The problem of scandal under sacred or mythic authority is not the absence of evidence but the irrelevance of evidence once legitimacy is settled in advance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Power Determines Truth

In societies where political authority is understood as sacred, truth does not function as an independent category. It is produced, filtered, and stabilized through power itself, embedded in ritual language, theological assumption, and political necessity. Ancient Near Eastern kingship offers one of the clearest historical laboratories for observing this dynamic because authority there was not merely administrative or coercive. It was cosmological. Kings ruled not only by force or tradition but by divine sanction, positioned as essential intermediaries between gods and people, order and chaos, fertility and collapse. Law, justice, and prosperity flowed through the ruler’s legitimacy, making the king a structural requirement for the world to make sense. Within such a system, accusations against the ruler did not simply threaten an individual officeholder or dynasty. They threatened the coherence of the moral and cosmic order itself. To accept royal wrongdoing as real would have implied that the gods had erred, abandoned the land, or allowed chaos to rule. As a result, scandal was not processed as evidence to be weighed. It was neutralized as disorder, impiety, or deception before it could ever take root.

What follows argues that sacred kingship generated what can be described as epistemic immunity. Once a ruler was believed to be divinely chosen or indispensable, evidence of wrongdoing became structurally suspect before it was ever evaluated. Royal inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia rarely acknowledge moral failure, abuse, or impiety on the part of the king. Instead, they present an unbroken narrative of righteousness, strength, and divine favor while meticulously cataloging the alleged crimes of enemies and rivals. This asymmetry was not accidental. It was foundational. The king’s legitimacy preceded facts, shaping which claims could be believed and which had to be dismissed.

Scandal in this context did not destabilize authority. It activated mechanisms of denial that preserved it. Accusations were reframed as foreign propaganda, sacrilege, or rebellion. Disbelief in the king’s virtue was itself treated as a form of political or religious deviance. The result was a closed moral economy in which the king could fail militarily, economically, or administratively without ever being wrong. Responsibility migrated outward to traitors, hostile gods, or cosmic tests, while the ruler remained symbolically intact. Denial should not be understood as deception alone. It functioned as governance.

The relevance of this ancient pattern is not confined to antiquity. Modern political systems formally reject divine monarchy, yet they frequently reproduce its logic through charismatic authority, nationalist myth, and loyalty-based epistemologies. In the contemporary United States under President Donald Trump, belief in legitimacy has often preceded belief in facts, with criminal allegations reframed as persecution and critics cast as enemies rather than witnesses. The purpose of this essay is not to collapse ancient kingship into modern politics, but to use Mesopotamian evidence to clarify a recurring historical phenomenon. When power determines truth, evidence loses its force, and scandal becomes not a threat to authority but a test of belief.

Sacred Kingship in the Ancient Near East

Kingship in the ancient Near East was never a purely political institution. It was a theological condition embedded in the structure of the cosmos itself. From Sumer through Babylonia and Assyria, the king was understood as chosen by the gods, installed to maintain order, justice, and stability in a world perpetually threatened by chaos. This divine election did not require moral perfection, but it did require continuity. The removal or delegitimization of a king was not simply a change in leadership. It risked unraveling the relationship between gods, land, and people. As a result, kingship was framed less as an office subject to evaluation and more as a necessity to be preserved.

Near Eastern royal ideology emphasized the king’s role as mediator rather than originator of power, a distinction that carried profound political consequences. Authority flowed downward from the divine realm, passing through the king to society at large, rendering obedience a religious act rather than merely a civic one. In inscriptions and ritual texts, kings repeatedly described themselves as shepherds appointed by the gods, entrusted with protecting the weak, enforcing justice, and ensuring agricultural fertility. Yet this language of care and stewardship functioned as insulation as much as obligation. By locating responsibility in divine appointment rather than human consent, the ideology made criticism appear not simply disloyal but cosmologically dangerous. If justice failed or disaster struck, the problem lay not in the king’s legitimacy but in human disobedience, ritual impurity, divine testing, or hostile forces beyond the realm. The king remained framed as the remedy even when he presided over systemic failure.

