For more than a century, the United States repeatedly approached the threshold of national health care only to retreat into partial solutions.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 did not emerge from a vacuum. It was the product of more than a century of political struggle over whether health care in the United States should be treated as a social right, a market commodity, or a conditional benefit tied to employment, age, or poverty. From the Progressive Era onward, American reformers repeatedly attempted to construct some form of national health insurance, only to see those efforts defeated, narrowed, or redirected into partial systems. The result has been a distinctive trajectory in which the United States built powerful health institutions without ever committing to universal coverage.

That history matters now because the likely unraveling of the ACA’s affordability mechanisms in 2026 is not an aberration. It is the latest manifestation of a structural pattern that has defined American health policy since the early twentieth century. The expiration of enhanced subsidies does not represent the sudden collapse of an otherwise stable system. It exposes the fragility that was built into the law from the outset, a fragility inherited from decades of political compromise, institutional resistance, and ideological contestation.

American health reform has advanced most often through segmentation rather than universality. Hospitals were built before insurance was guaranteed. Coverage for the elderly and the poor arrived decades before coverage for working-age adults. Employer-sponsored insurance became the norm not because it was designed as public policy, but because it emerged accidentally from wartime labor controls and tax incentives. Each of these developments solved a problem while simultaneously narrowing the range of future options. Over time, partial solutions hardened into durable structures, making comprehensive reform increasingly difficult to achieve.

The ACA itself reflected this history. Rather than establishing a national health care system, it sought to expand access within an existing market framework through mandates, subsidies, and regulated exchanges. It succeeded in reducing the uninsured rate and stabilizing coverage for millions, yet it left intact the underlying fragmentation of American health care. Its reliance on subsidies as the primary affordability mechanism made it especially vulnerable to political exhaustion. When those subsidies are treated as temporary, their expiration functions not as a technical adjustment but as a de facto retreat from coverage expansion.

What follows argues that the current moment marks not the failure of a single law, but the reassertion of a long-standing American pattern. For more than a century, national health care has been proposed, deferred, diluted, and redirected. Each attempt left behind institutional residues that shaped what followed. The likely erosion of the ACA should therefore be understood not as the end of reform, but as evidence of how incrementalism, when repeatedly substituted for permanence, produces instability rather than progress.

By tracing the history of American health care reform from the Progressive Era through the New Deal, the postwar period, the Great Society, the single-payer debates of the 1970s, and the passage of the ACA, I situate the present crisis within a broader historical arc. I seek to explain how the United States arrived at a system that expanded coverage without securing it, and why the question of national health care remains unresolved more than a century after it first entered American political life.

Progressive Origins and the Early Failure of National Health Insurance (1900–1920)

At the turn of the twentieth century, national health insurance entered American political discourse as part of a broader Progressive critique of industrial capitalism. Rapid urbanization, workplace injuries, and the instability of wage labor exposed the limits of private charity and local relief. Reformers increasingly argued that health risks were social hazards rather than individual failings, a view influenced by European social insurance models already operating in Germany and Britain. In this context, health insurance was understood not as medical innovation but as economic protection, a means of stabilizing families whose livelihoods could be destroyed by illness.

Early proposals drew heavily on labor reform movements and public health advocates who linked health security to productivity and social order. Progressive reformers emphasized sickness insurance as a counterpart to workers’ compensation and old-age pensions. Yet these ideas emerged before the federal government had developed strong administrative capacity in social policy. The absence of a centralized welfare infrastructure meant that national health insurance appeared both radical and impractical to many legislators, even as industrial conditions made the problem increasingly visible.

The most prominent political endorsement of national health insurance during this period came from Theodore Roosevelt, who included it in the 1912 platform of the Progressive Party. Roosevelt framed health insurance as a natural extension of social responsibility in an industrial society, aligning it with protections for workers, women, and children. His advocacy lent national visibility to the issue, but it also tied health insurance to a partisan insurgency that frightened conservative voters and entrenched opposition. When the Progressive Party collapsed after the election, national health insurance lost its most powerful champion.

