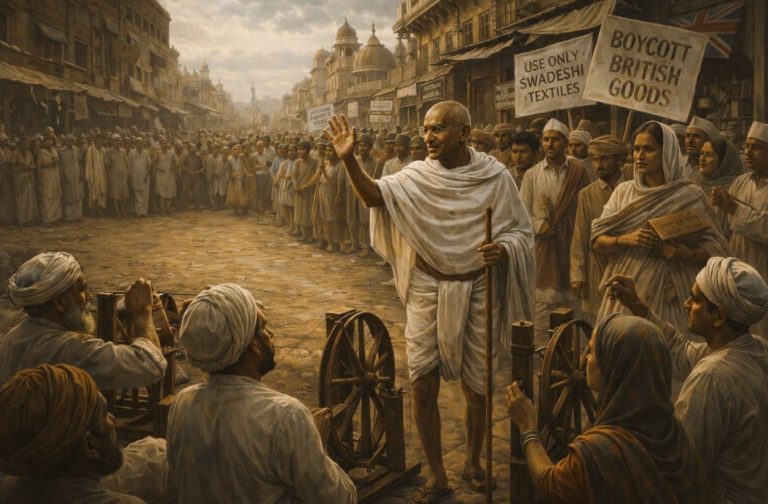

Economic noncooperation succeeded precisely because it avoided the language and posture of revolt while striking at the material foundations of rule.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power without Provision

Medieval political authority has often been described in the language of force: castles, knights, sieges, and the spectacle of armed domination. Yet this emphasis obscures a more fragile reality. Lordship in medieval Europe functioned as an economic system before it was a military one. Rulers extracted rents, tolls, labor obligations, and market dues through continuous interaction with towns whose cooperation made those flows possible. Authority was not exercised in isolated moments of violence but sustained through daily participation in exchange. When that participation faltered, power itself weakened.

Urban communities gradually recognized this structural dependency and learned to exploit it with increasing sophistication. Rather than confronting rulers through open rebellion, which invited devastating retaliation and long memory, towns developed methods of resistance that operated beneath the threshold of violence. Shops closed in coordinated fashion, guild labor was suspended, market days went quiet, and tax payments stalled without dramatic proclamation. Supply networks were redirected away from seigneurial centers, often under the cover of ordinary commercial decisions. These actions were difficult to criminalize and even harder to reverse by force. Lords could compel obedience from individuals, but they could not easily coerce a city into producing prosperity on command. Economic silence, maintained over time, proved more destabilizing than riots or barricades, because it attacked the fiscal foundations of rule rather than its symbols.

This strategy challenges rebellion-centered narratives of medieval resistance and demands a reconsideration of how political pressure operated in premodern societies. Traditional historiography has privileged moments of uprising because they are dramatic, visible, and well recorded in narrative sources. Yet such revolts often ended in repression, loss of life, and the reinforcement of seigneurial authority. By contrast, sustained economic noncooperation frequently yielded tangible results. Charters of privilege, municipal liberties, exemptions from tolls, and negotiated limits on lordly interference were commonly the products of prolonged refusal rather than military confrontation. Towns that avoided overt defiance preserved their institutions while quietly reshaping the terms of governance. Resistance, in this sense, was not an explosion but a durable condition, maintained through collective discipline and shared economic interest.

What follows argues that medieval towns reshaped political power by exploiting its dependence on exchange. Control over armed force mattered, but it proved insufficient when economic systems ceased to function. Lords learned, repeatedly and reluctantly, that authority without provision was unsustainable. When money, goods, and labor stopped moving upward, rulers were compelled to listen. This dynamic, visible across Europe from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, reveals a foundational truth of governance that extends well beyond the medieval world.

Feudal Authority as an Economic System

Feudal authority in medieval Europe rested on continuous economic extraction rather than episodic domination. Lords depended on rents from urban property, tolls on trade routes, fees collected at markets, and customary payments tied to commercial activity. These revenues were not optional supplements to power. They were the material foundation that sustained households, retainers, judicial systems, and military readiness. Without predictable income, lordship could not function as a stable institution. Political authority operated through routine economic participation far more often than through coercive display.