This structure produced a crucial asymmetry between ruler and ruled. While subjects owed obedience, labor, and loyalty, the king owed no reciprocal transparency or justification to the population. Accountability was vertical rather than horizontal, directed upward toward the gods rather than outward toward society. Omens, rituals, and priestly consultations functioned as instruments of divine communication, but they did not operate as restraints on royal behavior in any modern sense. Instead, they reinforced the idea that legitimacy was validated through signs interpreted by elites rather than through observable conduct. Even corrective rituals, such as symbolic substitution or temporary ritual humiliation, served to preserve the institution rather than question it. Kingship could be ritually adjusted without ever being politically interrogated.

The indispensability of the king was further reinforced by historical memory. Periods of disorder, invasion, or dynastic collapse were remembered as times when proper kingship had failed or been absent. Texts describing chaos emphasized famine, injustice, and cosmic imbalance, implicitly teaching that even flawed kingship was preferable to no kingship at all. This memory shaped political imagination. Stability did not require a good king so much as a king. Sacred authority created a hierarchy of fears in which the danger of delegitimization outweighed the danger of abuse.

Within this framework, moral failure did not automatically undermine authority, nor was it expected to do so. Kings could be violent, deceptive, or cruel without forfeiting legitimacy, provided they maintained ritual correctness and divine favor. Sacred kingship did not deny the possibility of royal wrongdoing. It denied the relevance of that wrongdoing to the question of rule itself. Evidence of abuse, injustice, or impiety could exist without destabilizing authority because legitimacy had already been settled in advance. Once kingship was sacralized, belief in the ruler’s necessity preceded and overrode moral evaluation. This structure laid the groundwork for the systematic denial of scandal, the inversion of accusation, and the transformation of disbelief into deviance that would later appear so prominently in royal inscriptions and political narratives.

Royal Inscriptions and the Architecture of Denial

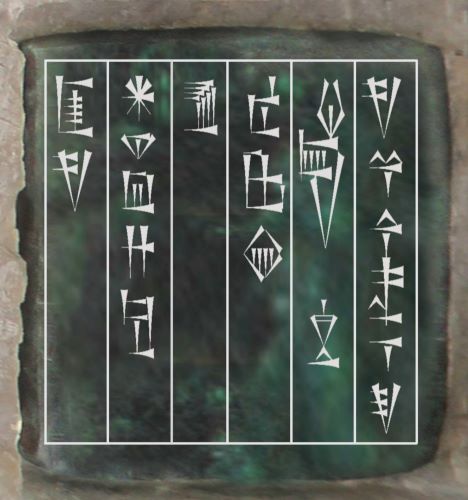

Royal inscriptions in the ancient Near East were not neutral records of events or transparent accounts of governance. They were carefully constructed political texts designed to assert legitimacy, demonstrate divine favor, and foreclose doubt before it could emerge. Carved into stone, cast in metal, or impressed into clay, these inscriptions were meant to endure, projecting authority across time as well as space. Their audience was not only contemporary subjects but future generations, gods, and rival powers. As such, they presented kings as unfailingly righteous, victorious, and pious, regardless of historical complexity or contradiction. The function of these texts was not to persuade through evidence or explanation. It was to stabilize belief through repetition, ritualized language, and the sheer weight of royal authority. Governance became a textual performance in which reality itself was narrated from above, and contradiction had no sanctioned place within the official record.

One of the most striking features of these texts is the total absence of royal self-critique. Military campaigns are always successful, cities are always subdued justly, and violence is framed as divinely mandated punishment rather than political aggression. When failure cannot be ignored, it is displaced onto external causes such as treacherous allies, oath breakers, or hostile gods angered by the sins of others. This narrative pattern creates an illusion of moral consistency by ensuring that the king himself never appears as the source of disorder. Wrongdoing exists only outside the body of legitimate authority.

At the same time, royal inscriptions exhibit an obsessive attention to the alleged crimes of enemies. Rival kings, rebellious cities, and foreign peoples are described as deceitful, impious, lawless, and deserving of destruction. Their resistance is never framed as political disagreement or grievance. It is criminalized as sacrilege or betrayal of cosmic order. By monopolizing moral language, the king positions himself as the sole credible narrator of justice. Accusation flows outward but never inward, creating a closed epistemic system in which evidence against the ruler cannot be articulated within the accepted vocabulary of power.