Opposition to early health insurance proposals was swift and multifaceted. Employer groups feared increased labor costs and government intrusion into workplace relations. Physicians, organized through the American Medical Association, worried that insurance would undermine professional autonomy and income by inserting the state into medical decision-making. These concerns were amplified by cultural anxieties about socialism, particularly as European welfare systems were associated in the American imagination with state control rather than social protection. Health insurance thus became entangled in ideological battles that extended far beyond medicine.

By the end of World War I, the moment for early national health insurance had passed. Wartime nationalism and postwar conservatism reframed social reform as a threat rather than a necessity. The failure of Progressive Era health insurance proposals established a durable precedent: health care could be acknowledged as a social problem without being accepted as a collective responsibility. That distinction would shape every subsequent attempt at reform, ensuring that future proposals began from a position of political defensiveness rather than institutional continuity.

The New Deal, Social Security, and the Path Not Taken (1930s)

The economic collapse of the Great Depression fundamentally altered the relationship between the federal government and social welfare, creating conditions that made national health care reform appear newly plausible. Mass unemployment, poverty, and insecurity exposed the inadequacy of local relief and voluntary charity, pushing social policy toward national solutions. Health care costs, already burdensome for working families, became untenable for millions who had lost wages entirely. In this environment, illness was no longer a private misfortune but a collective risk bound tightly to economic survival.

Despite this context, health insurance was deliberately excluded from the Social Security Act of 1935. FDR’s administration recognized the severity of the problem but chose to prioritize retirement pensions and unemployment insurance over medical coverage. This decision reflected political calculation rather than ignorance. Social Security itself faced fierce opposition from business interests and conservative lawmakers, and administration officials feared that adding health insurance would jeopardize the entire bill. Health care was thus postponed in the name of preserving what reformers considered the more politically achievable core of the welfare state.

The exclusion of health insurance had lasting structural consequences. By establishing Social Security without medical coverage, policymakers created a foundational social insurance program that treated income security as a national obligation while leaving health care outside that moral and institutional framework. Once Social Security was enacted, it quickly became politically untouchable. Health insurance, by contrast, remained speculative and contested, lacking both administrative infrastructure and a dedicated funding mechanism. The sequencing mattered. What was omitted at the moment of institutional creation became far harder to add later.

Efforts to reconsider health insurance did not disappear entirely. In 1938, the National Health Conference convened policymakers, medical professionals, and social reformers to assess the nation’s health needs. The conference produced extensive documentation linking public health, access to care, and economic stability. Yet its recommendations carried no legislative force. Without presidential commitment to a specific health insurance proposal, the conference served more as a diagnostic exercise than a catalyst for reform.

Opposition from organized medicine further constrained possibilities. The American Medical Association intensified its resistance during the New Deal years, portraying national health insurance as incompatible with professional independence. These objections resonated in Congress, where lawmakers remained sensitive to accusations of socialized medicine. The climate of economic emergency did not override longstanding ideological boundaries around federal involvement in health care. Instead, it reinforced a pattern in which health reform was acknowledged rhetorically but deferred institutionally.

By the end of the 1930s, the path not taken had hardened into precedent. The New Deal demonstrated that sweeping social policy was possible in the United States, but it also established a welfare state built without universal health care. This omission was not a temporary oversight. It shaped the terrain on which all later reform efforts would operate, ensuring that national health insurance would be proposed not as a foundational element of social citizenship, but as an addition to an already settled system.

Universal Coverage Deferred: The Wagner–Murray–Dingell Era (1943–1949)

During World War II and its immediate aftermath, national health insurance reemerged as a serious legislative project rather than an abstract reform ideal. The Wagner–Murray–Dingell bills, introduced repeatedly between 1943 and 1949, proposed universal health insurance financed through the Social Security system. Sponsored by Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York, Senator James E. Murray of Montana, and Representative John Dingell Sr. of Michigan, the legislation sought to normalize health care as a social right, aligning medical protection with retirement and unemployment insurance. Unlike earlier Progressive proposals, these bills were detailed, administratively grounded, and backed by segments of organized labor.

The political environment initially appeared favorable. Wartime mobilization had strengthened the federal state, expanded administrative capacity, and accustomed Americans to national coordination. Labor unions supported the bills as a safeguard for workers and their families, and public opinion polling suggested broad support for government involvement in health care. The proposal framed health insurance as a continuation of wartime solidarity rather than a radical departure from American norms. For a brief period, universal coverage seemed not only imaginable but legislatively achievable.

