The Maya collapse was the outcome of environmental stress interacting with political structures organized around visible legitimacy and sacred continuity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Collapse and the Politics of Recognition

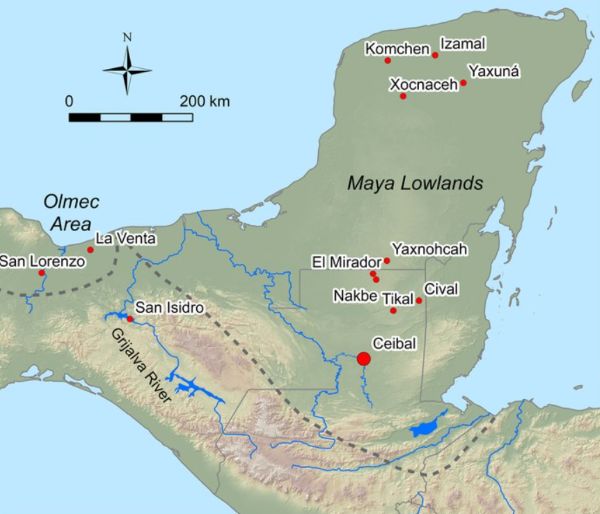

The collapse of the Classic Maya civilization between approximately 800 and 900 CE remains one of the most intensively studied transformations in pre-Columbian history. Monumental centers across the southern lowlands, including Tikal, Copán, Palenque, and Caracol, experienced demographic decline, cessation of monument dedication, and eventual abandonment. The carved stelae that once marked dynastic continuity fell silent. Royal inscriptions, which had meticulously recorded accessions and ritual cycles for centuries, ceased in many regions within a remarkably compressed timeframe. The phenomenon was neither instantaneous nor uniform. Some regions contracted earlier than others; some northern centers persisted or reoriented toward new political and economic configurations. Yet the broader pattern is unmistakable: the political, ceremonial, and demographic systems that had defined Maya urban life fragmented within the span of several generations. The scale and speed of this transformation have generated decades of debate concerning causation, forcing scholars to reconsider the relationship between environment, political authority, and societal resilience.

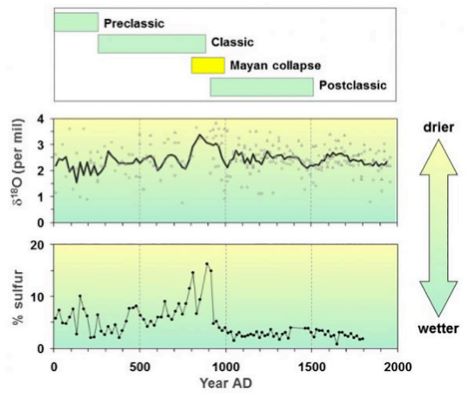

Earlier explanations emphasized warfare, peasant revolt, foreign invasion, or simple political exhaustion. While each of these factors contributed in varying degrees, paleoclimatic research has significantly reframed the discussion. High-resolution sediment cores and isotopic data from lakes and caves in the Yucatán Peninsula indicate repeated and severe drought episodes during the Terminal Classic period. These drought cycles coincided with already intensifying pressures from deforestation, soil depletion, and population density in ecologically marginal zones. The environmental context of collapse is no longer speculative. The question is not whether climatic stress occurred, but how political systems responded to its intensification.

The Classic Maya collapse illustrates a politics of recognition failure. Environmental signals were materially visible: reservoirs diminished, seasonal rainfall became unreliable, crop yields faltered, and landscapes altered under sustained deforestation for agriculture and lime plaster production. Archaeological evidence points to increasing strain on water storage systems and agricultural terraces even before the final cessation of monumental activity. Yet despite these pressures, elite investment in monument construction, ritual display, and dynastic inscription continued well into periods of mounting ecological stress. Massive temple complexes were expanded, new stelae erected, and elaborate calendrical rituals performed. Rather than pivoting toward systemic reorganization of resource management at scale, Maya rulers appear to have reinforced the symbolic architecture of legitimacy. Ritual intensified even as rainfall diminished. Prestige systems persisted even as ecological thresholds narrowed. The material and symbolic dimensions of society moved in divergent directions, revealing a tension between environmental constraint and political self-presentation.

