The ancient world demonstrates with particular clarity that political authority was never exercised in abstraction from material systems.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Technology as a Political Force, not a Neutral Tool

Technology in the ancient world was not an external force acting upon politics, nor was it merely a set of tools applied at the discretion of rulers. It functioned instead as a structuring element that shaped what forms of political authority were possible, sustainable, and intelligible within particular historical contexts. Decisions about governance, warfare, administration, and territorial control were constrained and enabled by material systems that determined how resources could be extracted, how information could be stored and transmitted, and how force could be organized and deployed. To understand ancient political life without attending to these systems is to mistake outcomes for causes.

What follows adopts a deliberately narrow definition of technology, focusing not on isolated inventions but on integrated material systems: metallurgy, writing and accounting practices, transport and communication networks, agricultural regimes, and infrastructural projects. These systems mattered politically because they structured access. Control over metals shaped who could bear arms. Control over records shaped who could tax, legislate, and remember. Control over movement and communication shaped the scale at which power could operate. In each case, technology did not dictate political outcomes, but it set durable parameters within which political choice occurred. The emphasis here is not determinism but constraint and possibility, a distinction long recognized in scholarship on ancient economies and states.1

Ancient political actors were not unaware of these dynamics. Rulers and governing elites routinely invested in, restricted, centralized, or guarded technical knowledge and material systems because they understood their political implications. Administrative archives, standardized weights and measures, military infrastructure, and road networks were not incidental byproducts of state formation. They were deliberate responses to the problems created by scale, population density, and territorial ambition. At the same time, technological change could destabilize existing orders by redistributing access to violence, information, or subsistence in ways that institutions were unable to absorb. Political collapse and political innovation often followed the same material shifts.

By treating technology as a structuring element of political life, I seek to move beyond narratives of progress or ingenuity and toward an analysis of power grounded in material reality. The ancient world offers particularly clear evidence of this relationship because political authority there was more visibly bounded by physical constraints than in later industrial societies. The argument advanced in the sections that follow is not that technology caused political change in isolation, but that political systems repeatedly rose, adapted, or failed in response to the opportunities and pressures generated by the material systems upon which they depended.2

Bronze Age Political Economies and the Monopoly of Force

Bronze Age political systems were structured around the material requirements of bronze production itself. Unlike later iron-based economies, bronze metallurgy depended on the coordinated acquisition of copper and tin, resources that were rarely co-located and often sourced from distant regions. This dependence on long-distance exchange encouraged the development of centralized administrative centers capable of managing trade, storage, and redistribution. In the eastern Mediterranean and Near East, palatial institutions functioned as logistical hubs through which metals, labor, and finished goods flowed, binding political authority to control over material networks rather than territorial breadth alone.3

This material concentration had direct consequences for the organization of violence. Weapons manufacture required skilled specialists, controlled workshops, and steady access to imported metals, all of which were overseen by palace administrations. As a result, the capacity for organized warfare remained largely confined to elites embedded within state structures. Chariot warfare illustrates this dynamic particularly clearly, as chariots required not only bronze fittings and weapons but also trained personnel, horses, and ongoing logistical support that only centralized economies could sustain.4 Military power therefore reinforced social hierarchy, with coercive force serving as an extension of administrative control rather than an independent source of authority.

The stability of these political economies depended on the continued functioning of their trade and administrative systems. Diplomatic archives from the Late Bronze Age reveal a tightly interconnected world of states exchanging metals, prestige goods, and military assistance within an international order that was both cooperative and fragile. Disruptions to supply routes or administrative capacity could rapidly undermine political authority, as centralized systems had limited flexibility in the face of material shortages or external shocks.5 The same structures that enabled elite dominance also constrained adaptation.

