administrative systems bypass that requirement, they revive the core logic of prerogative stripped of its historical struggle and hard-won limits. The lesson is not that modern governance reenacts medieval monarchy, but that the same foundational question persists. Whenever executive authorization replaces judicial review, the issue is unchanged: does law restrain power, or does power quietly redefine law from within?

Conclusion: Why Warrants Are Never Technical

The long struggle over entry into the home reveals that warrants have never been mere procedural formalities. From medieval England onward, the requirement of independent authorization emerged as a response to power’s tendency to justify itself through necessity. Warrants did not arise to improve efficiency or administrative clarity. They arose to draw a line. That line separated command from legality, discretion from justification, and authority from force. To treat warrants as technical devices is to misunderstand their historical function as constitutional boundaries forged in conflict rather than convenience.

Medieval experience demonstrates that power rarely abolishes law outright. Instead, it reinterprets law internally, claiming legality through prerogative, delegation, or administrative logic. Royal officers entered homes not because law had vanished, but because legality had been relocated to command. Courts responded not by denying authority, but by insisting that authority required external authorization to be lawful. The warrant thus emerged as a mechanism for forcing power to submit to judgment before acting, rather than explaining itself afterward. This insistence reshaped expectations about legitimacy. It asserted that legality could not be satisfied by obedience alone and that enforcement required prior justification grounded in law rather than necessity. Over time, this principle became central to the idea that restraint must precede action, not follow it.

The persistence of this struggle explains why warrants remain politically and constitutionally charged. When executive actors claim that internal authorization suffices for entry, they revive the core logic of prerogative. The argument is familiar across centuries: urgency, efficiency, and security demand action without delay. History shows that such claims are not new, nor are they neutral. They represent an effort to shift legality from independent review to executive determination, from adjudication to administration. In every era, this move has preserved the language of law while weakening its restraining force, allowing power to operate with fewer external checks while insisting that legality remains intact.

Warrants matter not because they perfect procedure, but because they preserve a relationship between law and power that would otherwise erode quietly. They insist that enforcement must answer to judgment rather than command, to authorization rather than assertion. Medieval England teaches that the erosion of this principle is gradual, normalized, and often invisible until it is deeply entrenched. The lesson is neither nostalgic nor antiquarian. It is structural and enduring. Whenever warrants are dismissed as technicalities, the underlying question returns with full force and historical clarity: does law restrain power, or does power decide for itself what the law permits?

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Baker, J. H. An Introduction to English Legal History. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Coke, Edward. The Institutes of the Laws of England. London, 1628–1644.

- Harding, Alan. Medieval Law and the Foundations of the State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Holdsworth, William S. A History of English Law. Vol. 3. London: Methuen, 1923.

- Jenks, Edward. “The Prerogative Writs in English Law.” Yale Law Journal XXXII:6 (1923): 523-534.

- Kowaleski, Maryanne and P. J. P. Goldberg (eds). Medieval Domesticity: Home, Housing and Household in Medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Langbein, John H. The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Marin, Marilena. “Legal Particularities in the Medieval Era.” Research Association for Interdisciplinary Studies (RAIS) Conference Proceedings (2023): 77-83.

- McCune, Pat. “Justice, Mercy, and Late Medieval Governance.” Michigan Law Review 89:6 (1991): 1661-1678.

- McIlwain, Charles Howard. The High Court of Parliament and Its Supremacy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1910.

- Musson, Anthony. Public Order and Law Enforcement: The Local Administration of Criminal Justice, 1294–1350. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1996.

- Plucknett, Theodore F. T. A Concise History of the Common Law. 5th ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1956.

- Pollock, Frederick, and Frederic William Maitland. The History of English Law before the Time of Edward I. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898.

- Pound, Roscoe. “Legal Profession in the Middle Ages.” Notre Dame Law Review 19:3 (1944): 229-244.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.28.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.