This architecture of denial was not incidental to kingship. It was constitutive of it. Royal inscriptions did not merely omit inconvenient truths or exaggerate successes. They structured reality itself in such a way that those truths could not meaningfully exist within the political imagination. To accuse the king of abuse, impiety, or injustice was to speak in a register already defined as false, rebellious, or foreign. Language itself had been preemptively captured. Denial functioned less as a reaction to scandal than as a preventative framework that made scandal unintelligible. By establishing legitimacy as unquestionable and dissent as criminal, Near Eastern kingship ensured that belief would always precede evaluation, that loyalty would be measured by acceptance rather than inquiry, and that authority would remain insulated from contradiction even in the face of visible harm.

Scandal, Sacrilege, and the Reversal of Accusation

In the political theology of the ancient Near East, scandal was not treated as a problem of evidence but as a threat to order. Allegations against kings did not circulate as neutral claims awaiting verification. They were immediately reclassified as acts of sacrilege, rebellion, or foreign deceit. This reflexive reframing reveals a crucial feature of sacred authority. The king’s moral standing was not something to be tested. It was something to be defended as a condition of cosmic stability. To accuse the ruler was not merely to question a person but to disrupt the alignment between gods, land, and law.

The mechanism that made this possible was the systematic reversal of accusation, a process deeply embedded in royal language and ritual practice. Rather than addressing claims of abuse, impiety, or injustice, royal discourse transformed accusers into criminals whose speech itself constituted an offense. Dissenters were labeled oath breakers, liars, or enemies of the gods, categories that carried both moral and legal weight. Political opposition was redescribed as religious deviance, collapsing disagreement into transgression. This reversal did not require refutation of specific charges, nor did it depend on counterevidence. It operated by redefining the act of accusation itself as illegitimate, dangerous, and destabilizing. By shifting attention away from the content of the claim and toward the supposed character, loyalty, or ritual purity of the claimant, kingship rendered scandal inert without ever engaging it directly.

This strategy relied heavily on the fusion of political loyalty with religious fidelity, a fusion that left little room for independent judgment. In Mesopotamian ideology, obedience to the king was inseparable from obedience to the gods who had chosen him, and loyalty was expressed through acceptance rather than inquiry. To doubt the ruler’s righteousness was to doubt divine judgment itself. As a result, disbelief became a moral failure rather than a rational stance. The accused king did not need to prove innocence because innocence was presumed by virtue of office and election. The burden of proof shifted entirely onto the accuser, who now had to explain not only the allegation but also the audacity, impiety, and presumed disloyalty involved in making it. In practical terms, this inversion made sustained critique socially and politically untenable.

The reversal of accusation also served an important pedagogical function. It taught subjects how to interpret conflict and failure. When unrest occurred, the proper question was not whether the king had erred but which disloyal forces had provoked divine displeasure. When violence escalated, it was explained as necessary punishment rather than abuse. This interpretive framework narrowed the range of imaginable causes for suffering and injustice. Structural critique became impossible because all negative outcomes were already explained by moral failure elsewhere in the system.

Scandal was transformed into a loyalty test rather than a moment of reckoning. Acceptance of the king’s narrative signaled belonging, while skepticism marked one as suspect, unclean, or politically dangerous. The political effect was profound. Authority no longer depended on convincing subjects of the ruler’s virtue or competence. It depended on compelling them to choose sides epistemically, aligning belief with power. Sacred kingship converted accusation into proof of guilt, not for the accused, but for the accuser. In doing so, it ensured that moral outrage would never mature into political accountability, remaining instead a tool for identifying enemies within.

Epistemic Immunity and the Politics of Belief

Epistemic immunity describes a condition in which authority is shielded from falsification because belief in its legitimacy precedes and overrides the evaluation of evidence. In the context of ancient Near Eastern kingship, this immunity was not an accidental byproduct of power but one of its central functions. Once a ruler was understood as divinely chosen and cosmically necessary, the question of whether accusations were true became secondary to the danger posed by believing them. Knowledge itself was subordinated to stability. Truth was not discovered through inquiry but inherited through loyalty.