This dependency placed towns in a structurally ambiguous position. On paper, urban communities existed under the jurisdiction of kings, bishops, or territorial lords, bound by oaths, charters, or customary subordination. In practice, those same authorities relied on towns to generate cash, administer taxation, manage supply chains, and maintain local order. Markets did not flourish because rulers commanded them to do so, but because merchants, artisans, and guilds chose to participate under conditions they found tolerable. The smooth functioning of urban economies depended on trust, custom, and voluntary coordination, all of which lay beyond the direct reach of armed force. Excessive interference could fracture these relationships, driving merchants elsewhere or suppressing production altogether. A lord could seize goods or punish individuals, but such actions disrupted the very systems that produced revenue in the first place, transforming authority into an engine of scarcity rather than extraction.

Feudal extraction also required administrative cooperation that was neither automatic nor purely hierarchical. Town officials collected taxes, enforced tolls, maintained records, regulated markets, and transmitted funds upward through channels that depended on local compliance. This bureaucratic labor was often performed by urban elites whose loyalty was conditional rather than absolute and whose interests were tied to commercial stability rather than princely ambition. Unlike rural peasants bound by land tenure, townspeople possessed mobility, capital, and collective organization, allowing them to negotiate, delay, or obstruct administrative demands. Their participation in governance blurred the boundary between ruler and ruled, producing a hybrid system in which authority was exercised through collaboration as much as command. Lordship operated as a negotiated arrangement embedded in economic practice, not as a purely coercive hierarchy.

The limits of coercion became especially visible when rulers attempted to intensify extraction. Sudden increases in tolls, arbitrary fines, or interference in guild regulation frequently provoked resistance not through violence but through withdrawal. Commerce slowed, payments lagged, and administrative efficiency deteriorated. Military solutions proved ill suited to these problems. Occupying a town or punishing its leaders often resulted in long-term economic decline, reducing the very revenues rulers sought to secure. Force could compel obedience temporarily, but it could not restore confidence or productivity.

Understanding feudal authority as an economic system reveals why noncooperation was such an effective political tool. Lords commanded soldiers, but towns controlled circulation: goods, labor, credit, and information moved through urban networks that could not be sustained through fear alone. Markets required participation, guilds required consent, and fiscal systems required trust. When urban communities disrupted these processes, they exposed a fundamental weakness in feudal power. Authority depended on participation, and participation could be withheld without open rebellion. This imbalance transformed economic refusal into leverage, allowing towns to extract concessions, secure privileges, and reshape legal relationships over time. What appeared as passive inaction was, in fact, an active form of political pressure embedded in the everyday mechanics of medieval exchange.

The Rise of Medieval Town Autonomy

The emergence of autonomous medieval towns was not an accidental byproduct of economic growth but the result of deliberate institutional development. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, urban centers across Europe acquired legal identities that distinguished them from surrounding rural territories. Towns were increasingly recognized as corporate bodies capable of holding property, enforcing regulations, and negotiating collectively with external authorities. This legal personality allowed urban communities to act as unified economic and political actors rather than as aggregates of individuals subject to lordly discretion.

Guilds played a central role in this transformation. Craft and merchant guilds regulated labor, controlled entry into trades, stabilized prices, and coordinated production schedules. These organizations provided towns with an internal governance structure that could mobilize members quickly and enforce collective decisions. Because guild participation was tied to livelihood, compliance was strong. When guilds suspended work or restricted trade, the effects were immediate and difficult for external authorities to counter. Autonomy rested not only on charters or privileges but on the capacity to organize economic life internally.

Urban councils further expanded this capacity by institutionalizing decision-making and embedding it within durable political routines. Composed of merchants, master craftsmen, and local elites, councils oversaw taxation, market regulation, public works, and legal administration on a continuous basis rather than in response to crisis alone. Their authority derived less from formal delegation by rulers than from their practical control over urban systems and their ability to coordinate disparate interests within the town. Councils managed information, maintained records, negotiated collectively with external authorities, and disciplined internal dissent when necessary. This administrative competence made towns indispensable partners in governance while simultaneously reducing the feasibility of direct intervention by lords unfamiliar with local conditions or dependent on urban cooperation for revenue.