When these systems came under sustained pressure in the late second millennium BCE, their rigidity became a liability. The concentration of force within palace institutions left few mechanisms for political resilience once access to metals, labor, or military technology was disrupted. As centralized control weakened, the monopoly of violence that had defined Bronze Age authority eroded alongside it. The decline of these political economies did not simply mark the end of a technological era but exposed the extent to which political legitimacy had been anchored in fragile material arrangements rather than broadly distributed capacity.6

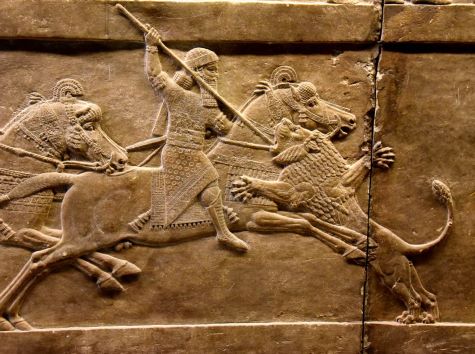

Iron Metallurgy and the Breakdown of Elite Military Control

The spread of iron metallurgy in the early first millennium BCE altered the political organization of violence by changing who could realistically acquire weapons. Iron ores were more geographically widespread than the copper and tin required for bronze, reducing dependence on long-distance exchange networks that had previously been overseen by palace institutions.7 This shift weakened elite control over arms production not because iron was technologically superior at first, but because its material availability undermined the administrative bottlenecks upon which Bronze Age military monopolies depended.

The political effects of iron emerged unevenly and over time. Bronze continued to be used alongside iron for generations, and early iron objects were often of inconsistent quality.8 The significance of iron lay instead in its cumulative impact on access. As ironworking knowledge diffused beyond centralized workshops, communities that had relied on palatial protection gained greater capacity for independent defense. This redistribution of coercive capability gradually altered the social composition of armies, favoring larger bodies of infantry whose effectiveness depended on numbers and coordination rather than aristocratic specialization.

In the eastern Mediterranean, these developments coincided with the declining strategic centrality of chariot warfare. Chariots required sustained elite investment in equipment, horses, training, and logistical support, conditions that became harder to maintain as centralized political economies weakened.9 As infantry forces became more viable, military participation broadened, and political authority increasingly had to engage populations capable of bearing arms themselves. In the Greek world, this process unfolded slowly and unevenly, but it contributed to the eventual emergence of citizen militias whose political leverage derived from collective military obligation rather than inherited status.

Iron metallurgy did not abolish hierarchy, nor did it automatically produce inclusive political systems. Elites adapted by redefining command structures, consolidating leadership roles, or integrating new military constituencies into evolving institutions. Where adaptation succeeded, political systems stabilized in altered forms. Where it failed, fragmentation followed. The historical significance of iron therefore lies in its political effects rather than its technical properties: by widening access to the means of violence, it destabilized inherited structures of elite military control and forced ancient political systems to renegotiate the relationship between authority and force.10

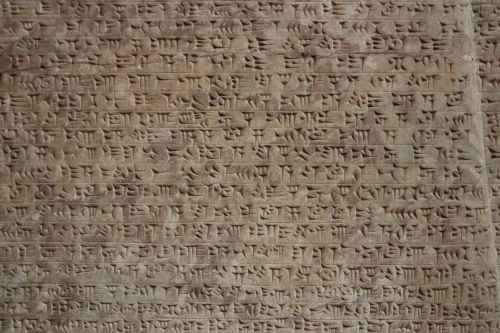

Writing Systems and the Emergence of Administrative States

Writing systems in the ancient world emerged first as instruments of administration rather than as vehicles of literature or expression. The earliest attestations of writing in Mesopotamia are inseparable from accounting practices related to temple and palace economies, recording quantities of grain, livestock, and labor obligations rather than narrative or symbolic communication.11 From their inception, written records functioned as tools for managing resources at scale, enabling authorities to track obligations across time and space in ways that oral systems could not sustain.

