Watergate stands as a case study in accountability without persuasion, a moment when the system corrected itself despite, not because of, shared belief.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Evidence Stops Convincing

The Watergate scandal is commonly remembered as a reassuring episode in American political history, a moment when institutions functioned as designed and accountability prevailed. This retrospective framing emphasizes investigative journalism, congressional oversight, and the rule of law, culminating in Richard Nixon’s resignation as proof that democratic safeguards ultimately worked. Yet this narrative smooths over the deeper instability that Watergate exposed while it was unfolding. Far from producing immediate consensus, the scandal revealed a widening gap between evidence and belief. Documentation accumulated, testimony multiplied, and constitutional mechanisms activated, but agreement about what these facts meant fractured along partisan lines. Watergate was not merely a test of legality or constitutional process. It was an early rupture in shared political reality, one in which trust in institutions proved far more fragile than faith in procedure.

From the earliest stages of the investigation, Nixon and his defenders framed Watergate not as a criminal inquiry but as a partisan assault. The language of persecution entered public discourse with remarkable speed. Allegations were dismissed as exaggerations, inventions, or coordinated attacks by hostile elites. The phrase “witch hunt,” now deeply embedded in American political rhetoric, emerged as a way to preempt judgment by discrediting the process itself. This framing did not require refuting specific facts. It required undermining confidence in the institutions presenting them. Courts, journalists, and congressional investigators were recast as political actors rather than neutral arbiters, transforming evidence into just another weapon in a partisan struggle.

What made Watergate historically significant was not the existence of criminal behavior, but the failure of documentation to generate consensus. As tapes were revealed, indictments issued, and testimony corroborated, large segments of Nixon’s political base remained unconvinced. Public opinion polling during the scandal reveals persistent partisan division even as the evidentiary record hardened. Belief did not track proof. It tracked identity. Supporters increasingly interpreted new revelations through a lens of suspicion, assuming bad faith on the part of investigators and the press. Watergate marks one of the earliest modern instances in which exposure failed to produce shared judgment, foreshadowing a political culture in which reality itself became contested terrain.

Accountability eventually arrived, but not through mass persuasion. Nixon resigned only after senior Republican leaders informed him that institutional protection had collapsed. Party elites withdrew support not because the public had converged on a shared interpretation of the evidence, but because continued defense threatened the legitimacy of governance itself.

The Political Atmosphere before Watergate: Distrust, Media, and Polarization

By the early 1970s, American political culture was already strained by a deep and accumulating crisis of trust. The Vietnam War had exposed repeated discrepancies between official statements and observable reality, producing what contemporaries openly described as a credibility gap. Successive administrations issued optimistic assessments that collapsed under the weight of battlefield reporting and casualty figures. The release of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 did not merely embarrass government officials. It confirmed for many Americans that deception had been systemic and bipartisan, embedded within the machinery of national security decision-making. Trust eroded not simply because leaders lied, but because documentary evidence revealed that institutions designed to safeguard truth had instead coordinated its distortion. This erosion created an environment in which skepticism toward official narratives became not cynical, but rational, and in which faith in institutional integrity was already severely compromised before Watergate began.

Domestic unrest further intensified this atmosphere of fracture and suspicion. The late 1960s and early 1970s were defined by mass protest movements opposing the war, demanding civil rights, and challenging economic inequality. These movements questioned not only specific policies but the moral authority of governing elites. For Nixon and his supporters, however, protest was reframed as chaos rather than dissent, and critique as disloyalty rather than democratic engagement. Nixon’s electoral strategy deliberately exploited this divide. By appealing to a “silent majority” allegedly besieged by demonstrators, intellectuals, and cultural elites, he transformed political disagreement into a struggle over social identity and moral order. This framing encouraged supporters to see institutions associated with reform, criticism, or exposure as hostile forces rather than legitimate participants in governance. Polarization hardened not around policy alone, but around competing visions of legitimacy itself.

The media environment also underwent significant transformation during this period. Television had become the dominant source of political information, bringing images of war, protest, and state violence directly into American homes. While this visibility expanded public access to information, it also intensified suspicion. For many viewers, televised reporting appeared selective, sensationalized, or hostile to traditional values. Nixon consistently portrayed the national press as biased and adversarial, cultivating distrust toward journalists long before Watergate erupted. This preexisting hostility meant that later investigative reporting would be interpreted through an already polarized lens.