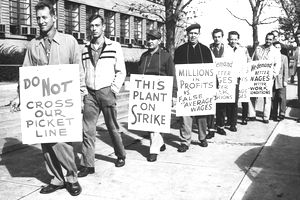

Opposition, however, intensified rapidly. The American Medical Association launched one of the most aggressive lobbying campaigns in its history, denouncing the bills as socialized medicine and warning that federal insurance would undermine the doctor–patient relationship. These arguments gained traction as wartime unity gave way to postwar conservatism. The emerging Cold War climate further stigmatized expansive social policy, allowing opponents to link national health insurance to foreign ideologies. Congressional support eroded as anti-communist rhetoric reshaped political boundaries.

By 1949, the Wagner–Murray–Dingell effort had collapsed. Despite repeated introductions and extensive hearings, the legislation never advanced to passage. Its failure marked a decisive moment. Universal health insurance had been fully articulated, publicly debated, and institutionally plausible, yet it was still rejected. The defeat reinforced a pattern that would recur throughout the twentieth century: comprehensive reform proposals would surface during moments of crisis, only to be deferred once political conditions shifted. National health care remained a recognized need, but one perpetually postponed.

Truman’s National Health Plan and the Limits of Postwar Liberalism

In 1945, Harry S. Truman made national health insurance a central element of his domestic agenda, marking the first time a sitting president explicitly proposed a comprehensive health care program for all Americans. Truman framed health insurance as a natural extension of New Deal principles, arguing that access to medical care was inseparable from economic security and democratic citizenship. His proposal called for a federally administered insurance system covering physician services, hospital care, and preventive medicine, financed through payroll taxes. Unlike earlier legislative efforts, Truman’s plan carried the authority of the executive branch and was presented as a moral imperative rather than a technical reform.

Despite this presidential backing, the plan faced immediate and sustained opposition. Conservative lawmakers condemned it as an overreach of federal power, while the AMA intensified its campaign against what it labeled socialized medicine. In the postwar climate, anxieties about government control and individual freedom resonated strongly, allowing critics to portray national health insurance as incompatible with American values rather than as an extension of social insurance.

The political context further constrained Truman’s efforts. The immediate postwar years were marked by inflation, labor unrest, and the consolidation of Cold War ideology. Anti-communism narrowed the space for expansive social policy, and national health insurance became entangled in broader fears about state authority. Although Truman continued to defend his proposal throughout his presidency, Congress declined to advance it, signaling the limits of postwar liberalism when confronted with organized opposition and ideological polarization.

The failure of Truman’s health plan had lasting implications. It demonstrated that even direct presidential advocacy could not overcome entrenched resistance to universal coverage. At the same time, it reinforced a pattern in which health care reform remained politically marginal despite broad acknowledgment of its necessity. Truman’s defeat did not eliminate the idea of national health insurance, but it confirmed that future reforms would likely proceed through narrower, population-specific programs rather than comprehensive national systems.

Building Infrastructure without Universality: The Hill–Burton Compromise

The defeat of Truman’s national health plan did not end federal involvement in health care. Instead, it redirected reform toward a politically safer alternative: infrastructure. The Hospital Survey and Construction Act of 1946, commonly known as the Hill–Burton Act, committed the federal government to funding hospital construction and modernization across the United States. Framed as a response to wartime shortages and regional disparities in medical facilities, the law expanded physical capacity without addressing the question of who would pay for care once those facilities existed.

Hill–Burton represented a strategic compromise. By investing in bricks and mortar rather than insurance, lawmakers avoided the ideological conflict surrounding national health coverage while still claiming progress on public health. The program dramatically increased the number of hospitals, particularly in rural and underserved areas, and helped modernize American medicine. Yet it did so without establishing any guarantee of access. Patients could reach hospitals that they could not afford, and expanded capacity often translated into higher overall costs rather than broader coverage.