Collapse is not understood here as drought acting upon passive society. It emerges from the interaction between environmental stress and elite decision-making structured around legitimacy maintenance. The decisive variable becomes recognition: whether leadership interprets crisis as temporary fluctuation or structural transformation. The Maya case suggests that symbolic reassurance can stabilize authority in the short term while accelerating vulnerability in the long term. When ecological thresholds are crossed, ritual cannot substitute for rain, and legitimacy performance cannot replenish exhausted soils. The politics of recognition becomes central to understanding how environmental limits translate into civilizational contraction.

Ecological Foundations: Rainforest Agriculture and Fragile Abundance

Maya civilization flourished in an environment that appeared abundant but was ecologically complex and inherently fragile. The tropical lowlands of Mesoamerica supported dense populations through a combination of intensive agriculture, water management, and landscape modification. Contrary to earlier assumptions that Maya subsistence depended solely on shifting slash-and-burn cultivation, archaeological research demonstrates a sophisticated array of agricultural strategies. These included raised fields in wetlands, terraced hillsides, household gardens, and managed forest systems. Urban centers were sustained by intricate relationships between settlement zones and surrounding agricultural hinterlands. Yet this apparent abundance depended upon careful calibration between population density, soil fertility, and rainfall reliability.

Rainfall in the Maya lowlands was seasonal and variable, concentrated during specific months of the year. Unlike societies dependent on large perennial rivers, the Maya relied heavily on rain-fed agriculture supplemented by reservoirs and artificial water storage systems. Urban centers such as Tikal constructed extensive reservoir networks designed to capture and retain seasonal rainfall. These systems required continual maintenance and sufficient precipitation to function effectively. When rainfall patterns became erratic or reduced over multiple years, water storage capacity alone could not fully compensate. Agricultural productivity in upland and marginal zones was particularly sensitive to even modest shifts in precipitation.

Compounding climatic vulnerability was the ecological cost of monumental construction and population growth. The production of lime plaster for temples, plazas, and elite residences required large quantities of wood to fuel kilns capable of reaching high temperatures. This demand contributed to sustained deforestation around major urban centers, reducing canopy cover that had previously stabilized soils and moderated local microclimates. Deforestation altered hydrological cycles by diminishing evapotranspiration and increasing surface runoff, which in turn intensified soil erosion during heavy rains. Terraced hillsides, while ingenious adaptations, were vulnerable to collapse if maintenance lapsed or vegetation buffers declined. At the same time, population expansion increased pressure to cultivate marginal lands, shortening fallow cycles and reducing opportunities for soil regeneration. Intensive maize production gradually depleted nutrients, particularly when combined with erosion from cleared slopes. What had once been adaptive intensification, enabling demographic growth and architectural grandeur, risked becoming ecological overshoot when repeated drought stress compounded declining soil fertility and reduced forest resilience.

The scale of Maya urbanism rested upon a delicate balance. Intensive agricultural innovation allowed cities to flourish in environments lacking major river systems. However, that innovation did not eliminate environmental constraint; it postponed and redistributed it. As population densities increased, more marginal lands were brought under cultivation. Reservoir systems expanded. Labor investment in landscape engineering intensified. Each of these strategies enhanced short-term productivity but narrowed the margin for error in the face of sustained drought. Fragile abundance replaced ecological slack.

Understanding these ecological foundations is essential to interpreting collapse. The Maya did not inhabit an environmentally doomed landscape. They engineered remarkable adaptations that supported centuries of political and cultural florescence. Yet those adaptations were contingent upon rainfall stability and sustainable land use. When repeated drought cycles intersected with deforestation and soil degradation, the agricultural base that underwrote elite authority and monumental display became increasingly strained. The environment did not abruptly fail; it gradually tightened the constraints within which political systems operated. In that tightening, vulnerability became structural.

