After Sicily, the empire was already being replaced, not because Sparta immediately surpassed Athens in every dimension, but because the belief in Athenian indispensability fractured.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Sicilian Disaster and the Illusion of Indispensability

The Sicilian Expedition of 415–413 BCE represented the height of Athenian ambition and the clearest expression of imperial overconfidence. Conceived amid the long strain of the Peloponnesian War, the campaign promised strategic expansion, access to resources, and the potential encirclement of Sparta through control of western Greek networks. What began as intervention in a dispute involving Segesta and Syracuse evolved into a vast military undertaking. Athens dispatched one of the largest fleets it had ever assembled, projecting confidence not merely in its naval superiority but in the presumed inevitability of its influence. The decision reflected more than strategic calculation. It revealed an assumption that Athenian power, once deployed, would be decisive and that resistance would ultimately fold before maritime dominance.

The disaster that followed was total. After initial hesitation and internal political turmoil, including the recall and defection of Alcibiades, Athenian forces became bogged down in Sicily. Reinforcements under Demosthenes failed to reverse the tide. By 413 BCE, the fleet was destroyed in the Great Harbor of Syracuse, and thousands of Athenian soldiers were killed or captured. The survivors, according to Thucydides, endured brutal imprisonment in the stone quarries of Syracuse. The scale of the defeat was unprecedented. It was not merely a lost campaign but the annihilation of manpower, ships, and prestige. Athens had gambled imperial credibility on distant expansion and lost catastrophically.

Yet the strategic consequences extended beyond military losses. The Sicilian defeat shattered the aura of inevitability that had long shielded Athenian hegemony. Naval supremacy had functioned not only as force projection but as political signaling. Allies complied in part because resistance appeared futile. Once news of the catastrophe spread, that perception fractured. The empire had relied on the belief that Athens was too powerful to be challenged and too central to be abandoned. Sicily revealed vulnerability. Vulnerability invited recalculation.

The illusion of indispensability dissolved rapidly. Athens had assumed that its maritime network, tribute system, and defensive umbrella made it irreplaceable within the Aegean order. Instead, the defeat signaled to subject allies and rival powers alike that alternatives might be viable. Indispensability, it became clear, had rested on credibility rather than inevitability. Once credibility faltered, loyalty became conditional. The Sicilian failure did not immediately end the war, but it marked the moment when Athenian centrality ceased to appear permanent.

From Mutual Defense to Extractive Empire: The Transformation of the Delian League

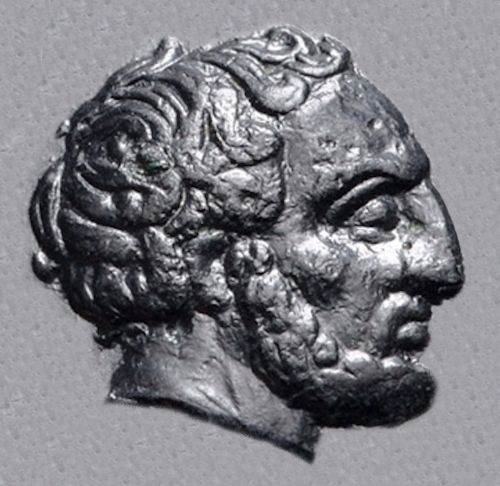

The Delian League began in 478 BCE as a defensive coalition against renewed Persian aggression. Formed in the aftermath of the Persian Wars, the alliance was anchored in shared security and collective naval defense. Member states contributed ships or monetary tribute, and the treasury was initially housed on the island of Delos, a location symbolically neutral and religiously significant. It was renowned as the mythological birthplace of the twin gods Apollo and Artemis. In its early years, the league functioned as a cooperative structure designed to safeguard autonomy in the Aegean. Participation reflected both mutual interest and the prestige of Athenian leadership.

The character of the league gradually shifted. As Persian threats receded, Athens maintained and even intensified tribute collection. Monetary contributions increasingly replaced ship contributions, consolidating naval power in Athenian hands. The transfer of the treasury from Delos to Athens in 454 BCE marked a profound symbolic and practical turning point. What had once been a shared alliance resource became effectively an Athenian imperial treasury. Tribute revenues flowed into the city, funding not only military expenditures but monumental building projects such as the Parthenon. The league’s fiscal mechanism evolved from collective defense financing into an extractive revenue system.

