Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Gun politics is an area of American politics defined by two primary opposing ideologies about civilian gun ownership. People who advocate for gun control support increasing regulations related to gun ownership; people who advocate for gun rights support decreasing regulations related to gun ownership. These groups often disagree on the interpretation of laws and court cases related to firearms as well as about the effects of firearms regulation on crime and public safety.[1]:7 It is estimated that U.S. civilians own 393 million firearms,[2] and that 35% to 42% of the households in the country have at least one gun.[3][4] The U.S. has the highest estimated number of guns per capita, at 120.5 guns for every 100 people.[5]

The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution reads:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”[6]

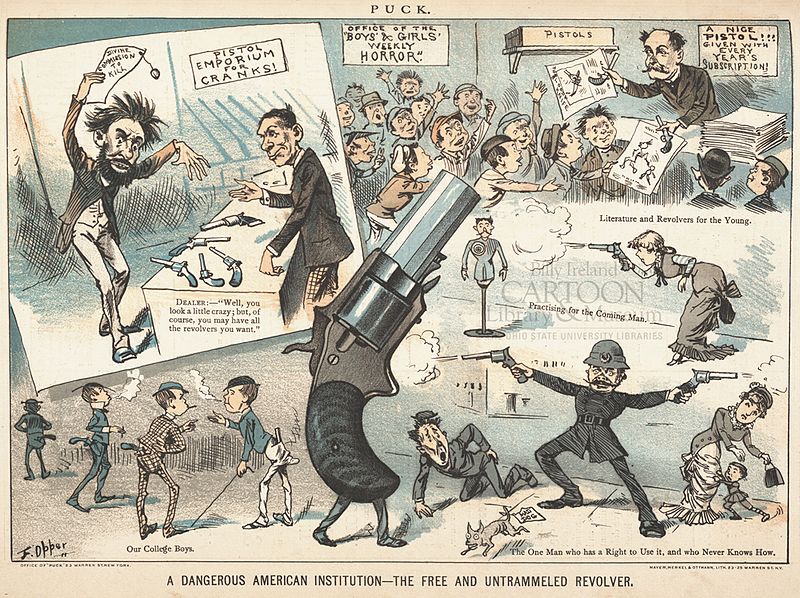

Debates regarding firearm availability and gun violence in the United States have been characterized by concerns about the right to bear arms, such as found in the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and the responsibility of the United States government to serve the needs of its citizens and to prevent crime and deaths. Firearms regulation supporters say that indiscriminate or unrestricted gun rights inhibit the government from fulfilling that responsibility, and causes a safety concern.[7][8][9]:1–3[10] Gun rights supporters promote firearms for self-defense – including security against tyranny, as well as hunting and sporting activities.[11]:96[12] Firearms regulation advocates state that restricting and tracking gun access would result in safer communities, while gun rights advocates state that increased firearm ownership by law-abiding citizens reduces crime and assert that criminals have always had easy access to firearms.[13][14]

Gun legislation, or non-legislation, in the United States, is augmented by judicial interpretations of the Constitution. In 1791, the United States adopted the Second Amendment, and in 1868 adopted the Fourteenth Amendment. The effect of those two amendments on gun politics was the subject of landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2008 (In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the Supreme Court affirmed for the first time that the second amendment guarantees an individual right to possess firearms independent of service in a state militia and to use firearms for traditionally lawful purposes, including self-defense within the home. In so doing, it endorsed the so-called “individual-right” theory of the Second Amendment’s meaning and rejected a rival interpretation, the “collective-right” theory, according to which the amendment protects a collective right of states to maintain militias or an individual right to keep and bear arms in connection with service in a militia.

Historical Background

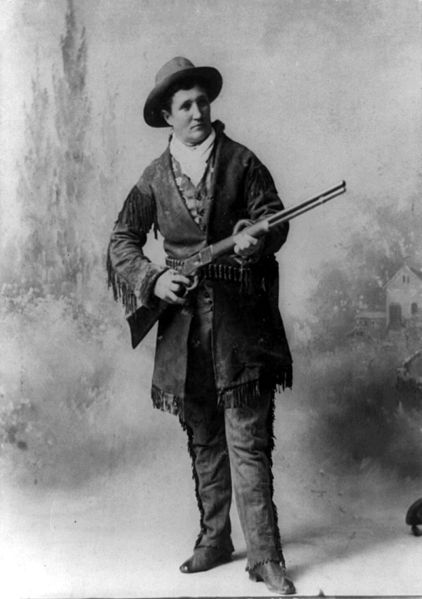

The American hunting tradition comes from a time when the United States was an agrarian, subsistence nation where hunting was a profession for some, an auxiliary source of food for some settlers, and also a deterrence to animal predators. A connection between shooting skills and survival among rural American men, who can buy supplies still today at places like https://huntingmark.com/, was in many cases a necessity and a ‘rite of passage’ for those entering manhood.[1]:9 Today, hunting survives as a central sentimental component of gun culture as a way to control animal populations across the country, regardless of modern trends away from subsistence hunting and rural living.[10]