This structure inverted ordinary standards of credibility in ways that profoundly reshaped political life. Evidence against the king was not weighed on its merits but filtered through assumptions about who was permitted to speak truthfully and whose speech was inherently suspect. Royal authority established a hierarchy of knowers in which the king and his sanctioned institutions occupied the highest epistemic position. Priests, diviners, and scribes could interpret omens, texts, and signs, but always within tightly constrained boundaries that preserved royal legitimacy. Their role was not to test authority but to stabilize it through interpretation. Subjects, by contrast, were not expected to assess claims critically or compare competing accounts. They were expected to recognize authority as a given and conform their beliefs accordingly. In such a system, disbelief did not arise from ignorance alone. It was actively discouraged as a social and moral failure.

Epistemic immunity also depended on the fusion of belief with identity, a fusion that transformed cognition into a political act. Acceptance of the king’s righteousness functioned as a marker of belonging, ritual purity, and loyalty, while skepticism signaled deviance, impurity, or subversion. Belief was no longer primarily about persuasion or conviction. It was about alignment with power. Once belief became a social obligation, contradiction could be dismissed without engagement, and doubt could be pathologized rather than addressed. To entertain the possibility that an accusation might be true was to risk exclusion, punishment, or worse. Denial did not need to be enforced solely from above. It was reproduced horizontally through fear, conformity, ritual affirmation, and the internalization of sanctioned narratives. The politics of belief extended outward from the palace into households, temples, and public life.

The consequence of this system was a political culture in which scandal could accumulate without consequence. Evidence did not fail because it was weak. It failed because it was inadmissible. Sacred kingship did not require subjects to believe specific claims so much as to reject the very practice of questioning authority. Epistemic immunity ensured that power remained intact not by disproving wrongdoing, but by making wrongdoing irrelevant to legitimacy. In doing so, it transformed belief from a response to facts into a prerequisite for social and political survival.

When Kings Cannot Be Wrong: Failure without Accountability

Sacred kingship did not deny the existence of failure. It denied the possibility that failure could be attributed to the king in a way that threatened legitimacy. Military defeat, economic collapse, famine, and social unrest were all recognized realities in the ancient Near East, documented in chronicles, omens, and lamentations. What distinguished sacred authority was not its capacity to prevent these outcomes but its ability to survive them intact. Failure was acknowledged only insofar as it could be displaced, ritualized, or externalized, never internalized as evidence of misrule. The king remained symbolically unblemished because accountability was not framed as a political requirement of rule but as a theological impossibility. To hold the king responsible in any enduring sense would have implied that divine selection itself was flawed, a conclusion the system was structurally incapable of entertaining.

When military campaigns failed or produced ambiguous results, royal narratives did not interpret these outcomes as evidence of poor judgment or overreach. Instead, they were explained as temporary divine displeasure, insufficient ritual observance, or the treachery of allies and subjects. Defeat became a test rather than a verdict. The king’s role shifted from decision maker to ritual respondent, responsible not for strategy but for appeasement. This move preserved authority by relocating causality away from human agency and into the realm of divine intention. Correction, where it occurred, took the form of rites, prayers, and offerings rather than policy change or leadership replacement.

Economic failure followed a similar pattern, though its effects were often more pervasive and prolonged. Famine, labor shortages, disrupted trade, and declining agricultural yields were framed as cosmic disturbances rather than administrative breakdowns. Texts describing scarcity emphasized improper worship, broken oaths, or moral decay among the population, casting suffering as collective fault rather than institutional failure. The king appeared not as the cause of hardship but as the divinely appointed mediator tasked with restoring balance through renewed devotion and ritual precision. Even when royal policies exacerbated inequality or extraction, the narrative logic redirected blame downward or outward. By transforming economic crisis into a moral and religious problem, sacred kingship converted material deprivation into further justification for the ruler’s indispensability.

Even violence inflicted by the state was insulated from moral scrutiny. Mass punishment, deportations, and executions were presented as just responses to rebellion or impiety, never as abuses of power. The language of necessity dominated these accounts. Violence was described as required to restore balance, enforce divine law, or prevent greater chaos. Because legitimacy was settled in advance, the scale or brutality of punishment did not invite evaluation. The question was not whether the king had gone too far, but whether resistance had made such measures unavoidable.