The act also carried significant inequities. Although Hill–Burton included provisions requiring hospitals to provide a “reasonable volume” of free care, enforcement was weak and uneven. In practice, many hospitals continued to exclude Black Americans and other marginalized groups, especially in the Jim Crow South. Federal investment thus reinforced existing social hierarchies even as it expanded medical infrastructure. Access to care remained conditional, shaped by race, income, and geography rather than citizenship.

By separating infrastructure from insurance, Hill–Burton entrenched a structural divide that would persist for decades. The federal government assumed responsibility for building the health system but not for ensuring that all Americans could use it. This division allowed policymakers to claim success while deferring the harder question of universality. In historical terms, Hill–Burton marked a turn away from comprehensive reform toward incremental accommodation, a pattern that would define American health policy through the remainder of the twentieth century.

Medicare and Medicaid: Partial Triumph, Structural Fragmentation (1965)

The passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 marked the most significant expansion of public health coverage in American history. Enacted as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society agenda, the two programs fundamentally altered access to care for the elderly, the disabled, and the poor. For the first time, the federal government assumed direct responsibility for financing medical care for large segments of the population. The achievement was transformative, reducing poverty among the elderly and dramatically increasing access to hospitals and physicians.

Yet Medicare and Medicaid were never intended to establish universal health care. Their design reflected political compromise rather than systemic ambition. Medicare covered Americans aged sixty-five and older regardless of income, while Medicaid targeted low-income individuals through a federal-state partnership. Working-age adults outside these categories remained dependent on employer-sponsored insurance or the private market. Universality was explicitly set aside in favor of programs that lawmakers believed could survive congressional resistance.

The political strategy behind this segmentation was deliberate. By anchoring Medicare to Social Security, reformers framed it as an earned benefit rather than public assistance, insulating it from stigma and political attack. Medicaid, by contrast, was structured as a means-tested program, administered by states and subject to wide variation in eligibility and benefits. This bifurcation preserved political feasibility but institutionalized inequality. Two Americans with identical medical needs could receive radically different care depending on age, income, and location.

The success of Medicare paradoxically weakened momentum for broader reform. Once coverage for the elderly was secured, national health insurance lost urgency for lawmakers whose constituencies were now partially protected. Employer-sponsored insurance continued to expand during this period, further entrenching a fragmented system. Health care became a patchwork of programs rather than a unified national commitment, with each piece defended separately and reformed in isolation.

Medicaid’s structure introduced additional instability. Because it relied on state participation and funding, access to care varied dramatically across the country. States exercised discretion over eligibility thresholds, reimbursement rates, and covered services. This flexibility allowed Medicaid to expand over time but also exposed it to political retrenchment. Coverage became contingent not only on income but on geography, reinforcing regional disparities that persist into the present.

By 1965, the United States had achieved what earlier reformers could not: large-scale public health insurance. Yet it had done so in a way that locked in fragmentation. Medicare and Medicaid solved urgent problems while narrowing the political imagination of what reform could look like. The triumph was real, but it came at the cost of coherence. National health care was no longer an unanswered question. It was a deferred one, postponed by partial success rather than resolved through universality.

The 1970s Single-Payer Moment and Its Collapse

By the early 1970s, the conditions for comprehensive health care reform appeared unusually favorable. Medical costs were rising rapidly, employer-sponsored insurance was showing signs of strain, and public dissatisfaction with access and affordability was growing. Unlike earlier periods, reform proposals now included fully articulated single-payer systems modeled explicitly on national health programs abroad. These plans envisioned universal coverage financed through taxation, replacing the fragmented mix of private insurance and public programs with a unified national system.

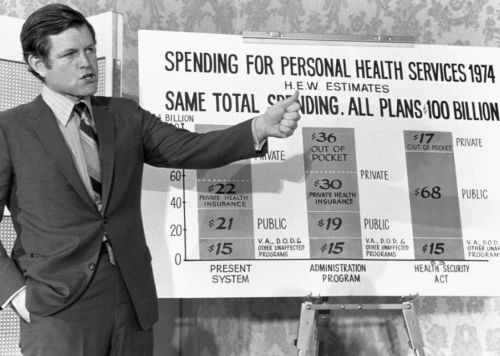

Several prominent proposals emerged during this period, backed by organized labor and progressive legislators. Representative Martha Griffiths introduced legislation supported by the AFL–CIO, while Senator Ted Kennedy championed a national health insurance bill with backing from the United Auto Workers. Extensive congressional hearings were held, generating detailed testimony on costs, administration, and health outcomes. For the first time since the Wagner–Murray–Dingell era, universal health care was treated as a serious legislative option rather than a symbolic aspiration.