Prior to the American Revolution, there was neither budget nor manpower nor government desire to maintain a full-time army. Therefore, the armed citizen-soldier carried responsibility. Service in militia, including providing one’s own ammunition and weapons, was mandatory for all men. Yet, as early as the 1790s, the mandatory universal militia duty evolved gradually to voluntary militia units and a reliance on a regular army. Throughout the 19th century the institution of the organized civilian militia began to decline.[1]:10 The unorganized civilian militia, however, still remains even in current U.S. law, consisting of essentially everyone from age 17 to 45, while also including former military officers up to age 64, as codified in 10 U.S.C. § 246.

Closely related to the militia tradition is the frontier tradition, with the need for self-protection pursuant to westward expansion and the extension of the American frontier.[1]:10–11 Though it has not been a necessary part of daily survival for over a century, “generations of Americans continued to embrace and glorify it as a living inheritance—as a permanent ingredient of this nation’s style and culture”.[15]:21

Colonial Era through the Civil War

In the years prior to the American Revolution, the British, in response to the colonists’ unhappiness over increasingly direct control and taxation of the colonies, imposed a gunpowder embargo on the colonies in an attempt to lessen the ability of the colonists to resist British encroachments into what the colonies regarded as local matters. Two direct attempts to disarm the colonial militias fanned what had been a smoldering resentment of British interference into the fires of war.[16]

These two incidents were the attempt to confiscate the cannon of the Concord and Lexington militias, leading to the Battles of Lexington and Concord of April 19, 1775, and the attempt, on April 20, to confiscate militia powder stores in the armory of Williamsburg, Virginia, which led to the Gunpowder Incident and a face-off between Patrick Henry and hundreds of militia members on one side and the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, and British seamen on the other. The Gunpowder Incident was eventually settled by paying the colonists for the powder.[16]

According to historian Saul Cornell, states passed some of the first gun control laws, beginning with Kentucky’s law to “curb the practice of carrying concealed weapons in 1813.” There was opposition and, as a result, the individual right interpretation of the Second Amendment began and grew in direct response to these early gun control laws, in keeping with this new “pervasive spirit of individualism.” As noted by Cornell, “Ironically, the first gun control movement helped give birth to the first self-conscious gun rights ideology built around a constitutional right of individual self-defense.”[17]:140–141

The individual right interpretation of the Second Amendment first arose in Bliss v. Commonwealth (1822),[18] which evaluated the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state pursuant to Section 28 of the Second Constitution of Kentucky (1799). The right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state was interpreted as an individual right, for the case of a concealed sword cane. This case has been described as about “a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons [that] was violative of the Second Amendment”.[19]

The first state court decision relevant to the “right to bear arms” issue was Bliss v. Commonwealth. The Kentucky court held that “the right of citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State must be preserved entire,…”[20]:161[21]

Also during the Jacksonian Era, the first collective right (or group right) interpretation of the Second Amendment arose. In State v. Buzzard (1842), the Arkansas high court adopted a militia-based, political right, reading of the right to bear arms under state law, and upheld the 21st section of the second article of the Arkansas Constitution that declared, “that the free white men of this State shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their common defense”,[22] while rejecting a challenge to a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons.

The Arkansas high court declared “That the words ‘a well-regulated militia being necessary for the security of a free State’, and the words ‘common defense’ clearly show the true intent and meaning of these Constitutions [i.e., Arkansas and the U.S.] and prove that it is a political and not an individual right, and, of course, that the State, in her legislative capacity, has the right to regulate and control it: This being the case, then the people, neither individually nor collectively, have the right to keep and bear arms.” Joel Prentiss Bishop’s influential Commentaries on the Law of Statutory Crimes (1873) took Buzzard’s militia-based interpretation, a view that Bishop characterized as the “Arkansas doctrine,” as the orthodox view of the right to bear arms in American law.[22][23]

Post Civil War

In the years immediately following the Civil War, the question of the rights of freed slaves to carry arms and to belong to the militia came to the attention of the federal courts. In response to the problems freed slaves faced in the Southern states, the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted.