Nixon’s relationship with institutions extended beyond the media. He viewed the federal bureaucracy, intelligence agencies, and even elements of the judiciary as politically unreliable and insufficiently loyal. This suspicion shaped both his governing style and his rhetoric. Loyalty was prized over expertise, and dissent within government was treated as subversion rather than debate. These attitudes did not remain confined to the executive branch. They filtered outward to supporters, reinforcing the belief that institutional checks existed not to uphold constitutional order but to constrain political power selectively. By the time Watergate occurred, many Americans had already been conditioned to see oversight itself as a partisan act.

Polarization during this period was not merely ideological but epistemic. Americans increasingly disagreed not only about policy outcomes but about which sources of information were credible and which authorities were entitled to judgment. Competing realities formed, each sustained by its own networks of media, rhetoric, and cultural identity. In this environment, evidence did not circulate as a shared resource subject to collective evaluation. It was filtered through prior commitments about loyalty, threat, and belonging. Facts that reinforced group identity were absorbed. Those that challenged it were dismissed. This epistemic fragmentation made consensus increasingly unattainable even when documentation was abundant and corroborated.

Watergate entered this fractured landscape rather than disrupting it. The scandal did not create distrust so much as activate and concentrate it. Investigations unfolded in a political culture already primed to interpret exposure as attack and accountability as persecution. Understanding this atmosphere is essential for explaining why evidence alone failed to persuade large segments of the public. The collapse of shared reality that Watergate revealed was not sudden. It was the cumulative result of years of institutional strain, media conflict, and identity-driven polarization that preceded the burglary itself.

Watergate as Crime: What Was Known and When

The criminal dimensions of Watergate were evident far earlier than later narratives often suggest. The break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in June 1972 was immediately recognized by investigators as politically motivated rather than incidental. Those arrested were not common burglars. They possessed sophisticated surveillance equipment, significant cash, and demonstrable links to Republican campaign operations. Early reporting established connections between the burglars and the Committee to Re-Elect the President, making it clear that the incident was not an isolated act of trespass. From the outset, Watergate presented itself as a political crime with institutional fingerprints.

As investigations progressed, the scope of wrongdoing widened rapidly and decisively. By late 1972 and early 1973, evidence revealed an organized effort to obstruct justice through hush money payments, coordinated false testimony, and the misuse of executive authority. Testimony from White House aides and campaign officials demonstrated that the cover-up was not improvised but managed, involving senior figures who understood both the legal risk and the political stakes. The discovery of the White House taping system transformed the investigation from inferential to documentary. The recordings preserved presidential conversations in real time, capturing discussions about payments, investigations, and strategies of concealment. In modern terms, Watergate produced an evidentiary record unusually resistant to reinterpretation, combining witness testimony with contemporaneous audio documentation.

What is striking is not the gradual emergence of evidence, but the speed and clarity with which it accumulated. By the time the Senate Watergate Committee began its televised hearings in 1973, the essential architecture of the scandal was already visible. Crimes had been established through indictments, plea bargains, and sworn testimony. Senior officials resigned or were dismissed. The hearings did not introduce suspicion so much as confirm it publicly. Yet the abundance of documentation did not produce uniform judgment. For many Americans, particularly Nixon’s supporters, each new revelation intensified suspicion toward investigators, journalists, and Congress rather than toward the White House. Evidence was absorbed not as clarification but as provocation.

The question of “what was known and when” exposes a critical distinction between proof and persuasion. Watergate demonstrates that documentation does not operate in a neutral civic environment. Knowledge did not compel agreement because institutional trust had already fractured along partisan lines. Facts circulated unevenly, filtered through prior commitments about loyalty, grievance, and legitimacy. The scandal shows that political crime can be exhaustively documented without being universally accepted. What was known mattered less than who was willing to treat that knowledge as authoritative.

“Witch Hunt” as Political Language

The phrase “witch hunt” did not originate with Watergate, but the Nixon administration gave it a distinctly modern and politically potent function. Historically, the term evoked irrational persecution, moral panic, and accusations untethered from evidence, most famously associated with episodes of collective hysteria rather than legal process. Nixon and his defenders repurposed this language to invert the logic of accountability itself. By labeling investigation as persecution, they reframed scrutiny as injustice and inquiry as abuse. The term did not directly deny wrongdoing. Instead, it preemptively disqualified the very mechanisms designed to establish truth. In doing so, it shifted attention away from acts and toward alleged intent, recasting the pursuit of evidence as proof of bias.