Despite this momentum, political fragmentation undermined reform. President Richard Nixon advanced a competing employer-mandate proposal that expanded private coverage rather than replacing it, dividing reform advocates and weakening the case for single payer. At the same time, inflation and economic uncertainty shifted congressional priorities toward cost containment rather than structural transformation. The reform coalition fractured over strategy, with incrementalists and universalists pursuing incompatible goals.

The collapse of the single-payer moment was sealed by the Watergate scandal and its aftermath. Institutional trust eroded, legislative bandwidth narrowed, and ambitious domestic reform became politically toxic. By the mid-1970s, comprehensive health care reform had again receded, replaced by narrower regulatory efforts. The failure was not one of policy design. It was the result of political timing, divided leadership, and a system increasingly resistant to structural overhaul. The opportunity passed, and with it the last best chance for universal health care before the rise of modern market-based reform.

Incrementalism Entrenched: Employer Coverage and Market Reliance

By the late twentieth century, the United States had effectively committed itself to a health care system built around employer-sponsored insurance and regulated markets rather than universal public provision. This arrangement was not the result of deliberate long-term planning, but of accumulated policy decisions that favored incremental expansion over structural reform. Employer coverage, initially a byproduct of wartime wage controls and tax incentives, became the default mechanism for insuring working Americans. Once established, it proved remarkably resilient, shaping both political expectations and institutional constraints.

Employer-sponsored insurance expanded rapidly after World War II, supported by favorable tax treatment that excluded employer contributions from taxable income. This subsidy, larger than any direct health spending program, entrenched private insurance as a cornerstone of the system. For millions of Americans, access to health care became tied to stable employment, reinforcing the perception that coverage was a workplace benefit rather than a social right. Those outside the labor market, including the unemployed, part-time workers, and the self-employed, were left to navigate an unstable individual market.

As medical costs rose in the 1980s and 1990s, policymakers increasingly turned to market-based solutions rather than universal coverage. Managed care, cost-sharing, and consumer choice were promoted as tools to control spending while preserving private insurance. These reforms altered the delivery of care but did not resolve the underlying problem of access. The individual insurance market remained expensive and exclusionary, while employer coverage grew more precarious as firms shifted costs onto workers or dropped benefits altogether.

Incrementalism became the dominant reform logic. Rather than revisiting the question of national health insurance, lawmakers focused on filling gaps through targeted interventions. Programs such as COBRA extended temporary coverage to displaced workers, while the Children’s Health Insurance Program expanded eligibility for low-income children. Each initiative addressed a specific vulnerability without challenging the system’s overall structure. The cumulative effect was a complex mosaic of coverage pathways that differed by age, income, employment status, and state residence.

By the early 2000s, this patchwork had hardened into orthodoxy. Market reliance was no longer framed as a temporary compromise but as a defining feature of American health policy. Universal coverage was increasingly treated as politically unrealistic, even as other industrialized nations consolidated national systems. Incrementalism did not eliminate reform. It constrained it, ensuring that future efforts would operate within a fragmented framework that privileged markets, preserved employer dominance, and left affordability unresolved.

The Affordable Care Act as Compromise, Not Resolution (2010)

The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 represented the most ambitious health care reform since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid, yet it was conceived explicitly as a compromise rather than a definitive solution. The law sought to expand coverage while preserving the existing architecture of American health care, including employer-sponsored insurance and private markets. Rather than replacing fragmented systems, the ACA attempted to regulate and subsidize them, reflecting both political constraint and historical inheritance. Its central aim was not universality in a formal sense, but near-universal access within a market-based framework.

The ACA’s design was shaped by the failures and limits of earlier reform efforts. Lawmakers abandoned single-payer proposals early in the process, concluding that comprehensive public insurance was politically unattainable. Instead, the law relied on an individual mandate to broaden risk pools, income-based subsidies to make private insurance affordable, and state-based exchanges to structure competition. This approach drew heavily from incremental reforms implemented in Massachusetts several years earlier, signaling continuity rather than rupture in American health policy.