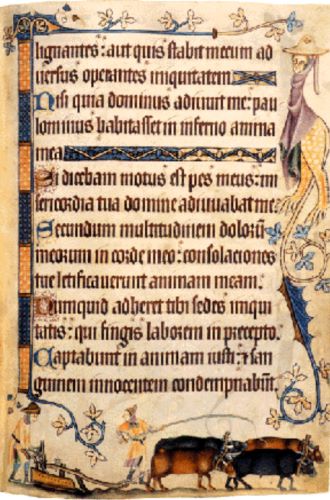

Literacy and record-keeping reinforced autonomy by transforming custom into documented practice. Town charters, account books, contracts, and correspondence created a paper infrastructure that stabilized rights and obligations. Written records allowed towns to assert continuity, defend privileges, and frame disputes in legal terms rather than through force. Documentation also facilitated coordination across guilds and neighborhoods, enabling collective action that was sustained and disciplined. Autonomy was grounded as much in clerks and archives as in walls and markets.

Economic diversification further strengthened urban independence by reducing vulnerability to single points of pressure. Towns that controlled multiple trades, regional markets, and long-distance connections were less exposed to coercion applied at any one node. Merchants could reroute supply chains, artisans could shift production toward alternative markets, and councils could delay payments without immediate collapse. Credit networks and mutual aid within towns helped cushion temporary losses, allowing communities to sustain noncooperation longer than individual actors could. This flexibility made economic pressure an effective negotiating tool, since the costs to rulers accumulated steadily while towns retained room to maneuver.

By the late medieval period, urban autonomy had become a structural feature of European political life rather than an exception carved out through repeated struggle. Towns were no longer passive recipients of authority but active participants in shaping it, capable of coordinating resistance without abandoning legal forms. Their capacity for collective organization, administrative competence, and economic coordination allowed them to resist domination without rebellion and to extract concessions without warfare. Autonomy did not eliminate hierarchy, but it altered its operation by binding authority to negotiation and fiscal reality. This transformation set the stage for economic noncooperation to function not as a desperate tactic, but as a stable and recurring mode of political leverage.

Economic Noncooperation as Political Strategy

Economic noncooperation emerged in medieval towns as a deliberate political strategy shaped by structural awareness rather than ideological protest or spontaneous unrest. Urban communities did not need to articulate abstract theories of resistance to recognize where their leverage lay. They understood, through daily experience, that lordly power depended on predictable economic routines more than on episodic demonstrations of force. Markets, workshops, toll points, and administrative offices formed a dense web of activity that sustained authority through repetition and participation. By slowing, redirecting, or suspending those routines, towns could exert pressure without declaring opposition. Withholding participation rather than issuing demands allowed resistance to operate beneath the threshold of treason. Silence, delay, and inactivity proved safer and more effective than confrontation because they denied rulers the justification for violent reprisal while still undermining the material basis of rule.

This strategy relied on collective discipline and internal coordination. Guilds enforced work stoppages, councils delayed payments, and merchants altered trade routes in ways that appeared commercially rational rather than politically rebellious. Because these actions were framed as economic decisions, they resisted easy criminalization. Lords faced a dilemma. Punishing entire towns risked prolonged economic damage, while targeting individuals failed to restore lost revenue. Noncooperation exploited the mismatch between individual culpability and collective effect, making repression costly and negotiation attractive.

Unlike revolts, economic refusal unfolded. Its strength lay in duration rather than spectacle. Closed markets reduced toll income, disrupted supply chains, and strained lordly credit relationships. Administrative delays compounded fiscal uncertainty, weakening the capacity to fund military or judicial action. As losses accumulated, rulers were forced to weigh the costs of intransigence against the concessions required to restore cooperation. Noncooperation transformed political conflict into an accounting problem, one that favored towns with diversified economies and internal resilience.