Nixon deployed this rhetoric early and with strategic consistency. As the investigation expanded, the White House portrayed prosecutors, journalists, and congressional investigators as politically motivated actors bent on destroying the presidency rather than enforcing the law. This framing was not improvised. It aligned with Nixon’s long-standing suspicion of the press and bureaucratic institutions, allowing supporters to interpret Watergate through familiar antagonisms. The effect was anticipatory. By the time new facts emerged, audiences had already been instructed how to read them. “Witch hunt” functioned as an interpretive shortcut, signaling that evidence need not be examined because its source was presumed illegitimate. The phrase replaced evaluation with reflex.

This language also served a defensive psychological function. Accepting the validity of the investigation would have required supporters to reconcile loyalty with evidence of criminality. The “witch hunt” frame resolved this tension by offering a morally satisfying alternative explanation. Nixon was not compromised. He was victimized. Investigators were not neutral. They were conspirators. In this narrative, disbelief became an act of solidarity rather than denial. The phrase transformed suspicion of evidence into a virtue, aligning emotional loyalty with epistemic dismissal.

The “witch hunt” narrative did not collapse as evidence strengthened. It adapted and expanded. Each new revelation was presented as further confirmation of persecution rather than proof of wrongdoing. The more extensive the investigation became, the more elaborate the alleged conspiracy appeared. This self-sealing logic ensured that no factual development could falsify the claim. Evidence confirmed guilt only for those who trusted institutions. For those who did not, it confirmed malice. In this way, the rhetoric insulated belief from correction, hardening suspicion into a durable worldview and making persuasion increasingly unattainable.

Watergate marks the moment when “witch hunt” entered American political life as a durable rhetorical weapon rather than a descriptive metaphor. It provided a template for future leaders facing investigation, demonstrating how language could preempt accountability by destabilizing trust itself. The significance of this shift lies not in Nixon’s personal use of the phrase, but in its effectiveness. Once political actors learned that delegitimizing the process could neutralize evidence, the conditions were set for a political culture in which investigation no longer implied truth-seeking. It implied attack.

Partisan Epistemology: Why Evidence Failed to Persuade

The persistence of support for Nixon during Watergate cannot be explained by ignorance, censorship, or lack of access to information. By 1973, Americans were exposed to an unprecedented volume of documentation, sworn testimony, and legal analysis through newspapers, nightly television broadcasts, and the nationally televised Senate hearings. Millions watched witnesses testify in real time. The problem was not visibility. It was authority. What fractured was not awareness of facts, but agreement about who had the right to define reality itself. Increasingly, Americans disagreed not only about conclusions, but about which institutions were legitimate arbiters of truth. This divergence marks one of the earliest modern instances of partisan epistemology, a condition in which political identity determines what counts as knowledge and whose evidence deserves belief.

Public opinion data from the period underscores the depth of this divide. While Nixon’s overall approval ratings declined as the scandal unfolded, partisan gaps remained strikingly resilient. Republican voters were consistently more likely than Democrats or independents to dismiss allegations as exaggerated, politically motivated, or irrelevant, even after the release of the Oval Office tapes. Evidence did not narrow disagreement. It sharpened it. New information functioned less as a corrective than as a stress test for loyalty. For many supporters, belief in Nixon became inseparable from belief in a broader political and cultural order perceived to be under siege. To accept the evidence was not simply to revise an opinion. It was to concede ground in a larger conflict over identity, authority, and belonging.

This epistemic division was reinforced by Nixon’s long-standing narrative of embattlement. He consistently portrayed himself as a target of elites, intellectuals, and institutions hostile to ordinary Americans. Watergate evidence entered a discursive environment already primed to interpret exposure as aggression. In such a context, facts did not speak for themselves. They spoke for someone. Each revelation was assessed less on its content than on its perceived origin. Evidence associated with the press, Congress, or the judiciary was presumed suspect because those institutions themselves had been rhetorically positioned as adversaries.

Psychologically, partisan epistemology offered emotional coherence. Accepting the full implications of Watergate required acknowledging that loyalty had been misplaced and that trusted authorities had abused power. This recognition carried personal, social, and moral costs. It threatened one’s standing within a political community and undermined narratives of righteousness and victimhood. Rejecting evidence, by contrast, preserved identity and solidarity. Belief became protective. The refusal to be persuaded was not mere obstinacy. It was an adaptive response to polarization, allowing individuals to maintain consistency and belonging in a political environment where changing one’s mind risked social exile.