The political significance of writing lay not in literacy itself, which remained highly restricted, but in the creation of durable administrative memory. Written records allowed states to enforce continuity across reigns, standardize procedures, and project authority beyond the physical presence of rulers. In Egypt, for example, taxation, corvée labor, and land management depended on scribal institutions that translated agricultural output into legible obligations owed to the state.12 Control over writing thus became a form of political power, as access to records determined who could audit, challenge, or enforce administrative decisions.

Writing also transformed the relationship between law and authority. The codification of legal norms did not eliminate discretionary judgment, but it reshaped how legitimacy was articulated and defended. Written law created the appearance of consistency and permanence, allowing rulers to frame governance as adherence to established order rather than personal will. In Mesopotamian contexts, legal texts functioned as reference points within bureaucratic practice rather than as universally applied statutes, reinforcing the authority of institutions that controlled their interpretation and application.13

As administrative states expanded, writing enabled increasingly complex forms of coordination. Tribute systems, military provisioning, and diplomatic exchange all depended on standardized documentation that could be transmitted across regions. Correspondence between Near Eastern rulers demonstrates how writing facilitated interstate relations by stabilizing expectations and obligations among political elites.14 The ability to document promises, deliveries, and status claims reduced reliance on immediate coercion and allowed political systems to operate across greater distances.

At the same time, the concentration of writing within bureaucratic institutions created new vulnerabilities. Administrative systems depended on trained specialists whose expertise could not be easily replaced. Disruptions to scribal training, archival maintenance, or record transmission could undermine state capacity even when material resources remained available. The collapse or fragmentation of bureaucratic continuity often preceded or accompanied broader political breakdown, revealing the extent to which authority had become dependent on informational control rather than sheer force.15

Writing systems therefore did not simply reflect the emergence of administrative states; they actively shaped their structure and limits. By converting economic activity, legal norms, and political relationships into durable records, writing redefined what governance could accomplish and how power could be exercised. Yet this same dependence on written administration constrained flexibility, binding political authority to institutions whose effectiveness relied on stability, specialization, and sustained investment. The administrative state was, in this sense, both empowered and constrained by the technologies that made it possible.16

Standardized Value: Coinage, Authority, and Political Trust

The introduction of coinage in the ancient Mediterranean represented a political transformation before it was an economic one. Early coinage did not emerge spontaneously from market exchange but from state and civic authorities seeking reliable mechanisms to standardize value, facilitate payment, and assert control over economic interactions. The earliest coins, produced in western Anatolia in the late seventh century BCE, were issued under authoritative oversight and marked with symbols that signaled legitimacy rather than intrinsic worth.17 From the outset, coinage functioned as a technology of governance that linked material value to political authority.

Coinage altered the relationship between rulers and subjects by embedding trust within an officially sanctioned medium. Unlike weighed bullion or barter, coined money depended on collective confidence that a stamped object would be accepted at face value within a given political community. This confidence rested not on metallurgy alone but on the issuing authority’s capacity to enforce acceptance, regulate supply, and punish fraud.18 In this sense, coinage externalized trust, relocating it from interpersonal exchange to institutional guarantee. Political power thus became materially present in everyday transactions, reinforcing the visibility and reach of governing bodies.

The military implications of standardized coinage were especially significant. Coined money facilitated regularized payment of soldiers, reducing reliance on plunder, ad hoc compensation, or elite patronage. In Greek poleis, the ability to pay hoplites and sailors in standardized currency supported the expansion of citizen-based military forces whose service was tied to civic obligation rather than aristocratic dependence.19 Coinage did not create mass armies on its own, but it enabled political systems to sustain them more predictably, reshaping the balance between state authority and individual participation in warfare.

Coinage also transformed political scale by enabling states to integrate diverse economic activities within a common framework of value. Markets, taxation, tribute, and fines could now be coordinated through a single medium, simplifying administration and enhancing fiscal reach. In larger imperial contexts, monetary systems allowed authorities to extract resources from distant regions without constant physical presence, converting local production into transportable value.20 This abstraction of economic obligation expanded the practical limits of governance, though it also increased dependence on administrative coherence and monetary stability.