The result was a political system capable of enduring repeated failure without reform. Sacred kingship did not collapse under the weight of contradiction because contradiction had no recognized pathway to accountability. Authority was preserved not through success but through indispensability. As long as the king remained the symbolic anchor of order, his errors could be endlessly reframed, absorbed, and forgotten. Failure without accountability was not a flaw in the system. It was one of its defining features.

From Sacred Kings to Modern Political Myth

The decline of divine monarchy did not eliminate the structures of belief that sustained it. Instead, those structures migrated, adapting to new political forms while preserving their core logic. Modern states rejected kings chosen by gods, yet they retained narratives of indispensability, exceptionalism, and moral exemption. Authority was secularized, but legitimacy continued to rely on mythic foundations that preceded evidence. The result was not the disappearance of sacred power but its translation into new idioms, including nationalism, popular sovereignty, and charismatic leadership.

In this transformation, the divine source of authority was replaced by abstractions treated with similar reverence and emotional investment. The nation, the people, history, and destiny assumed roles once occupied by the gods, functioning as transcendent reference points beyond ordinary dispute. Leaders increasingly presented themselves not as rulers subject to judgment but as embodiments of collective will, historical inevitability, or civilizational mission. This rhetorical move preserved epistemic immunity by shifting the ground of legitimacy away from personal conduct and toward symbolic representation. To challenge the leader was no longer to defy divine command but to betray the nation, disrespect the people, or undermine the arc of history itself. The sacred was not abolished. It was redistributed across secular myths that carried the same resistance to falsification.

Charismatic authority proved especially effective at reproducing ancient patterns of belief, even in societies formally committed to rational-legal governance. As Max Weber observed, charisma suspends ordinary norms by grounding legitimacy in perceived exceptionalism rather than rule-bound procedure. Modern charismatic leaders cultivate identification rather than accountability, encouraging followers to see attacks on the leader as attacks on themselves. When followers believe a leader uniquely represents them or alone can resolve crisis, criticism is reinterpreted as hostility, sabotage, or elite conspiracy. Evidence becomes secondary to emotional alignment. The leader’s flaws are reframed as proof of authenticity, persecution, or strength rather than failure, echoing the ancient logic that insulated sacred kings from moral evaluation.

Modern media ecosystems have further intensified this dynamic. Whereas ancient kings relied on inscriptions and ritual performance to stabilize belief, contemporary leaders operate within continuous narrative environments that reward repetition and emotional coherence over verification. News cycles, social platforms, and partisan networks function as distributed priesthoods, interpreting events in ways that preserve legitimacy. Contradictory information is not debated but dismissed as biased, corrupt, or malicious. The architecture of denial once carved in stone now circulates digitally, faster and more pervasively than any royal stele.

Political myth thrives particularly in periods of instability. Economic disruption, demographic change, and perceived loss of status create conditions similar to those that once justified sacred kingship. When institutions appear weak and the future uncertain, the appeal of indispensable authority grows. Leaders who promise restoration, protection, or greatness are granted leeway unavailable under normal conditions. Failure is tolerated because the alternative, imagined as chaos or betrayal, seems worse. As in antiquity, fear of delegitimization outweighs concern for abuse.

The continuity between ancient sacred kingship and modern political myth does not lie in identical institutions but in shared epistemic structures that transcend time and regime type. In both cases, legitimacy precedes evidence, belief substitutes for evaluation, and denial functions as governance rather than pathology. The lesson of Mesopotamia is not that modern politics has regressed into archaic forms, nor that history simply repeats itself. It is that the cognitive and social mechanisms that protected sacred authority were never dismantled. They remain latent within political culture, activated whenever belief becomes more valuable than proof and loyalty more important than truth.

Trump and the Return of Epistemic Immunity

The political career of Donald Trump illustrates with striking clarity how epistemic immunity can reemerge within a formally secular, constitutional system. Trump’s authority has not depended primarily on persuasion, policy coherence, or factual consistency. It has depended on the prior belief, among his supporters, that his legitimacy is self-evident and indispensable to national survival. Once that belief is established, evidence ceases to function as a corrective mechanism. Allegations of misconduct are not weighed against standards of law or truth but filtered through loyalty and identity. As in sacred kingship, legitimacy precedes facts, and belief determines what counts as reality. The result is not simple disagreement but a reordered epistemic field in which contradiction is anticipated and neutralized in advance.