From the outset, the ACA faced intense opposition that further narrowed its scope. Legislative negotiations eliminated the public option, a government-run insurance plan that might have introduced competitive pressure into the market. States were granted significant discretion in implementation, most notably through the optional expansion of Medicaid following a Supreme Court decision in 2012. These concessions were necessary for passage, but they entrenched variability and limited the law’s reach, particularly in states that declined to expand coverage.

Despite these constraints, the ACA achieved measurable gains. The uninsured rate fell sharply in the years following implementation, and protections for individuals with preexisting conditions transformed access to care. Young adults gained coverage through parental plans, and preventive services became more widely available. These outcomes demonstrated that incremental reform could produce tangible benefits, even within a fragmented system.

At the same time, the law’s reliance on subsidies exposed a critical vulnerability. Affordability depended on continuous political support for funding mechanisms rather than on permanent institutional guarantees. For middle-income individuals, particularly those purchasing insurance on the exchanges, coverage remained sensitive to premium fluctuations and policy changes. The ACA stabilized access but did not secure it, leaving millions dependent on provisions that could be weakened or withdrawn.

In historical perspective, the ACA stands as both achievement and limit. It expanded coverage further than any previous reform while reaffirming the structural constraints that had long shaped American health care. By choosing compromise over consolidation, the law reflected a century of political accommodation. It addressed immediate crises without resolving the underlying question of whether health care in the United States would ever be treated as a universal social right rather than a conditional benefit.

Repeal by Attrition and the Erosion of Affordability (2017–2026)

Following the Affordable Care Act’s implementation, opposition to the law shifted from failed repeal efforts to strategies aimed at weakening its core mechanisms. Beginning in 2017, congressional Republicans abandoned comprehensive repeal after repeated legislative failures, most notably the collapse of repeal legislation in the Senate. Instead, they pursued incremental measures that altered incentives and destabilized participation. The most consequential of these was the elimination of the individual mandate penalty, which removed a central pillar of the ACA’s risk-balancing framework while leaving the statute formally intact.

Administrative actions further accelerated this process. The Trump administration reduced funding for enrollment outreach, shortened open enrollment periods, and relaxed regulatory enforcement governing insurance markets. These changes did not repeal coverage protections, but they made it harder for eligible individuals to enroll and remain insured. The effects were cumulative rather than dramatic, producing gradual declines in participation that were easily attributed to market behavior rather than policy design. Repeal by attrition proved politically effective precisely because it avoided singular moments of accountability.

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily reversed this erosion. In response to economic disruption and public health emergency, Congress enacted enhanced ACA subsidies through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and later extended them through the Inflation Reduction Act. These measures eliminated the longstanding income cliff and significantly reduced premiums for millions of enrollees. Enrollment reached record highs, confirming that affordability, rather than lack of demand, had been the principal constraint on coverage. The success of these subsidies was widely documented by federal agencies and independent policy analysts.

Yet the enhanced subsidies were never made permanent. Their temporary status reflected both budgetary strategy and political hesitation, preserving flexibility while reintroducing uncertainty. When congressional negotiations in late 2025 failed to extend the subsidies further, their expiration at the start of 2026 marked a turning point. Premiums rose sharply for middle-income households, particularly older adults purchasing insurance on the individual market. Coverage remained legally available, but for many it ceased to be financially viable.

This outcome aligned with long-standing Republican opposition to the ACA and was consistent with the policy posture of Donald Trump, who repeatedly called for the law’s dismantling. What decades of repeal votes and court challenges could not achieve directly was accomplished indirectly through the withdrawal of affordability support. By 2026, the ACA remained on the books, but its capacity to function as a broad coverage expansion had been significantly weakened. The erosion of affordability revealed the law’s central vulnerability: a reliance on political will to sustain access rather than institutional permanence.

The United States in Comparative Perspective

When placed alongside other industrialized nations, the American health care trajectory appears unusual not because of a lack of reform efforts, but because of how those efforts repeatedly stalled short of universality. Countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, and Japan developed national systems through different institutional paths, yet all ultimately established health care as a guaranteed social provision. In each case, reform consolidated rather than fragmented coverage, creating durable systems that expanded incrementally without threatening their core commitment to universality.