Resistance to this transformation was met with coercion. Revolts by member states, including Naxos, Thasos, and later Mytilene, were suppressed decisively. Defection was no longer treated as voluntary withdrawal from an alliance but as rebellion against imperial authority. The Athenian response to Melos in 416 BCE further revealed the shift in political philosophy. The infamous dialogue recorded by Thucydides portrays Athens asserting power without moral pretense, grounding its actions in necessity rather than justice. The suppression of dissent signaled to allies that membership was compulsory, not contractual.

As coercion increased, the league’s legitimacy eroded. While tribute payments ensured material compliance, they did not guarantee political loyalty. The more Athens relied on force to maintain adherence, the more the alliance resembled domination rather than partnership. Extractive structures can remain stable so long as the central power projects overwhelming strength. Yet they accumulate latent resentment. The transformation of the Delian League embedded structural fragility beneath the appearance of maritime control.

This fragility became more visible as Athenian demands intersected with local political tensions across the Aegean world. Democratic factions within allied cities often aligned with Athenian influence, finding advantage in imperial backing against domestic rivals, while oligarchic elements frequently viewed Athens as an intrusive hegemon undermining traditional authority. Imperial governance reshaped constitutional arrangements and judicial practices. Athens required tribute assessments, standardized coinage in some regions, and access to Athenian courts for certain legal appeals. These measures tightened integration but also deepened perceptions of dependence. Political identity within allied poleis became entangled with imperial alignment. Loyalty to Athens was no longer merely strategic; it became embedded in factional struggles within each city. Such integration increased administrative coherence, yet it magnified the stakes of imperial credibility. If Athens appeared weak, domestic opponents within these cities could seize the opportunity to reverse prior alignments.

By the eve of the Expedition, the League had fully evolved into what modern historians recognize as the Athenian Empire, a system whose cohesion depended not on shared deliberation but on sustained demonstration of power. Its stability rested upon naval enforcement, tribute regularity, and the widespread belief that Athenian leadership remained indispensable to security and economic order in the eastern Mediterranean. This indispensability, however, was performative rather than structural. It required continuous affirmation through visible strength. Once the catastrophic defeat in Sicily disrupted that perception, the extractive character of the system became impossible to obscure. Alliances framed as mutual defense may endure temporary weakness because they rest upon reciprocal benefit. Empires built upon compelled tribute and managed political hierarchies require credibility as a substitute for consent. When that credibility falters, compliance shifts from habitual obedience to strategic calculation. At that point, the very mechanisms that once sustained dominance accelerate fragmentation.

Hedging as Strategy: Why Subject Allies Began Revolting (413–411 BCE)

News of the Sicilian catastrophe did not merely shock the Aegean. It recalibrated risk assessments across the empire in ways that were immediate and profound. Allied poleis that had long endured Athenian tribute demands and political oversight began to reconsider their strategic environment with new urgency. The annihilation of the fleet in 413 BCE suggested not simply temporary weakness but structural vulnerability. Athens had lost ships, soldiers, and commanders on a scale that could not easily be replaced. The psychological effect was as significant as the material loss. If Athens could squander such resources in distant Sicily, it could also fail to suppress revolt closer to home. The perception of inevitability, once central to imperial stability, was punctured. In interstate systems, perception often matters more than immediate capability. The Sicilian defeat altered the psychological balance of power before it altered the material one, inviting calculations that had previously seemed too dangerous to entertain.

Revolts soon followed. Chios, one of the largest and wealthiest allied states, defected in 412 BCE, providing a powerful signal to others that resistance was possible. Miletus joined shortly thereafter, and unrest spread through Ionia and the Hellespont. These decisions were not driven by ideological conversion to Spartan leadership but by recalculated probabilities. If Athenian retaliation now carried higher risk of failure, then rebellion no longer guaranteed annihilation. Defection became strategically thinkable. Once a major ally moved, smaller states gained both precedent and cover.