Watergate demonstrates a critical limit of democratic accountability. Evidence does not compel persuasion when trust in institutions collapses and epistemic authority fragments. Facts require a shared framework of legitimacy to function politically. Without it, documentation accumulates without resolving dispute, and exposure loses its corrective force. Partisan epistemology transforms proof into noise and disagreement into permanence. The scandal revealed that democratic systems depend not only on transparency, but on a baseline consensus about who is authorized to tell the truth. When that consensus erodes, persuasion yields to power, and accountability becomes contingent, negotiated, and ultimately fragile.

Media, Trust, and the Limits of Exposure

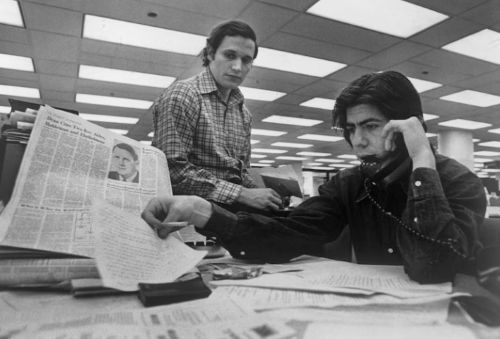

Watergate is often cited as the defining triumph of investigative journalism, a moment when diligent reporting uncovered wrongdoing and forced political accountability. Reporters such as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein are remembered as exemplars of a press fulfilling its democratic role. Yet this celebratory narrative obscures a central limitation that Watergate itself made visible. Exposure did not function as a universal corrective. Information reached the public, but it did not produce uniform judgment. The scandal revealed that journalism’s power depends not only on uncovering facts, but on the presence of trust that allows those facts to matter.

The structure of the media environment in the early 1970s both expanded and constrained journalism’s influence. National newspapers and broadcast networks still dominated information flow, creating a shared stage on which political events unfolded and granting investigative reporting extraordinary reach. At the same time, these institutions were increasingly interpreted through partisan and cultural lenses shaped by the previous decade. Nixon had spent years cultivating skepticism toward the press, portraying journalists as arrogant elites hostile to traditional values and popular authority. This sustained rhetoric primed large segments of the public to treat negative coverage as ideologically motivated rather than evidentiary. As a result, even meticulous reporting could be dismissed not because it lacked credibility, but because its institutional source was already distrusted. The messenger became inseparable from the message.

Televised coverage of the Senate Watergate hearings further illustrates this tension between visibility and persuasion. Millions of Americans watched hours of testimony, observing contradictions, admissions, and corroborated accounts of wrongdoing unfold in real time. In theory, such transparency should have strengthened consensus by allowing citizens to witness evidence directly. In practice, interpretation fractured along partisan lines. Viewers sympathetic to Nixon often focused on procedural disputes, perceived hostility from senators, or the demeanor and credibility of witnesses rather than the substance of their statements. Small inconsistencies were magnified, while larger patterns were discounted. Exposure did not resolve disagreement. It provided raw material for competing narratives to solidify.

This selective interpretation underscores a fundamental limit of media power. Journalism assumes a baseline willingness to accept institutional arbitration of truth, including trust in courts, congressional committees, and professional reporting norms. When that willingness erodes, exposure becomes insufficient. Reporting can document, contextualize, and repeat, but it cannot compel belief. Watergate demonstrates that media influence is conditional rather than absolute. Its effectiveness depends on shared assumptions about legitimacy that journalism alone cannot create or restore. Once those assumptions fracture, even overwhelming documentation can coexist with persistent disbelief.

The legacy of Watergate complicates narratives about the press as a corrective force. Investigative journalism succeeded in assembling an extensive and coherent factual record, yet persuasion lagged far behind documentation. Accountability arrived only when political elites withdrew support, not when media exposure reached its peak. This outcome reveals a sobering lesson. Truth can be established without being accepted, and exposure can coexist with denial. The limits of media are not failures of reporting. They are failures of trust.

The Republican Base: Loyalty, Suspicion, and Narrative Control

The durability of Nixon’s support during Watergate cannot be understood without examining the social and political dynamics of the Republican base itself. For many supporters, allegiance to Nixon was not transactional or narrowly policy-based. It was expressive and identity-driven. Nixon symbolized resistance to cultural upheaval, elite condescension, and what his supporters perceived as the erosion of traditional authority. As a result, criticism of Nixon was experienced not merely as political disagreement, but as an attack on the social groups and values he was understood to defend. Loyalty became a form of self-defense rather than passive endorsement.