Drought Cycles and Paleoclimate Evidence

The environmental dimension of the Maya collapse is no longer speculative. Over the past three decades, paleoclimatic research has produced high-resolution datasets that reconstruct rainfall variability in the Maya lowlands with increasing precision. These findings have shifted the debate from whether drought occurred to how prolonged and severe it was, and how closely it corresponded with political fragmentation. Rather than a single catastrophic event, the evidence points toward repeated drought cycles during the Terminal Classic period, layered atop existing ecological strain.

One of the most influential datasets comes from sediment cores extracted from Lake Chichancanab in the northern Yucatán Peninsula. Isotopic analysis of gypsum deposits indicates significant reductions in precipitation during the ninth century CE. These reductions were not minor fluctuations within normal variability. They suggest sustained dry intervals that would have substantially diminished surface water availability. Because much of the Maya lowlands lacked perennial rivers, even modest decreases in rainfall could have had outsized consequences for reservoir-dependent cities. The Lake Chichancanab record aligns chronologically with the decline of major southern lowland centers.

Speleothem records from caves in Belize and the Yucatán provide independent confirmation of prolonged aridity. Oxygen isotope ratios preserved in cave formations reflect changes in rainfall patterns, allowing researchers to reconstruct precipitation variability at decadal resolution. These records indicate multi-year and multi-decade drought episodes between approximately 800 and 930 CE, with particularly severe dry intervals clustering in the ninth century. The significance of these findings lies not simply in their severity but in their recurrence. Maya society had endured seasonal variability for centuries, developing reservoirs and agricultural diversification strategies to buffer short-term stress. What distinguishes the Terminal Classic period is the compression of repeated drought intervals within a limited historical window. Recovery between episodes appears to have been partial and short-lived, limiting the opportunity for soil regeneration, forest regrowth, and reservoir replenishment. As each successive drought struck, the cumulative ecological burden increased, transforming what might have been manageable fluctuation into systemic destabilization.

Recent interdisciplinary studies have further correlated climatic data with archaeological timelines of political decline. Analyses combining speleothem records, lake sediments, and hieroglyphic chronologies reveal that major episodes of monument cessation and dynastic disruption align closely with drought peaks. While correlation does not establish singular causation, the temporal convergence strengthens the argument that environmental stress played a central role in destabilizing political systems. The collapse of centers such as Copán and Tikal occurred within the same broad climatic downturn documented in paleoclimate proxies.

The scale and duration of drought matter more than the mere presence of aridity. Short-term dry spells can be buffered through storage, trade, or temporary migration. Multi-decade drought cycles, particularly when interspersed with only partial recovery, erode agricultural resilience. Reservoirs diminish, soil moisture declines, and food surpluses shrink. In densely populated urban centers dependent upon elaborate water management systems, repeated rainfall deficits could produce cascading effects: food shortages, social unrest, and intensified competition among rival polities. Environmental pressure compounded political fragmentation already underway.

The paleoclimate evidence does not reduce the Maya collapse to climate determinism. Rather, it clarifies the environmental context within which political decisions were made and constraints tightened. The repeated drought cycles of the ninth century CE narrowed the margin for adaptive error, particularly in landscapes already stressed by deforestation and soil exhaustion. These climatic downturns did not occur in isolation but interacted with warfare, demographic pressure, and elite competition to produce cumulative strain. The decisive question is not whether drought alone destroyed Maya civilization, but whether leadership recognized the structural implications of repeated climatic disruption and adjusted accordingly. The data suggest that environmental signals intensified over decades, gradually transforming rainfall variability into persistent aridity. How elites interpreted and responded to those signals, whether as temporary hardship or structural shift, shaped the trajectory from stress to fragmentation.

Elite Monumentalism and the Reinforcement of Legitimacy

Maya political authority was inseparable from spectacle. Divine kingship rested upon the visible performance of ritual, calendrical mastery, and architectural grandeur. Stelae carved with hieroglyphic inscriptions recorded dynastic accessions, military victories, and ritual events tied to sacred time cycles. Temples rose above plazas as embodiments of cosmic order, linking rulers to gods and ancestors. Monumental construction was not ornamental excess; it was the material language of legitimacy. In such a system, authority required continual reaffirmation through public display.