At the same time, the political power of coinage was not absolute. Monetary trust could erode through debasement, overproduction, or loss of confidence in issuing authorities. Ancient states were well aware of these risks and often guarded minting rights closely as a core attribute of sovereignty. The political significance of coinage therefore lay not simply in its circulation, but in the ongoing institutional effort required to sustain its credibility. By binding value to authority, coinage made economic life more governable while simultaneously exposing political systems to new forms of instability when that authority weakened.21

Horse Technologies and the Expansion of Territorial Power

Horse-related technologies transformed ancient political power by expanding the scale at which authority could be projected and maintained. Domestication alone did not create empires, but innovations such as effective bridles, bits, and riding techniques allowed mounted movement to become a reliable instrument of command rather than a marginal advantage. By the early first millennium BCE, states and confederations that mastered mounted mobility were able to traverse distances that previously constrained political control, reshaping the relationship between geography and governance.22 The political significance of these developments lay in speed, reach, and coordination rather than battlefield dominance alone.

Mounted mobility altered the organization of warfare by enabling rapid reconnaissance, communication, and force deployment across wide territories. Cavalry units were initially supplements rather than replacements for infantry, but their strategic value lay in flexibility rather than mass. States that incorporated horse technologies could respond more quickly to threats, suppress revolts, and maintain pressure on peripheral regions. This capability proved especially consequential in frontier zones, where the ability to move forces swiftly often mattered more than numerical superiority. The political advantage of cavalry thus rested on operational range rather than tactical supremacy.23

Horse technologies also reshaped imperial administration by compressing distance between center and periphery. Courier systems, inspection tours, and military patrols depended on mounted travel to sustain regular contact across large domains. In the Achaemenid Empire, mounted relays enabled the transmission of orders and intelligence at speeds unmatched by earlier states, allowing rulers to govern territories that would otherwise have exceeded practical administrative limits.24 The horse functioned here as an infrastructural technology, binding space into governable units through mobility rather than construction.

These transformations did not eliminate political constraints. Maintaining horses required pasture, fodder, skilled handlers, and continuous logistical investment, limiting their effectiveness in densely populated or environmentally marginal regions. Elites who controlled horse resources often acquired disproportionate influence, reinforcing new hierarchies even as old ones weakened. Horse technologies therefore did not democratize power but redistributed it, favoring political systems capable of sustaining mobile control over territory. Their historical importance lies in how they enabled states to think and act at scales previously beyond reach, redefining the spatial limits of ancient governance.25

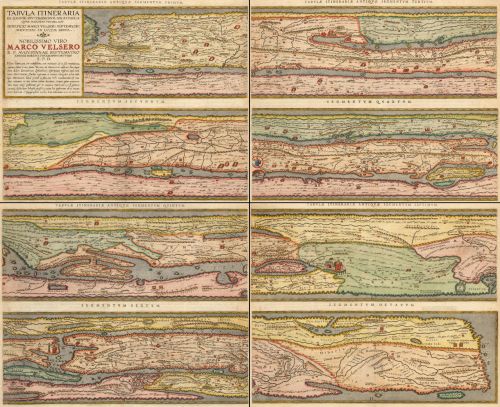

Infrastructure and the Political Control of Space

Large-scale infrastructure projects in the ancient world were among the clearest expressions of political authority translated into material form. Roads, canals, bridges, and water systems did not simply facilitate economic activity; they reshaped territory into administrable space. The capacity to design, build, and maintain infrastructure required centralized coordination of labor, resources, and technical expertise, tying political legitimacy to visible material order. In this sense, infrastructure functioned as a technology of governance that rendered landscapes legible and usable for state purposes.26

Road systems illustrate this dynamic particularly clearly. In the Roman world, roads were not designed primarily to promote commerce but to enable rapid military movement, administrative travel, and reliable communication across vast territories. Their standardized construction and durability reduced the friction of distance, allowing the state to project authority well beyond urban centers.27 Control over road networks also enabled taxation, policing, and judicial oversight by structuring how people and goods moved through space, binding peripheral regions more tightly to imperial centers.