Suspicion toward institutional actors played a central role in sustaining this loyalty. By the early 1970s, many Republican voters already viewed the press, universities, federal prosecutors, and elements of the civil service as ideologically aligned against them. These institutions were not seen as neutral arbiters but as cultural opponents embedded within the state. Watergate allegations entered this interpretive framework with little resistance. Investigators and journalists were assumed to be hostile before they were heard, their findings discounted before they were evaluated. This preexisting distrust allowed supporters to dismiss even corroborated evidence as procedurally contaminated or politically engineered. The issue was not whether crimes had occurred, but whether the institutions alleging them deserved belief at all.

Narrative control reinforced and stabilized these suspicions. Nixon and his allies consistently framed developments in the scandal as selective, exaggerated, or strategically timed to inflict political damage. Supportive media outlets, party officials, and informal grassroots networks echoed these interpretations, producing a dense feedback loop that insulated belief from external correction. Within this ecosystem, counterevidence was neither ignored nor denied outright. It was absorbed and reframed. Each new revelation became further proof of persecution rather than a challenge to the narrative. The coherence of this alternative explanation mattered more than its factual alignment. The base did not suffer from an information deficit. It possessed an internally consistent story that rendered contradiction intelligible and survivable.

This narrative coherence was sustained by a careful separation between private doubt and public defense. Polling data, memoirs, and private correspondence suggest that some Republican voters and officials harbored reservations about Nixon’s conduct as evidence mounted. Yet these doubts rarely translated into open dissent. Public criticism carried tangible social and political costs, including accusations of betrayal and loss of standing within one’s community. Silence, deflection, or conditional defense became safer responses. This gap between private uncertainty and public loyalty widened, reinforcing the outward appearance of unified belief even as internal confidence eroded.

The emotional economy of loyalty further explains this persistence. Accepting Nixon’s guilt would have required supporters to confront not only political disappointment but moral reversal. It would have meant acknowledging that trusted leaders had abused power and that long-standing adversaries had been correct. Such recognition threatened identity, community, and self-respect. Rejecting the evidence, by contrast, preserved coherence and belonging. Loyalty operated not as ignorance or blind faith, but as an emotionally rational strategy in a polarized environment. Disbelief reduced psychological cost even as it strained factual plausibility.

The Republican base’s response to Watergate illustrates a broader transformation in American political behavior. Voters increasingly evaluated events not through institutional channels of verification, but through narrative alignment and identity affirmation. Trust migrated from procedures to personalities, from evidence to affiliation. This shift did not originate with Watergate, but the scandal revealed its consequences with unusual clarity. The persistence of loyalty demonstrated that accountability in democratic systems does not hinge solely on exposure or proof. It depends on whether political communities are willing to allow evidence to disrupt the narratives that sustain them.