Most importantly, economic noncooperation preserved institutional continuity and political legitimacy. Towns did not suspend governance or dissolve authority structures in the course of resistance. Councils continued to meet, records were maintained, courts functioned, and legal forms were carefully observed. This continuity mattered. It allowed urban communities to present their actions as temporary disruptions within an existing legal relationship rather than as outright rejection of authority. Resistance remained legible as negotiation rather than rebellion. As a result, concessions extracted through noncooperation were more likely to be formalized in charters, privileges, and exemptions that endured beyond the immediate conflict. By refusing to rebel, towns reshaped the terms of rule itself, embedding limits on authority within the ordinary operation of medieval political economy rather than outside it.

Case Studies in Urban Economic Pressure

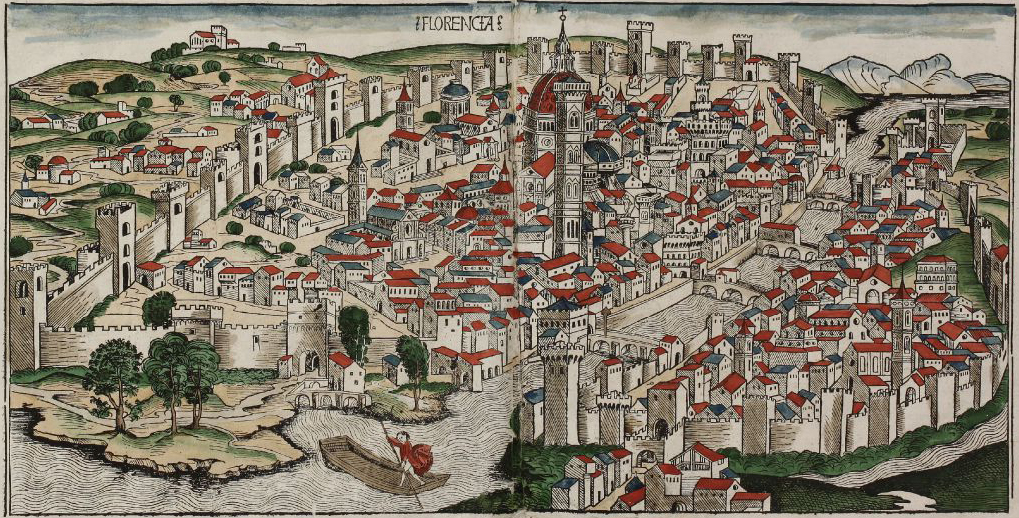

The effectiveness of economic noncooperation becomes most visible when examined across specific regional contexts, where similar strategies produced comparable outcomes despite differing political structures. In northern Italy, the rise of the communes demonstrated how urban economic pressure could force concessions from bishops and imperial representatives alike. Cities such as Milan, Florence, and Bologna did not rely solely on militias to assert autonomy. Instead, they disrupted toll collection, withheld customary payments, and redirected trade flows away from seigneurial intermediaries. Lords confronted with stalled revenues and declining credit were compelled to negotiate charters recognizing communal privileges, judicial autonomy, and limits on external interference.

In the commercial cities of Flanders, economic leverage proved equally decisive, though it operated through industrial specialization rather than communal political ideology. Towns such as Ghent, Bruges, and Ypres dominated textile production that depended on uninterrupted access to skilled labor, raw materials, and international markets. When counts attempted to impose new taxes, restrict municipal authority, or interfere in guild governance, urban communities responded by halting production and closing markets rather than by raising militias. Looms fell silent, workshops shuttered, and export flows slowed. These actions reverberated beyond city walls, affecting merchants, foreign buyers, and fiscal intermediaries whose cooperation rulers depended upon. Armed repression risked long-term damage to an economy that sustained comital authority itself, making compromise the more rational response. Flemish towns repeatedly secured concessions that preserved local control over taxation, labor regulation, and internal governance.

The Hanseatic League offers a further illustration of coordinated economic pressure operating across multiple jurisdictions. Rather than confronting territorial rulers militarily, Hanseatic cities employed collective embargoes, trade boycotts, and the withdrawal of shipping services as tools of negotiation. These measures exploited rulers’ dependence on customs revenue, port activity, and access to Baltic and North Sea commerce. When shipping lanes closed or merchants refused service, the effects rippled through princely finances, urban provisioning, and diplomatic relations. The League’s strength did not lie in force of arms, which remained limited, but in its ability to synchronize economic refusal across a network of cities. Local disruptions, when multiplied across dozens of ports, produced systemic pressure that few rulers could withstand for long.