Archaeological evidence indicates that monument dedication and temple expansion continued during periods when paleoclimate data suggest mounting drought stress. At several major centers, rulers erected new stelae and commissioned elaborate architectural projects deep into the ninth century CE. These investments required labor mobilization, quarrying, plaster production, and coordinated planning, all of which depended on functioning administrative structures. The persistence of monumentalism suggests that elites did not immediately curtail prestige expenditures in response to environmental strain. Instead, symbolic production remained central to political life even as agricultural foundations weakened.

The production of lime plaster for monumental architecture carried ecological consequences. Lime manufacture demanded large quantities of wood to fuel kilns, intensifying deforestation around urban cores. In a tropical ecosystem already sensitive to seasonal rainfall variability, sustained forest clearance altered local microclimates and reduced evapotranspiration, potentially diminishing localized rainfall retention. Deforestation exposed thin tropical soils to erosion, particularly during heavy seasonal downpours that followed drought intervals. As canopy cover declined, water runoff increased, carrying nutrient-rich topsoil away from cultivated fields and terraces. The environmental cost of monumental display was cumulative rather than immediate. In a context of repeated drought cycles, continued architectural expansion may have compounded hydrological instability and agricultural vulnerability. Monumental construction represented not only political assertion but also ecological burden. The paradox is striking: as resilience narrowed, elite investment in visible legitimacy may have accelerated the environmental degradation that intensified crisis.

Ritual intensification may have functioned as reassurance amid uncertainty. In Maya cosmology, rulers mediated between human communities and divine forces believed to govern rainfall, fertility, and cosmic balance. Drought was not simply meteorological misfortune; it could be interpreted as disruption in sacred reciprocity between rulers, ancestors, and deities. Public ceremonies, bloodletting rites, and calendrical commemorations reaffirmed the ruler’s role as guarantor of order and intercessor for agricultural renewal. Intensified ritual performance could be understood as an effort to restore cosmic equilibrium in the face of climatic instability. Rather than signaling denial in a modern psychological sense, continued ritual display may have represented a culturally coherent response to ecological stress. Yet coherence within symbolic systems does not necessarily generate material adaptation at scale. Ritual could reaffirm meaning and authority without restructuring water management, land use, or inter-polity coordination. The symbolic reaffirmation of legitimacy may have strengthened short-term political stability even as environmental limits tightened.

Political competition among city-states further reinforced the incentive to maintain monumental activity. Maya polities operated within a landscape of rival courts and shifting alliances. Monument erection and architectural expansion signaled strength to allies and adversaries alike. To curtail display risked appearing weakened. In such an environment, even leaders aware of environmental strain faced structural pressure to sustain visible prestige. Legitimacy was not abstract; it was publicly carved in stone. The cost of symbolic retreat could be immediate political vulnerability.

The cumulative effect of sustained monumentalism during ecological contraction was a widening gap between symbolic continuity and material constraint. Elites reaffirmed dynastic permanence at the very moment that rainfall variability and soil exhaustion undermined agricultural stability. Monumental inscriptions projected order even as demographic decline accelerated in some regions. This disjunction does not imply ignorance of hardship. It reflects a political system in which legitimacy was inseparable from spectacle. When environmental thresholds are crossed, however, ritual affirmation cannot replenish reservoirs or restore exhausted soils. Monumental persistence becomes a revealing index of how leadership prioritized symbolic reinforcement over structural reorganization during periods of intensifying stress.

Symbolic Reassurance versus Structural Adaptation

The persistence of monumentalism during the Terminal Classic period raises a broader question about institutional response. When ecological stress intensifies, political systems can pursue two general strategies: structural adaptation or symbolic reassurance. Structural adaptation requires reorganizing resource management, recalibrating economic expectations, and potentially altering patterns of settlement and authority. Symbolic reassurance, by contrast, seeks to stabilize legitimacy through continuity of ritual, narrative, and visible order. The archaeological record of the Maya suggests that the latter strategy predominated at many major centers during periods of repeated drought.