Criminal investigations, judicial rulings, and documented falsehoods have repeatedly failed to weaken Trump’s standing among his core supporters because they are not experienced as information. They are experienced as attacks. Accusations are reframed as persecution by corrupt elites, hostile institutions, or imagined enemies of the people. This reframing mirrors the ancient reversal of accusation, in which the act of charging the ruler becomes proof of the accuser’s illegitimacy. The content of the charge matters less than the identity and presumed motives of those making it. Evidence is not refuted. It is delegitimized.

Trump’s rhetoric consistently reinforces this epistemic structure. He presents himself as uniquely capable of defending the nation, restoring lost greatness, and confronting hidden threats. In doing so, he positions himself as necessary rather than merely preferable. Failure is not interpreted as disqualifying but as confirmation of struggle against powerful forces. Like ancient kings who framed defeat as divine testing, Trump converts resistance into validation. The more intense the opposition, the stronger the proof that he alone stands between his supporters and chaos.

This dynamic is sustained and amplified by contemporary media ecosystems that function as engines of narrative reinforcement rather than arenas of verification. Partisan outlets, social platforms, and influencer networks act as interpretive authorities, translating events into stories that preserve legitimacy and foreclose doubt. In this environment, contradiction is not resolved through debate but absorbed through repetition and emotional coherence. Judicial decisions, investigative reports, and expert testimony are dismissed as biased artifacts of an illegitimate system rather than engaged as claims requiring evaluation. The architecture of denial once maintained through ritual performance and royal inscription now operates through algorithmic amplification, selective exposure, and constant narrative feedback.

What emerges from this structure is not merely political polarization but a reconfiguration of belief itself. Trump’s supporters are not persuaded despite the evidence. They are loyal because evidence has been rendered irrelevant to legitimacy. This is the hallmark of epistemic immunity. As in ancient Mesopotamia, authority survives not by disproving wrongdoing but by redefining the conditions under which truth can be recognized at all. The danger of this structure lies not in any single leader or movement, but in the demonstration that modern democratic systems remain vulnerable to the same logic that once shielded sacred kings from accountability, allowing power to persist even when its claims collapse under scrutiny.

Why Evidence Fails When Legitimacy Comes First

Evidence fails in political systems where legitimacy is settled in advance because facts do not operate independently of belief. In such systems, information does not arrive as neutral input awaiting evaluation. It arrives already classified as credible or hostile based on its relationship to authority. Once legitimacy is treated as prior and unquestionable, evidence becomes a secondary concern, relevant only insofar as it reinforces what is already believed. The problem is not a lack of facts but the foreclosure of the conditions under which facts can matter.

This failure is structural rather than psychological. It does not depend on ignorance, irrationality, or individual bad faith, nor can it be solved through education or exposure alone. It emerges from social systems that bind belief to identity, loyalty, and belonging. When acceptance of authority becomes a condition of social membership, evidence that threatens that authority becomes personally costly to acknowledge. Individuals learn, often unconsciously, that disbelief carries penalties such as ostracism, suspicion, or loss of status, while conformity offers safety and affirmation. Under these conditions, rejecting evidence is not an act of stupidity or willful blindness. It is a rational adaptation to a political environment that rewards alignment and punishes doubt.

Legitimacy-first systems also collapse the distinction between explanation and accusation, transforming inquiry itself into a hostile act. To present evidence against authority is no longer understood as an attempt to clarify reality or correct error. It is interpreted as an effort to destabilize order, weaken collective identity, or empower enemies. This reframing shifts attention away from the substance of the claim and toward the presumed motives of the speaker. Investigators become saboteurs, witnesses become traitors, and documentation becomes propaganda. The evidentiary process is redefined as aggression, making good-faith engagement impossible without first conceding that the authority in question may be illegitimate. Once that concession is ruled out, evidence cannot function.