In England, boroughs adapted similar tactics within a more centralized royal framework, demonstrating that economic noncooperation functioned even under comparatively strong monarchies. Urban communities delayed tax payments, resisted arbitrary tallages, and leveraged their indispensable role in royal finance, supply, and administration. Rather than rejecting royal authority outright, towns framed their actions as defenses of customary rights and economic practicality. Royal officials, dependent on urban credit, logistical support, and bureaucratic cooperation, often found confrontation counterproductive. Negotiation followed, resulting in confirmations of charters, limitations on interference in local markets, and recognition of municipal privileges. Economic noncooperation became a routine instrument of political bargaining rather than a crisis response.

A consistent pattern emerges. Urban communities that controlled key nodes of exchange were able to impose costs on rulers without resorting to open defiance. By targeting revenue streams, trade networks, and administrative cooperation, towns transformed political conflict into an economic problem. The success of these strategies depended less on ideological unity than on structural position. Where towns dominated commerce and could coordinate refusal, authority was forced to compromise. These case studies demonstrate that economic noncooperation was not an anomaly but a recurring and effective mode of political pressure in medieval Europe.

Why Lords Could Not Simply Use Force

The repeated resort to economic noncooperation by medieval towns exposes a central limitation of feudal power: coercion could punish, but it could not compel productivity. Military force was effective at suppressing visible defiance, dispersing crowds, or removing individual leaders, yet it was poorly suited to restoring the complex economic activity on which lordship depended. Markets did not reopen at sword point, artisans could not be forced to innovate under threat, and long-distance trade could not be sustained through intimidation alone. Commercial systems relied on trust, timing, and voluntary coordination across many actors, none of which could be generated through violence. In practice, force disrupted exchange more reliably than it restored it, making coercion a blunt instrument in conflicts rooted in fiscal dependency rather than territorial control.

The use of force also carried escalating costs. Maintaining garrisons, provisioning troops, and enforcing occupation drained resources that rulers often lacked without urban cooperation. A town placed under military pressure required constant oversight to prevent flight, sabotage, or passive resistance. Merchants relocated, capital moved elsewhere, and skilled labor quietly disappeared. Even successful repression frequently resulted in long-term economic decline, reducing tolls, taxes, and credit availability. Lords faced a paradox: the more aggressively they asserted control, the more they undermined the revenue streams that made control possible.

Administrative realities further constrained coercive solutions and revealed how deeply authority depended on cooperation. Lords relied on towns not only for wealth but for governance itself. Urban officials collected taxes, kept records, enforced regulations, organized provisioning, and mediated disputes. Removing, intimidating, or replacing these actors disrupted administrative continuity and degraded institutional memory. External officials rarely possessed the local knowledge required to manage complex urban systems, and imposed administrators often encountered deliberate inefficiency, procedural delay, or quiet noncompliance. Authority exercised without cooperation became increasingly hollow, marked by commands that could be issued but not reliably carried out, and by legal authority that lacked practical effect.

These constraints explain why rulers so often turned to negotiation rather than sustained repression. Economic noncooperation transformed political conflict into a problem that force could not solve without unacceptable losses. Concessions, charters, and negotiated limits on authority restored circulation and stabilized revenue at lower cost than coercion. Lords did not abandon force as a principle, but they learned its limits. In a political economy dependent on exchange, authority that destroyed cooperation destroyed itself. Force could defend power, but it could not sustain it.

Charters, Concessions, and the Institutionalization of Limits

The concessions extracted through economic noncooperation did not remain informal or temporary. They were translated into written charters that formalized limits on lordly authority and stabilized new political relationships. These documents did not represent spontaneous acts of generosity on the part of rulers. They were negotiated settlements produced under fiscal pressure, often following prolonged disruption of revenue and administration. Charters recorded the terms under which cooperation would resume, converting economic leverage into durable legal recognition.