Evidence for large-scale, coordinated environmental reform across multiple Maya polities during the ninth century CE remains limited. While individual cities invested in reservoirs, terraces, and water management features, there is little indication of sustained inter-polity collaboration aimed at systemic ecological restructuring. Instead, hieroglyphic records from the period reveal intensifying warfare, shifting alliances, and competitive monument dedication. Rather than pooling resources to mitigate shared environmental stress, rival courts often appear to have doubled down on displays of dynastic continuity. The political landscape fragmented even as environmental constraints tightened.

Symbolic reassurance offered short-term advantages. Monumental rituals reaffirmed the ruler’s divine mandate, reinforcing social cohesion during uncertainty. Public ceremonies and calendrical observances maintained a sense of cosmic stability even as rainfall faltered. For elites whose authority rested upon sacred kingship, acknowledging structural ecological limits carried political risk. To concede that rainfall patterns had shifted beyond ritual remedy would undermine the theological foundations of rule. Continuity of spectacle functioned as both political strategy and cosmological obligation.

Yet symbolic continuity cannot substitute indefinitely for material adaptation. As repeated drought cycles eroded agricultural productivity and reservoirs diminished, the capacity of ritual performance to sustain demographic and economic stability narrowed. Without systemic recalibration of land use, inter-polity cooperation, or population distribution, reassurance became increasingly disconnected from ecological reality. The Maya case demonstrates that when leadership privileges legitimacy maintenance over structural redesign, environmental stress accumulates into political fragmentation. The choice is not between ritual and reform in absolute terms, but between symbolic reinforcement alone and adaptation proportionate to ecological transformation. When the former predominates, resilience contracts.

Political Fragmentation and Urban Abandonment

By the late ninth century CE, the cumulative pressures of drought, ecological degradation, and intensified political competition manifested in visible fragmentation across the southern lowlands. Monument erection declined sharply in many major centers. Hieroglyphic inscriptions that had once recorded orderly dynastic succession ceased altogether at sites such as Copán and Tikal. The political vocabulary of permanence fell silent. This cessation does not signal instantaneous collapse, but it marks the unraveling of centralized authority that had defined Maya kingship for centuries. Power did not vanish; it fractured.

Urban abandonment unfolded unevenly across the region. Archaeological evidence indicates population decline, reduced construction activity, and eventual desertion at numerous southern lowland centers. Residential compounds were left unmaintained, ceremonial cores fell into disuse, and once-bustling plazas became overgrown. Household archaeology suggests gradual depopulation rather than sudden flight, with some compounds showing evidence of partial occupation before complete abandonment. Agricultural terraces fell out of repair, and reservoir systems accumulated sediment without systematic dredging. The process likely occurred over generations, as households relocated in stages in response to declining food security, political instability, and diminishing ritual authority. Migration may have followed kinship networks or trade corridors toward regions with more reliable rainfall or emerging political centers. Abandonment was not a singular catastrophic moment but an extended withdrawal from urban density under conditions that no longer sustained concentrated settlement.

Political fragmentation accompanied demographic contraction. As major dynasties weakened or disappeared, regional power centers shifted in complex and uneven ways. Some polities intensified warfare, perhaps competing for shrinking agricultural hinterlands or seeking to capture symbolic capital through conquest narratives. Hieroglyphic records from the late eighth and early ninth centuries suggest episodes of conflict that may have compounded ecological stress by disrupting trade and agricultural cycles. Other centers appear to have reoriented economically and politically, adjusting to altered demographic landscapes. Northern centers such as Chichén Itzá and later Mayapán rose to prominence, indicating that political vitality did not vanish but relocated. This geographic reconfiguration underscores that collapse in the southern lowlands did not equate to the disappearance of Maya civilization as a whole. Rather, the distribution of authority and population shifted toward regions better positioned to navigate evolving environmental and economic constraints.