The contrast lies less in political imagination than in institutional sequencing. Many countries embedded health care into foundational welfare arrangements during moments of national reconstruction, whether after war, economic collapse, or state formation. Once established, these systems proved difficult to dismantle, even amid ideological shifts. Universal coverage became a baseline rather than a bargaining chip. In the United States, by contrast, health care was consistently postponed while other elements of the welfare state solidified, leaving it perpetually exposed to political reversal.

American exceptionalism in health care is therefore best understood as structural rather than cultural. The United States demonstrated repeated willingness to expand public responsibility in areas such as pensions, disability insurance, and hospital infrastructure. What it failed to do was integrate health care into those commitments at the moment of institutional creation. Each partial reform increased coverage while narrowing the space for comprehensive solutions, producing a system that was expansive yet unstable.

This comparative lens underscores a central irony. The United States did not lack opportunities to establish national health care, nor did it lack public support at key moments. What it lacked was permanence. Other nations treated health care as a settled question once adopted. The American system treated it as perpetually provisional. The likely erosion of the Affordable Care Act’s affordability provisions thus reflects a broader historical pattern, one in which health care remains an unresolved project rather than an established social guarantee.

Conclusion: The Pattern, the Consequence, and the Question Forward

The history traced here reveals a consistent pattern rather than a series of isolated failures. For more than a century, the United States repeatedly approached the threshold of national health care only to retreat into partial solutions. Each moment of reform addressed immediate pressures while leaving the underlying structure intact. Progressive Era proposals introduced the idea of health insurance without institutional follow-through. The New Deal constructed a welfare state that excluded medical care. Postwar liberalism expanded infrastructure and targeted programs while avoiding universality. The Affordable Care Act followed this lineage, extending coverage without securing it as a permanent social guarantee.

Understanding this continuity clarifies the meaning of the current moment. The erosion of the Affordable Care Act’s affordability mechanisms does not represent the collapse of an otherwise stable system. It exposes the vulnerability that has long defined American health policy. When access depends on temporary subsidies rather than permanent institutions, coverage becomes contingent on political cycles rather than social commitment. The likely unraveling of affordability in 2026 reflects not a sudden shift in priorities, but the predictable outcome of a system built on incrementalism and compromise.

This history also complicates narratives of inevitability. The United States did not fail to establish national health care because it lacked ideas, expertise, or public demand. It failed because reform was repeatedly postponed in favor of politically expedient alternatives that narrowed future options. Each partial victory reduced pressure for comprehensive reform while deepening fragmentation. Over time, what began as pragmatism hardened into structural constraint, making universality appear perpetually unrealistic even as other nations treated it as settled policy.

The question forward is therefore not whether the United States has tried to create national health care. The historical record makes clear that it has, repeatedly. The unresolved issue is whether future reform will continue to reproduce the same pattern, addressing crises without consolidating solutions, or whether health care will finally be integrated into the country’s core social institutions. Until that question is answered, American health policy will remain defined less by absence than by deferral, and access to care will continue to reflect the costs of a century-long hesitation.

Bibliography

- Blank, Robert H., and Viola Burau. Comparative Health Policy. 4th ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Blumberg, Linda J., and John Holahan. “Toward Universal Coverage in Massachusetts.” Inquiry 43:2 (2006), 102-121.

- Hacker, Jacob S. The Divided Welfare State: The Battle over Public and Private Social Benefits in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Hoffman, Beatrix. Health Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States since 1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

- Kaiser Family Foundation. “What Happens When Enhanced ACA Subsidies Expire.” https://www.kff.org/.

- Oberlander, Jonathan. The Political Life of Medicare. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Quadagno, Jill. One Nation, Uninsured: Why the U.S. Has No National Health Insurance. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Skocpol, Theda. Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Smith, David Barton. Health Care Divided: Race and Healing a Nation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books, 1982.

- Stevens, Rosemary. In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century. New York: Basic Books, 2025.

- U.S. Congress. American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Public Law 117–2.

- U.S. Congress. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Public Law 117–169.

- U.S. Congress. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111–148, March 23, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.06.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.