By Dr. Joshua J. Mark

Professor of Philosophy

Marist College

Introduction

Is it possible to have a heart that is lighter than a feather? To the ancient Egyptians it was not only possible but highly desirable. The after-life of the ancient Egyptians was known as the Field of Reeds and was a land very much like one’s life on earth save that there was no sickness, no disappointment and, of course, no death. One lived eternally by the streams and beneath the trees which one had loved so well in one’s life on earth.

An Egyptian tomb inscription from 1400 BCE, regarding one’s afterlife, reads,

May I walk every day unceasing on the banks of my water, may my soul rest on the branches of the trees which I have planted, may I refresh myself in the shadow of my sycamore (Nardo, 10).

To reach the eternal paradise of the Field of Reeds, however, one had to pass through the trial by Osiris, Lord of the Underworld and just Judge of the Dead, in the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Two Truths), and this trial involved the weighing of one’s heart against the feather of truth.

The Soul in Ancient Egypt

A person’s soul was thought to be immortal, an eternal being whose stay on earth was only one part of a much larger and grander journey. This soul was said to consist of nine separate parts:

- Khat was the physical body

- Ka was one’s double-form

- Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and heaven

- Shuyet was the shadow self

- Akh the immortal, transformed self

- Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh

- Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil

- Ren was one’s secret name.

All nine of these aspects were part of one’s earthly existence and, at death, the Akh (with the Sahu and Sechem) appeared before Osiris in the Hall of Truth and in the presence of the Forty-Two Judges to have one’s heart (Ab) weighed in the balance on a golden scale against the white feather of truth.

The ancient Egyptians recognized that when the soul first awoke in the afterlife it would be disoriented and might not remember its life on earth, its death, or what it was to do next. In order to help the soul continue on its journey, artists and scribes would create paintings and text related to one’s life on the walls of one’s tomb (now known as the Pyramid Texts) which then developed into the Coffin Texts and the famous Egyptian Book of the Dead.

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest religious works from ancient Egypt dated to c. 2400-2300 BCE. The Coffin Texts developed later from the Pyramid Texts in c. 2134-2040 BCE while the Egyptian Book of the Dead (actually known as the Book on Coming Forth by Day) was created c. 1550-1070 BCE. All three of these works served the same purpose: to remind the soul of its life on earth, comfort its distress and disorientation, and direct it on how to proceed through the afterlife.

The Hall of Truth

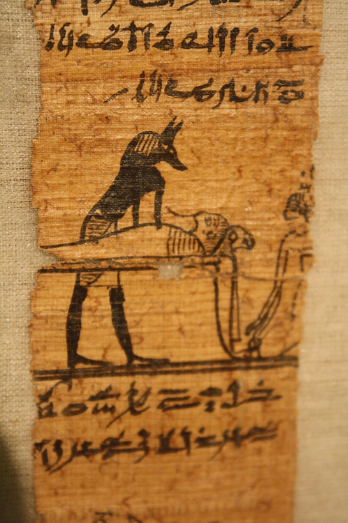

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead it is recorded that, after death, the soul would be met by the god Anubis who would lead it from its final resting place to the Hall of Truth. Images depict a queue of souls standing in the hall and one would join this line to await judgment. While waiting, one would be attended to by goddesses such as Qebhet, daughter of Anubis, the personification of cool, refreshing water. Qebhet would be joined by others such as Nephthys and Serket in comforting the souls and providing for them.

When it came one’s turn, Anubis would lead the soul to stand before Osiris and the scribe of the gods, Thoth in front of the golden scales. The goddess Ma’at, personification of the cultural value of ma’at(harmony and balance) would also be present and these would be surrounded by the Forty-Two Judges who would consult with these gods on one’s eternal fate.

The soul would then recite the Negative Confessions in which one needed to be able to claim, honestly, that one had not committed certain sins. These confessions sometimes began with the prayer, “I have not learnt the things which are not” meaning that the soul strove in life to devote itself to matters of lasting importance rather than the trivial matters of everyday life. There was no single set list of Negative Confessions, however, just as there was no set list of “sins” which would apply to everyone. A military commander would have a different list of sins than, say, a judge or a baker.