The breakdown of inter-polity networks further eroded stability. Trade routes that had connected distant centers for the exchange of obsidian, jade, cacao, and other goods diminished in scale or altered direction. Diplomatic marriages and ritual alliances that once reinforced regional cohesion appear less frequently in the record. Fragmentation extended beyond urban cores into the broader web of economic and symbolic relationships. As coordination weakened, resilience declined. Environmental stress interacted with political decentralization to produce cascading effects that neither ritual performance nor military assertion could reverse.

The Classic Maya collapse represents contraction rather than annihilation. Urban density thinned, monumental programs ceased in many regions, and centralized dynastic authority fractured. Yet Maya communities persisted, adapting to new political configurations and landscapes. The southern lowlands did not empty entirely, nor did cultural knowledge vanish. What collapsed was the scale and integration of Maya urban civilization. Political fragmentation and urban abandonment were not simply consequences of drought; they were the structural outcomes of a system that failed to recalibrate as ecological thresholds narrowed. Collapse marked the end of a particular political form, not the end of a people.

Enduring Patterns: Climate Warning, Elite Denial, and Modern Structural Risk

The Maya collapse offers more than a regional case study of environmental stress. It reveals a structural pattern that recurs when ecological warning signals intensify but political systems respond primarily through symbolic reinforcement. The Maya elites did not lack evidence of drought. Reservoir levels fell, agricultural yields declined, and demographic pressures mounted. Yet leadership invested heavily in reaffirming legitimacy through monument dedication, ritual display, and dynastic continuity. The environmental signals were visible, but their structural implications were not fully translated into systemic redesign. The pattern is not one of ignorance, but of prioritization.

Modern societies possess scientific tools unavailable to ancient polities. Atmospheric monitoring networks measure greenhouse gas concentrations with extraordinary precision. Satellite systems track deforestation, ice sheet loss, ocean heat content, and changing precipitation regimes in real time. Climate models integrate physical, chemical, and biological data to project future warming trajectories under different emissions scenarios. International assessment bodies synthesize these findings into consensus reports that articulate degrees of confidence and projected impacts. Reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change draw upon thousands of peer-reviewed studies documenting anthropogenic warming, intensifying heatwaves, hydrological disruption, and rising sea levels. The informational environment, taken collectively, is not ambiguous. Yet recognition at the level of data does not automatically produce institutional transformation. Economic systems built upon fossil fuel dependency, infrastructure designed for historical climate baselines, and political cycles oriented toward short-term electoral horizons complicate structural adaptation. Awareness can coexist with delay when structural transition threatens entrenched economic interests or political coalitions.

Climate denial does not always take the form of outright rejection of scientific evidence. It can manifest as deferral, reframing, or prioritization of immediate economic concerns over long-term ecological thresholds. Political leaders may emphasize growth, national competitiveness, or technological optimism while postponing large-scale structural transition. Public messaging can reassure constituencies that disruption is manageable, cyclical, or exaggerated. The result is a familiar disjunction between visible environmental signals and systemic redesign. Like Maya monumentalism amid drought, modern political rhetoric can reinforce legitimacy without altering underlying vulnerability.

The structural risk emerges from temporal compression. Climate systems operate over decades and centuries, yet infrastructure investment and policy delay accumulate consequences that persist long after electoral cycles conclude. Energy grids, transportation networks, urban zoning decisions, and agricultural subsidies shape emissions and vulnerability patterns for generations. Reservoirs in the Maya lowlands diminished gradually before urban abandonment accelerated; ecological deterioration did not occur overnight. Similarly, contemporary thresholds such as coral reef collapse, glacier retreat, or permafrost thaw may unfold incrementally before crossing tipping points that trigger rapid and difficult-to-reverse change. When adaptation is calibrated to short-term variability rather than structural transformation, the margin for effective mitigation narrows. Each year of postponed transition increases the scale of future adjustment required. Recognition delayed can convert manageable transition into crisis management, where options are constrained and costs multiply.