Charters typically addressed practical matters rather than abstract rights, reflecting the concrete disputes that had precipitated resistance. They confirmed exemptions from arbitrary tolls, regulated taxation procedures, limited interference in guild governance, and secured judicial autonomy for urban courts. Such provisions were not philosophical statements about liberty but operational rules governing everyday interaction between towns and rulers. By fixing these terms in writing, towns reduced the uncertainty that made future noncooperation necessary, clarifying expectations on both sides. For rulers, charters offered a pragmatic solution to recurring fiscal instability. Accepting limits in law was often cheaper and more reliable than attempting to enforce authority through coercion that risked renewed disruption. Law emerged not as an instrument imposed unilaterally from above, but as a framework negotiated under sustained economic pressure.

The institutionalization of limits also altered the nature of authority itself in more profound ways. Once codified, privileges could be invoked as precedent, defended in courts, cited in correspondence, and transmitted across generations. Charters transformed concessions granted under duress into normalized expectations that shaped political culture over time. Lords found it increasingly difficult to retract privileges without triggering renewed resistance or undermining their own legitimacy, particularly when earlier agreements could be produced in written form. The existence of documentary records constrained future action, binding authority to rules it had previously accepted. Power became procedural, operating within defined boundaries and legal forms rather than through discretionary command alone.

These developments had cumulative effects. As towns acquired multiple charters confirming overlapping privileges, their autonomy thickened into a legal and administrative reality. Councils gained greater control over taxation and justice, guilds secured regulatory authority, and urban communities negotiated directly with higher powers, bypassing intermediate lords. Economic noncooperation did not abolish hierarchy, but it reorganized it. Authority flowed through recognized channels of negotiation rather than unilateral extraction, embedding restraint within the ordinary operation of governance.

The broader significance of charters lies in their demonstration that limits on power were not imposed solely through rebellion or ideology. They emerged through repeated encounters in which economic withdrawal forced rulers to accommodate institutional change. Charters were the residue of these encounters, preserving the outcomes of noncooperation long after markets reopened and payments resumed. By institutionalizing limits, towns converted episodic resistance into enduring structure. What began as refusal ended as law.

Rethinking Medieval Resistance

Medieval resistance has often been framed through the lens of revolt, violence, and popular uprising, emphasizing moments when authority was openly challenged and order visibly disrupted. This focus has shaped both scholarly narratives and public imagination, privileging dramatic episodes such as peasant rebellions, urban riots, and armed confrontations. Such events are visible, narratively compelling, and well represented in chronicle sources that favored spectacle over process. Yet this emphasis distorts the broader landscape of political pressure in the medieval world. It overlooks quieter forms of resistance that were less dramatic but far more durable. Economic noncooperation forces a reconsideration of what resistance looked like in practice, revealing strategies that operated without banners, battlefields, or explicit declarations. Withdrawal, delay, and coordinated inaction rarely appeared in chronicles as moments of crisis, but they reshaped power relationships with lasting effect.

Viewing resistance through this lens shifts attention away from ideology and toward structure. Towns did not need a language of rights or a theory of liberty to challenge authority effectively. Their leverage derived from position within economic systems rather than from revolutionary intent. Noncooperation worked precisely because it did not seek to overthrow rulers or reject hierarchy outright. Instead, it exploited the everyday dependencies that made governance possible. Resistance was embedded in routine behavior, blurring the line between political action and ordinary economic decision-making.

This perspective also helps explain why economic refusal proved more successful than rebellion in securing lasting change. Revolts invited repression, generated fear, and often ended with executions, confiscations, and the erosion of communal capacity. Even when rebellions achieved temporary concessions, they tended to leave little institutional residue once force was reapplied. Noncooperation, by contrast, preserved urban institutions and avoided triggering the full coercive apparatus of the state. By framing conflict as negotiation rather than insurrection, towns maintained continuity in governance while steadily applying pressure. The outcomes of resistance were more likely to be absorbed into law, administration, and custom. Limits on authority emerged not from moments of rupture, but from repeated interactions that gradually reshaped expectations, norms, and legal frameworks on both sides.