When the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted, Representative John A. Bingham of Ohio used the Court’s own phrase “privileges and immunities of citizens” to include the first Eight Amendments of the Bill of Rights under its protection and guard these rights against state legislation.[24]

The debate in Congress on the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War also concentrated on what the Southern States were doing to harm the newly freed slaves. One particular concern was the disarming of former slaves.

The Second Amendment attracted serious judicial attention with the Reconstruction era case of United States v. Cruikshank which ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not cause the Bill of Rights, including the Second Amendment, to limit the powers of the State governments, stating that the Second Amendment “has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government.”

Akhil Reed Amar notes in the Yale Law Journal, the basis of Common Law for the first ten amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which would include the Second Amendment, “following John Randolph Tucker’s famous oral argument in the 1887 Chicago anarchist Haymarket Riot case, Spies v. Illinois“:

Though originally the first ten Amendments were adopted as limitations on Federal power, yet in so far as they secure and recognize fundamental rights—common law rights—of the man, they make them privileges and immunities of the man as citizen of the United States…[25]:1270

20th Century

First Half of the 20th Century

Since the late 19th century, with three key cases from the pre-incorporation era, the U.S. Supreme Court consistently ruled that the Second Amendment (and the Bill of Rights) restricted only Congress, and not the States, in the regulation of guns.[26] Scholars predicted that the Court’s incorporation of other rights suggested that they may incorporate the Second, should a suitable case come before them.[27]

National Firearms Act of 1934

The first major federal firearms law passed in the 20th century was the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934. It was passed after Prohibition-era gangsterism peaked with the Saint Valentine’s Day massacre of 1929. The era was famous for criminal use of firearms such as the Thompson submachine gun (Tommy gun) and sawed-off shotgun. Under the NFA, machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, and other weapons fall under the regulation and jurisdiction of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) as described by Title II.[28]

United States v. Miller

In United States v. Miller[29] (1939) the Court did not address incorporation, but whether a sawn-off shotgun “has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia.”[27] In overturning the indictment against Miller, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas stated that the National Firearms Act of 1934, “offend[ed] the inhibition of the Second Amendment to the Constitution.”

The federal government then appealed directly to the Supreme Court. On appeal the federal government did not object to Miller’s release since he had died by then, seeking only to have the trial judge’s ruling on the unconstitutionality of the federal law overturned. Under these circumstances, neither Miller nor his attorney appeared before the Court to argue the case. The Court only heard argument from the federal prosecutor. In its ruling, the Court overturned the trial court and upheld the NFA.[30]

Second Half of the 20th Century

The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA) was passed after the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Senator Robert Kennedy, and African-American activists Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. in the 1960s.[1] The GCA focuses on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by generally prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except among licensed manufacturers, dealers, and importers. It also prohibits selling firearms to certain categories of individuals defined as “prohibited persons.”

In 1986, Congress passed the Firearm Owners Protection Act.[31] It was supported by the National Rifle Association and individual gun rights advocates because it reversed many of the provisions of the GCA and protected gun owners’ rights. It also banned ownership of unregistered fully automatic rifles and civilian purchase or sale of any such firearm made from that date forward.[32][33]

The assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan in 1981 led to enactment of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (Brady Law) in 1993 which established the national background check system to prevent certain restricted individuals from owning, purchasing, or transporting firearms.[34] In an article supporting passage of such a law, retired chief justice Warren E. Burger wrote:

Americans also have a right to defend their homes, and we need not challenge that. Nor does anyone seriously question that the Constitution protects the right of hunters to own and keep sporting guns for hunting game any more than anyone would challenge the right to own and keep fishing rods and other equipment for fishing – or to own automobiles. To ‘keep and bear arms’ for hunting today is essentially a recreational activity and not an imperative of survival, as it was 200 years ago. ‘Saturday night specials’ and machine guns are not recreational weapons and surely are as much in need of regulation as motor vehicles.[35]

A Stockton, California, schoolyard shooting in 1989 led to passage of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994 (AWB or AWB 1994), which defined and banned the manufacture and transfer of “semiautomatic assault weapons” and “large capacity ammunition feeding devices.”[36]

According to journalist Chip Berlet, concerns about gun control laws along with outrage over two high-profile incidents involving the ATF (Ruby Ridge in 1992 and the Waco siege in 1993) mobilized the militia movement of citizens who feared that the federal government would begin to confiscate firearms.[37][38]