This pattern reflects what modern political science terms hedging behavior. States facing uncertainty diversify their commitments rather than committing fully to a single dominant power. For subject allies, revolt was not necessarily an act of permanent realignment at first. It was a test of Athenian resilience. If Athens recovered quickly, defectors might face punishment. If Athens faltered, alignment with Sparta would become durable. Hedging operated as a provisional strategy, balancing risk while waiting for further information about the durability of Athenian recovery.

Sparta’s responsiveness amplified this recalibration in decisive ways. Rather than relying solely on its traditional strength in hoplite land warfare, Spartan leadership recognized that Athens’ vulnerability was maritime and political. They moved to encourage revolts diplomatically while also pursuing naval construction, an area in which Sparta had previously lagged behind. The mere prospect of coordinated Spartan intervention changed allied calculations. Rebellion without external backing would have been reckless and potentially suicidal. Rebellion supported by a rival great power, however, became rational risk management. Each Spartan diplomatic overture and each reported shipbuilding effort lowered the threshold for defection among Athenian subjects. The strategic environment shifted from one of unilateral dominance to one of emerging bipolar competition.

Persian involvement intensified this dynamic and transformed hedging into systemic realignment. Satraps such as Tissaphernes offered financial backing to Sparta, enabling the construction and maintenance of fleets capable of contesting Athenian naval supremacy. Persian subsidies did more than provide ships and sailors. They signaled that Athens now faced a coalition with resources deep enough to sustain prolonged resistance. Allies observing this development could reasonably conclude that alternatives to Athenian hegemony were not speculative but materializing with institutional support. The entrance of Persian gold altered the cost-benefit equation of revolt. Hedging was no longer merely defensive caution. It became participation in an emerging counter-network capable of reshaping regional power.

Between 413 and 411 BCE, the Aegean transformed from an imperial hierarchy into a contested arena of shifting loyalties. What appeared to Athens as betrayal was, from the perspective of allied cities, strategic adaptation to altered conditions. When central power projects instability, subordinate actors protect themselves by exploring options. The revolts of this period were not spontaneous eruptions of resentment but calculated responses to declining imperial credibility. Hedging, once begun, rarely reverses quickly. It creates momentum toward systemic reorganization.

Persian Gold and Spartan Coalition-Building

The transformation of the war after 413 BCE cannot be understood without recognizing the decisive role of Persian intervention. For much of the earlier conflict, Sparta had struggled to match Athenian naval capacity. Its strength lay in land warfare and the Peloponnesian alliance system, not in sustained maritime operations across the Aegean. Even when Sparta sought to challenge Athens indirectly, it lacked the financial infrastructure necessary to maintain fleets for extended campaigns. An opening had been created, but opportunity alone was insufficient. What allowed Sparta to convert Athenian vulnerability into strategic momentum was the infusion of Persian financial support. The involvement of the Achaemenid Empire altered the scale, duration, and character of the conflict. A war that had been defined by Greek rivalries increasingly became entangled in imperial geopolitics, as Persian resources were deployed to recalibrate the balance of power in the eastern Mediterranean.

Satraps such as Tissaphernes and later Pharnabazus entered into negotiations with Spartan commanders, offering subsidies in exchange for recognition of Persian interests in Asia Minor. These agreements were pragmatic rather than ideological. Persia sought to weaken Athens and recover influence over Ionian Greek cities, while Sparta sought the resources necessary to challenge Athenian sea power. Persian gold funded shipbuilding, paid rowers, and sustained fleets that would otherwise have been impossible for Sparta to maintain. The arrangement reflected mutual expediency, yet its consequences were profound.

With Persian backing, Sparta transitioned from a primarily terrestrial power into a credible maritime competitor. The construction and maintenance of fleets required sustained revenue streams, something Athens had long secured through tribute from its empire. Persia effectively replaced Athenian tribute as the financial engine of naval competition. This shift destabilized the strategic equilibrium of the Aegean in structural terms. Allied states observing the growing Spartan fleet could no longer assume that Athens held uncontested dominance at sea. Naval warfare was not merely a matter of ships but of wages, timber, supply chains, and long-term funding commitments. Persian subsidies signaled that Sparta’s naval expansion was not a temporary surge but a sustainable alternative. The existence of a funded rival transformed revolt from symbolic resistance into plausible realignment, encouraging allied cities to reconsider their long-term alignment with Athens.