Water infrastructure played an equally significant political role. Aqueducts, canals, and irrigation systems required sustained investment and long-term maintenance, making them markers of stable authority rather than short-term ambition. In Rome, aqueducts not only supplied cities with water but also symbolized the state’s capacity to harness nature for public use, reinforcing civic identity and dependence on centralized provision.28 In agrarian contexts, irrigation systems converted variable environments into predictable sources of surplus, allowing states to extract resources more reliably while increasing administrative oversight of rural populations.

Infrastructure also imposed constraints on political power. Large projects created fixed obligations that could not easily be abandoned without undermining legitimacy. Roads required maintenance, aqueducts demanded continuous oversight, and canals needed constant labor to prevent failure. When states lost the capacity to sustain these systems, infrastructural decay often preceded or accompanied political fragmentation. Archaeological evidence from late antiquity shows that the breakdown of maintenance regimes could rapidly reverse centuries of spatial integration, shrinking the effective reach of authority even where formal political structures persisted.29

The political significance of infrastructure therefore lay not only in its construction but in its endurance. By transforming space into a durable framework for governance, infrastructure allowed ancient states to operate at scales that would otherwise have been impossible. At the same time, it bound political authority to ongoing material commitments that exposed weakness when administrative capacity faltered. Infrastructure was thus both an instrument of control and a measure of political resilience, revealing the intimate relationship between material systems and the geography of power.30

Communication Networks and the Governance of Distance

Political authority in the ancient world was limited not only by geography but by the speed at which information could travel. Communication networks transformed these limits by allowing rulers to issue commands, receive reports, and coordinate action across distances that would otherwise have fractured governance. Such systems did not eliminate delay, but they regularized it, turning uncertainty into predictable intervals. The ability to govern at scale therefore depended less on territorial size than on the reliability of information flow between center and periphery.31

One of the earliest and most effective examples of institutionalized long-distance communication appears in the Achaemenid Empire. Administrative relay systems using mounted couriers enabled messages to traverse imperial territory with unprecedented speed, binding distant provinces to central authority. These networks were not improvised conveniences but state-managed systems integrated into imperial administration and security. Their effectiveness lay in consistency rather than novelty, allowing rulers to maintain oversight across regions that would otherwise have exceeded practical control.32

Communication networks also reshaped military command. The coordination of troop movements, provisioning, and frontier defense depended on the timely transmission of intelligence. Without reliable messaging, armies became autonomous forces, vulnerable to isolation or insubordination. In both Persian and later Roman contexts, communication systems allowed political authorities to retain strategic control even when direct presence was impossible. This capacity reduced reliance on local discretion while increasing the reach of centralized command structures.33

In the Roman Empire, the cursus publicus served as a state-controlled communication and transport system that linked administrative centers through designated routes and stations. Access to this network was restricted, reinforcing its function as an instrument of governance rather than general mobility. The system supported administrative correspondence, military logistics, and judicial oversight, enabling imperial authority to function through documentation and directive rather than constant coercion.34 The effectiveness of Roman governance rested as much on this informational infrastructure as on legions or taxation.

At the same time, communication networks introduced new dependencies. Administrative authority became contingent on the maintenance of routes, stations, personnel, and animals. Disruption to these systems could paralyze governance even when military strength remained intact. Periods of political instability often coincided with the degradation of communication capacity, as delays compounded uncertainty and weakened central coordination. The governance of distance thus depended on sustained institutional investment rather than technological superiority alone.35

Communication technologies did not abolish the challenges of ruling large territories, but they transformed their nature. Distance became a managerial problem rather than an absolute barrier, redefining what political systems could plausibly attempt. By stabilizing expectations of response time and information reliability, ancient communication networks enabled new forms of centralized authority while simultaneously exposing states to failure when those networks faltered. The limits of ancient governance were therefore set not only by armies or resources, but by the fragile systems that carried words, orders, and intelligence across space.36