The enduring lesson is not that modern states are destined to replicate ancient outcomes. Institutional capacities, technological innovation, and global coordination mechanisms distinguish contemporary society from the Maya world. Yet the underlying challenge of political cognition remains. Environmental warnings can be empirically clear while institutionally contested or strategically deferred. Leadership that prioritizes symbolic reassurance over structural adjustment may preserve legitimacy in the present while constraining resilience in the future. The Maya case demonstrates that ecological thresholds do not announce themselves with singular dramatic events. They accumulate quietly. The decisive variable is whether governance adapts before environmental constraint renders reform insufficient.

Conclusion: When Ritual Cannot Replace Rain

The Maya collapse was not the inevitable consequence of drought alone. It was the outcome of environmental stress interacting with political structures organized around visible legitimacy and sacred continuity. Repeated drought cycles narrowed agricultural margins, while deforestation and soil exhaustion reduced ecological resilience. Yet elite systems continued to invest in monument construction, ritual affirmation, and dynastic permanence. The environmental signals were not invisible. What faltered was the translation of those signals into structural transformation proportionate to their scale.

The disjunction between symbolic reassurance and material adaptation proved consequential. Monumental inscriptions projected order even as reservoirs declined. Ritual performance reaffirmed divine kingship even as agricultural surpluses contracted. These responses were culturally coherent and politically rational within the logic of Maya sacred authority. They reinforced stability in the short term. The ecological constraints intensified beyond the buffering capacity of spectacle. When rainfall variability became sustained aridity, legitimacy performance could no longer sustain demographic concentration or inter-polity integration.

Collapse did not occur because the Maya failed to innovate. Their agricultural systems, water management strategies, and architectural achievements testify to extraordinary adaptability. What collapsed was a particular scale of political organization dependent upon ecological conditions that shifted beyond its design parameters. Urban density thinned, dynasties ended, and regional power centers relocated. Ritual did not vanish, nor did Maya culture disappear. But ritual could not replace rainfall, and prestige could not regenerate exhausted soils.

The enduring lesson is not fatalistic. Environmental limits do not automatically produce civilizational disappearance. They demand recognition proportionate to transformation. The Classic Maya case demonstrates that when leadership prioritizes symbolic continuity over structural recalibration, vulnerability accumulates quietly. Ecological thresholds are rarely crossed in a single dramatic moment. They tighten gradually, narrowing the space for effective mitigation. When that narrowing reaches a critical point, adaptation becomes contraction. Rain does not respond to ritual. It responds to climate. And political systems that fail to realign with ecological reality eventually relinquish the scale they once sustained.

Bibliography

- Aimers, James J. “What Maya Collapse? Terminal Classic Variation in the Maya Lowlands.” Journal of Archaeological Research 15:4 (2007), 329–377.

- Butzer, Karl W. “Collapse, Environment, and Society.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:10 (2012), 3632–3639.

- Demarest, Arthur A. Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Demarest, Arthur A., Prudence M. Rice, and Don S. Rice, eds. The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2004.

- Dunning, Nicholas, Timothy Beach, and Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach. “Kax and Kol: Collapse and Resilience in Lowland Maya Civilization.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:10 (2012), 3652–3657.

- Haug, Gerald H., et al. “Climate and the Collapse of Maya Civilization.” Science 299:5613 (2003), 1731–1735.

- Houston, Stephen, and David Stuart. “Of Gods, Glyphs, and Kings: Divinity and Rulership among the Classic Maya.” Antiquity 70:268 (1996), 289–312.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report. Geneva: IPCC, 2021.

- Kennett, Douglas J., et al. “Development and Disintegration of Maya Political Systems in Response to Climate Change.” Science 338:6108 (2012), 788–791.

- Medina-Elizalde, Martín, and Eelco J. Rohling. “Collapse of Classic Maya Civilization Related to Modest Reduction in Precipitation.” Science 335:6071 (2012), 956–959.

- Sharer, Robert J., and Loa P. Traxler. The Ancient Maya. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

- Tainter, Joseph A. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Turner, B. L., and Peter D. Harrison, eds. Pulltrouser Swamp: Ancient Maya Habitat, Agriculture, and Settlement in Northern Belize. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983.

- Webster, David. The Fall of the Ancient Maya: Solving the Mystery of the Maya Collapse. London: Thames & Hudson, 2002.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.19.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.