Rethinking medieval resistance in this way challenges assumptions about power and agency in premodern societies. It suggests that political influence was not monopolized by those who wielded arms or articulated ideology but could be exercised through control of exchange and cooperation. Medieval towns demonstrated that refusing to participate could be as consequential as rebelling, and often more effective. Resistance was not always loud or heroic. Sometimes it was disciplined, patient, and profoundly structural.

Conclusion: When Money Stops Moving Upward

The experience of medieval towns demonstrates that political power was never sustained by force alone. Lordship depended on continuous economic cooperation that could not be compelled indefinitely through coercion. Markets, labor, credit, and administration formed the invisible infrastructure of authority, and towns occupied critical positions within that system. When urban communities learned to withdraw participation without rebelling, they revealed a structural truth: control over armed force meant little when exchange ceased to function. Authority could punish, but it could not produce.

Economic noncooperation succeeded precisely because it avoided the language and posture of revolt while striking at the material foundations of rule. By refusing rather than confronting, towns preserved institutional continuity even as they imposed mounting costs on rulers. Closed markets reduced toll income, delayed payments destabilized fiscal planning, and disrupted trade strained credit relationships that lords relied upon to govern. These pressures accumulated quietly, often without a single moment of crisis that could justify violent retaliation. The strategy protected urban capacity, limited the political legitimacy of repression, and allowed concessions to be framed as negotiated settlements rather than humiliating defeats. These settlements accumulated into charters and legal norms that embedded restraint within the ordinary operation of governance.

The long-term significance of these dynamics lies in their cumulative and structural effect. Repeated episodes of economic refusal reshaped expectations about authority, cooperation, and obligation on both sides of the political relationship. Rulers learned that extraction required consent, while towns learned that participation was leverage. Power became increasingly procedural, bounded by agreements forged under economic pressure rather than asserted through discretionary command. Medieval towns did not dismantle hierarchy or abolish lordship, but they reconfigured it by binding rulers to systems of exchange they could not easily dominate or bypass. Limits on authority emerged not from ideology or revolution, but from the repeated demonstration that governance without cooperation was fiscally and administratively unsustainable.

When money stopped moving upward, authority had to listen. This lesson, learned and relearned across medieval Europe, reveals a foundational principle of political economy. Power is strongest where participation is voluntary and weakest where it must be coerced. Medieval towns understood this long before modern theories of resistance articulated it. Their history reminds us that withdrawal can be as powerful as defiance, and that the quiet refusal to cooperate can reshape systems of rule more effectively than open rebellion.

Bibliography

- Berman, Harold J. Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983.

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society. Translated by L. A. Manyon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Britnell, Richard. The Commercialisation of English Society, 1000–1500. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993.

- Dollinger, Philippe. The German Hansa. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1970.

- Epstein, Steven A. An Economic and Social History of Later Medieval Europe, 1000–1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- —-. Freedom and Growth: The Rise of States and Markets in Europe, 1300–1750. London: Routledge, 2000.

- —-. Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Hibbert, A. B. “The Origins of the Medieval Town Patriciate.” Past & Present 3 (1953): 15-27.

- Hilton, Rodney. Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381. London: Routledge, 1973.

- —-. Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism. London: Verso, 1985.

- Mate, Mavis. “The Economic and Social Roots of Medieval Popular Rebellion: Sussex in 1450-1451.” The Economic History Review 45:4 (1992): 661-676.

- Munro, John H. “Industrial Transformations in the North-West European Textile Trades, c.1290–c.1340.” In Before the Black Death: Studies in the ‘Crisis’ of the Early Fourteenth Century, Bruce M. S. Campbell, ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991, 110-148.

- Osland, Daniel. “The Role of Cities in the Early Medieval Economy.” Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean 35:3 (2023): 343-363.

- Pirenne, Henri. Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1925.

- Reynolds, Susan. Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- —-. Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Robinson, W. C. “Money, Population and Economic Change in Late Medieval Europe.” The Economic History Review 12:1 (1959): 63-76.

- Tilly, Charles. Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1990. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.03.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.