Agricultural Systems, Surplus, and Institutional Complexity

Agricultural systems formed the material foundation upon which ancient political complexity rested, not because they generated abundance alone, but because they created persistent problems of coordination, extraction, and control. The adoption of irrigation, plow agriculture, and crop management techniques increased productivity while simultaneously binding communities to fixed landscapes. This combination of surplus and immobility transformed subsistence into a political matter, as authorities sought to regulate land use, labor obligations, and seasonal rhythms in order to stabilize food supply and extract predictable returns.37

Surplus production did not automatically strengthen political authority. On the contrary, it intensified the need for institutions capable of managing risk, redistribution, and conflict. Irrigated agriculture in Mesopotamia illustrates this tension clearly, as canal systems required collective labor and ongoing maintenance that could not be sustained without centralized coordination. Administrative oversight emerged not simply to collect surplus, but to prevent infrastructural failure that would have undermined production altogether.38 In this context, governance developed as a response to ecological and logistical constraints rather than as an abstract assertion of power.

In Egypt, agricultural administration was shaped by different environmental conditions but similar institutional pressures. The predictability of the Nile flood allowed for relatively stable agricultural cycles, yet translating that stability into state revenue depended on systematic land measurement, yield assessment, and labor organization. Scribal records and cadastral surveys converted agricultural output into legible obligations owed to central authority, binding rural producers to administrative frameworks that extended well beyond local communities.39 Political power thus rested not merely on control of land, but on control of information about land.

As agricultural systems intensified, they also increased population density, compounding administrative challenges. Larger populations demanded more complex systems of storage, distribution, and dispute resolution, while surplus itself became a source of inequality and social tension. Authorities faced the problem of ensuring subsistence for non-producing populations, including soldiers, administrators, and artisans, without provoking resistance from agricultural producers. Institutional complexity expanded as a means of managing these pressures rather than eliminating them.40

Agricultural technologies also shaped the spatial organization of political authority. Irrigation networks, terracing, and field systems structured settlement patterns and constrained mobility, making populations more legible and taxable while reducing options for withdrawal or resistance. These material arrangements facilitated governance by fixing communities in place, but they also increased vulnerability to administrative failure. Crop shortfalls, canal breakdowns, or mismanagement could rapidly escalate into political crises, revealing the dependence of authority on ecological stability.41

Agricultural surplus therefore functioned as a double-edged foundation for ancient states. It enabled specialization, urbanization, and institutional differentiation, but it also locked political systems into ongoing obligations of management and redistribution. Rather than viewing agriculture as a simple precursor to state formation, it is more accurate to understand it as a continuous source of political strain. Authority expanded in response to surplus, yet remained perpetually constrained by the material and social systems that made that surplus possible.42

Political Choice and Technological Mediation

Technological systems in the ancient world did not operate independently of political intention. While material conditions shaped what forms of authority were possible, political actors actively mediated how technologies were adopted, restricted, or concentrated. Decisions about who could access weapons, who could read or write administrative records, and who could move freely across territory were rarely neutral. Elites understood that control over technological systems could stabilize authority just as effectively as military force, and they acted accordingly. The political significance of technology therefore lay not only in its material properties but in the institutional choices that governed its use.43

One of the clearest examples of technological mediation appears in the management of literacy and recordkeeping. Writing systems enabled administration, but access to literacy was often deliberately constrained. Scribal training required time, resources, and institutional sponsorship, ensuring that bureaucratic knowledge remained concentrated within narrow social strata. This restriction was not incidental; it preserved administrative continuity while limiting challenges to authority rooted in informational control. Political systems thus transformed writing from a broadly applicable technology into a guarded institutional resource.44