Spartan commanders such as Lysander capitalized on this financial foundation to forge tighter alliances and coordinate operations across the eastern Aegean. Persian subsidies enabled disciplined fleet maintenance and the payment of experienced crews, increasing operational reliability. The coalition that emerged was not merely reactive. It was structured, financed, and sustained with clear strategic intent. Sparta’s naval victories, culminating in decisive engagements later in the war, were inseparable from this material support. Persian gold did not fight the battles directly, but it made sustained naval warfare against Athens feasible.

The broader implication of Persian intervention was systemic. Athenian power had long depended on the perception that no rival coalition possessed comparable resources. Once Persia underwrote Spartan expansion, that perception collapsed. Coalition-building requires both political will and financial capacity. Sparta supplied the former; Persia supplied the latter. Together they constructed an alternative power network capable of absorbing defecting allies and contesting trade routes. In doing so, they demonstrated that imperial dominance is vulnerable not only to battlefield defeat but to the quiet redirection of capital and alliance commitments.

Trade Routes, Naval Power, and Network Reorganization

Athenian power in the fifth century BCE rested not only on tribute and ideology but on control of maritime circulation. The Aegean was an economic artery system linking agricultural hinterlands, mining regions, and commercial centers into a single strategic ecosystem. Grain from the Black Sea, timber from Macedonia and Thrace, silver from Laurion, and manufactured goods from Attica moved along sea lanes protected by Athenian fleets. Naval supremacy ensured that these routes remained open to allies and constrained for enemies. Control of chokepoints such as the Hellespont allowed Athens to regulate access to essential imports, especially grain, which was indispensable to feeding its dense urban population. Maritime dominance was inseparable from economic stability, urban survival, and imperial legitimacy. The empire functioned as a network anchored by naval security, and that security was both military and commercial in character.

When that naval dominance weakened, the economic consequences followed quickly. Revolts in Ionia and along the coast of Asia Minor threatened not only tribute revenue but logistical corridors. If Sparta and its Persian-backed fleets could contest eastern Aegean waters, then Athenian merchants and supply convoys faced risk. Trade networks depend upon predictability. The perception of predictability was disrupted, and subsequent Spartan naval activity intensified uncertainty. Economic actors, like political actors, respond to perceived shifts in protection.

The Hellespont became especially critical in the final years of the war. Athens depended heavily on imported grain, particularly from the Black Sea region. Control of the straits determined whether food shipments could reach the city. Naval engagements in these waters were not peripheral skirmishes but existential contests. The Spartan victory at Aegospotami in 405 BCE, achieved under Lysander’s command, effectively severed Athenian access to its grain lifeline. Without secure sea lanes, the urban population of Athens faced immediate vulnerability. Military defeat translated into economic strangulation.

As Spartan naval capacity grew, trade routes adjusted accordingly. Allies and merchants recalibrated toward the emergent power capable of providing maritime security. Networks reorganize around protection. Once Sparta demonstrated the ability to protect shipping and punish resistance, economic flows followed that capacity. This reorganization was gradual but cumulative. It did not require universal loyalty to Sparta; it required sufficient confidence that Athenian protection was no longer exclusive or reliable.

The reconfiguration of maritime routes illustrates a broader principle about imperial systems and economic interdependence. Economic centrality is sustained not simply by production or geography but by enforcement capability and perceived stability. When enforcement becomes uncertain, peripheral actors hedge by diversifying trade relationships and adjusting their risk exposure. In the Aegean, this meant accommodating Spartan fleets and recalibrating tribute obligations, port access, and diplomatic alignments. The shift was not instantaneous, nor was it driven by ideological conversion. It reflected pragmatic adaptation to a changing security environment. Merchants and allied states alike calculated which power could guarantee safe passage, predictable exchange, and protection from piracy or interdiction. Economic survival incentivized alignment with the authority best positioned to secure sea lanes, even if that authority had previously been a rival.