The negative declarations, always beginning with “I have not…” or “I did not…”, following the opening prayer went to assure Osiris of the soul’s purity and ended, in fact, with the statement, “I am pure” repeated a number of times. Each sin listed was thought to have disrupted one’s harmony and balance while one lived and separated the person from their purpose on earth as ordained by the gods. In claiming purity of the soul, one was asserting that one’s heart was not weighed down with sin. It was not the soul’s claim to purity which would win over Osiris, however, but, instead, the weight of the soul’s heart.

The Judgement of Osiris

The `heart’ of the soul was handed over to Osiris who placed it on a great golden scale balanced against the white feather of Ma’at, the feather of truth on the other side. If the soul’s heart was lighter than the feather then the gods conferred with the Forty-Two Judges and, if they agreed that the soul was justified, the person could pass on toward the bliss of the Field of Reeds.

According to some ancient texts, the soul would then embark on a dangerous journey through the afterlife to reach paradise and they would need a copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead to guide them and assist them with spells to recite if they ran into trouble. According to others, however, after justification it was only a short journey from the Hall of Truth to paradise.

The soul would leave the hall of judgment, be rowed across Lily Lake, and enter the eternal paradise of the Field of Reeds in which one received back everything taken by death. For the soul with the heart lighter than a feather, those who had died earlier were waiting along with one’s home, one’s favorite objects and books, even one’s long lost pets.

Should the heart prove heavier, however, it was thrown to the floor of the Hall of Truth where it was devoured by Amenti (also known as Amut), a god with the face of a crocodile, the front of a leopard and the back of a rhinoceros, known as “the gobbler”. Once Amenti devoured the person’s heart, the individual soul then ceased to exist. There was no `hell’ for the ancient Egyptians; their `fate worse than death’ was non-existence.

The Field Of Reeds and Egyptian Love of Life

It is a popular misconception that the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with death when, in reality, they were in love with life and so, naturally, wished it to continue on after bodily death. The Egyptians enjoyed singing, dancing, boating, hunting, fishing and family gatherings just as people enjoy them today.

The most popular drink in ancient Egypt was beer which, although considered a food consumed for nutritional purposes, was also enjoyed at the many celebrations Egyptians observed throughout the year. Drunkenness was not considered a sin as long as one consumed alcohol at an appropriate time for an appropriate reason. Sex, whether in marriage or out, was also viewed liberally as a natural and enjoyable activity.

The elaborate funerary rites, mummification, and the placement of Shabti dolls were not meant as tributes to the finality of life but to its continuance and the hope that the soul would win admittance to the Field of Reeds when the time came to stand before the scales of Osiris. The funerary rites and mummification preserved the body so the soul would have a vessel to emerge from after death and return to in the future if it chose to visit earth.

One’s tomb, and statuary depicting the deceased, served as an eternal home for the same reason – so the soul could return to earth to visit – and shabti dolls were placed in a tomb to do one’s work in the afterlife so that one could relax whenever one wished. When the funeral was over, and all the prayers had been said for the safe travel of the departed, survivors could return to their homes consoled by the thought that their loved one was justified and would find joy in paradise. Even so, not all the prayers nor all the hopes nor the most elaborate rites could help that soul whose heart was heavier than the white feather of truth.

Bibliography

- Bunson, M. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Gramercy Books, 1991.

- David, R. Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books, 2003.

- Faulkner, R. O. The Egyptian Book of the Dead. Chronicle Books, 1991.

- Ikram, S. Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, 2015.

- Nardo, D. Living in Ancient Egypt. Thompson/Gale, 2004.

- Pinch, G. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Shaw, I. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Van De Mieroop, M. A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Wallis Budge, E. A. The Egyptian Book of the Dead. Dover Publications, 1967.

- Wilkinson,R. H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2010.

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 03.30.2018, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.