Military technologies were similarly mediated through political choice. Even as iron metallurgy expanded access to weapons, states developed mechanisms to regulate military participation through training requirements, command hierarchies, and logistical dependence. Control over fortifications, arsenals, and supply systems allowed authorities to reassert influence over armed populations that might otherwise have destabilized existing orders. The distribution of force was therefore never purely technological; it was shaped by deliberate institutional frameworks designed to manage the risks introduced by wider access to arms.45

Technological mediation also operated through selective investment and neglect. States chose which infrastructures to maintain, which communication routes to prioritize, and which agricultural systems to support. These decisions reflected political priorities rather than technical necessity alone. When investment aligned with institutional capacity, technology reinforced authority. When it outpaced administrative competence or ecological limits, it exposed vulnerability. The history of ancient political systems thus reveals not a deterministic march driven by innovation, but a continuous negotiation between material possibilities and political judgment.46

Conclusion: Technology, Power, and the Limits of Ancient Governance

The ancient world demonstrates with particular clarity that political authority was never exercised in abstraction from material systems. Metallurgy, writing, agriculture, mobility, infrastructure, and communication did not merely support governance; they defined its practical limits and possibilities. States emerged, expanded, and fractured within the constraints imposed by these technologies, adapting institutional forms to match what could be extracted, coordinated, and enforced. Political power, in this context, was inseparable from the capacity to manage material complexity over time.

At the same time, technological capacity did not dictate political outcomes. Similar material systems produced markedly different political forms depending on how they were organized, restricted, or distributed. Bronze did not require palatial autocracy, nor did iron guarantee participatory governance. Writing could centralize authority or expose its fragility. Coinage could stabilize political trust or undermine it. These variations underscore a central conclusion of this essay: technology structured political choice, but it did not replace it. Ancient political actors operated within material constraints, yet they exercised agency in determining how those constraints would be navigated.47

The recurring pattern across ancient societies is not technological progress but institutional tension. Each expansion of material capacity introduced new demands for coordination, surveillance, and legitimacy. Infrastructure required maintenance. Communication required continuity. Surplus required redistribution. As political systems grew more complex, they also grew more dependent on the very technologies that enabled their expansion. When administrative capacity faltered, the material foundations of authority often collapsed first, revealing the extent to which governance rested on fragile systems of organization rather than enduring coercive dominance.48

The political history of the ancient world thus offers a cautionary framework rather than a developmental narrative. Technology enabled power, but it also exposed its limits. Authority expanded through material systems that simultaneously constrained flexibility and amplified risk. By examining these dynamics historically, it becomes clear that the relationship between technology and power has never been neutral or inevitable. It has always been contingent, negotiated, and bounded by the capacity of institutions to sustain the material systems upon which governance depends.49

Appendix

Footnotes

- Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1934), 3–15.

- Moses I. Finley, The Ancient Economy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 21–34.

- Mario Liverani, The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy (London: Routledge, 2013), 161–170.

- Robert Drews, The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 104–122.

- Trevor Bryce, Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East (London: Routledge, 2003), 1–18.

- Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 256–271.

- Jane C. Waldbaum, “From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology LIV (1978): 106-120.

- A. Bernard Knapp, The Archaeology of Cyprus: From Earliest Prehistory through the Bronze Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 451–453.

- Drews, The End of the Bronze Age, 204–210.

- Ian Morris, War! What Is It Good For? Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014), 118–126.

- Denise Schmandt-Besserat, How Writing Came About (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), 73–92.

- Juan Carlos Moreno García, “The Territorial Administration of the Kingdom in Ancient Egypt,” in Ancient Egyptian Administration, ed. Juan Carlos Moreno García (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 85–110.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005), 97–115.

- Bryce, Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East, 19–42.

- Michael Hudson and Cornelia Wunsch, eds., Creating Economic Order: Record-Keeping, Standardization, and the Development of Accounting in the Ancient Near East (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2004), 1–22.

- Liverani, The Ancient Near East, 285–301.

- Andrew Meadows, “Money, Freedom, and Empire in the Hellenistic World,” in Money and Its Uses in the Ancient Greek World, ed. Andrew Meadows and Kirsty Shipton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 53–60.