Elite Withdrawal: Why Nixon Fell

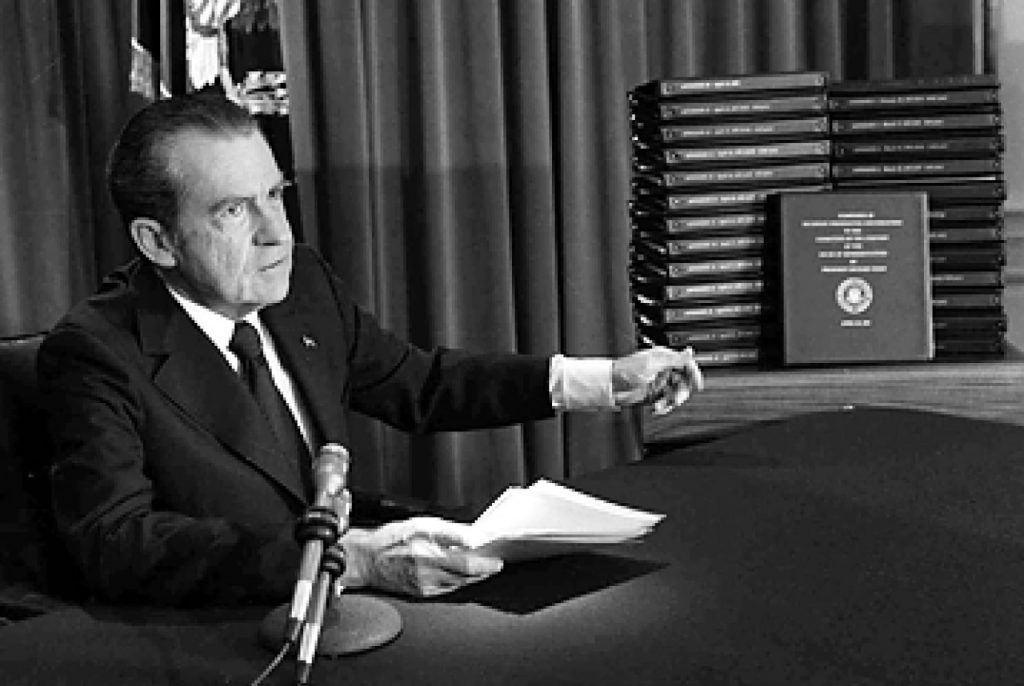

Richard Nixon did not leave office because the American public reached a shared moral or factual conclusion about Watergate. He fell because the institutional elites who had sustained his presidency withdrew their protection. This distinction is essential for understanding the mechanics of accountability in polarized systems. By the summer of 1974, evidence of wrongdoing was exhaustive and increasingly incontrovertible, yet a substantial portion of Nixon’s base remained loyal. Polling data continued to show partisan resilience, and disbelief had not collapsed under the weight of documentation. Public opinion was divided, not convergent. What changed was not mass belief, but elite calculation. Republican leaders came to recognize that continued defense of Nixon threatened not only electoral prospects but the legitimacy of the presidency, the credibility of Congress, and the stability of constitutional governance itself.

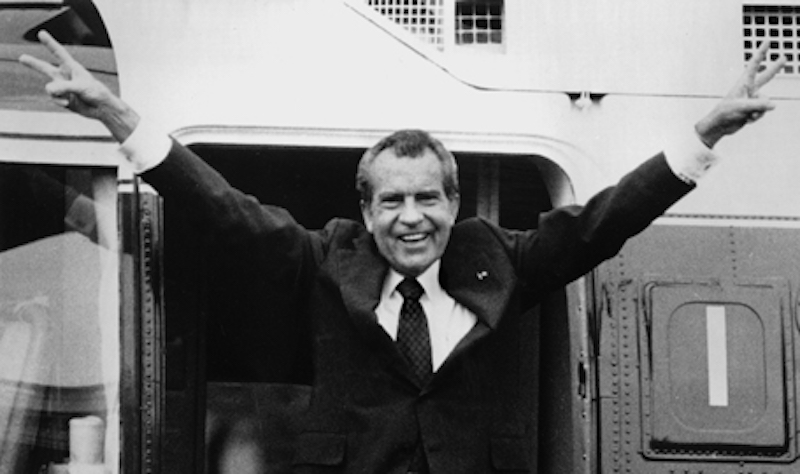

The turning point came not through public persuasion, but through private confrontation and institutional assessment. Senior Republican figures, most notably Senator Barry Goldwater, Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, and House Minority Leader John Rhodes, met with Nixon and delivered a stark message. Support in Congress had evaporated beyond recovery. Impeachment in the House was imminent, and conviction in the Senate was no longer in doubt. This intervention was not framed in moral language. It was not an appeal to conscience or repentance. It was institutional arithmetic. Nixon’s political utility had been exhausted, and his continued presence posed an unacceptable risk to the party and to the structures of authority that elites were invested in preserving. Loyalty, once strategically useful, had become institutionally dangerous.

This moment underscores a structural truth about accountability in polarized systems. When shared reality fractures, public persuasion becomes unreliable as a mechanism of correction. Institutions rely on elite enforcement to restore order. In Watergate, constitutional accountability functioned not because the public was convinced, but because elite actors recognized that disbelief had become unsustainable at the institutional level. The same evidence that failed to persuade voters carried decisive weight among those whose authority depended on procedural legitimacy. Accountability emerged not from consensus, but from strategic withdrawal.

Nixon’s resignation reveals the conditional nature of democratic correction. Power does not fall when truth is established. It falls when those who enable power decide that denial carries greater cost than removal. Watergate is often remembered as proof that “the system works,” but this reading obscures its warning. The system worked only because elites chose to act despite persistent public division. Where such withdrawal does not occur, evidence alone is insufficient. Accountability becomes optional, contingent on the willingness of institutional actors to prioritize legitimacy over loyalty.