The result is a political environment in which exposure does not produce accountability. Revelations accumulate without consequence, and scandal loses its destabilizing force. Authority persists not because it is innocent, but because innocence is no longer the standard by which it is judged. When legitimacy comes first, evidence fails not by being disproven but by being rendered irrelevant. The system protects itself by ensuring that belief, once granted, cannot be meaningfully withdrawn.

Conclusion: Power That Cannot Be Proven Innocent

The problem of scandal under sacred or mythic authority is not the absence of evidence but the irrelevance of evidence once legitimacy is settled in advance. In ancient Mesopotamia, kingship was structured so that wrongdoing could exist without consequence, absorbed by ritual, denial, and accusation reversal. Royal inscriptions, theological frameworks, and political memory worked together to ensure that belief preceded evaluation. The king did not need to be innocent. He needed to remain necessary. Once authority occupied that position, innocence ceased to be a meaningful category.

What makes this structure enduring is its extraordinary adaptability across time and political form. Sacred kingship did not survive because it was historically accurate or morally defensible. It survived because it solved a recurring political problem: how to preserve authority in the face of failure without inviting collapse. By insulating legitimacy from falsification, systems of power could endure military defeat, economic breakdown, public suffering, and moral contradiction without reform. Accountability was not delayed or imperfectly applied. It was structurally excluded from the logic of rule. This exclusion allowed authority to persist even when its claims were visibly contradicted by experience. As divine monarchy declined, this logic did not disappear. It migrated into secular systems that continued to privilege belief, identity, and loyalty over evidence, transparency, and judgment.

The modern return of epistemic immunity demonstrates the fragility of democratic assumptions about truth and accountability. When leaders are treated as embodiments of nation, destiny, or survival, criticism becomes betrayal and investigation becomes attack. Evidence fails not because it is insufficient but because it is inadmissible within the prevailing moral framework. This condition is not produced by ignorance alone. It is produced by political cultures that reward alignment over inquiry and stability over truth. In such environments, exposure does not liberate. It hardens belief.

History does not offer reassurance that truth inevitably prevails. It offers diagnosis and warning. The lesson of sacred kingship is not that societies fall when rulers lie, but that they endure when lying becomes irrelevant to legitimacy. Power that cannot be proven innocent is not weakened by scandal. It is stabilized by denial, reinforced by loyalty, and protected by the refusal to question. Recognizing this pattern does not guarantee resistance or reform, but it clarifies the stakes with brutal precision. Where legitimacy comes first, truth must fight not only denial, but the deeper conviction that authority itself must be preserved at all costs, even when its moral and factual claims have collapsed entirely.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised ed. London: Verso, 1983.

- Assmann, Jan. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Translated by Andrew Jenkins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality. New York: Anchor Books, 1966.

- Borthwick, Bruce M. “Religion and Politics in Israel and Egypt.” Middle East Journal 33:2 (1979): 145-163.

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Brisch, Nicole, ed. Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2008.

- Dzüvichü, Khriereizhünuo and Seng Tong Chong. “Mesopotamian Kingship in the Bronze Age as Portrayed in Sumerian & Babylonian Literature.” Shodhgyan-NU: Journal of Literature and Culture Studies 4:1 (2026): 53-57.

- Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. Edited by Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

- Frankfort, Henri. Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion of the Integration of Society & Nature. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1948.

- Grayson, A. Kirk. Assyrian Royal Inscriptions: From the Early First Millennium BC. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

- Hallo, William W., and J. J. A. van Dijk. The Exaltation of Inanna. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

- Herman, Edward S., and Noam Chomsky. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. New York: Vintage, 1996.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Liverani, Mario. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Michalowski, Piotr. “The Mortal Kings of Ur: A Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia.” In Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World, edited by Nicole Brisch, 33–45. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2008.

- Postgate, J. N. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Radner, Karen. “Royal Decision-Making: Kings, Magnates, and Scholars.” In The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, edited by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson, 358-379. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Smith, Anthony D. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

- Smith, Jonathan Z. Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House, 2018.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

- —-. King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Winter, Irene J. “Royal Rhetoric and the Development of Historical Narrative in Neo-Assyrian Reliefs.” Studies in Visual Communication 7:2 (1981): 2–38.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.04.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.