By 404 BCE, the cumulative effect of naval defeats, alliance defections, and disrupted trade routes had hollowed out Athenian resilience in ways that extended far beyond battlefield losses. The siege that ended the war was as much an economic culmination as a military one. Athens surrendered not solely because it lacked ships but because it lacked access to the networks that sustained its urban population and imperial infrastructure. The Peloponnesian War demonstrates that naval power underwrites economic architecture, and when that power falters, networks reorganize with striking speed. Maritime empires depend upon uninterrupted circulation of goods, resources, and confidence. Once circulation shifts and alternative protections emerge, centrality dissolves. The collapse of Athenian dominance was not only a military defeat but a reordering of the interconnected systems upon which its power had depended.

The Structural Lesson: Indispensability Is a Political Fiction

The collapse of Athenian maritime dominance after 413 BCE reveals a structural truth about interstate systems: indispensability is rarely an objective condition and more often a political narrative sustained by performance. Athens believed that its naval power, tribute network, and commercial centrality rendered it irreplaceable within the Aegean order. That belief was reinforced by decades of success, institutional integration, and the absence of a rival capable of matching its maritime reach. Yet indispensability depended not on geography, resources, or past victories alone but on continued credibility in the present. Once that credibility weakened, the assumption of irreplaceability dissolved with remarkable speed. Power that appears permanent under conditions of stability can prove conditional under stress. The Athenian experience demonstrates that dominance is sustained less by static advantage than by the ongoing perception that no viable alternative exists.

Imperial systems function through signaling. Military deployments, fiscal extraction, alliance management, and diplomatic posture all communicate expectations about durability. Allies align not only because of coercion or shared ideology but because they judge the central power likely to endure. When signals shift from strength to uncertainty, subordinate actors reassess. Hedging becomes rational. Realignment becomes plausible. The Athenian case illustrates that even a dominant naval empire can be perceived as replaceable once rivals demonstrate credible alternatives. Indispensability is relational, not intrinsic.

This lesson extends beyond ancient Greece and applies to the broader mechanics of power in networked systems. Political orders rely on belief in central reliability, predictability, and long-term capacity. If that belief erodes, networked systems reorganize around emerging nodes of security and economic stability. The process does not require ideological hostility toward the dominant power. It requires uncertainty about its future trajectory. In Athens’ case, the revolts of 413–411 BCE were not primarily moral judgments on imperial conduct. They were recalculations prompted by altered risk environments. When central authority appears extractive, overstretched, or unpredictable, actors diversify commitments to reduce vulnerability. The appearance of credible alternatives accelerates this diversification, transforming caution into structural shift.

The fiction of indispensability persists because success encourages overconfidence. Dominant powers often mistake accumulated influence for structural permanence. Yet permanence depends upon continual maintenance of trust, security, and credible enforcement. Athens discovered that its empire endured not because it was uniquely necessary but because it had successfully convinced others that alternatives were too costly. Once alternatives appeared viable, that conviction evaporated. The lesson is not that dominance is impossible, but that dominance without sustained credibility invites reorganization.

Enduring Legacies: Indispensability and American Centrality in the Trump Era

Assertions of American indispensability have long been embedded in U.S. foreign policy rhetoric, but they have taken on renewed emphasis during the presidency of Donald Trump. Framed through the language of economic nationalism and strategic leverage, the argument holds that global prosperity and security remain fundamentally dependent upon American markets, military capacity, and financial systems. Trade deficits are portrayed as evidence that partners relied disproportionately on U.S. consumption, and tariffs are introduced as tools to compel renegotiation of existing arrangements. The premise is clear: because the United States occupied a central position in global trade and finance, it possessed unique leverage that others could not easily circumvent.

Such reasoning parallels the structural assumption Athens made. In both cases, centrality was treated as durable and alternatives as prohibitively costly. Yet modern economic networks are diffuse and adaptive. While the United States remains a dominant economy, global supply chains have diversified over decades. Regional trade agreements, currency arrangements, and security partnerships create multiple nodes of interaction. When pressure is applied through tariffs or threats of withdrawal from multilateral institutions, partner states respond by exploring hedging strategies. These may include negotiating new trade pacts, expanding ties with other major powers, or investing in domestic capacity to reduce dependence.

Hedging in the contemporary system does not necessarily signal hostility toward the United States. Rather, it reflects risk management under conditions of perceived unpredictability. If allies question the durability of U.S. commitments to trade frameworks or security guarantees, they may diversify partnerships to reduce exposure. Economic centrality, like naval dominance in the Aegean, depends on confidence in sustained engagement. When confidence wavers, diversification becomes rational. The process is gradual and often understated, but it can reshape patterns of alignment and commerce.