Though gun control is not strictly a partisan issue, there is generally more support for gun control legislation in the Democratic Party than in the Republican Party.[39] The Libertarian Party, whose campaign platforms favor limited government regulation, is outspokenly against gun control.[40]

Advocacy Groups

The National Rifle Association (NRA) was founded to promote firearm competency in 1871. The NRA supported the NFA and, ultimately, the GCA.[41] After the GCA, more strident groups, such as the Gun Owners of America (GOA), began to advocate for gun rights.[42] According to the GOA, it was founded in 1975 when “the radical left introduced legislation to ban all handguns in California.”[43] The GOA and other national groups like the Second Amendment Foundation (SAF), Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership (JPFO), and the Second Amendment Sisters (SAS), often take stronger stances than the NRA and criticize its history of support for some firearms legislation, such as GCA. These groups believe any compromise leads to greater restrictions.[44]:368[45]:172

According to the authors of The Changing Politics of Gun Control (1998), in the late 1970s, the NRA changed its activities to incorporate political advocacy.[46] Despite the impact on the volatility of membership, the politicization of the NRA has been consistent and the NRA-Political Victory Fund ranked as “one of the biggest spenders in congressional elections” as of 1998.[46] According to the authors of The Gun Debate (2014), the NRA taking the lead on politics serves the gun industry’s profitability. In particular when gun owners respond to fears of gun confiscation with increased purchases and by helping to isolate the industry from the misuse of its products used in shooting incidents.[47]

The Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence began in 1974 as Handgun Control Inc. (HCI). Soon after, it formed a partnership with another fledgling group called the National Coalition to Ban Handguns (NCBH) – later known as the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence (CSGV). The partnership did not last, as NCBH generally took a tougher stand on gun regulation than HCI.[48]:186 In the wake of the 1980 murder of John Lennon, HCI saw an increase of interest and fundraising and contributed $75,000 to congressional campaigns. Following the Reagan assassination attempt and the resultant injury of James Brady, Sarah Brady joined the board of HCI in 1985. HCI was renamed in 2001 to Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.[49]

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Restriction

In 1996, Congress added language to the relevant appropriations bill which required “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”[50] This language was added to prevent the funding of research by the CDC that gun rights supporters considered politically motivated and intended to bring about further gun control legislation. In particular, the NRA and other gun rights proponents objected to work supported by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, then run by Mark L. Rosenberg, including research authored by Arthur Kellermann.[51][52][53]

Appendix

Notes

- Spitzer, Robert J. (2012). “Policy Definition and Gun Control”. The Politics of Gun Control. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm.

- http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/T-Briefing-Papers/SAS-BP-Civilian-Firearms-Numbers.pdf Estimating Global CivilianHELD Firearms Numbers. Aaron Karp. June 2018

- Desilver, Drew (June 4, 2013). “A Minority of Americans Own Guns, But Just How Many Is Unclear”. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- “Guns: Gallup Historical Trends”, Gallup. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Briefing Paper. Estimating Global Civilian-Held Firearms Numbers. June 2018 by Aaron Karp. Of Small Arms Survey. See box 4 on page 8 for a detailed explanation of “Computation methods for civilian firearms holdings”. See country table in annex PDF: Civilian Firearms Holdings, 2017.

- Strasser, Mr. Ryan (2008-07-01). “Second Amendment”. LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/02/15/its-time-to-bring-back-the-assault-weapons-ban-gun-violence-experts-say/ It’s time to bring back the assault weapons ban, gun violence experts say The Washington Post

- https://slate.com/culture/2018/02/jimmy-kimmel-pleads-for-commonsense-gun-reform-through-tears.html Jimmy Kimmel Cried Again While Addressing the Parkland Shooting, Desperately Pleading for “Common Sense”

- Bruce, John M.; Wilcox, Clyde (1998). “Introduction”. In Bruce, John M.; Wilcox, Clyde (eds.). The Changing Politics of Gun Control. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Spitzer, Robert J. (1995). The Politics of Gun Control. Chatham House.

- Levan, Kristine (2013). “4 Guns and Crime: Crime Facilitation Versus Crime Prevention”. In Mackey, David A.; Levan, Kristine (eds.). Crime Prevention. Jones & Bartlett. p. 438.

They [the NRA] promote the use of firearms for self-defense, hunting, and sporting activities, and also promote firearm safety.

- Larry Pratt. “Firearms: the People’s Liberty Teeth”. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- Terry, Don (1992-03-11). “How Criminals Get Guns: In Short, All Too Easily”. The New York Times.