- David Schaps, The Invention of Coinage and the Monetization of Ancient Greece (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004), 89–103.

- Peter Krentz, The Battle of Marathon (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 62–67.

- Richard Duncan-Jones, Money and Government in the Roman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 3–20.

- Christopher Howgego, Ancient History from Coins (London: Routledge, 1995), 21–38.

- David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel, and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 201–214.

- Philip Sidnell, Warhorse: Cavalry in Ancient Warfare (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006), 41–58.

- Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996), 357–366.

- Michael Whitby, “The Army and Defense,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 14 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 401–405.

- Michael Mann, The Sources of Social Power, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 130–137.

- Raymond Chevallier, Roman Roads (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 11–26.

- Frontinus, De aquaeductu urbis Romae, trans. R. H. Rodgers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 1.1–1.5.

- Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 87–98.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 101–109.

- Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, 87–94.

- Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 365–368.

- Herodotus, Histories, 8.98.

- A. Kolb, Transport and Communication in the Roman State (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2000), 45–62.

- Fergus Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 252–268.

- Mann, The Sources of Social Power, vol. 1, 153–158.

- V. Gordon Childe, Man Makes Himself (London: Watts & Co., 1936), 62–74.

- Robert McC. Adams, Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 45–60.

- Juan Carlos Moreno García, “The Management of Agricultural Estates in Pharaonic Egypt,” in Ancient Egyptian Administration, ed. Juan Carlos Moreno García (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 457–478.

- Ian Morris, Why the West Rules—for Now (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), 84–91.

- James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 24–33.

- Bruce Trigger, Understanding Early Civilizations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 50–58.

- Finley, The Ancient Economy, 34–42.

- Hudson and Wunsch, eds., Creating Economic Order, 9–17.

- Victor Davis Hanson, The Western Way of War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), 26–31.

- Trigger, Understanding Early Civilizations, 92–104.

- Trigger, Understanding Early Civilizations, 545–552.

- Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, 138–146.

- Mann, The Sources of Social Power, vol. 1, 178–185.

Bibliography

- Adams, Robert McC. Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Anthony, David W. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996.

- Bryce, Trevor. Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Chevallier, Raymond. Roman Roads. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

- Childe, V. Gordon. Man Makes Himself. London: Watts & Co., 1936.

- ———. What Happened in History. London: Penguin Books, 1942.

- Cline, Eric H. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Drews, Robert. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Duncan-Jones, Richard. Money and Government in the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Finley, Moses I. The Ancient Economy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

- Frontinus. De aquaeductu urbis Romae. Translated by R. H. Rodgers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Hanson, Victor Davis. The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Book 8.

- Howgego, Christopher. Ancient History from Coins. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Hudson, Michael, and Cornelia Wunsch, eds. Creating Economic Order: Record-Keeping, Standardization, and the Development of Accounting in the Ancient Near East. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2004.

- Knapp, A. Bernard. The Archaeology of Cyprus: From Earliest Prehistory through the Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Kolb, Anne. Transport and Communication in the Roman State. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2000.

- Krentz, Peter. The Battle of Marathon. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Liverani, Mario. The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Mann, Michael. The Sources of Social Power. Vol. 1, A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC–AD 337). Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos, ed. Ancient Egyptian Administration. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Morris, Ian. War! What Is It Good For? Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

- ———. Why the West Rules—for Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010.

- Schaps, David. The Invention of Coinage and the Monetization of Ancient Greece. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004.

- Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. How Writing Came About. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996.

- Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Sidnell, Philip. Warhorse: Cavalry in Ancient Warfare. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006.

- Snodgrass, Anthony M. Arms and Armour of the Greeks. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967.

- Trigger, Bruce. Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Waldbaum, Jane C. “From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean.” Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology LIV (1978): 106-120.

- Ward-Perkins, Bryan. The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Whitby, Michael. “The Army and Defense.” In The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 14, 401–405. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.