Watergate’s Misremembered Legacy

In the decades following Nixon’s resignation, Watergate was gradually transformed into a comforting civic parable, a story retold to reassure rather than to warn. The dominant memory emphasized institutional resilience and moral closure. Journalists exposed wrongdoing, Congress investigated, courts ruled, and the president resigned. This sequence was elevated into proof that American democracy ultimately corrects itself when pushed hard enough. Watergate entered textbooks and popular culture as evidence that transparency, persistence, and constitutional checks reliably prevail. What this narrative obscures is how contingent and fragile that outcome actually was. The system did not move smoothly toward correction. It staggered, resisted, and nearly failed. Accountability emerged not as an automatic consequence of exposure, but as the product of elite decisions made under institutional duress.

This misremembering flattened the epistemic crisis at the heart of the scandal. Watergate did not restore trust in institutions. It exposed how much trust had already eroded before the break-in ever occurred. Large segments of the public rejected the legitimacy of investigations, journalism, and congressional authority even as evidence accumulated. Yet the post-Watergate narrative treated persuasion as inevitable rather than incidental. By focusing on resignation as resolution, memory substituted outcome for diagnosis. The lesson absorbed was that exposure works, not that belief fractured. The unresolved problem of partisan epistemology, visible in polling and public discourse during the scandal, was quietly set aside in favor of a more reassuring story.

The celebratory legacy also mislocated the source of accountability. Popular memory credits investigative journalism and public vigilance while minimizing the decisive role of elite withdrawal. Nixon fell not because the public reached consensus, but because party leaders concluded that continued defense threatened institutional legitimacy. This distinction matters because it shapes expectations about democratic safeguards. If accountability is remembered as the natural product of truth-seeking alone, then the structural conditions that made Watergate exceptional are misunderstood. The courage and calculation of institutional elites become background details rather than central mechanisms.

By misremembering Watergate as a triumph of shared reality rather than a warning about its collapse, American political culture dulled its ability to recognize similar crises later. The comforting narrative implied that denial has natural limits and that truth eventually asserts itself regardless of political conditions. Watergate’s deeper lesson was far more unsettling. Truth prevailed only when power allowed it to prevail. When that allowance was withdrawn, evidence mattered. When it was not, evidence accumulated without effect. Properly understood, Watergate does not guarantee democratic self-correction. It reveals how easily systems can normalize disbelief while retaining the appearance of legality. Its legacy is not reassurance, but a caution about how close democratic institutions can come to functioning without shared reality at all.

From Nixon to the Present: The Long Shadow of Watergate

The epistemic fracture exposed by Watergate did not heal with Nixon’s resignation. It hardened. In the years that followed, American political culture absorbed the lesson that evidence alone does not compel accountability, while simultaneously misremembering the scandal as proof that it does. This contradiction proved consequential. Rather than restoring shared trust, the post-Watergate era normalized suspicion toward institutions and incentivized leaders to treat investigation as partisan threat rather than civic necessity. What Watergate revealed as fragility later became strategy.

Subsequent political actors learned selectively from Nixon’s downfall. They did not conclude that wrongdoing inevitably leads to removal. They concluded that removal occurs only when elite protection collapses. The lesson was not to avoid misconduct, but to manage loyalty more effectively. As partisan polarization intensified in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, leaders increasingly prioritized narrative cohesion within their base over persuasion across institutional or ideological lines. Investigation became something to withstand rather than answer. The rhetorical tools pioneered during Watergate, especially the framing of accountability as persecution, were refined, normalized, and embedded into partisan playbooks. Political survival came to depend less on factual defense than on maintaining distrust toward those presenting evidence.

Media fragmentation accelerated this trajectory dramatically. The relatively centralized media environment of the 1970s, in which a small number of national outlets retained broad public credibility, gave way to a fractured ecosystem defined by partisan media, algorithmic amplification, and identity-driven information streams. Where Nixon confronted a limited set of widely recognized arbiters, contemporary leaders operate within environments where unfavorable reporting can be instantly dismissed as ideologically hostile or illegitimate. This fragmentation did not create partisan epistemology, but it institutionalized it. Competing realities no longer merely coexist at the margins. They are continuously reinforced, rewarded, and insulated from contradiction, making persuasion not just difficult but structurally disincentivized.