The comparison does not imply equivalence between ancient Athens and the modern United States, nor does it predict imminent systemic collapse. The United States commands resources and institutional influence far exceeding those of classical city-states. The structural lesson, however, remains consistent. Indispensability is not a fixed attribute but a condition maintained through credibility, predictability, and reciprocal benefit. When dominant powers assume that partners lack viable alternatives, they risk accelerating the search for those alternatives. Networked systems reorganize in response to signals. Centrality persists only so long as others perceive it as stable and mutually advantageous.

Conclusion: After Sicily, the Empire Was Already Replaced

The final surrender of Athens in 404 BCE is often treated as the decisive end of the Peloponnesian War, marked by the dismantling of the Long Walls and the imposition of Spartan terms. Yet the true turning point had occurred more than a decade earlier. After the Expedition, the structural foundations of Athenian dominance had already begun to erode. Military losses were catastrophic, but the deeper rupture lay in perception. Once allies concluded that Athens could be resisted and replaced, the empire’s cohesion shifted from inevitability to contingency. The outward forms of control persisted for a time, but the logic sustaining them had weakened.

Empires rarely collapse in a single moment. They unravel as networks reorient. The revolts of 413–411 BCE, the infusion of Persian gold into Spartan naval construction, and the gradual redirection of trade routes were not isolated developments. They were components of systemic reorganization. By the time of Aegospotami, much of the Aegean had already recalibrated. Athens continued to fight, but it fought within a landscape that had been quietly reordered. The decisive naval defeat confirmed a transformation that had long been underway.

The lesson is neither fatalistic nor narrowly historical. Dominance depends upon sustained credibility, and credibility depends upon performance that reassures allies of continuity and reliability. When central powers assume permanence, they risk overlooking subtle shifts in alliance behavior that accumulate beneath the surface. Hedging does not announce itself as revolution. It begins as diversification, contingency planning, parallel agreements, and incremental realignment. These actions are often defensive rather than aggressive, framed as insurance rather than rebellion. But they eventually alter the architecture of the system. Trade routes shift. Diplomatic commitments multiply. Financial backing moves toward alternative centers. What once appeared as peripheral adjustments becomes structural change. Athens’ fall illustrates how quickly centrality can become conditional once alternatives gain plausibility, and how difficult it is to reverse realignment once confidence has migrated elsewhere.

After Sicily, the empire was already being replaced, not because Sparta immediately surpassed Athens in every dimension, but because the belief in Athenian indispensability fractured. Once that belief dissolved, loyalty followed interest rather than habit. The Peloponnesian War offers a structural reminder: power is sustained not only by force but by confidence in its durability. When that confidence wanes, networks reorganize, and what once appeared indispensable becomes one node among many.

Bibliography

- Allison, Graham. Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

- Dover, K. J. “Thucydides’ Historical Judgment: Athens and Sicily.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 81C (1981), 231-238.

- Hornblower, Simon. The Greek World 479–323 BC. 4th ed. London: Routledge, 2011.

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook (various years).

- Kagan, Donald. The Fall of the Athenian Empire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987.

- —-. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Random House, 1987.

- Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye Jr. Power and Interdependence. 4th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2011.

- Lebow, Richard Ned and Robert Kelly. “Thucydides and hegemony: Athens and the United States.” Review of International Studies 27 (2001), 593-609.

- Meiggs, Russell. The Athenian Empire. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.

- Office of the United States Trade Representative. Annual Reports (2017–2025).

- Rhodes, P. J. A History of the Classical Greek World, 478–323 BC. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Rex Warner. Revised by M.I. Finley. London: Penguin Classics, 1972.

- Tian, Zimo. “Interpreting Athenian Statecraft: The Delian League.” The European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 4 (2024), 11-21.

- West, Allen Brown. “The Tribute Lists and the Non-Tributary Members of the Delian League.” The American Historical Review 35:2 (1930), 267-275.

- Xenophon. Hellenica. Translated by Carleton L. Brownson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1918.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.16.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.