- Lott, John. More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control Laws (University of Chicago Press, Third edition, 2010)

- Anderson, Jervis (1984). Guns in American Life. Random House.

- Reynolds, Bart (September 6, 2006). “Primary Documents Relating to the Seizure of Powder at Williamsburg, VA, April 21, 1775”. revwar75.com (transcription, amateur?). Horseshoe Bay, Texas: John Robertson. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- Cornell, Saul (2006). A Well-Regulated Militia: The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America. New York City: Oxford University Press.

- Bliss v. Commonwealth, 2 Littell 90 (KY 1822).

- The United States. Anti-Crime Program. Hearings Before Ninetieth Congress, First Session. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967, p. 246.

- Pierce, Darell R. (1982). “Second Amendment Survey” (PDF). Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980s. 10 (1): 155–162. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- Two states, Alaska and Vermont, do not require a permit or license for carrying a concealed weapon to this day, following Kentucky’s original position.

- State v. Buzzard, 4 Ark. (2 Pike) 18 (1842).

- Cornell, Saul (2006). A Well-Regulated Militia – The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America. New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 188.

Dillon endorsed Bishop’s view that Buzzard’s “Arkansas doctrine,” not the libertarian views exhibited in Bliss, captured the dominant strain of American legal thinking on this question.

- Kerrigan, Robert (June 2006). “The Second Amendment and related Fourteenth Amendment” (PDF).

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1992). “The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment”. Yale Law Journal. Faculty Scholarship. 101 (6): 1193–1284.

- See U.S. v. Cruikshank 92 U.S. 542 (1876), Presser v. Illinois 116 U.S. 252 (1886), Miller v. Texas 153 U.S. 535 (1894)

- Levinson, Sanford: The Embarrassing Second Amendment, 99 Yale L.J. 637–659 (1989)

- Boston T. Party (Kenneth W. Royce) (1998). Boston on Guns & Courage. Javelin Press. pp. 3:15.

- “United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939)”. Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- “Telling Miller’s Tale“, Reynolds, Glenn Harlan and Denning, Brannon P.

- S. 49 (99th): Firearms Owners’ Protection Act. GovTrack.us.

- Joshpe, Brett (January 11, 2013). “Ronald Reagan Understood Gun Control”. Hartford Courant (op-ed). Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- Welna, David (January 16, 2013). “The Decades-Old Gun Ban That’s Still On The Books”. NPR. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- Brian Knight (September 2011). “State Gun Policy and Cross-State Externalities: Evidence from Crime Gun Tracing”. Providence RI.

- Burger, Warren E. (January 14, 1990). “The Right To Bear Arms: A distinguished citizen takes a stand on one of the most controversial issues in the nation”. Parade Magazine: 4–6.

- Johnson, Kevin (April 2, 2013). “Stockton school massacre: A tragically familiar pattern”. USA Today. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- Berlet, Chip (September 1, 2004). “Militias in the Frame”. Contemporary Sociologists. 33 (5): 514–521.

All four books being reviewed discuss how mobilization of the militia movement involved fears of gun control legislation coupled with anger over the deadly government mishandling of confrontations with the Weaver family at Ruby Ridge, Idaho and the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas.

- More militia movement sources:

- Chermak, Steven M. (2002). Searching for a Demon: The Media Construction of the Militia Movement. UPNE.

[Chapter 2] describes the primary concerns of militia members and how those concerns contributed to the emergence of the militia movement prior to the Oklahoma City bombing. Two high-profile cases, the Ruby Ridge and Waco incidents, are discussed because they have elicited the anger and concern of the people involved in the movement.

- Crothers, Lane (2003). Rage on the Right: The American Militia Movement from Ruby Ridge to Homeland Security. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97.

Chapter 4 examines the actions surrounding, and the political impact of, the standoff at Ruby Ridge…. Arguably, the siege… lit the match that ignited the militia movement.

- Freilich, Joshua D. (2003). American Militias: State-Level Variations in Militia Activities. LFB Scholarly. p. 18.

[Ruby Ridge and Waco] appear to have taken on a mythological significance within the cosmology of the movement….

- Gallaher, Carolyn (2003). On the Fault Line: Race, Class, and the American Patriot Movement. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 17.

Patriots, however, saw [the Ruby Ridge and Waco] events as the first step in the government’s attempt to disarm the populace and pave the way for imminent takeover by the new world order.

- Chermak, Steven M. (2002). Searching for a Demon: The Media Construction of the Militia Movement. UPNE.