The long shadow of Watergate is most visible in the normalization of disbelief. Claims once regarded as politically disqualifying are now treated as background conditions of public life. Documentation that would have ended careers in earlier eras is absorbed, reframed, and endured with minimal consequence. This endurance is not accidental. It reflects a political culture that learned, incrementally, that accountability is conditional rather than automatic. Truth matters only when power allows it to matter. When elite withdrawal does not occur, exposure alone cannot substitute for enforcement.

Watergate stands less as a historical exception than as a threshold moment. It marked the transition from a political culture that assumed shared reality to one that actively contests it. The unresolved epistemic crisis of the 1970s became the operating condition of the present. The mechanisms of denial grew more sophisticated, more routinized, and less shocking. Understanding this continuity reframes Watergate not as a closed chapter with a moral resolution, but as the beginning of a longer story about power, belief, and the limits of democratic correction. The shadow it cast was not temporary. It lengthened, deepened, and reshaped the political landscape that followed.

Conclusion: Accountability without Persuasion

Watergate ultimately reveals a truth more unsettling than the familiar story of democratic triumph. Accountability did not emerge because evidence persuaded the public or because shared reality was restored. It emerged because institutional actors decided that continued denial carried unacceptable cost. The scandal exposed a critical asymmetry in democratic systems. Truth can exist without consensus, and proof can accumulate without persuading those whose identities are bound to power. What matters is not whether corruption is known, but whether those positioned to enforce consequences are willing to act despite fractured belief.

This distinction clarifies why Watergate should be understood less as a victory of transparency than as a warning about its limits. Exposure did its work thoroughly. Journalism, courts, and congressional investigation produced one of the most documented political scandals in American history. Yet persuasion lagged far behind documentation. Large segments of the public remained unconvinced, not because evidence was weak, but because trust in institutions had already collapsed. Accountability arrived only when elite withdrawal substituted for popular agreement. Democratic correction functioned vertically rather than horizontally, imposed by institutional decision rather than collective judgment.

The persistence of this pattern carries sobering implications for the present. If accountability depends primarily on elite enforcement rather than public persuasion, then democratic resilience becomes conditional rather than assured. Systems can absorb extraordinary levels of misconduct so long as power remains unified and disbelief is socially rewarded. Corruption does not need to be concealed to survive. It needs only to be reframed as persecution or dismissed as partisan excess. Under such conditions, truth does not disappear. It remains visible, documented, and accessible. What changes is its political efficacy. Truth becomes inert, incapable of triggering consequence without institutional permission. The danger lies not in ignorance, but in normalization, in the gradual acceptance that exposure alone is no longer enough to demand action.

Watergate stands as a case study in accountability without persuasion, a moment when the system corrected itself despite, not because of, shared belief. Its enduring relevance lies in this uncomfortable insight. Democratic institutions do not collapse only when laws are broken. They erode when belief fractures and loyalty replaces judgment as the primary civic virtue. When accountability depends on elite withdrawal rather than public conviction, democracy survives precariously, balanced between legality and denial. The scandal’s true legacy is not reassurance that the system works automatically, but a reminder of how narrowly it sometimes does, and how easily it might not.

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Nixon: Ruin and Recovery, 1973–1990. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

- Bartels, Larry M. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Bernstein, Carl, and Bob Woodward. All the President’s Men. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974.

- Gould, Lewis L. The Modern American Presidency. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

- Hallin, Daniel C. The Uncensored War: The Media and Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Hetherington, Marc J., and Jonathan D. Weiler. Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Kutler, Stanley I. Abuse of Power: The New Nixon Tapes. New York: Free Press, 1997.

- —-. The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon. New York: Knopf, 1990.

- Perlstein, Rick. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. New York: Scribner, 2008.

- Ritchie, Donald A. “Investigating the Watergate Scandal.” Congressional History 12:4 (1998): 49-53.

- Schudson, Michael. The Power of News. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Sirica, John J. To Set the Record Straight. New York: W. W. Norton, 1979.

- Smoller, Fred. “Watergate Revisited.” PS: Political Science and Politics 25:2 (1992): 225-227.

- White, Theodore H. Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Atheneum, 1967.

- United States House of Representatives. Articles of Impeachment Against Richard Nixon. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974.

- United States Senate. Report of the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974.

- Zelizer, Julian E. The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society. New York: Penguin, 2015.

- —-. Governing America: The Revival of Political History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.04.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.