- Spitzer, Robert J.: The Politics of Gun Control, Page 16. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995.

- Harry L. Wilson: “Libertarianism and Support for Gun Control” in Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law, Volume 1, p. 512 (Gregg Lee Carter, Ed., ABC-CLIO, 2012).

- Bennett, Cory (December 21, 2012). “The Evolution of the NRA’s Defense of Guns: A Brief History of the NRA’s Involvement in Legislative Discussions”. National Journal. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- Greenblatt, Alan (December 21, 2012). “The NRA Isn’t The Only Opponent Of Gun Control”. NPR. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- “H.L. “Bill” Richardson – GOA”. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Singh, Robert P. (2003). Governing America: The Politics of a Divided Democracy. Oxford University.

- Tatalovich, Raymond; Daynes, Byron W., eds. (2005). Moral Controversies in American Politics. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- Bruce, John M.; Wilcox, Clyde (1998). The Changing Politics of Gun Control. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 159.

- Cook, Philip J.; Goss, Kristin A. (2014). The Gun Debate: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. p. 201.

- Lambert, Diana (1998). “Trying to Stop the Craziness of This Business: Gun Control Groups”. In Bruce, John M.; Wilcox, Clyde (eds.). The Changing Politics of Gun Control. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Spitzer, Robert J.: The Politics of Gun Control. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995

- Making omnibus consolidated appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1997, and for other purposes PUBLIC LAW 104–208—SEPT. 30, 1996 110 STAT. 3009–244 (PDF)

- Michael Luo (January 25, 2011). “N.R.A. Stymies Firearms Research, Scientists Say”. The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- “22 Times Less Safe? Anti-Gun Lobby’s Favorite Spin Re-Attacks Guns In The Home”. NRA-ILA. December 11, 2001. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Eliot Marshall (January 16, 2013). “Obama Lifts Ban on Funding Gun Violence Research”. ScienceInsider. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Adams, Les (1996). The Second Amendment Primer. A Citizen’s Guidebook To The History, Sources, And Authorities For The Constitutional Guarantee Of The Right To Keep And Bear Arms. Odysseus Editions. Birmingham, Alabama

- Brennan, Pauline G.; Lizotte, Alan J.; McDowall, David (1993). “Guns, Southerness, and Gun Control”. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 9 (3): 289–307.

- Carter, Gregg Lee (2006). Gun Control in the United States: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 408.

- Cramer, Clayton (Winter 1995). “The Racist Roots of Gun Control”. Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy. 42 (2): 17–25. Archived from the original on September 22, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- Davidson, Osha Gray (1998). Under Fire: The NRA and the Battle for Gun Control. University of Iowa Press. p. 338.

- Edel, Wilbur (1995). Gun Control: Threat to Liberty or Defense against Anarchy?. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers.

- Goss, Kristin A. (2008). Disarmed: The Missing Movement for Gun Control in America. Princeton University Press. p. 304.

- Halbrook, Stephen P. (2013). Gun Control in the Third Reich: Disarming the Jews and “Enemies of the State”. Independent Institute.

- Kates, Don B.; Mauser, Gary (Spring 2007). “Would Banning Firearms reduce Murder and Suicide? A Review of International and Some Domestic Evidence” (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy. 30 (2): 649–694. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-28.

- Langbein, Laura I.; Lotwis, Mark A. (August 1990). “Political Efficacy of Lobbying and Money: Gun Control in the U.S. House, 1986”. Legislative Studies Quarterly. 15 (3): 413–440

- McGarrity, Joseph P.; Sutter, Daniel (2000). “A Test of the Structure of PAC Contracts: An Analysis of House Gun Control Votes in the 1980s”. Southern Economic Journal. 67 (1): 41–63.

- Melzer, Scott (2009). Gun Crusaders: The NRA’s Culture War. New York University Press. p. 336.

- Snow, Robert L. (2002). Terrorists Among Us: The Militia Threat. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus.

- Tahmassebi, Stefan B. (1991). “Gun Control and Racism”. George Mason University Civil Rights Law Journal. 2 (1): 67–100.

- Utter, Glenn H. (2000). Encyclopedia of Gun Control and Gun Rights. Phoenix, Ariz.: Oryx. p. 378.

- Winkler, Adam (2011). Gunfight: The Battle over the Right to Bear Arms in America. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 361.

- Wogan, J. B. (May 6, 2014). “Lessons in Gun Control from Australia and Brazil”. Emergency Management.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 02.01.2004, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.